Dancing Through Colombia’s Heartbeat

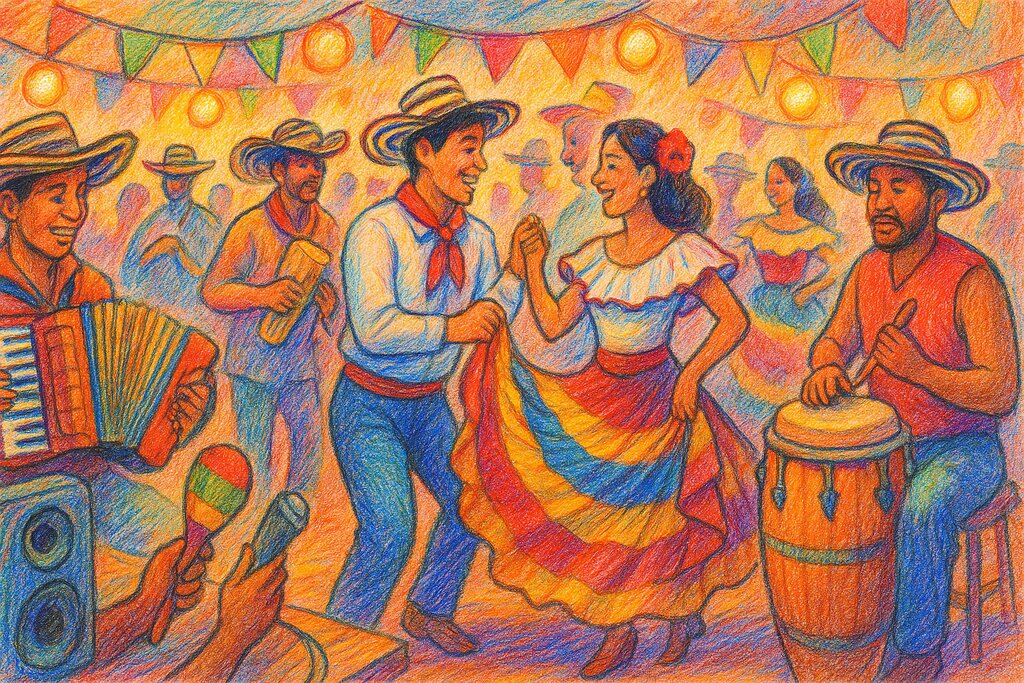

Cumbia pulses with hypnotic drum patterns, vibrant flutes, and energetic dancers in swirling skirts. Emerging along Colombia’s Caribbean coast, this genre reflects a blend of African, Indigenous, and Spanish influences that still inspire lively celebrations worldwide.

From Riverbanks to Ballrooms: The Birth and Journey of Cumbia

Roots Along the Magdalena: Where Worlds Met

To understand the origins of Cumbia, it’s essential to picture life centuries ago along Colombia’s Caribbean coast. The genre’s distinctive sound wasn’t born in isolation, but at the intersection of three cultures: Indigenous peoples of the region, enslaved Africans brought to the Americas, and Spanish colonial settlers. Each group contributed elements that would eventually blend into Cumbia’s unmistakable identity.

The oldest layers of Cumbia’s history can be traced to local Indigenous communities—most notably the Kogui and Tairona—whose ceremonial gatherings featured flutes like the gaita and persistent, trance-like drumming. Their music, originally ritualistic and closely tied to agricultural cycles, relied on simple percussive rhythms and haunting wind melodies.

As Spanish colonizers arrived in the sixteenth century, they brought the heavy realities of conquest—among them, the forced movement of Africans across the Atlantic. The Magdalena River, Colombia’s cultural artery, became not just a trade route but a crossroads for musical exchange. Enslaved Africans transported their powerful drum traditions, rhythmical complexity, and communal celebrations, quickly making their mark among local communities.

Rhythms of Resistance: African Influence and Expression

African rhythms provided the heartbeat for early Cumbia. Drums such as the tambora and alegre became vital, driving the dance with complex polyrhythms and call-and-response patterns. This musical legacy wasn’t just about entertainment—it was a form of resistance, a way for enslaved people to affirm their identities and endure hardship.

Along the riverbanks, gatherings that brought together African, Indigenous, and later mestizo (mixed-race) populations became a regular part of social life. At night, drums echoed across the water, accompanied by the wail of the gaita (a long, Indigenous flute) and the sharp rattle of seed shakers called maracas. Though Spanish authorities often tried to suppress these gatherings and ritual dances, the music thrived in secrecy, evolving in complexity and popularity.

Yet, the European influence did not remain on the sidelines for long. Spanish musical practices, with their stringed instruments and harmonic frameworks, subtly wove themselves into the evolving soundscape. This can be seen especially in Cumbia’s later use of melodies that hint at Spanish folk traditions, and in the structuring of its dance forms.

Cumbia’s Costumes and Dance: Color and Symbolism

Beyond the sound, Cumbia is a visual spectacle. The dance is a central feature, with couples moving in a circle that echoes the communal dances of both Indigenous and African communities. Women wear bright, billowing skirts—polleras—and men often sport white outfits and red scarves. These costumes don’t only add flair but symbolize the mixture of cultures and histories present in every performance.

The choreography tells stories of courtship and flirtation, its restrained steps reflecting the strict Catholic morality imposed by Spanish colonizers. However, the underlying sensuality and the vibrant energy of the dancers reveal Cumbia’s roots in pre-colonial and Afro-Colombian traditions, making each performance both a celebration and a subtle act of defiance.

Town Squares and Popularization: From Rural Festivity to Urban Craze

For centuries, Cumbia belonged to riverside villages and rural fiestas. The music marked festivals like the Fiesta de San Pedro and Carnaval de Barranquilla, blending religious and secular elements in a unique fusion. It wasn’t until the twentieth century, with changing technologies and urbanization, that Cumbia found wider audiences.

With the advent of radio in Colombia during the 1940s, the infectious rhythms of Cumbia began reaching urban centers like Barranquilla, Cartagena, and later Bogotá. Early commercial ensembles, most famously Los Gaiteros de San Jacinto and Lucho Bermúdez y su Orquesta, adapted traditional reed and drum music for larger band formats. They added instruments such as brass, clarinet, and accordion, giving Cumbia a new richness and power well-suited for urban dancehalls.

The work of Lucho Bermúdez in particular marked a turning point. His stylized arrangements of classics like La Pollera Colorá brought Cumbia to the elite ballrooms and national radio, bridging class divides and cementing the genre’s place in the Colombian mainstream. He and other bandleaders turned Cumbia into a symbol of Colombian identity—one that politicians and business leaders could embrace, even as its origins lay in marginalized communities.

Crossing Borders: Cumbia’s International Expansion

As Colombian migrants and traders moved throughout Latin America, so too did the infectious beats of Cumbia. Mid-century, steamships carried Cumbia up the Magdalena and beyond, introducing the style to neighboring countries. Panamanians, Mexicans, Peruvians, and Argentines each developed their own versions of Cumbia, adapting it to local tastes and instruments.

In Mexico, for instance, the genre was electrified—literally and figuratively. Aniceto Molina and groups like Sonora Dinamita sped up the tempo, added electric guitars, and incorporated elements from salsa and rock. In Argentina, Cumbia adopted sharper rhythms and city slang, giving birth to “Cumbia villera”—music of the urban poor that addressed contemporary social realities.

Technology played a key role in this spread. Advances in recording and broadcasting in the 1950s and 60s made it easier for musicians to reach new audiences, while cassettes and vinyl records helped knit a transnational network of Cumbia fans. Soon, the genre transcended its humble origins to become a pan-Latin American phenomenon, shaping popular music far beyond Colombia’s borders.

Resilience Through Repression and Change

Despite its wide appeal, Cumbia’s journey was not without struggle. Throughout its history, authorities—both colonial and modern—often viewed the music and its dances with suspicion. They associated large gatherings with disorder and potential rebellion. Efforts to ban or sanitize Cumbia were common, especially during periods of political instability.

Yet, rather than stifle the music, these attempts often helped it evolve. Musicians and dancers found creative ways to evade censorship, blending coded language and hidden motifs into their performances. What survived was not just a party soundtrack, but a form of expression that could carry hopes, sorrows, and political sentiment.

Today, echoes of those struggles ring out in contemporary Cumbia lyrics, which touch not only on love and festivity but also on inequality, migration, and resilience.

Echoes in the Present: Heritage and Modernity

Cumbia’s long path from riverside gatherings to global dancefloors illustrates its extraordinary adaptability. In Colombia, traditional Cumbia remains a living art at festivals and in small towns, vigorously preserved by groups like Los Gaiteros de San Jacinto and celebrated during community events. Meanwhile, urban artists remix Cumbia rhythms with electronic beats, reggae, and hip hop—demonstrating the genre’s resilience and endless capacity for reinvention.

The evolution of Cumbia stands as testament to the power of cultural exchange—how tradition, migration, and innovation can come together to shape the soundtrack of a nation, and ultimately, the world. Its story is not static, but a continuing celebration, tracing the journeys of those who created it, and of new generations who make it their own.

The Sound of Celebration: Inside Cumbia’s Musical DNA

Infectious Rhythms: Drums That Call to Dance

A central pillar of Cumbia’s musical identity lies in its driving percussion. From the earliest days by the banks of the Magdalena River, the beat of the drum has signaled more than just music—it has been a call for people to come together, celebrate, and share stories. The sound of drums in Cumbia is not simply background accompaniment; it forms the backbone around which every instrument and dancer orbits.

The most iconic percussion instruments in Cumbia are the tambora, alegre drum, and llamador. Each carries both functional and cultural meaning. The tambora kicks off the rhythm with a deep, resonant thump, setting a steady foundation. It’s played with sticks, offering a booming, steady pulse. The alegre, often called the “happy drum,” brings energy and liveliness with quicker, syncopated patterns played with the hands. Meanwhile, the llamador—meaning “the caller”—adds sharp accents, calling musicians and dancers alike to attention and ensuring the groove stays locked in throughout.

Notably, these drums aren’t interchangeable. Each player trains for years to master their specific role, and within a traditional setup, the dialogue between them reflects centuries-old African traditions. In Cumbia, the rhythmic patterns are cyclical, encouraging trance-like movement and signaling transitions for dancers. The interplay rivals even the call-and-response drumming of West Africa, echoing roots that span continents.

Moreover, percussion in Cumbia is an art of nuance as much as power. The subtle variations in intensity and tempo—how a drummer accelerates for a particularly spirited dance section, or softens for a more intimate moment—demonstrate the expressiveness at Cumbia’s core. Live performances often feature brief, improvised drum solos, holding audiences in thrall and building anticipation before the main melody returns.

The Whisper of the Flute: Melodies That Tell a Story

Layered above these percussive currents is a melodic component that is just as essential—the haunting song of the gaita. This traditional flute, crafted from cactus stems and beeswax, delivers a distinctly earthy tone that immediately marks a song as Cumbia. There are two types: gaita hembra (female) and gaita macho (male), each providing a unique voice in the ensemble.

The gaita hembra leads with winding melodies, while the gaita macho offers rhythmic counterpoints, often repeating short motifs or providing simple harmonies. The dialogue between the two harks back to Indigenous ceremonial music, which used wind instruments to mark the passage of time or celebrate harvests. Although the instrumentation has grown over centuries, the gaita flute remains central to traditional Cumbia ensembles—especially among groups aiming to preserve precolonial authenticity.

Over time, musicians have introduced other melodic instruments to the Cumbia mix. The caña de millo, a single-reed flute, became especially popular on the Atlantic coast. Likewise, contemporary Cumbia sometimes features the clarinet or saxophone, especially in urbanized versions. However, at its roots, Cumbia’s melody always circles back to the flute’s plaintive, wandering character—both a nod to Indigenous heritage and a testament to the genre’s emotional range.

The Chime of Strings and Song: Evolving Harmonies

While percussion and flutes form the core of Cumbia’s original sound, string instruments began to shape its character as the genre spread from rural festivities to urban dance halls. The introduction of the guitar, bass, and even the accordion—especially in later, hybrid styles known as cumbia moderna—show how Cumbia has continually adapted without losing its rhythmic soul.

The guitar entered the scene in the mid-20th century, weaving harmonies that enriched the music’s texture. As the genre moved into the cities of Colombia and beyond, the electric bass provided a deep foundation that was more easily heard in large venues and blended well with the growing brass sections. Meanwhile, the accordion—borrowed from neighboring vallenato—gave birth to entire new sub-genres, like cumbia sabanera and cumbia villera, each with its regional flavor and social dynamics.

Vocals, meanwhile, have always played a pivotal role in the Cumbia ensemble. Traditional songs are often performed in call-and-response, echoing both African and Indigenous music-making. Lyrics dwell on themes of love, work, celebration, and the natural world. In classic songs like La Pollera Colorá and Cumbia Cienaguera, singers paint stories of joy and longing, working in harmony with the orchestra of drums and flutes below.

Furthermore, in modern urban settings, vocals sometimes shift toward solo singing—mirroring the influence of international pop and salsa. Yet, even these innovations tend to circle back to stories rooted in communal life and shared traditions.

Rhythm Beyond Borders: Adaptability and Fusion

One of the most remarkable traits of Cumbia is its ability to adapt while remaining recognizably itself. As the genre traveled outside Colombia—arriving in Mexico, Argentina, Peru, and now global cities—musicians adopted local instruments and social themes, but always preserved the genre’s essential rhythmic engine.

For example, in Mexico, Cumbia incorporated electric guitars, synthesizers, and drum kits, giving rise to styles like cumbia sonidera and cumbia norteña. In Argentina, the genre took on a sharper, more pronounced beat, becoming known as cumbia villera, which conveys the stories of urban life in Buenos Aires through both electronic and traditional instrumentation.

Yet across these styles, the conga-like rhythm, syncopated accents, and melodic motifs persist. Audiences in Lima or Monterrey may dance to electrified beats, but the structure—built on intertwined percussion and melodic lines—echoes the gatherings that once lit up the Magdalena’s shores. Songs like Cumbia sobre el Río by Celso Piña or Yo Tomo by Grupo 5 reveal not only regional twists, but also the genre’s enduring international spirit.

Even in digital production, Cumbia’s DNA shines. Producers sample and remix archival drum breaks or flute phrases, bridging the gap between ancient rituals and contemporary dance floors. This ability to balance nostalgia and innovation keeps Cumbia resonant for new generations.

Costumes, Instruments, and Movement: A Complete Sensory Experience

To understand Cumbia’s musical character, it’s essential to look beyond the notes. Every live performance draws together costumes, choreography, and ritual: swirling skirts, feathered hats, candlelit processions, and communal circles of dancers. The music is inseparable from the colorful spectacle around it.

Musicians meticulously tune and decorate their instruments, giving each performance distinctive sounds and visuals. The wooden maracas rattle in sync with swirling dancers; the shimmer of a sequined dress coincides with a sudden drum flourish.

This interplay between music, image, and movement reinforces Cumbia’s collective energy. Whether in a Colombian town square or a festival stage halfway around the globe, Cumbia brings together multiple senses, turning every celebration into a living reminder of its roots and capacity for reinvention.

The genre’s continued evolution—whether by swapping out instruments, incorporating electronics, or mixing languages—offers a window into how traditions stay alive. New voices and ideas move through Cumbia, but the original pulse, call of the flute, and stories of the pueblo endure, inviting the world to join the circle and dance.

Vibrant Offshoots and Regional Flavors: How Cumbia Became Many

Old Traditions, New Directions: The Birth of Cumbia Variants

As Cumbia made its way from Colombia’s riverbanks to dance halls across the country, it didn’t remain a static tradition. Instead, it started branching out, adapting to local tastes, instruments, and rhythms wherever it landed. In Colombia alone, different towns and regions infused Cumbia with unique signatures. What began as a rural ritual evolved into both a popular street party soundtrack and a polished ballroom classic.

The classic or traditional Cumbia—sometimes called Cumbia sabanera—remains rooted in indigenous and African drumming, with the haunting sound of the gaita flute calling through the air. Villages along the Caribbean coast still perform Cumbia with its celebratory circle dance and vivid costumes, staying close to its origins. Yet, even here, subtle variations exist from town to town. For example, the Cumbia performed in Barranquilla’s grand Carnival parades often features larger orchestras and theatrical choreography, a contrast to the more intimate village ceremonies.

In contrast, as Cumbia hit Colombia’s bustling urban centers, it began to change character. City musicians, eager to reach new audiences, started experimenting. They introduced brass instruments, accordions, and even electric guitars into the mix, blending Cumbia with other popular genres like porro and vallenato. Record labels in Bogotá and Medellín in the 1950s helped solidify this “modernized” sound, producing artists such as Lucho Bermúdez, whose arrangements added lush horn sections and a smoother, cosmopolitan feel to traditional Cumbia.

Crossing Borders: Cumbia’s Incredible Journey Across Latin America

Cumbia did not stop at Colombia’s borders. The rhythm spread like wildfire, carried by migrants, radio broadcasts, and records, transforming as it entered new countries. Each nation along Cumbia’s path embraced the genre, recasting it through local musical traditions and social realities.

One of the most influential adaptations took place in Mexico. By the 1940s and 1950s, Cumbia began to appear on Mexican airwaves. Musicians there—fascinated by its infectious rhythm—started incorporating the accordion, giving rise to what’s known as Cumbia mexicana or Cumbia sonidera. The Sonidero movement, deeply tied to urban Mexico City culture, took off in the late twentieth century, with DJs and sound systems blending Cumbia recordings with elements of salsa, rock, and electronic music. Local acts like Rigo Tovar reimagined Cumbia with electric bass, synthesizers, and a distinctly Mexican identity, turning it into national party music.

Moving south, Peru saw the birth of its own, dazzling variation: Chicha or Cumbia peruana. Emerging in the late 1960s in the working-class areas of Lima and the surrounding Amazon regions, Chicha’s key difference lay in its embrace of electric guitars, surf rock-influenced riffs, and touches of psychedelic sound. Bands such as Los Mirlos and Los Shapis became trailblazers, using traditional Cumbia beats as a base but layering them with vibrant, twangy melodies and lyrics that spoke to daily struggles and migration. Chicha’s danceable rhythms and raw energy made it a favorite at local festivals and street parties, reflecting both the struggles and joys of urban Peruvian life.

Meanwhile, in Argentina, Cumbia villera rose from the outskirts of Buenos Aires in the late 1990s. Named after the city’s working-class villas miseria (shantytowns), this subgenre captured the realities of social marginalization and economic hardship. Its lyrics often address crime, poverty, and romance, using synthesizers and drum machines to create a punchy, electronic groove. Groups like Damas Gratis and Los Pibes Chorros brought Cumbia to the forefront of youth culture, making it the soundtrack for an entire generation of Argentine urbanites.

Style Shifts: How Technology Sparked New Cumbia Experiments

The evolution of Cumbia did not rely only on regional reinterpretations. Changes in technology, both in instrument-making and in recording, created opportunities for experimentation that pushed Cumbia in new directions.

With the arrival of the electric guitar and keyboard in the mid-twentieth century, a world of new sounds opened up. These technologies made it possible for bands to play Cumbia with smaller, portable setups, expanding opportunities for touring and performance. As early as the 1970s, Peruvian groups like Juaneco y Su Combo were experimenting with fuzz pedals and electronic organs, blending traditional rhythms with the rock and roll energy that locals craved. Their records, sold at neighborhood markets and played at family parties, became emblematic of how Cumbia could quickly adapt to changing cultural landscapes.

In recent years, digital technology has fueled even more boundary-pushing. Producers in Argentina, Mexico, and the United States now craft Cumbia digital—an electronic approach that samples traditional rhythms but situates them in the world of electronic dance music (EDM), hip-hop, and reggaeton. Acts like Bomba Estéreo from Colombia create global hits by layering age-old drum patterns with modern synths and basslines, making Cumbia irresistible on international dance floors. This modern twist reflects how Cumbia, while rooted in ancient traditions, eagerly moves with the times.

Social and Cultural Meanings Behind the Music

The proliferation of Cumbia styles is not just a musical story—it also reveals deeper social and cultural dynamics at play. Each variation grew out of specific conditions: migration, changing class structures, technological advances, and shifting youth identity.

In the Mexican barrios, Cumbia became the music of street parties, backyard gatherings, and urban celebrations. The sonidero scene reflects both a love of tradition and a playful embrace of musical change, as DJs remix and shout personalized messages over the thumping Cumbia beat. For these communities, Cumbia serves as both a cultural anchor and a means of communal expression, giving neighborhood parties a distinctive soundtrack that fuses Colombian influence with Mexican creativity.

In Peru, Chicha embodies the realities of rural-to-urban migration. Its lyrics, sung in both Spanish and the indigenous Quechua language, speak to the hopes, hardships, and humor of those finding their place in rapidly growing cities. The mixture of electric instrumentation and Amazonian folk melodies captures a hybrid identity that sits at the heart of modern Peruvian society.

The story is similar in Argentina, where Cumbia villera functions as a voice for the voiceless. While mainstream media often stigmatizes this music for its raw lyrics and “outlaw” image, fans see it as an honest reflection of everyday experiences. Cumbia villera gatherings become spaces for young people to define themselves and push back against social exclusion through dance and collective celebration.

Moreover, in every context, Cumbia’s shifting forms signal the adaptability of musical tradition. Whether played on wooden flutes by Caribbean fishermen, blaring out from neon-lit dance halls, or remixed on a laptop, Cumbia serves as a living, breathing chronicle of cultural transformation—a genre always moving forward, always open to reinvention.

As new generations of artists and fans return to Cumbia’s roots while dreaming up future possibilities, the music continues its journey—its beat as insistent and infectious as ever.

Legends, Trailblazers, and Anthems: Shaping Cumbia’s Global Story

The Founding Pulse: Origins Through Iconic Maestros

When discussing who brought Cumbia to life and defined its earliest masterpieces, it’s impossible to overlook the pivotal contributions of Lucho Bermúdez. Born in 1912 in the Colombian town of Carmen de Bolívar, Bermúdez was not just a gifted composer and clarinetist—he became Cumbia’s first great modernizer. Starting in the 1940s, Bermúdez reimagined Cumbia’s rural identity, infusing it with sophisticated arrangements for big-band orchestras. By doing so, he helped Cumbia leap from village fiestas to urban dance halls and radio stations nationwide.

One of his most memorable works, Danza Negra (1946), remains both an anthem and an emblem for the genre’s Afro-Colombian roots. This piece doesn’t just showcase pounding percussion and swirling flutes—it spotlights clever harmonies and brass sections that were new to Cumbia at the time. Bermúdez’s Prende la Vela became another signature track, holding a special place in Colombian music history for its joyful, danceable energy. These recordings, brimming with both respect for tradition and innovative arrangements, set the template for future musical developments.

Moreover, Bermúdez’s orchestra toured internationally, exposing audiences across Latin America to Cumbia’s irresistible rhythms. These tours, especially his legendary 1950s performances in Mexico and Cuba, played a major role in seeding Cumbia’s spread throughout the continent. His influence can be heard not only in the music itself, but also in how Cumbia shaped Colombian national identity during a period of dramatic modernization.

Alongside Bermúdez, Pacho Galán stands as another transformative force in early Cumbia. Known for blending Cumbia with other Colombian rhythms like porro and merecumbé, Galán created a unique hybrid sound that appealed to a wider spectrum of listeners. His vibrant track Cumbia Alegre exemplifies an open, festive spirit—attracting dancers from every generation and background. Galán’s approach reaffirmed that Cumbia, for all its ritualistic and rural roots, could reinvent itself without losing its essential character.

Matriarchs and Guardians: Women at the Heart of Tradition

While grand orchestras and urban innovations shaped Cumbia’s mainstream identity, women played vital, if sometimes under-acknowledged, roles in preserving its essence. Among the most revered is Totó La Momposina—a trailblazer in bringing traditional Cumbia to a global audience.

Born Sonia Bazanta Vides in 1940 on the banks of the Magdalena, Totó’s lifelong dedication to Afro-Indigenous traditions has made her a living repository of Cumbia’s roots. Her performances spotlight not only the polyrhythmic drumming and gaita flutes central to the genre, but also traditional circle dances and vocal techniques handed down through generations. The album La Candela Viva (1993), which brought her to international fame, features powerful renditions of classics like El Pescador and Cururú. In these songs, the enchantment of riverside nights and community gathering are palpable.

Totó’s role extends beyond music. As an educator, she’s mentored new generations in the coastal towns, ensuring Cumbia’s living traditions continue to thrive far from recording studios. Her Grammy-winning efforts reflect Cumbia’s endurance through turbulent decades and changing fashions. Importantly, her music bridges Colombia’s ethnic and gender divides, amplifying women’s voices and placing traditional arts at the center of national conversation.

Cumbia Crosses Borders: The International Explosion

No discussion of Cumbia’s key figures and works would be complete without exploring its international expansion—especially its massive popularity in Mexico and Argentina. As Cumbia traveled, different countries adapted it to their own styles, instruments, and cultural settings.

In Mexico, Rodolfo y su Tipica RA7 are often cited as early pioneers who fused Colombian classics with Mexican rhythms and electronic textures in the 1970s and 1980s. Their version of Cumbia Sampuesana took the original Colombian melody and electrified it, making it a staple at parties across Mexican cities and towns. As radio and cassettes carried the sound northward, Cumbia quickly integrated into the Mexican soundscape.

Eventually, Cumbia Sonidera emerged, characterized by the use of synthesizers, electric guitars, and local slang in the lyrics. Bands like Los Ángeles Azules from Iztapalapa, Mexico City, took this sound to unprecedented commercial heights. Their 1990s hit Cómo Te Voy a Olvidar redefined what a Cumbia anthem could be—balancing nostalgia, danceability, and pop accessibility.

In Argentina, innovators such as Damas Gratis pushed the genre into new territory. Their approach, known as Cumbia villera, is marked by gritty lyrics reflecting life in urban neighborhoods and a heavy use of keyboard-led hooks. Songs like La Cumbia de los Trapos exemplify the genre’s role as both party soundtrack and vehicle for social commentary. Here, Cumbia becomes a voice for those rarely featured in mainstream media, using infectious beats to address daily struggles and dreams.

What ties these international variants together isn’t just a shared musical DNA, but a common adaptability. The Cumbia beat proves elastic enough to absorb everything from brass bands and marimbas to electronic drum machines—accommodating generation after generation of innovators.

Essential Anthems: The Tracks That Changed Everything

Throughout Cumbia’s history, certain compositions have become more than just songs—they are rituals, played at every family gathering, carnival, and festival. One of the most influential remains La Pollera Colorá, first recorded in the 1960s by Wilson Choperena and Juan Madera Castro. This track didn’t just sweep Colombian dance floors; it became a symbol of national pride. Its swirling flutes, lively drums, and jubilant lyrics celebrate the famous “colored skirt,” evoking images of spinning dancers and endless fiesta nights.

Another milestone hit is Cumbia Cienaguera, initially composed by Guillermo de Jesús Buitrago in the mid-20th century and since interpreted by dozens of orchestras and bands across Latin America. Its playful yet hypnotic rhythm invites everyone—young and old—to join the circle and dance. The song’s enduring appeal lies in its ability to be both deeply local and universally inviting.

The iconic El Pescador, popularized by Totó La Momposina, evokes life along the Magdalena River, blending vivid lyrics about daily labor with rhythm patterns that connect listeners to ancestral traditions. This song, like so many others, stands as living proof of Cumbia’s emotional depth, built on both memory and movement.

Perhaps the best example of Cumbia’s constant reinvention is La Cumbia del Río, whose catchy chorus and electronic flourishes speak to younger generations while keeping a pulse on tradition. It underscores that even as technology and tastes evolve, the heart of Cumbia—its invitation to dance—is unchanging.

Modern Innovators: Keeping the Beat Alive

As Cumbia continues to evolve, artists like Bomba Estéreo are pushing its boundaries even further. Known for their energetic fusion of traditional rhythms with electronic beats, this Colombian band opened Cumbia up to global pop and indie audiences. Their breakout track Fuego pulses with both Afro-Colombian percussion and synthetic bass lines, showing how ancient festival patterns thrive in modern-day dance clubs.

Meanwhile, musicians in Peru, Argentina, and the United States now sample classic Cumbia tracks, remixing them for new contexts—digital platforms, music festivals, or socially conscious art. This spirit of remixing and reinvention honors Cumbia’s history as a genre of encounter and exchange, alive to every new wave of innovation.

Ultimately, Cumbia’s enduring legacy is built not just on a handful of icons or anthems, but on its community-driven, ever-changing nature. With each generation and migration, it expands its reach—remaining a soundtrack for celebration, protest, and everyday life. The journey of Cumbia continues, promising new voices, fresh variations, and dances yet to be invented.

Beyond the Rhythm: Crafting Cumbia’s Unique Soundscape

Layer Upon Layer: Instrumentation as Conversation

Unearthing what makes Cumbia instantly recognizable means turning attention to its intricate web of sound. At first listen, the genre’s rhythm might seem simple—a steady pulse, pulled along by the strong, insistent beat of the tambora. Yet, zoom in, and a far more elaborate system of roles emerges. Each percussion instrument, from the bright alegre to the crisp llamador, behaves like a voice in an ongoing musical dialogue. This isn’t a random stack of rhythms. Every player carefully fits into a time-honored structure, reacting and responding to the others with subtle variations. What may feel like spontaneous energy on the dance floor is actually the result of deep musical discipline and codified tradition.

Adding more color, the gaita—a long indigenous flute made from cactus stalk—floats above these percussive exchanges. Its nasal, expressive tone is impossible to miss, often taking the lead with playful improvisations or plaintive melodies. And when Cumbia performances expand for larger audiences, additional elements like the clarinet, accordion, and brass instruments step in, broadening the harmonic foundation. The music swells from an intimate trio to a lively orchestra, but it never abandons its foundation rooted in polyrhythmic interplay. Throughout, each voice remains crystal clear—a testament to Cumbia’s careful balance between complexity and danceability.

Furthermore, regional variations incorporate unique voices into the ensemble. For example, in northern Colombia’s Cumbia sabanera, the guache—a metallic shaker—and the maracas reinforce and brighten the overall groove, inviting energetic footwork from dancers. Urban versions might blend in modern electronic keyboards or even electric guitars, but they always respect the blueprint forged by the traditional percussion and wind instruments.

The Pulse Does Not Lie: The Mechanics of Cumbia Rhythm

At the living heart of Cumbia is its rhythm, forged from centuries of musical fusion. Unlike Western pop where time is often measured in strict, symmetrical patterns, Cumbia’s groove leans into what musicians call a “polyrhythm.” This means several distinct rhythms play out at once, stacked together like puzzle pieces. The tambora lays a ground-level foundation—reliable, deep, and measured. Above this, the alegre cuts in with dazzling, syncopated flourishes. Its patterns are loose but precise, sliding just ahead or behind the basic beat, teasing dancers to follow. Meanwhile, the llamador stands guard, maintaining the tempo with regular, sharp strikes, preventing the ensemble from losing its collective pulse.

What’s fascinating about these layers is their interactive quality. If one rhythm shifts, the others adapt instantly, creating a living, breathing groove that responds to its environment—be it an outdoor celebration or a formal ballroom. This flexibility distinguishes Cumbia’s rhythm from other Latin genres, such as salsa or merengue, which usually anchor themselves to a rigid clave pattern. Instead, Cumbia thrives on rhythmic asymmetry and call-and-response, echoing the communal spirit at its origin.

Musicians learn these structures not just from sheet music, but through aural tradition. Sons and daughters in musical families often join in from a young age, internalizing the patterns before ever playing a formal note. This results in performances that are both technically tight and emotionally loose, able to stretch and contract organically with the mood of the event.

Arranging the Journey: Structure and Song Forms

Although its roots are found in improvisational rituals and processions, Cumbia songs follow distinctive forms that shape the listener’s experience. A traditional piece typically begins with an instrumental section called the introducción, where the melody—often played by the gaita or clarinet—is unveiled. Then, vocals enter with verses and a repeating chorus that listeners soon join. These sections trade places, shifting the spotlight from instrumental textures to communal singing and back again. Each verse usually tells a story drawn from daily life or regional folklore, blending the personal and the collective.

Yet, within this familiar architecture, there’s room for constant innovation. A skilled bandleader knows when to open up the arrangement, inviting solos or breakdowns where new melodies or rhythmic patterns can emerge. This balance between predictability and surprise is central to the genre’s broad appeal.

One clear example of creative arrangement comes from Lucho Bermúdez, who transformed rural Cumbia for big band formats in the 1940s. He introduced extended instrumental passages and harmonized horn sections, elevating Cumbia from a local dance form to a showpiece for sophisticated urban audiences. His work, heard on tracks like Danza Negra and Prende la Vela, demonstrates how adaptation of structure and instrumentation can renew even the oldest genres.

The Studio Revolution: Recording, Amplification, and Adaptation

With the rise of the record industry in Latin America during the mid-20th century, Cumbia faced a new challenge—how to preserve its complex sound on vinyl. Early recordings relied on live takes with minimal technological assistance, capturing raw, unfiltered energy but sometimes sacrificing clarity. As the genre’s popularity exploded, advances in multi-track recording enabled producers to layer instruments more meticulously. Percussion tracks were separated, allowing each drum’s character to shine. This new fidelity revealed the subtle interactions between parts, making records less a blur of sound and more an intricate tapestry.

Amplification brought another shift. As dance halls grew larger and audiences more demanding, electric microphones and PA systems ensured that even delicate instruments like the gaita and maracas cut through the excitement. Bands could now experiment with effects: reverbs for echoing passages, filters for experimental tones. It wasn’t long before electric guitars and synthesizers appeared, especially in the urban Cumbia scenes of Mexico and Peru. These tools didn’t erase tradition; rather, they expanded the creative palette, giving artists like Mexico’s Rodolfo y su Tipica RA7 or Peru’s Los Mirlos the freedom to craft music that sounded both ancient and futuristic.

This interplay between technological innovation and musical identity continues to shape Cumbia today. Musicians still strive to keep the earthy warmth of folk traditions even as digital tools offer new directions. Modern producers might use sampling to weave snippets of old recordings with fresh beats, but the spirit of Cumbia remains rooted in that distinctive, polyrhythmic groove that first brought people together by the river.

A Living Tradition: Flexibility at the Core

What truly sets Cumbia’s technical foundations apart is its adaptability. No two performances are identical, because the musicians themselves are always in dialogue with the moment—adjusting tempos, extending improvisations, teasing the crowd. Dancers, too, shape the nightly version of the music; their footwork might push the pace or draw the percussionists into bursts of energy. The music is meant to breathe and respond.

This blend of structure and spontaneity has allowed Cumbia to travel, adapt, and thrive not only across Latin America but in communities around the world. Wherever the core blueprint arrives, local musicians add their voices and instruments—the accordion in Argentina, electric bass in Mexico, even turntables in digital Cumbia scenes—reminding us that the genre’s technical DNA is always open to new mixtures.

Such constant reinvention, layered on bedrock tradition, ensures that the technical art of Cumbia will continue to inspire new generations of listeners and musicians—still connecting people, still calling them to dance, and still telling stories beyond words.

A Dance for All: Cumbia’s Social Heartbeat Across Continents

Celebration, Identity, and the Power of Community

When you step onto a dance floor pulsing with the unmistakable rhythm of Cumbia, you’re not simply joining a party—you’re participating in a tradition deeply rooted in Latin American life. From its beginnings along Colombia’s Caribbean coast, Cumbia has long been more than a musical genre. It holds a vital place in the fabric of daily existence, acting as a social glue that brings people together for celebration, solidarity, and collective memory.

Historically, Cumbia’s origins are nestled within the intermingling of Indigenous, African, and Spanish cultures. The music and dance grew out of gatherings where enslaved Africans and local Indigenous groups, often marginalized and excluded from colonial institutions, could express their sorrows, joys, and aspirations. The communal circle dance, where women in flowing skirts spun around torch-carrying men, provided more than entertainment. It became a living expression of perseverance and community strength in the face of adversity.

The language of Cumbia—its drumbeats, its syncopated steps, its ritual choreography—helped multiple cultures find a shared voice. Villages would come alive with these sounds during important festivals, family gatherings, and public celebrations. Over generations, Cumbia songs evolved into musical time capsules, holding stories, jokes, and social commentary particular to each region.

Cumbia’s social role has not merely persisted but grown stronger across years and borders. As people from rural areas moved to Colombian cities in search of work, they took their traditions with them. In bustling city streets, Cumbia transformed yet again, adapting itself to public dances known as casetas and mass celebrations like the Barranquilla Carnival. In these new settings, the music’s fundamental spirit—joyful, welcoming, and never exclusive—continued to shine through, making it an anthem of togetherness and cultural pride.

Breaking Barriers: Cumbia as a Symbol of Mestizo Identity

One of the most powerful ways Cumbia shapes Latin American culture lies in its reflection of national and collective identity. Across Colombia and far beyond, the genre is held up as an authentic symbol of mestizaje—the blending of Indigenous, African, and Spanish heritages that defines much of the region’s history.

This ability to bridge backgrounds has made Cumbia an unofficial national soundtrack in Colombia. For decades, it’s been played at every conceivable occasion—political rallies, school graduations, religious festivities, and even somber moments of remembrance. Its inclusion in the curriculum of music schools, as well as its ubiquitous presence at holiday parties, speaks to how deeply the genre is woven into the cultural DNA.

Celebrated artists like Totó la Momposina have taken up the role of cultural ambassadors, carrying Cumbia’s message of unity into the global spotlight. Her performances are not only concerts but also lessons in heritage, with call-and-response singing and theatrical dress evoking the celebrations of the Magdalena River delta. Through artists like her, Cumbia’s reputation as a music of mestizo pride has reached audiences worldwide, showing that cultural fusion can be an engine for creativity and resilience.

In a society frequently marked by regional divisions and social inequalities, Cumbia’s populist appeal is striking. Unlike elite-oriented classical music or imported pop genres, Cumbia is owned and enjoyed by all. Tailors, lawyers, market vendors, and students alike move to the same irresistible rhythms, proving that Cumbia’s embrace knows no social or economic barriers.

Across Borders: The Journey to Continental Icon

Cumbia’s cultural power didn’t stop at the Colombian border. By the middle of the twentieth century, it was already crossing into neighboring countries, gathering new flavors and meanings along the way. As Cumbia reached Mexico, Peru, and Argentina, local musicians adapted its form, reflecting their own histories and social contexts.

In Mexico, for example, the emergence of Cumbia Sonidera in the urban neighborhoods of Monterrey and Mexico City marked a fresh wave of innovation. DJs known as sonideros began mixing classic Colombian Cumbias with electronic beats, Spanish-language rap, and local slang. These parties quickly became hubs of migrant life and signs of urban identity, especially among young people searching for belonging in sprawling megacities.

Meanwhile, in Argentina and Chile, Cumbia mutated into styles like Cumbia villera and Cumbia chicha, each reflecting new social realities. Cumbia villera, born in the working-class neighborhoods of Buenos Aires, used rough-edged lyrics and electrified sounds to comment on poverty, exclusion, and hope. Rather than a simple inheritance of tradition, Cumbia became a creative weapon for communities striving to be seen and heard in rapidly changing societies.

Through each adaptation, the spirit of Cumbia remained at its core: irrepressibly festive, inclusive, and socially conscious. Local versions kept rituals like communal dancing and collective singing alive, helping anchor newly arrived migrants in their adopted cities. This cross-pollination of styles showed, above all, that Cumbia could absorb new influences without losing its foundational values.

Soundscape of Protest, Resistance, and Change

Interestingly, Cumbia’s role as a music of celebration has often dovetailed with that of resistance. Long before political protest songs became fashionable in Latin America, Cumbia’s lyrics and performances served as subtle platforms for criticism and unity. Its simple melodies and repeating choruses could disguise sharp social commentary or hidden codes beneath the surface.

During Colombia’s turbulent political eras—the times of civil conflict, movements for workers’ rights, and pushes for land reform—Cumbia provided both relief from hardship and a tool for collective action. In classic songs such as La Pollera Colorá, beneath the joyful melody lies a quiet assertion of feminine power and ethnic pride. Street performers and rural bands would cleverly adjust lyrics in real time, referencing major news events or local injustices. This adaptive quality allowed Cumbia to feel endlessly relevant, always ready to respond to the latest struggles or triumphs.

Cumbia bands have been present at countless demonstrations, festivals for peace, and cross-cultural events, further cementing the idea that these rhythms belong to everyone. Through radio broadcasts and cassette tapes, its messages have reached isolated villages and urban marginals alike, providing a sonic thread that binds people’s collective struggles and aspirations.

Cumbia’s Place in Everyday Life: From Birthdays to Political Change

If you visit a Colombian town during a holiday or attend a family milestone anywhere in Latin America, chances are you’ll hear Cumbia. From the biggest city squares to the smallest village patios, these rhythms have become a soundtrack for life’s milestones. Weddings, birthdays, New Year’s Eve parties, and even funerals unfold to the sounds of the tambora, the gaita, and booming choruses.

That same presence can be felt during national celebrations, such as Carnaval de Barranquilla or local ferias, where performers dressed in dazzling costumes turn tradition into living theater. Here, Cumbia is not just background entertainment—it’s a participant in rites of passage and collective memory.

More recently, as Cumbia continues to evolve through pop fusions and new digital production, its social significance only deepens. Independent labels and social media have enabled young musicians to remix and reinterpret Cumbia for contemporary audiences, ensuring that its place within daily life adapts to new generations. This constant reinvention guarantees Cumbia’s enduring role as a crucial thread in the dynamic tapestry of Latin American identity—today and always.

From Carnival Nights to Global Stages: Living and Breathing Cumbia

Tradition Comes Alive: Cumbia in Its Native Setting

Step into a bustling Colombian plaza at dusk, and you witness the true spirit of Cumbia. The air hums with anticipation as drummers gather, flautists tune gaitas, and dancers adjust their vivid outfits. In towns along the Caribbean coast, such as Barranquilla and Cartagena, festivals like the legendary Carnaval de Barranquilla explode each year with a kaleidoscope of color, sound, and communal energy. Cumbia isn’t a genre locked in the past; it’s an ever-renewing ritual, lived by communities who pass down steps, lyrics, and rhythms from one generation to the next.

Inside these traditional scenes, performance is far more than entertainment. The circular formation of dancers—women in wide, swirling skirts and men dressed sharply—evokes ancient ceremonies of courtship and cultural exchange. Torches or candles are still carried by participants, symbolizing the fiery African and Indigenous roots at the music’s core. The repetition of steps, the call and response between musicians, and the communal chorus—all combine to blur the line between artist and audience. In these moments, Cumbia is both a carefully preserved tradition and a wild, collective celebration.

The Evolving Stage: Urban Halls, Dance Clubs, and Parades

Although its roots dig deep into village life, Cumbia has long outgrown the confines of rural Colombia. Since the 1940s, urbanization and migration brought the genre into the heart of major cities. In bustling dance halls of Bogotá and Medellín, refined versions of Cumbia began to circulate, courtesy of big bands led by innovators like Lucho Bermúdez. These concerts featured expanded ensembles—adding clarinets, brass, and even early electric microphones—enabling Cumbia to reach wider and more varied audiences.

What truly distinguishes Cumbia’s spread is the way live performance has always adjusted itself to its surroundings. In the 1960s and 1970s, when Cumbia swept across Latin America, it became a centerpiece in carnivals, wedding fiestas, and even political rallies. Dance floors filled with people eager to take part in its infectious rhythms and learn the latest steps from local instructors. It’s not unusual for bands to extend songs for dancers, responding in real-time to the crowd’s energy.

As Cumbia moved into clubs, street parties, and television studios, live performances adapted yet again—sometimes swapping out traditional flutes for electric keyboards or adding flashy costumes and lighting effects. Nevertheless, one aspect stayed unchanged: the music’s direct invitation for everyone present to become part of the show, whether as a dancer, a singer, or simply by clapping along.

The Mechanics of Cumbia Performance: Tension, Joy, and Artistry

Inside every Cumbia performance lies a careful balance between discipline and spontaneity. Percussionists anchor the rhythm with patterns learned through years of practice, while lead vocalists improvise verses about local stories, romance, or social troubles. This interplay creates a constant sense of tension and release, keeping dancers returning to the floor. Musicians often nod or gesture to signal changes, orchestrating shifts in mood, tempo, or instrumental focus without ever pausing the beat.

Moreover, dancers interpret the music visually. In the women’s wide, skirt-driven twirls and men’s precise sidesteps, each movement mirrors melodic phrases or syncopated percussion fills. In live settings, these performers don’t merely follow routines—they react to every accent, every improvisation, and every cheer from the audience. This reflexive relationship gives Cumbia performances an organic, almost conversational quality, different each time they unfold.

Live Cumbia also relies on a strong sense of community among performers. Young musicians learn by watching seasoned veterans, gradually earning the right to join the circle. Mistakes are not hidden or feared; they are woven into the performance, keeping every event fresh and emotionally real.

From Village Squares to World Festivals: Cumbia’s Expanding Reach

While local festivals and street parades remain central to the genre’s identity, the past half-century has seen Cumbia step onto international stages. In 1961, Lucho Bermúdez and his orchestra dazzled crowds at Mexico City’s Palacio de Bellas Artes, marking a turning point for Cumbia abroad. During the 1970s and 1980s, touring artists brought the sound to Argentina, Peru, and beyond, where it was reinterpreted by groups like Los Mirlos and Los Ángeles Azules.

These global exchanges transformed performance styles. Argentinian bands packed large stadiums, replacing flutes with electric guitars and rock drum kits without sacrificing the danceable pulse. Meanwhile, in Peru, so-called Cumbia Amazónica blended psychedelic organ sounds into live sets, sometimes lasting for hours. Each region added something distinct to live performance, even as the essential participatory spirit of the genre persisted.

Festivals have likewise grown in scope and influence. Today, massive gatherings like Mexico’s Cumbia Village Festival bring together performers from across the Americas, drawing thousands of revelers who come expressly to dance, learn, and celebrate the tradition’s diversity. Even in Europe, Cumbia nights in cities like Berlin and Madrid attract crossover audiences, proving that its performance magic is truly borderless.

Technology and the New Era: Broadcasting Cumbia’s Pulse

As radio and television spread in the mid-20th century, Cumbia performances found their way into millions of living rooms. National contests rewarded the best bands and dancers, while Discos Fuentes, Colombia’s legendary record label, captured legendary performances for commercial release. These broadcasts gave many future stars their first taste of national fame and allowed rural traditions to leap into modern pop culture.

With the rise of digital media, contemporary artists now stream Cumbia festivals live on social networking platforms, shrinking the distance between traditional roots and global fans. Virtual collaboration has become commonplace, with musicians from Mexico, Colombia, and Chile improvising together in real time online. The universal access of technology ensures that Cumbia performance keeps evolving—its dynamic, joyful energy transmitted across continents, cultures, and generations.

The energy of live Cumbia is always shaped by the setting, the crowd, and the shifting world around it. New technologies and international collaborations only make the tradition more vibrant. Wherever a drum is struck, a skirt is swirled, or a melody echoes, the communal performance spirit of Cumbia will continue to surprise and unite people—a promise passed on, night after night, in music and movement.

River Journeys and Urban Crossroads: Cumbia’s Changing Face Across Time

Echoes from the Riverbanks: Early Seeds of Transformation

To trace the journey of Cumbia’s evolution, you need to go back to the humid riverbanks and fishing villages of Colombia’s Caribbean coast. In the years before the twentieth century, cumbia was a regional phenomenon passed on orally, thriving in rural communities where life unfolded to the steady pulse of drums and the shimmer of flutes. Yet, even in these humble beginnings, change was already taking root.

As river trade intensified in the late 1800s, small towns like El Banco and San Basilio de Palenque found themselves increasingly connected to neighboring cities. Traveling musicians—known locally as “juglares”—carried their gritty, joyful sound from hamlet to village, picking up influences as they went. Each port and crossroads injected new flavors into cumbia’s DNA. Indigenous flutes might share space with Spanish guitars, while African-inspired hand drums merged with European-style harmonies. These early musical encounters built a foundation for the stylistic leaps the genre would soon take.

From Rural Ritual to Urban Identity: Cumbia’s Migration

With the dawn of the twentieth century, larger cities along the Caribbean—most notably Barranquilla and Cartagena—emerged as cultural melting pots. Internal migration from rural to urban areas brought musicians and dancers in search of new opportunities. In this bustling atmosphere, cumbia transitioned from a localized folk practice into a city-wide, and soon national, phenomenon.

Bars and social clubs sprang up as gathering spaces for both working-class and elite crowds. Radio stations like La Voz de la Costa began broadcasting cumbia in the 1940s, reaching listeners far beyond the traditional festival circuit. Recordings by pioneering orchestras, such as Lucho Bermúdez y su Orquesta, remade the music for larger ensembles. They replaced traditional gaitas with clarinets and added elements from jazz and Cuban music, crafting a vibrant “cumbia de salón” that appealed to urban audiences. Moreover, their arrangements placed cumbia alongside international genres at dance halls, forever shifting its course from rural celebration to cosmopolitan chic.

Orchestral Makeovers and Recording Revolution: The Sound of Change

The late 1940s and 1950s saw a seismic shift in how cumbia was composed, performed, and consumed. The spread of shellac records and the rise of the Colombian recording industry reshaped the genre in profound ways. Studios such as Discos Fuentes and Sonolux in Medellín became crucial players, drawing regional talent and giving cumbia a broader platform.

Producers encouraged bandleaders to blend traditional elements with contemporary instruments—trumpets, saxophones, electric guitars, and later, synthesizers. Legendary figures like Aniceto Molina, Andrés Landero, and Los Corraleros de Majagual harnessed the power of the studio to create new textures and experiment with forms. Landero, known as the “King of Cumbia Sabanera,” transformed rural cumbia with his unique accordion-driven style, creating timeless tracks like La Pava Congona. These innovations didn’t erase cumbia’s rural soul; instead, they expanded its expressive possibilities and made it a bridge between past and present.

Concert tours, radio play, and telenovelas further spread cumbia’s popularity throughout Colombia and into neighboring Venezuela, Peru, and Ecuador. The music’s adaptability became its greatest strength. Urban youth, rural workers, and elite partygoers alike found something to love in cumbia’s evolving vocabulary.

Cumbia Without Borders: Crossroads of Latin America

By the 1960s, cumbia was crossing language and national borders at a remarkable pace. Migrating Colombians brought their music to Panama, Mexico, and Argentina, assimilating new rhythms, stories, and instruments with each move. Radio and vinyl records played a key role, transmitting hits from major Colombian acts to dance parties as far north as Monterrey and as far south as Buenos Aires.

Local musicians didn’t just imitate Colombian cumbia—they transformed it. In Mexico, Rafael de Paz and Tony Camargo reimagined cumbia using brass bands, giving birth to “cumbia mexicana,” while groups like Los Ángeles Azules added lush orchestration and vocal harmonies. In Argentina, cumbia combined with local dance styles to produce “cumbia villera,” marked by biting lyrics and prominent electronic keyboards.

Parallel transformations happened in Peru, where bands such as Los Mirlos and Juaneco y su Combo created “cumbia amazónica,” layering the style with psychedelic guitar lines and influences from Amazonian folklore. These adaptations weren’t subtle. They redefined how cumbia sounded, looked, and felt in each new setting, reflecting local realities and aspirations.

Technology, Migration, and Mass Media: Cumbia in the Modern Age

The technological leaps of the late 20th century—cassette tapes, affordable keyboards, and later digital sampling—fueled the next generation of cumbia innovation. Pirated tapes circulated cumbia to remote mountain towns and urban shantytowns, creating a sense of belonging for migrants far from home.

As cities exploded and mass media redefined how people discovered music, cumbia adapted to new urban landscapes. From the vibrant sound systems (“picós”) of Colombia’s Caribbean coast to Mexico’s iconic sonideros (mobile DJs), the music took on electronic textures and urban slang. Producers like Celso Piña in Mexico became key architects of this digital revolution, blending traditional cumbia rhythms with hip-hop, reggae, and even punk.

Hip-hop collectives, street dancers, and remix artists further reworked cumbia during the 2000s and 2010s. With affordable music software, bedroom producers across Latin America and overseas reshuffled old cumbia classics, launching viral “cumbia digital” tracks. Groups such as Dengue Dengue Dengue in Peru wielded electronic beats, psychedelic visuals, and global collaborations, proving that cumbia’s mutability was both its heritage and its future.

Cumbia’s Global Conversation: From Local Legend to World Soundtrack

By the early 21st century, cumbia was no longer just a regional symbol; it had become a musical language spoken across the planet. In Europe and North America, new fans discovered cumbia through world music festivals, online sharing, and collaborations with electronic artists. DJs in Berlin, London, and New York spun cumbia remixes to cosmopolitan crowds, drawn by its infectious groove and transnational spirit.

Moreover, cumbia served as a platform for new narratives—queer identity, migration stories, and visions of social justice. In Argentina and Chile, collectives integrated feminist messages and Indigenous heritage into their lyrics and performances, using cumbia’s vast reach to amplify new voices.

Although some purists worried about the “dilution” of tradition, cumbia’s living history proves its ability to absorb and reinterpret influences has always been at its core. This genre thrives on dialogue—between past and present, home and abroad, the analog and the digital.

As cumbia continues to evolve in social media playlists and backyard parties from Bogotá to Brooklyn, it stays true to its origins as music of inclusion, connection, and constant reinvention. This spirit of adaptation, fed by migration, technology, and cultural exchange, promises that cumbia’s story is far from over. Every new setting, every new artist, and every new collaboration adds to cumbia’s unfinished symphony—one that will keep echoing wherever dancers gather and drumbeats call.

Echoes That Never Fade: Cumbia’s Enduring Mark on Music and Culture

A Soundtrack for Generations: Passing Down the Pulse

Every corner of Latin America, from remote Andean villages to massive city squares, pulses with the echoes of Cumbia. Its distinct rhythm—marked by the hypnotic interplay of drums, flutes, and shakers—has provided a steady heartbeat across shifts in politics, migration, and cultural tides. What began as a regional expression along Colombia’s Caribbean shores has become a musical inheritance, shared across nations and generations.

Unlike many genres that fade when trends shift, Cumbia has experienced seamless continuity thanks to oral tradition and a deep connection to family life. Grandparents teach grandchildren the steps in living rooms, while teenagers remix classic riddims on their phones. This transfer isn’t just about notes and lyrics—it’s about values, memory, and a sense of home. In Colombia’s Atlántico region, for instance, elders still recall learning cumbia at riverside celebrations, while urban youth see in it a link to ancestry and national pride.

Moreover, courtship rituals and carnival traditions associated with Cumbia persist, especially during major festivals in Colombia, Mexico, and Argentina. These events aren’t throwbacks, but living rituals that reinforce community identity and make Cumbia feel at once ancient and perpetually new.

From Coastal Dance to Continental Anthem: The Spread Through Latin America

The extraordinary reach of Cumbia owes as much to migration and technological change as to the genre’s irresistible groove. The 1940s and 1950s saw urban centers like Barranquilla become hotbeds for musical experimentation, where local artists began to record and broadcast their sounds. The arrival of vinyl records and AM radio accelerated this spread, projecting the infectious rhythms far beyond Colombia’s borders.

In the late 1950s, bands such as Los Gaiteros de San Jacinto and Lucho Bermúdez y su Orquesta produced recordings that became regional hits. Cumbia found eager audiences in Panama, Peru, Argentina, and beyond, adapting to local tastes along the way. In each place, musicians infused their own instruments, languages, and stories, creating variations like cumbia villera in Argentina, chicha in Peru, and cumbia sonidera in Mexico. Every new branch preserved the core pulse but layered on fresh influences, making Cumbia not just a Colombian treasure, but a Latin American one.

This musical journey was never a one-way street. As Cumbia traveled, it also shaped and was shaped by other regional genres. For example, in Mexico, orchestras such as Aniceto Molina and groups like La Sonora Dinamita helped blend cumbia with salsa and norteña, giving rise to an entire new style that now dominates dance halls from Monterrey to Los Angeles.

Innovation and Fusion: Cumbia’s Endless Reinvention

Far from being frozen in the past, Cumbia thrives on innovation. Over the decades, artists and producers have folded in electric guitars, synthesizers, and digital effects, pushing the genre into new territory. The psychedelic cumbia of Peru’s 1970s “chicha” scene brought distorted guitars into the mix, as bands like Los Mirlos and Los Destellos integrated urban and Amazonian sounds. In Mexico City, post-1980s “sonideros”—mobile DJ collectives—spun vinyl mixes at block parties, incorporating everything from techno beats to reggae influences.

More recently, younger musicians have reimagined Cumbia for the global stage. Electronic acts such as Bomba Estéreo and producers like Chancha Vía Circuito blend traditional rhythms with bass-heavy electronica, making Cumbia a staple of international music festivals. These artists draw passionate followings in Europe, North America, and Asia, proving that the genre can evolve without losing its local roots.

Sampling and remix culture has added another layer. From underground clubs in Buenos Aires to trendy bars in Berlin, DJs drop Cumbia-infused tracks, introducing the style to listeners whose parents may never have dreamed of dancing to its beat. The genre’s open structure means it is always ready for new stories, new technologies, and new dancers.

Political Voices and Social Movements: Cumbia as Protest and Expression

Historically, Cumbia has not only been a soundtrack for celebration, but also a vehicle for political and social commentary. In Colombia, musicians have long woven narratives about migration, love, and hardship into their lyrics. Songs like La Piragua by Guillermo Cubillos recount the struggles and dreams of rural life, resonating in times of upheaval.

In the 1970s and 80s, as Cumbia migrated across class and national boundaries, it became a voice for marginalized communities. In Peru, the psychedelic “chicha” variant rose with the influx of Andean migrants into Lima, blending rural and urban sensibilities while speaking to themes of displacement and hope. Meanwhile, in Argentina, the rise of cumbia villera was bound up with social critique—bands like Damas Gratis gave voice to the working class with gritty, streetwise lyrics.

This pattern has continued into the present. Activist musicians and grassroots collectives use Cumbia as a tool to address contemporary issues like violence, inequality, and cultural resilience. During the COVID-19 pandemic, digital “cumbia parties” became online hubs for solidarity, raising funds for communities in need while keeping spirits high through shared music.

Cumbia’s Global Leap: Crossing Oceans and Finding New Homes

By the late 20th century, Cumbia had begun to find enthusiastic listeners outside Latin America. Migration played a role, as Latinx diaspora communities in cities such as New York, Los Angeles, and Paris brought their dances and musical customs with them. Local bands would reinterpret Cumbia to suit their new contexts—infusing lyrics with references to new neighborhoods or weaving in the sounds of hip hop, jazz, and funk.

International collaborations further fueled the spread. When French producer Quantic teamed up with Colombia’s Combo Bárbaro, the result was a multilayered sound that brought Cumbia to European hangouts and playlists. In 2010, the compilation Cumbia Cumbia 1 & 2—reissued globally—introduced a vast new audience to forgotten Colombian gems.

Festivals across Europe, the United States, and Australia now regularly include Cumbia acts, signaling its arrival as a truly global music. Online platforms like SoundCloud and YouTube allow new generations across continents to discover, remix, and reinterpret classic Cumbia tracks at the click of a button, ensuring the genre’s pulse resonates in countless languages and contexts.

Looking Forward: Cumbia’s Future in a Changing World

Throughout every transformation, Cumbia has proven that its greatest strength lies in adaptability and collective joy. Whether moving feet on ancestral riverbanks or lighting up futuristic festival stages, its beat remains a bridge—connecting past and present, village and metropolis, memory and invention.

As technology continues to shrink distances and blur boundaries, Cumbia stands ready to embrace future generations. Its history of reinvention suggests that wherever people gather to dance, celebrate, or resist, the unmistakable rhythm of Cumbia will always have a place in the world’s musical conversation.