From Warehouse Floors to Global Dancefloors: The Start of Chicago House

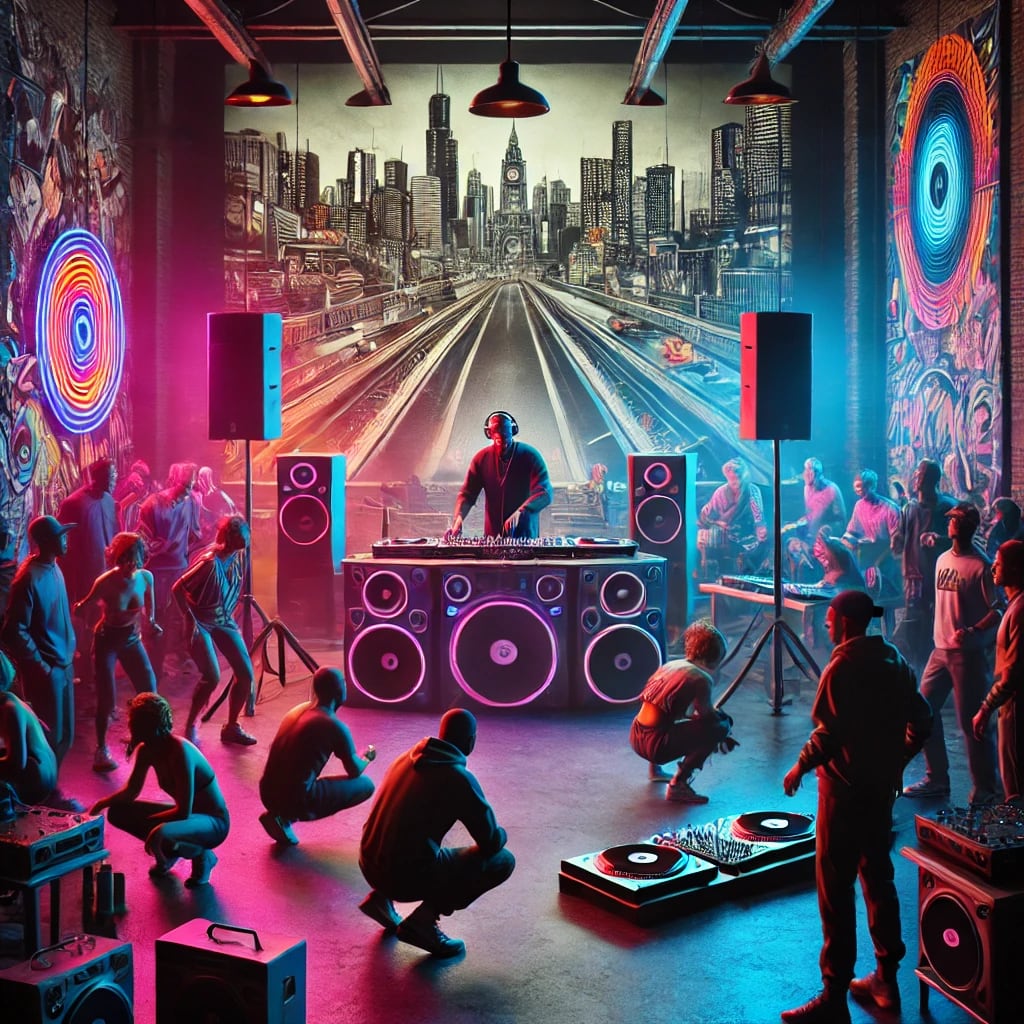

Born in 1980s urban nightlife, Chicago House blended disco’s groove with electronic beats. Pioneered by DJs like Frankie Knuckles, this style sparked worldwide dance revolutions, reshaping club culture, sound, and creative expression.

Rhythms Out of the Shadows: Chicago’s Dancefloor Revolution

The Urban Landscape: Roots in a Changing City

To understand Chicago House, it’s essential to begin with the restless energy of Chicago in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The city pulsed with cultural diversity, but also faced pronounced economic decline, high unemployment, and sharp racial segregation. Many neighborhoods were left with abandoned warehouses and shuttered factories. Out of these spaces, a new musical community began to gather, seeking joy and connection amidst the city’s challenges.

For Chicago’s Black and Latino LGBTQ+ communities, mainstream clubs were often unwelcoming—if not outright hostile. In response, these groups created their own safe havens. The most legendary of these was The Warehouse, a converted space on the city’s near west side. Here, dancers and dreamers met each weekend, forging a nightlife culture that would transform the world of music. The club’s influence would extend far beyond its walls, ultimately lending the music its name: house.

Disco’s Twilight and the Spark of Innovation

The dawn of Chicago House is inseparable from the final, fading days of disco. The so-called “Disco Demolition Night” in 1979 at Comiskey Park marked a violent backlash. Records were destroyed in front of massive crowds, and the popular mood soured against what many saw as artificial and over-commercialized music. Yet for many in marginalized urban neighborhoods, disco remained a vital force.

Out of this tension, DJs in Chicago kept disco’s heartbeat alive but began searching for new forms. Traditional live bands and orchestras became less accessible due to shrinking club budgets. In their place, electronic instruments like the Roland TR-808 and later the TR-909 drum machines offered a cheaper, more versatile way to create throbbing dance rhythms.

As DJs began to experiment with these tools, new possibilities opened up. Drum machines, synthesizers, and samplers allowed for endless combinations and manipulation of sounds. These early adopters weren’t just spinning records—they were live remixing, stretching songs, layering beats, and inventing a new grammar for dance music. The sound was leaner, faster, and rougher than the slick productions coming from New York or Philadelphia.

The Pioneers: Visionaries Behind the Decks

Frankie Knuckles, often called the “Godfather of House,” played a pivotal role at The Warehouse. His sets were legendary for their journey-like construction, mixing soulful disco, European electro, and early hip-hop. He would tweak songs on the fly, using reel-to-reel tape recorders and effects to reimagine familiar tracks. Knuckles wasn’t alone—other essential figures, such as Ron Hardy at the Music Box and Farley “Jackmaster” Funk, brought their own bold visions. Each of these artists shaped house in unique ways.

Ron Hardy’s style was raw and unfiltered. He played tracks faster than their original speed, infused even more experimental elements, and pushed sound systems to their limits. His crowds didn’t just dance—they surrendered to hypnotic rhythms for hours. Hardy’s willingness to break rules and ignore conventions attracted a fiercely loyal audience. Meanwhile, DJs like Jesse Saunders took things a step further: instead of only playing other people’s music, Saunders and contemporaries like Chip E. began making their own house records. On and On by Jesse Saunders, released in 1984, is widely recognized as the first officially pressed house music single.

Technology Changes Everything: The DIY Revolution

A central part of Chicago house’s rise was its embrace of new, affordable music technology. Equipment like the Roland TR-808 and TB-303 bass synth had been marketed to amateur bands, but failed to gain traction in mainstream rock. They soon found a second life in back rooms and bedrooms across Chicago.

These tools allowed anyone with determination and a small budget to create club-ready tracks. Producers began recording basic drum loops, looping bass lines, and layering in melodic hooks. There was little emphasis on polish; what counted was energy and groove. Tracks were often assembled on the fly, pressed onto acetate records called dubplates, and tested in real time on dancefloors.

This “do-it-yourself” approach also democratized music production. Instead of huge studios and expensive sessions, it was now possible for teenagers with a borrowed drum machine to produce the next underground hit. Small labels like Trax Records and DJ International emerged, run by enterprising club kids and DJs themselves. They pressed thousands of records, many of them hand-stamped or in unmarked sleeves, fueling a culture that thrived on discovery and innovation.

Sound System Culture and the Art of the Mix

Another key piece of the movement was the evolving role of the DJ. Mixing became not just a technical skill but a form of musical storytelling. DJs stitched together extended edits, blended drum breaks, and used effects like echo and reverb to create immersive sonic environments. House music’s simple 4/4 beat—the steady pulse underneath the music—became the perfect foundation for these creative experiments.

Sound systems grew ever more complex, as clubs invested in bigger speakers and customized lighting. The dancefloor wasn’t just a space for entertainment; it became a laboratory where music was put to the test, tweaked, and reimagined each night. Listeners became collaborators, sending feedback through movement and energy. DJ sets grew into communal rituals, with cheers erupting for new or unexpected tracks.

Beyond Chicago: Wider Influence and International Impact

By the mid-1980s, the house sound could not be confined to one city. Records pressed in Chicago reached beyond local nightclubs and spread through tape trading, record shops, and radio shows. Importantly, British DJs and music fans, always on the hunt for cutting-edge sounds, began importing Chicago house records. Songs like Move Your Body by Marshall Jefferson and Can You Feel It by Larry Heard found devoted audiences in London, Manchester, and beyond.

At the same time, New York’s club scene was taking note. Chicago house influenced legendary nightspots like the Paradise Garage and became a backbone in the development of future genres such as deep house and acid house. These transatlantic exchanges helped solidify house music’s reputation as a truly global phenomenon. In cities as far-flung as Berlin, Johannesburg, and Tokyo, local artists would soon begin shaping the music to fit their own stories and communities.

Lasting Legacy: House Becomes Culture

Chicago house was more than a musical trend—it was an answer to exclusion, a tool for connection, and a declaration of creative independence. At its core, it told the story of marginalized communities who claimed joy on their own terms, using whatever tools and spaces they could find.

Today, traces of those early days linger in every house beat, each DJ mix, and every crowded dancefloor across the world. The sound continues to evolve, inspiring new generations of artists. As technology advances, the spirit of experimentation at the heart of Chicago house remains undimmed, constantly forging new paths in global music culture.

Machines and Magic: The Sound Shape of Chicago House

From Soulful Foundations to Mechanical Innovation

The heartbeat of Chicago House is its distinct blend of human emotion and machine precision. At its core, this genre breathes new life into the soulful foundation of disco, yet it radically reshapes that heritage through the lens of technological experimentation. While disco offered lush arrangements and orchestrated grooves, house music stripped these sounds to their essence—focusing on rhythm, reinterpretation, and raw energy.

One of the most defining features of early house is the relentless, hypnotic four-on-the-floor beat. In every bar, a bass drum pulse lands on each beat—a simple concept, but one that became the basis for a global dance movement. Unlike the more complex drum patterns of funk or soul, this steady kick provided a blank canvas, inviting both dancer and DJ to lose themselves in its repetition. Frankie Knuckles, celebrated as the “Godfather of House,” used this rhythmic bedrock to glue entire nights together, merging tracks seamlessly in marathon DJ sets.

The transformation wasn’t just in the beats. As the music evolved inside Chicago’s makeshift clubs, creativity was often driven by the limitations—and possibilities—of early electronic gear. Producers used drum machines like the Roland TR-808 and TR-909 to create punchy, robotic percussion, unmatched by live drummers for consistency and power. This gave house tracks their unmistakable snap and forward momentum. Classic house also leaned heavily on the Roland TB-303 bass synthesizer, which, though designed to mimic electric bass guitar, produced a squelching, undulating sound that became iconic in later styles but was already being explored alongside soulful elements in Chicago.

These sounds marked a departure from traditional instrumentation, but they also allowed for new kinds of emotional expression. Sliding between mechanical and deeply human, house was never afraid to layer in warm, gospel-inspired vocal lines, echoing the communal roots of Black church music. In tracks like Your Love by Frankie Knuckles and Jamie Principle, machine beats coexist with expressive, yearning vocals—a sound that feels both futuristic and familiar, echoing on packed dancefloors and in solitary late-night listening.

The Power of Repetition: Loops, Samples, and the Art of the Remix

A key ingredient in Chicago House is the use of loops and samples—a detail that distinguishes it from its disco predecessor. DJs and early producers often relied on dual turntables and reel-to-reel tape machines to shape long, trance-inducing grooves. By looping short sections of older songs—maybe a snare hit, a horn riff, or a vocal phrase—they created entirely new sonic landscapes. These repeating patterns built momentum, inviting dancers into an almost meditative state.

Where disco producers might use entire orchestras to craft a sense of drama, house architects like Jesse Saunders and Chip E. focused on minimal elements, weaving snippets of soul and funk into a cycle of excitement and anticipation. For instance, On and On by Jesse Saunders employs a simple vocal phrase and a chugging bassline, layered with crisp hi-hats and snare hits. The result isn’t cluttered, but it pulls listeners in through subtle variation and precise layering.

Sampling also served a deeper purpose—it became a way for marginalized communities to reclaim cultural memory. By lifting gospel vocals or funk riffs from records that had been overlooked or devalued, Chicago’s house producers created bridges across eras and generations. Each track became an act of discovery, with DJs using old sounds to speak to present-day struggles and dreams. This loop-based approach laid the groundwork for the entire modern remix culture, as house producers began to manipulate not only existing songs but their own tracks in real time, transforming each mix into an evolving work of art.

Technology’s Role: DIY Spirit and Studio Experimentation

In Chicago, creativity often grew out of scarcity. With little access to professional studios, many house pioneers assembled homemade rigs from pawn shop finds and borrowed gear. Drum machines and simple sequencers let anyone with patience and a sense of rhythm build tracks layer by layer. This resourcefulness shaped the lo-fi, gritty character of early house—the hiss of tape, the crackle of vinyl, all became part of the music’s underground allure.

Limited means rarely limited ambition. Techniques like “trackier,” less song-based mixes—focused on rhythm, bass, and percussive details—emerged. These works left behind traditional “verse and chorus” structure, instead moving forward in hypnotic, evolving waves. Producers like Larry Heard (aka Mr. Fingers) embraced this with masterpieces like Can You Feel It, blending lush, ethereal chords and simple basslines into a smooth, atmospheric flow.

Effect processing played a key role, too. Reverb, delay, and other electronic effects became vital not for hiding mistakes, but for crafting specific moods. Echoes and washes could make a vocal seem to float above the beat, or turn a snare drum into a sudden burst of sonic energy. These elements weren’t just technical tricks—they allowed artists to move listeners through different emotional spaces as the night progressed.

House as Community: Audience, Emotion, and Social Connection

The structure of Chicago House reflected the needs of its dancers—mostly young, working-class Black and Latino LGBTQ+ people seeking escape and affirmation. The extended, groove-based format let dancers find their own space and time within the music. Songs were rarely about fast hooks or radio-friendly length. Instead, tracks stretched out, often past the six-minute mark, encouraging deeper musical journeys.

Dancers themselves shaped the music’s direction. DJs would stretch or re-shape the energy to match the feel of the crowd. If the atmosphere was euphoric, records with soaring vocal peaks dominated. When things cooled down, deeper, “jackin’” tracks with relentless basslines and subtle changes kept feet moving while allowing for introspection. The term “jacking”—slang for the undulating, body-centered dance style—became part of the genre’s DNA. Songs like Jack Your Body by Steve “Silk” Hurley captured this sense of physical and communal release.

Chicago House’s emotional range set it apart from both disco’s drama and the colder, more mechanical side of later electronic music. Gospel-influenced vocals brought uplift and vulnerability; tracky instrumentals provided space for catharsis and release. In houses and warehouses across the city, the music fostered a sense of belonging, adventure, and hope.

A Living Legacy: Blueprint for Future Sounds

Chicago House didn’t just invent a new set of musical tools—it changed the way music was experienced on and off the dancefloor. Its minimalist yet emotionally potent style inspired entire generations of artists worldwide. British and European producers absorbed the structure and spirit of house, giving birth to genres like acid house and deep house. Even today, traces of Chicago’s innovations can be heard everywhere: in pop anthems, tech-house DJ sets, and the sound design of video games and commercials.

The story of Chicago House is a testament to the powerful interplay between people, technology, and place. Its musical characteristics emerged not just from creative inspiration, but from the practical realities and vibrant communities of a changing city—a legacy that continues to reinvent itself wherever people gather to dance.

Beyond the Beat: How Chicago House Splintered and Spread

Jacking, Acid, and Deep Feelings: The Pulse of Early House Evolves

Step inside a Chicago club in the mid-1980s and every night felt just a bit different. As the heartbeat of Chicago House grew louder, the genre quickly divided into several offshoots, each shaped by unique neighborhoods, new technology, and the restless creativity of local DJs. The innovations didn’t stop at steady four-on-the-floor beats—within a few years, a single city map charted a world of musical possibilities.

The first noticeable branches were jacking house, acid house, and deep house. Although all three thrived on the dancefloor, each one cultivated its own mood and crowd. Jacking house emerged directly from the legendary dance move called “the jack”—a wild, body-shaking release that turned club spaces into collective celebrations. Here, music pulsed with muscular energy and crisp rhythms. Producers like Farley “Jackmaster” Funk pushed up the tempo, spinning tracks such as Love Can’t Turn Around that commanded dancers to “jack your body!” These songs often leaned on playful, chopped-up vocal phrases and fast, syncopated handclaps. The style’s rawness reflected the liberated, anything-goes spirit of Chicago’s underground nightlife—a gathering point for those determined to carve out spaces of freedom outside the city’s mainstream.

Another path quickly diverged: acid house. Unlike earlier styles, acid house’s personality revolved around the mysterious, squiggly sounds of the Roland TB-303 bass synthesizer. This small machine had originally been designed as a practice tool for guitarists, but inventive producers in Chicago reimagined it as the voice of a new movement. The TB-303’s signature: rapidly shifting, liquid-like basslines that bubbled and twisted, freakish and almost alien. Phuture, led by DJ Pierre, set the template with the record Acid Tracks in 1987. What began as a local experiment quickly accelerated into a global obsession, inspiring a sea of copycat artists both in the city and across the Atlantic, where acid house took over British club culture almost overnight.

While jacking and acid chased intensity and experimentation, deep house delivered a more soulful antidote. At the center stood Larry Heard (Mr. Fingers), whose production on Can You Feel It and other tracks layered gentle keyboard chords and subtle melodies over the genre’s relentless bass drum. Deep house nurtured a moodier, more introspective flavor, borrowing from jazz harmonies and gospel vocals. This branch of the genre invited listeners to lose themselves not only in rhythm, but also in atmosphere—a sound suited as much for solitary headphone listening as for packed dancefloors.

Mutations in the Machine: Genre Hybrids and New Sounds

What made Chicago’s club scene so special was its openness to endless reinvention. New hybrids popped up as DJs experimented with different influences and outsider sounds. Sometimes, those hybrids ended up becoming musical worlds of their own.

One important crossover was with hip-hop, thanks to the emergence of hip house. In the late 1980s, artists like Fast Eddie and Tyree Cooper began laying rapped vocals over pulsing house instrumentals, bridging the gap between club and street cultures. Tracks like Hip House and Turn Up the Bass demanded new styles of dancing and drew in fans who might otherwise have skipped typical dance music nights. This fusion didn’t just feel fresh; it made it clear that house was more than a genre—it was a living, breathing musical language, able to adapt and speak to new audiences.

Meanwhile, women’s voices were growing more central. Vocal house, sometimes called diva house, leaned heavily on the powerful performances of singers like Jamie Principle. These tracks took gospel’s emotional delivery and set it against synthesized backdrops, creating dramatic peaks and valleys for dancers and listeners alike. This approach not only broadened the music’s appeal but helped to highlight the roots house shared with earlier African American traditions.

Another offshoot worth noting: garage house. Ironically, while the word “garage” refers to New York’s Paradise Garage club, Chicago producers were quick to embrace its elements—especially basslines and organ riffs borrowed from gospel and soul. The sound became warmer, more melodic, and sometimes slower. This exchange between cities revealed how house music, though born in Chicago, was never isolated. There were constant conversations between scenes—through records, radio waves, and midnight phone calls between DJs.

Taking Over the World: Chicago House’s Influence Abroad

Chicago’s musical offspring were not content to stay in their hometown. As records traveled—mainly as white label pressings sent in unmarked sleeves—the unique flavors of Chicago House landed in clubs from Manchester to Berlin. British DJs seized on acid house in particular, launching enormous “warehouse raves” that would help rewrite the rules of European nightlife. The TB-303’s distorted lines became iconic almost overnight. These sounds also arrived in Ibiza, Spain, where they mingled with sunny Balearic beats to form new hybrids that soon swept the continent’s summer festival circuit.

In South Africa, the kwaito movement of the early 1990s took clues from Chicago’s legacy, combining local rhythms and languages with house-style electronics. In Europe, offshoots like French house and techno emerged, with producers such as Daft Punk and Laurent Garnier always referencing Chicago’s blueprint.

It wasn’t just about parties. These exported subgenres subtly helped unite subcultures across borders. Young people in Detroit, London, Tokyo, and Johannesburg all jumped to similar rhythms, bringing house music fully into the hands of a new generation.

The Return Home: House Revivals and Modern Twists

Even as Chicago House influenced hundreds of directions abroad, the genre never truly left its hometown. Instead, it shape-shifted with every decade. In the 1990s, classic elements resurfaced with ghetto house, spearheaded by labels like Dance Mania and producers like DJ Deeon and DJ Funk. Ghetto house was all about stripped-down, hyper-energetic tracks using simple drum patterns and risqué lyrics, designed for fast footwork and late-night dance battles on the city’s South and West Sides.

By the 2000s, a new generation was ready to reinterpret the genre again. Footwork and juke pushed tempos even higher and broke traditional rhythmic structure, challenging dancers to keep up. This fresh evolution once again showed that house music’s roots run deep but never stay fixed.

If you listen closely to global pop hits, festival anthems, or even background music in your favorite cafe, echoes of Chicago House persist. The open spirit of collaboration, experimentation, and cultural exchange remains at the heart of every new twist. Beneath every thundering bass drum or swirling synth line, the genre’s original invitation endures—an open call to lose yourself, build something new, and keep the dancefloor alive.

Dancefloor Architects: The Visionaries and Anthems Behind Chicago House

The Warehouse Wizards: Frankie Knuckles and the Birth of a Movement

No story of Chicago House truly begins without Frankie Knuckles, whose legendary sets at The Warehouse rewrote the rules of nightlife and sound. Known among fans as the “Godfather of House,” Knuckles became the pulse of Chicago’s underground from the late 1970s. Equipped with a deep knowledge of disco, soul, and R&B, he was among the first DJs to envision these genres through the prism of new technology.

But Knuckles wasn’t just about mixing records—he pioneered creative techniques that made every party feel like a journey. Using twin turntables, reel-to-reel tape edits, and a rotating arsenal of drum machines, he layered beats and vocals, building songs into hypnotic marathons that kept clubbers moving deep into the night. What truly set him apart was his understanding of mood: his sets combined infectious energy with uplifting emotion, offering both liberation and belonging to a crowd who craved escape from mainstream discrimination.

His early masterpiece, Your Love (produced with Jamie Principle in 1984 and released in 1986), embodies this ethos. The track’s slow-building synthesizer lines, pulsing bass, and soulful vocals stand as the emotional blueprint for the genre. Your Love wasn’t just a dance anthem—it was a signal to misfits and outsiders that they had a home on the floors of Chicago. This record, still remixed and revered worldwide, reveals how Knuckles shaped not only the sound but also the spirit of house music itself.

A City of Producers: Marshall Jefferson and the Deep House Revolution

As Chicago’s scene swelled, new producers emerged, eager to push boundaries further. Marshall Jefferson, often called the “father of deep house,” carved his own lane with the 1986 track Move Your Body (The House Music Anthem). While many hits of the era stuck to bare-bones machine rhythms, Jefferson’s definitive song introduced rich piano chords and gospel-style vocals—elements then considered foreign in electronic dance music.

Move Your Body took house in a sharply different direction. The piano riff became instantly recognizable, infusing each club room with warmth and feeling, while the impassioned vocals transformed impersonal warehouse parties into moments of collective celebration. Jefferson showed that house music could wear its optimism on its sleeve: while built on machinery, the sound could still carry a distinctly human touch.

Furthermore, Jefferson’s approach inspired a generation of producers—locally and globally—to experiment with melody, harmony, and real instruments. The DNA of deep house, from London to Johannesburg, traces back to his innovative direction. Tracks such as Open Our Eyes and his work for Ten City pushed the genre towards emotional storytelling, forever expanding the limits of what a dance track could evoke.

Jackmasters and Hitmakers: Farley, Jesse Saunders, and the Pop Crossover

While deep house spread warmth, other pioneers made house music grittier and more direct. Farley “Jackmaster” Funk blazed through Chicago’s clubs, championing a rowdier energy. His most famous release, Love Can’t Turn Around (1986), transformed the scene. Co-produced with Jesse Saunders and featuring the dramatic vocals of Daryl Pandy, the song blended relentless, jacking beats with catchy hooks.

This wasn’t just club fare—it was history in the making. When Love Can’t Turn Around climbed the UK charts, house music leaped from Chicago basements to international airplay. Suddenly, this underground sound commanded attention in Europe, opening doors for countless artists.

Saunders himself holds a special place in house mythology for releasing On and On in 1984, widely credited as the first ever house record pressed on vinyl. Relying on simple drum machines, a borrowed bassline, and a repeating synth riff, On and On defined early house’s raw, DIY character. The track quickly became a staple for DJs—its looping pattern irresistible for extended dancefloor workouts. Saunders’s contribution proves how Chicago house’s early days were shaped as much by necessity as by genius: studio time was scarce, but imagination was boundless.

Acid Architects: Phuture and the Power of the 303

Chicago’s inventive spirit reached a new level with the rise of acid house—a subgenre that pushed the available technology to its limits. At the movement’s core was Phuture, a trio featuring DJ Pierre, Spanky (Earl Smith), and Herb J. Their 1987 track Acid Tracks changed everything. Using the Roland TB-303 “bassline” synthesizer, they manipulated the machine into delivering a squelching, unpredictable melody utterly unlike anything heard before.

For many, Acid Tracks was more than a song—it was a revelation. The 303’s slippery, undulating patterns became acid house’s defining texture, influencing not just Chicago, but raves across the US and soon, Europe. DJs first tested the track in Chicago’s Music Box, gauging the dancefloor’s astonished reactions before releasing it to the public. The sound’s futuristic edge, born from creative misuse of a single machine, proved irresistible to a generation craving new sensations.

The acid house movement signaled how rapidly house music evolved. Thanks to Phuture and their peers, what began as a soulful groove became a launchpad for sonic experimenters everywhere.

Voices of Change: Women, Vocalists, and the Choir Spirit

While house’s biggest producers often captured the headlines, vocalists played a vital role in shaping the genre’s emotional landscape. Jamie Principle—whose falsetto adorned Your Love and Baby Wants to Ride—gave house its haunting edge. However, behind countless Chicago house classics were passionate, technically gifted singers bringing depth and range to every performance.

Byron Stingily, with his vibrant tenor on Ten City’s soaring tracks like Devotion, brought gospel power to crowded dancefloors. Meanwhile, female singers such as Liz Torres and Kym Mazelle injected energy and soul into hits like Can’t Get Enough and Taste My Love. Often, these voices channeled themes of resilience, romance, and freedom, connecting directly with clubgoers seeking not just escape, but affirmation.

Moreover, the presence of gospel choirs on tracks by Marshall Jefferson and Farley Jackmaster Funk reminded listeners of house music’s communal origins. Their contributions forged powerful moments of unity—choruses rising above the synthesizers and drum machines, echoing struggles and hopes of Chicago’s marginalized communities.

Global Echoes: The Legacy of Chicago’s Sound

By the late 1980s, the influence of these key figures and works could not be contained within Chicago’s boundaries. House records found eager audiences in London, Manchester, and Paris, seeding entirely new scenes. British clubs imported Move Your Body and Love Can’t Turn Around, sparking a rise in local house and the early rave movement.

Furthermore, the production methods refined by Knuckles, Jefferson, and Saunders—emphasizing affordable drum machines, home recording, and crowd-led feedback loops—democratized access to music-making for young creatives everywhere. Their ethos resonated worldwide: with minimal resources, anyone could build the next dancefloor anthem from a bedroom or basement studio.

Chicago house’s influence moves through every corner of global electronic music today, as producers sample, reference, and reinterpret those first legendary records. What began in a handful of clubs and studios now ripples through stadiums and digital playlists, carried by the vision and ingenuity of Chicago’s original house architects.

Rhythm Boxes and Raw Grooves: The Secret Science of Chicago House

The Drum Machine Revolution: Powering the House Pulse

At the heart of Chicago House lies a love affair with drum machines. In the early 1980s, producers on Chicago’s South and West Sides were driven as much by curiosity as by necessity. Vintage disco bands needed strings, brass, and large studios—not to mention significant budgets. Amateur house creators, in sharp contrast, often had little more than a few savings, a cramped bedroom, and towering piles of vinyl. But what they did have, crucially, were drum machines, above all the now-legendary Roland TR-808 and Roland TR-909.

These devices opened new possibilities. While earlier rhythm boxes could only simulate the sound of a basic drummer, the TR-808 and TR-909 allowed users to tweak, sculpt, and manipulate patterns in real time. The deep, punchy bass of the 808 quickly became a house signature, providing a thick sonic bed that felt equally at home in a sweaty club or a car stereo. The TR-909 added crisp snare hits, sharp hi-hats, and the programmable ability to create evolving, mesmerizing patterns. Unlike the organic fluidity of a live drummer, these machines offered relentless consistency—an attribute that fueled the hypnotic, steady pulse that defines classic house tracks.

Moreover, these devices were accessible. The TR-808 and TR-909 were initially marketed as affordable alternatives to studio session musicians. In Chicago, resourceful teens and aspiring DJs snapped up used units at pawn shops or bought them off friends. This affordability played a decisive role in bridging the gap between professional studios and grassroots creativity.

Sampling and Sequencing: Building a New Sonic Collage

Advancing beyond basic beats, Chicago House producers became masters at slicing and reworking sound. Two key technologies drove this innovation: the art of sampling and the use of sequencers. Early samplers—like the E-mu Emulator or the Ensoniq Mirage—let producers grab tiny slices of music (a snatch of a disco record, a soulful vocal shout, or even an everyday street sound) and turn them into playable instruments. These short, repetitive “samples” became loops that could be layered, pitched, or filtered, creating depth and variety from minimal resources.

Sequencers, both hardware-based and later in software, let producers string these samples and machine rhythms together into full, hypnotic arrangements. Finished tracks might run for six, eight, or even ten minutes, each gradually evolving as small elements—an extra handclap, a new synth line, a filtered vocal—entered or departed. This linear, unfolding structure catered perfectly to long DJ sets, allowing seamless blending and constant motion on the dancefloor.

This approach, technically straightforward yet creatively unlimited, empowered producers to express both homage and rebellion. By directly sampling disco hits, gospel choirs, or funk breaks, they kept Black musical heritage alive—but the way these sounds were spliced and reimagined placed them firmly in the future.

Synths and Atmosphere: The Emotional DNA of House

While rhythm machines gave Chicago House its firm backbone, synthesizers provided its color and soul. Even with limited budgets, producers found that minimal gear could deliver vast results. Instruments like the Roland Juno-106 or Yamaha DX7 became workhorses, prized for their lush pads, infectious basslines, and the warmth that smoothed the genre’s mechanical edge.

These keyboard-driven textures weren’t just window dressing. Synth stabs and shimmering chords sculpted the genre’s emotional landscape. In tracks like Frankie Knuckles’ Your Love or Marshall Jefferson’s Move Your Body, ethereal synth washes build a sense of uplift and longing. Tight, melodic basslines, often programmed on the same instruments or with a Roland TB-303 (later key to acid house), keep energy rising without ever feeling cluttered.

This economical use of gear meant every note carried weight. Unlike earlier styles that layered full orchestras or vast bands, House thrived in the space between sounds. Small, repeated motifs—one-note riffs, airy chords, clipped vocal phrases—became hypnotic through their repetition, echoing the endless possibility of the dancefloor itself.

DIY Studios and the Art of Imperfection

Technical limitations often forced producers to invent their own recording and mixing techniques. Makeshift studios, sometimes no more than a basement corner or a friend’s living room, became creative havens. Affordable multi-track cassette recorders like the Tascam Portastudio or budget mixers allowed artists to experiment with multi-layered arrangements on a shoestring.

Mistakes and accidents weren’t erased—they were embraced. A clashing tape splice, distorted drum sound, or mismatched vocal became part of the house aesthetic. The raw edges were celebrated, not hidden, signaling an authenticity that stuck with fans. In many cases, a rough-and-ready mix lent tracks a gritty, urgent sound that perfectly reflected the energy of late-night parties and the vibrant, sometimes chaotic life of Chicago’s underground.

Moreover, the immediacy of this DIY approach fit the scene’s ethos. Tracks could be produced, cut to acetate, and played in a club within days—meaning feedback came straight from the dancefloor. What worked survived and was copied; what flopped disappeared, leaving almost no record. This constant trial and error fueled relentless innovation.

DJ Techniques: Melding Tracks, Sparking Action

Another cornerstone of Chicago House’s technical identity was the art of DJing. Unlike prior disco or soul sets—where songs often played from start to finish—house DJs used two (or more) turntables to blend, extend, and reshape music live. Tools like the Technics SL-1200 turntable and Numark or Vestax mixers enabled precise beat-matching. DJs beat-synced records, using crossfaders and EQ knobs to accentuate or suppress elements and create long, tension-building transitions.

Edits and “re-edits” became common. Early house DJs would splice tape, add drum machines to old soul records, or even incorporate live mixing tricks. This spirit of experimentation made the entire DJ set into a performance, turning club nights into journeys that blurred the line between pre-recorded music and real-time creation.

The open-ended, participatory nature of the genre created space for new voices and ideas, both on the decks and in the studio. The DJ’s booth became a laboratory, constantly reinventing the sound and experience of house.

Legacy of Innovation: The Global Blueprint

The technical language developed in Chicago’s house scene didn’t just stay local—it spread worldwide. Musicians in New York, London, Berlin, and far beyond borrowed these tools, reshaping local scenes with drum machines, sequenced synths, and sample-based production. The hands-on, flexible, and sometimes chaotic approach to craft became a blueprint for dance music globally.

As technology evolved—shifting from tape recorders and hardware to software suites like Ableton Live or FL Studio in the 21st century—the core principles remained. Simplicity married to spontaneity, a devotion to rhythm, and a willingness to celebrate imperfection continue to define the heart of dance music.

In this way, the technical wizardry of Chicago House has proven timeless—even as the gear and the world around it continue to transform.

From Warehouse Underground to Global Anthem: How Chicago House Changed Culture

Club Sanctuaries: New Spaces for Freedom and Identity

When the pulse of Chicago House first vibrated through the speakers of clubs like The Warehouse and Music Box in the early 1980s, it was more than just a new style of music. The dancefloor became an urgent answer to social exclusion, giving birth to spaces where self-expression did not only survive, but flourished. These club nights drew together outcasts, dreamers, and visionaries—especially young, Black, Latinx, and LGBTQ+ Chicagoans who were all too often marginalized by mainstream society.

Stepping into a house club was to experience a unique freedom. The pounding four-on-the-floor beat wiped away hierarchies, and dancers lost themselves beneath swirling lights as DJs like Frankie Knuckles and Ron Hardy spun sets crafted with contagious optimism and communal warmth. In an era scarred by homophobia and racial tensions, these clubs offered rare environments of acceptance and safety. Unlike the restrictive velvet ropes of disco-era hotspots, the venues at the heart of Chicago’s house scene prioritized openness and diversity over celebrity or wealth.

Within this environment, Chicago House took on a role that was equal parts celebration and resistance. For many, these nights meant liberation from harsh realities outside club walls. Here, new identities could be explored, and collective belonging transcended everyday prejudice. The ethos of “Everybody’s welcome” wasn’t just a slogan—it was a lifeline, and the club became home for a generation hungry for connection and recognition.

Community and DIY Spirit: The House Scene as a Movement

Beyond the dancefloor, the rise of Chicago House transformed how people made and shared music. The movement was rooted in grassroots creativity. Home studios, often assembled from cheap gear and secondhand drum machines, let aspiring producers and DJs bypass traditional gatekeepers. Instead of needing record label connections or expensive studios, anyone could cut a house track in their basement. Pressing plants like Precision Records allowed local artists to produce limited vinyl runs, which quickly circulated among DJs and within neighborhood record stores.

This democratization of music reflected a new kind of community economics. Support networks formed around clubs, labels, and local shops. Flyers circulated by hand, radio shows on stations like WBMX gave artists their first real breaks, and collectives sprung up to pool resources. This do-it-yourself approach fostered rapid innovation and a collaborative spirit. When one local DJ made a breakthrough with a reworked drum pattern or vocal sample, others would pick it up, mutating and evolving the sound. The genre felt like a family project, not a corporate invention.

Moreover, characters like Chip E. and Steve “Silk” Hurley embodied that independent attitude. Chip E.’s Time to Jack and Hurley’s Jack Your Body weren’t just club hits; they symbolized the possibility that anyone, with enough determination, could shape a new chapter in music. The empowerment at the heart of house was infectious—its unwritten motto: “If you wanna hear it, make it.” For many Chicagoans, this philosophy extended beyond music, nurturing a can-do approach to community, art, and life itself.

Rewiring the World’s Dancefloors: International Impact and Adaptation

The boundary-breaking energy of Chicago House did not stay put for long. By the mid-to-late 1980s, imported records and DJ mixes began circulating through clubs in New York, Detroit, and soon after, across the Atlantic in places like London, Manchester, and Berlin. What started as a distinctly local movement in Chicago soon became the DNA for a whole new era of dance music worldwide.

European DJs and clubbers, starved for fresh sounds, seized on Chicago’s raw, jacking rhythms and soulful energy. Cult labels like Trax Records and DJ International became musical exporters, ensuring tracks such as Move Your Body by Marshall Jefferson and Acid Tracks by Phuture were heard well beyond Illinois. The British acid house movement, in particular, drew direct inspiration from Chicago’s squelchy, TB-303-powered grooves—sparking dizzying scenes that filled warehouses and fields with euphoric crowds. London’s Shoom club and Manchester’s Hacienda stood as evidence of Chicago’s outsized influence, even as each city adapted the sound with its own twist.

Meanwhile, artists in Detroit borrowed house’s hypnotic repetition and pushed it towards the colder, sleeker mechanics of what would become techno. Across the globe, the collaborative and DIY blueprint set by Chicago’s early house community inspired a wave of independent labels and bedroom producers. In this way, tiny South Side studios and after-hours recording sessions planted seeds that blossomed in distant cities and new genres, forever altering the international map of popular music.

House as Political Voice: Protest, Pride, and Power

At its core, Chicago House stood for more than just music—it became a tool for protest and affirmation. With lyrics emphasizing joy, unity, and resilience, tracks like Frankie Knuckles’ Your Love or Adonis’ No Way Back offered hope in a world that was often threatening. These songs turned the dancefloor into a site of struggle and transformation. The music’s repetitive chants of “jack your body” or “let’s all chant” invited listeners to shed burdens and find strength together.

During the HIV/AIDS crisis, which hit Chicago’s queer communities particularly hard in the 1980s, house clubs served as sanctuaries where people mourned, supported each other, and organized for change. The music became an outlet for grief—but also for boundless resilience. Benefit parties and anthemic tracks raised awareness, funneled resources into advocacy, and honored those lost to the epidemic. The emotional mix of release and defiance—that sense of hope against the odds—remains woven into the DNA of classic house.

Furthermore, house’s appeal to marginalized communities made it a soundtrack for wider battles against discrimination. The emphasis on togetherness resonated far beyond club walls. Later generations adopted house music as anthems for pride parades, political demonstrations, and protest movements, using its insistent beat as both rallying cry and affirmation of identity. In this way, Chicago’s house tradition evolved into a global symbol of solidarity and resistance.

From Underground Trend to Mainstream Influence

The journey of Chicago House from niche club sound to cultural touchstone is a story of persistent impact. By the early 1990s, the house sound had entered the charts—not just in the U.S. and UK, but around the world. Artists like CeCe Peniston, Ten City, and Inner City found mainstream success crafting songs filled with the genre’s lush chords and uplifting energy. Elements of house were soon everywhere—from advertising jingles to blockbuster movie soundtracks, from runway fashion shows to Olympic ceremonies.

Mainstream pop and R&B acts began hiring Chicago producers to inject their records with authentic house grooves. Collaboration between genres created new hybrids—hip house, garage house, and more—further spreading the style’s influence. The house aesthetic—its love of repetition, celebration of the beat, and focus on communal joy—became deeply embedded in the DNA of modern music.

Yet, for longtime fans and originators, the greatest legacy of Chicago’s house revolution is intangible. It’s found in the way the genre continues to inspire new generations to dance, create, and dream. At its heart, house music remains a living tradition—a powerful reminder that sometimes, the most lasting social change begins simply with an irresistible rhythm and an open dancefloor.

Beyond the Turntables: Nightlife Rituals and the Spirit of Chicago House

The Club as Sanctuary: A New Kind of Performance Space

On a sticky summer night in 1980s Chicago, entering a club like The Warehouse, Music Box, or the Power Plant meant stepping into more than just a darkened room with loud music. It was an immersion into a living, breathing culture where every movement—on stage, in the DJ booth, and across the dancefloor—helped forge the story of Chicago House. Unlike the glossy, spectator-driven concerts of rock or pop acts, house events dissolved the classic boundaries between artist and audience. The focus shifted from the solo performer in a spotlight to a kind of collective ritual. Dancers, DJs, and organizers together created an experience that felt both personal and bigger than any individual.

Within these clubs, performance became an exchange rather than a presentation. Frankie Knuckles, for example, was not a distant star above the crowd but a conductor for shared emotions. His sets relied less on technical showmanship and more on reading the energy of the room, building tension with drawn-out mixes and erupting into explosions of joy with just the right drop. The audience, responding in kind, cheered, whistled, and transformed even tiny sonic changes into communal celebrations. This participatory dynamic was fundamental: everyone was a part of the performance, their bodies translating the relentless four-on-the-floor kick into movement, sweat, and release.

Moreover, these spaces nurtured non-traditional artists and creative expressions. Drag performers, vogue dancers, and performance poets found a welcoming stage. The club was a living gallery, a laboratory, and a safe zone where new voices could experiment with gender, identity, and style. This spirit of open collaboration would become a foundational trait of house performance culture, later echoed worldwide.

Techniques of the Night: The DJ’s Artistic Arsenal in Action

To understand the live culture of Chicago House, it’s essential to consider not only the music played, but the methods of its delivery. The late-night DJ sessions at focal venues like The Warehouse and Music Box weren’t just routine nights out; they were rituals shaped by technology and technique.

DJs wielded vinyl records, drum machines, samplers, and mixers with almost sculptural intent. Early on, nights unfolded with long blends, where two tracks glided into each other seamlessly, the lines between songs dissolving. The now-revered “edit” culture took hold, with local DJs like Ron Hardy and Steve “Silk” Hurley reworking tracks live, stretching instrumental sections and manipulating vocal snippets. Reel-to-reel tape decks provided the means to loop or extend key passages, moving beyond what was printed on commercially available records.

In the live context, these technical choices were far from academic. For the audience, spontaneous re-edits or a bass drum suddenly “pushed forward” in the mix could ignite the floor. The interplay between DJ intuition and audience feedback gave performances a unique, organic character. House culture’s obsession with the remix—not just in recordings but as an approach to live performance—meant every night offered something unrepeatable.

This hands-on manipulation wasn’t limited to the DJ booth. Dancers, sometimes organized into impromptu crews or “houses,” contributed their own artistry. Styled after family structures, these groups added competitive dance battles, voguing, and elaborate costumes to the spectacle, further blurring the lines between observer and participant.

Tradition Meets Evolution: Residencies and the Rise of the Superstar DJ

One unique feature of Chicago House performance culture was the centrality of DJ residencies—regular spots held by beloved selectors who shaped entire club identities. Unlike touring acts or festival stars, these resident DJs developed deep relationships with their crowds. Week after week, they tuned their sets to the evolving desires of local dancers, rewarding loyalty with carefully introduced new sounds.

Residencies defined both venue and movement. Frankie Knuckles at The Warehouse, Ron Hardy at Music Box, and Lil’ Louis at the Bismarck Pavilion became fixtures not just for their selections but for the specific flavor each brought to the evening. Hardy, for instance, was famous for pushing boundaries—playing records backward, increasing speed to bewildering paces, and breaking genre rules. That unpredictability fostered a listening culture that valued innovation and surprise over nostalgia or mere entertainment.

Over time, this model produced a new kind of music celebrity. The idea of the “superstar DJ”—eventually globalized by dance festivals and superstar tours—was, in many ways, seeded in these gritty Midwestern rooms. Yet in early Chicago, celebrity was still rooted in community: a respected crowd-pleaser was someone who made the dancefloor erupt, not just someone with a hit record. Live performance remained tethered to the energy and needs of the neighborhood, not just the demands of distant promoters or broadcasters.

When Local Energy Fuels Global Movements: House Sound Travels

As the 1980s wore on, the exuberant live culture of Chicago’s house clubs sent ripples far beyond

the city limits. Internationally, visiting DJs and curious producers began to visit, taking home

bootlegs and mixtapes. British clubgoers who experienced house nights in Chicago returned to

London, Manchester, or Ibiza eager to replicate the intensity and inclusivity they had witnessed.

This transatlantic connection helped kickstart the so-called “Second Summer of Love” in the UK and

fed the birth of rave and acid house culture in Europe.

The original Chicago clubs—cramped, friendly, and often improvised—became a kind of blueprint for dance events worldwide. The value placed on community, improvisation, and freedom of movement inspired everything from mega-raves to smaller, community-based parties. Even the ever-present use of iconic drum machine sounds (like the bouncy clap of the TR-808) signaled to dancers everywhere a thread tying them to that original energy.

What grew out of Chicago’s shadows became a global phenomenon, but the performance roots remained unmistakable: music delivered in the moment, for the people in the room, where the act of coming together mattered as much as the songs themselves.

The Enduring Ritual of House: Today’s Echoes of Chicago

Though many legendary venues have since closed and the original pioneers moved on or passed away, the central rituals of Chicago House endure. Today’s house parties—whether in massive clubs in Berlin, small bars in Johannesburg, or open-air festivals in São Paulo—all echo the values first cemented by Chicago’s trailblazing nightlife: inclusion, innovation, and a devotion to the dancefloor as communal gathering space.

Modern DJs continue to honor these past rituals, mixing vinyl with digital controllers, looping live vocals, and inviting spontaneous performances. House nights remain spaces for marginalized voices, queer celebration, and creative self-expression. The boundary between performer and crowd continues to blur as new generations honor the revolutionary spirit of those early Chicago clubs.

And so, even as the face of club culture changes with each decade, the defining energy of Chicago House—that deep sense of togetherness and creative possibility—remains alive at every performance, urging both artists and listeners to keep moving forward.

From Basement Beats to Worldwide Waves: Tracing the Rise and Spread of Chicago House

The Neighborhood Laboratory: Early Innovations and the Sound’s DNA

The initial phase of Chicago House wasn’t marked by major record labels or global radio hits—it began in backroom studios, home kitchens, and makeshift recording spaces scattered across Chicago’s South and West Sides. Driven by ingenuity and limited resources, young producers like Jesse Saunders, Chip E., and Steve “Silk” Hurley fused the hypnotic pulse of drum machines with samples lifted from disco, funk, and soul records. These artists pieced together audio fragments on repurposed turntables and sequencers, pushing the limits of what could be done with basic gear.

Crucially, these early tracks—On and On by Jesse Saunders, Mystery of Love by Larry Heard, and Jack Your Body by Steve “Silk” Hurley—established sonic blueprints that would shape house music’s identity well beyond Chicago’s borders. Most tracks were pressed in tiny runs, sold directly out of record stores, or circulated on cassettes passed hand-to-hand between DJs and dancers.

This underground, grassroots exchange enabled ongoing refinement. Productions grew more adventurous, with tracks stretching into longer instrumental grooves built for the dancefloor rather than radio. As different neighborhoods and clubs experimented with variations, a wide tapestry of sounds began to emerge. Some tracks favored sparse, percussive minimalism, while others layered rich vocals and gospel-inspired melodies.

Beyond Club Walls: The First Wave of House on Vinyl

Before the world embraced house, its earliest vinyl releases were small-batch and highly localized. Record stores like Importes Etc. and Gramaphone Records acted as nerve centers for the scene. Here, local DJs sourced the latest white-label pressings, trading new tracks and gossip about upcoming parties. These hubs were more than just shopping stops—they fostered friendly rivalries between producers and encouraged sonic innovation.

One of the biggest breakthroughs came in 1984, when Jesse Saunders released On and On, widely regarded as the first commercially pressed house record. It wasn’t long before others followed: Farley “Jackmaster” Funk’s Love Can’t Turn Around and Marshall Jefferson’s Move Your Body became instant club classics, spreading via DJ sets far beyond Chicago’s city limits. The infectious vocal hooks, thumping basslines, and uplifting piano riffs of these tracks became templates for countless imitations and evolutions.

Local labels sprang up quickly to meet demand. Trax Records and DJ International led the charge, becoming crucial launchpads for Chicago’s rising stars and cementing the city as an epicenter for musical innovation. Without major industry support, these labels relied on direct distribution to DJs and clubs—a uniquely hands-on, community-centered approach.

Mutations and Micro-Scenes: Creating Subgenres on the South Side

As Chicago House evolved, it became clear that this new style wasn’t a single sound but a growing collection of related micro-genres. The influence of local DJs like Ron Hardy at the Music Box ushered in wilder, more experimental takes. Hardy’s edits and custom versions pushed tempos higher, added distortion, and stretched tracks into sweat-soaked, raw territory. This experimentation gave birth to “acid house,” a style marked by the squelching, psychedelic tones of the Roland TB-303 bass synthesizer.

Phuture, a trio with DJ Pierre, released Acid Tracks in 1987—a single so influential that it lent its name to the entire acid house movement. Acid house was not just a new subgenre; it became a cultural code for edgier, more underground parties. Meanwhile, artists like Mr. Fingers (Larry Heard) pursued a deeper, more introspective sound with tracks such as Can You Feel It, emphasizing warm chords and soulful atmospheres instead of sheer dancefloor aggression.

The scene’s diversity kept it constantly reinventing itself. “Vocal house,” “deep house,” and “acid house” each found devoted followings, with local producers continually feeding new ideas into the mix. Rather than splintering the style, these subgenres allowed house to flourish throughout Chicago’s club circuit and, eventually, far beyond.

Breaking Borders: Chicago House Finds New Homes Overseas

By the late 1980s, Chicago’s underground success was brewing curiosity far beyond its Windy City origins. In the UK, import shops began stocking house records, and energetic DJs brought back cassette tapes after visiting Chicago. British club nights in cities like London and Manchester adopted house’s pulsating rhythms, blending them with local styles and jumpstarting entirely new scenes.

The UK’s legendary “Second Summer of Love” in 1988 saw acid house explode onto the national stage. British acts such as A Guy Called Gerald and 808 State took inspiration from Chicago but infused their own ideas, laying the foundation for rave culture. These international developments fed back into Chicago, as returning DJs shared new mixes and remixes, expanding the city’s musical vocabulary.

Meanwhile, house’s inclusivity and accessible tools—basic drum machines, affordable synthesizers—enabled bedroom producers worldwide to contribute their voices. Soon, new epicenters of house began to emerge in New York, Detroit, and European cities, each remixing Chicago’s DNA in distinctive directions.

Innovation and Endurance: Adapting to Changing Times

Chicago house’s story is not one of fossilized nostalgia, but of relentless change and adaptation. As trends shifted in the 1990s, house merged with elements of hip-hop, techno, and even pop, proving its flexibility. The emergence of ghetto house—faster, rawer, and more provocative—showed the style’s continued street-level relevance.

Legendary producers including Green Velvet, DJ Deeon, and Paul Johnson drove these transformations, embracing technology and digital tools while keeping the communal, dance-oriented spirit alive. Events like the annual Chosen Few Picnic in Chicago and global festivals paid homage to the city’s innovators, maintaining a link between past and future generations of house enthusiasts.

Moreover, modern artists and DJs continue to reference classic Chicago house tracks and methods, sampling their grooves and reviving vintage drum machines for new audiences. Online platforms, DJ streaming sets, and collaborative projects have further democratized access to the scene, ensuring that Chicago’s signature pulse remains woven into today’s nightlife and pop music.

The story of Chicago House is one of ordinary people finding extraordinary ways to connect, celebrate, and shape culture. Its journey—from modest city blocks to a worldwide phenomenon—remains unfinished, with new chapters written every time a beat kicks in at 120 BPM and someone on the dancefloor feels they belong. As fresh ideas keep surfacing, Chicago’s original vision of music as liberation and togetherness stays unbreakably strong.

Roots in the Concrete Jungle: How Chicago House Echoed Across Continents

From Local Underground to Global Pulse

Few musical genres have traveled as far and as fast as Chicago House. What began in the intimate, sweaty basements of Chicago’s club scene in the early 1980s soon reverberated throughout the world, sparking a movement that redefined the boundaries of dance music. The story of its journey is not just about sound waves crossing the Atlantic, but also about ideas of community, technology, and freedom finding new homes in unlikely places.

The DIY ethic that fueled the first house records enabled rapid proliferation. Faced with scant industry interest, producers pressed their own vinyls or relied on tape-swapping networks. Soon, DJs in cities like New York and Detroit began adding Chicago House records to their sets, drawn by the pulsing drum machines and hypnotic grooves. Even before international fame, the genre began to reshape nights in cities across America, blending into the DNA of urban nightlife wherever people longed for the dancefloor’s liberating energy.

Yet, it was in the United Kingdom where the sound of house exploded with almost unprecedented force in the mid- to late-1980s. Clubs in London, Manchester, and beyond became incubators for what would soon become the “Acid House” revolution—built on imports of tracks like Move Your Body by Marshall Jefferson and Can You Feel It by Larry Heard. British audiences, caught up in a climate of social anxiety and economic hardship, welcomed the music’s straightforward rhythms and inclusive spirit. Through these transatlantic exchanges, Chicago’s innovation laid the groundwork for a truly global scene.

Seeds of Scenes: Giving Rise to New Genres and Movements

The influence of Chicago House did not end with its original form. The genre’s straightforward patterns and soul-drenched samples provided a template that artists all over the world would adapt and mutate. In Detroit, visionary producers such as Juan Atkins and Derrick May found inspiration in Chicago’s blueprint but added layers of futuristic melodies and machine-like precision. This fusion gave birth to techno, an entirely new genre that would follow its own international path.

Meanwhile, on the West Coast, the open-minded, community-first philosophy of house spilled into what is now known as the “rave scene.” Massive warehouse parties in Los Angeles and San Francisco, echoing Chicago’s spirit, pushed the music toward harder, faster subgenres like hard house and breakbeat. In Europe, especially Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands, the arrival of imported house records led to the birth of homegrown variants such as Euro-house, Italo house, and eventually the vast universe of EDM (electronic dance music).

Through the fertile ground of house, genres like garage (notably the New York and UK variants), deep house, and the energetic, squelchy acid house took root. Each generation of producers borrowed from the past but updated the formula, making Chicago House the enduring backbone of club music.

Technology as a Bridge: Innovations Spreading the House Template

Central to Chicago House’s lasting legacy is its embrace of technology—not as a cold tool, but as an instrument of creativity, access, and rebellion. Affordable drum machines, notably the iconic Roland TR-808 and TR-909, allowed young musicians to create complex, danceable beats in their bedrooms and basements. These devices were straightforward enough for experimentation but powerful enough to define a style.

The genre’s intimate relationship with hardware democratized music-making. No longer did you need a big budget or fancy studio—just a drum machine, a few synths, a stack of records, and a vision. As a result, aspiring producers worldwide could join the movement from their homes, even if major labels or radio ignored them. This approach anticipated later developments in home recording and the digital revolution, where online platforms would put global music production in reach of anyone with a laptop and an idea.

Moreover, the culture around house involved constant remixing, sampling, and reinterpretation. DJs weren’t just playing tracks; they were reimagining them in real time. This focus on “versioning” helped to break down traditional barriers between performer and audience, fostering a participatory mindset that shaped scenes such as hip-hop, drum & bass, and even pop music in the years to come. The remix culture born in Chicago’s clubs still forms the foundation of today’s digital music universe.

Beyond Music: Shaping Identity, Style, and Community

Chicago House resonated far beyond sound—it became a catalyst for identity and collective pride. In cities facing economic downturns and social isolation, house parties offered much-needed sanctuary. Marginalized groups built informal support networks on the dancefloor, forging community ties that often spilled over into activism. The genre’s resilience and adaptability mirrored the survival instincts of those who created it.

Fashion linked closely to the house scene, with outfits cut for dancing and self-expression. T-shirts splashed with record label logos, colorful sneakers, and bold, gender-blurring looks became signals of belonging. Even outside clubs, the influence seeped into streetwear, visual art, and film, helping to define what “cool” looked like for an entire generation. For many, the freedom to express oneself through style became a vital extension of the dancefloor’s promise.

The effects also reached further: In the 1990s and early 2000s, LGBTQ+ pride celebrations, political protests, and even advertising campaigns borrowed the sounds and aesthetics of house to broadcast messages of inclusivity, hope, and resistance. Years after its first beat dropped at The Warehouse, the message remained clear: on the dancefloor, everyone was welcome.

Ongoing Renewal: House in Today’s Digital World

Decades after its birth, Chicago House continues to thrive—revived, referenced, and reinvented by every new generation of artists and fans. Modern producers such as Honey Dijon, an original Chicagoan herself, and European artists like Peggy Gou and Black Coffee, infuse the style with new life, blending classic motifs with novel production techniques.

Streaming platforms, social media, and virtual DJ sets have all played a part in bringing house to digital-era audiences. Tutorials and sample packs inspired by Chicago classics allow bedroom creators anywhere in the world to experiment with the genre’s iconic sound palette. As a form, house now unites communities globally online, just as it once did on Chicago’s city blocks.

Festivals like Amsterdam Dance Event, Movement Detroit, and London’s Fabric often devote whole nights or stages to house, tracing its Chicago roots for crowds thousands strong. The genre has become a lasting language shared by millions—celebrating unity, difference, and joy with every thump of the bass drum.

The Chicago House story, then, remains unfinished. Its echoes continue rippling outward: always finding new dancers, always daring the world to move.