Rhythms Born in Kingston: Dancehall’s Bold Pulse

Emerging in late 1970s Jamaica, Dancehall electrified music with its infectious rhythms, digital beats, and lyrical storytelling. Pioneers like Yellowman and Sister Nancy made dancehall global, reshaping club culture everywhere.

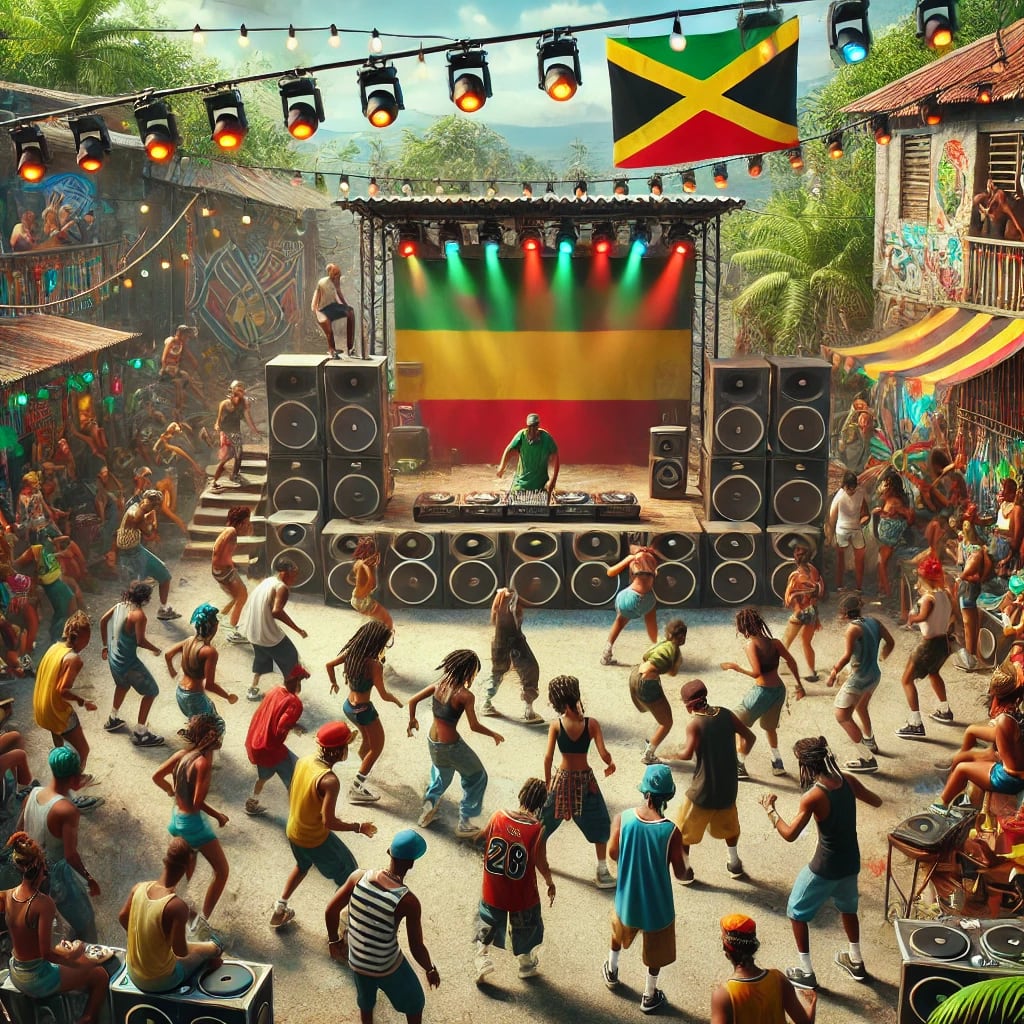

Vibrant Streets and Sound Systems: The Roots of Dancehall’s Revolution

Turning Up the Volume: Jamaica in the 1970s

The late 1970s in Kingston was a city alive with creative energy and a relentless drive for expression. In these bustling neighborhoods, social and economic pressures mingled with vibrant youth culture. Parties spilled into the streets, transforming everyday spaces into makeshift dance arenas known as “dancehalls.” Against a backdrop of political uncertainty and economic hardship, Jamaicans didn’t just seek escape—they demanded it, carving out spaces for music and movement. The demand for louder, more rhythmic, and energetic music was almost palpable in the air.

During this era, reggae was already a significant force in Jamaican music, carrying messages of struggle and hope worldwide. However, many younger listeners wanted something fresher—music less tied to spirituality or politics and more about real-life pleasures, humor, bravado, and social commentary. The sound systems, massive speaker setups operated by neighborhood entrepreneurs like King Tubby and Prince Jammy, responded. They played new styles that echoed community life, blending bass-heavy rhythms with catchy, repetitive hooks. These open-air events were more than entertainment; they were social epicenters, places where locals could experience the latest music before it hit the radio.

From Roots Reggae to Dancehall: A Genre Evolves

The musical seeds of Dancehall did not grow in isolation. Instead, they emerged from the deep roots of the reggae scene, evolving as producers and artists sought new sonic directions. Where roots reggae favored organic instruments and smooth, hypnotic grooves, emerging Dancehall tracks began introducing greater rhythmic drive and emphasizing electronic experimentation.

One crucial shift was the move toward “riddims”—instrumental backing tracks designed for vocal improvisation and crowd response. Producers like Coxsone Dodd and Linval Thompson developed rhythm tracks that multiple artists could voice over, adding their own lyrics and personal style. This flexibility allowed for a flurry of creativity, with singers and deejays delivering witty, brash, or socially conscious lyrics that resonated with Kingston’s restless youth.

By the late 1970s, early Dancehall pioneers like U-Roy and Big Youth were already toasting—an early form of rapping—over instrumental breaks in reggae songs. Their rapid-fire vocal styles set the stage for dedicated Dancehall deejays, elevating crowd banter and storytelling into headline acts. This era saw sounds shift from laid-back rhythm guitars to punchy, syncopated drum patterns, and hard-hitting bass lines that energized dance floors.

The Sound System Culture: Building Community and Competition

Sound systems were the heartbeat of Dancehall’s emergence, driving not only sonic innovation but also intense local rivalries. Each crew fought for recognition, investing in ever-larger speakers and exclusive records. Partygoers were lured with the promise of the freshest “dub plates”—unique versions of songs personalized with the crowd’s name or rival crew insults. Winning sound clashes, often fierce musical battles between systems, meant more than bragging rights; it drew crowds, guaranteed repeat business, and cemented reputations.

Moreover, these sound systems democratized music. Unlike formal concerts, dancehalls were accessible and affordable. Anyone could attend, request their favorite tune, or even step up to the microphone if the atmosphere allowed. This inclusivity turned dancehalls into cultural crossroads where styles, stories, and slang traveled across class and neighborhood borders. Newcomers observed and learned from seasoned deejays, feeding a constant flow of fresh talent into the scene.

Radio exposure for Dancehall was rare at first—conservative stations often dismissed the genre’s streetwise rhythms as too raw. However, the relentless push from local parties and word-of-mouth popularity forced wider acceptance. Before long, Kingston’s hottest sound system hits trickled into recording studios and, eventually, onto airwaves.

Digital Shockwaves: Technology Reshapes the Beat

A major turning point in Dancehall’s rise came with the introduction of affordable digital synthesizers and drum machines in the early 1980s. While recording studios in Europe and the United States had experimented with electronic sounds for years, most Jamaican producers had relied on live bands and analog recording.

Everything changed with Wayne Smith’s seminal 1985 hit Under Mi Sleng Teng. Legendary producer King Jammy crafted this track using a preset rhythm from a Casio MT-40 keyboard, marking the dawn of the “digital riddim” era. This pioneering use of digital sampling sent shockwaves through the scene and beyond. Suddenly, music production became faster, cheaper, and more accessible. Producers cranked out dozens of new riddims, and artists could record tracks in a fraction of the time and cost previously required.

Digital instrumentation brought a sharper, more aggressive sound. Drum machines produced cleaner, crisper beats; synthesized bass lines vibrated through towering speakers with eye-watering force. This new era redefined the genre’s aesthetic and accessibility. It unlocked a wave of creative opportunity, allowing producers and artists to experiment with entirely new textures and rhythmic possibilities.

Established stars like Yellowman smoothly transitioned into this digital realm, while fresh faces like Shabba Ranks and Ninja Man embraced the changes, crafting hits that exploded onto both local and international charts. The digital revolution made Dancehall even more immediate and relentless, constantly evolving on the streets, in the studio, and across the globe.

Voices of the People: Social Commentary and Identity

Although Dancehall’s party beats are legendary, its historical roots are deeply intertwined with Jamaica’s social realities. The genre’s unsparing lyrics captured the day-to-day experiences of its audience: hardship, ambition, love, sexual freedom, and political frustration. Notably, Dancehall offered a megaphone for those whose stories often went unheard in mainstream society.

Songs addressed everything from neighborhood conflicts to relationships, always with a blend of humor, boldness, and sometimes controversy. Artists like Sister Nancy and Papa San gave voice to the aspirations and anxieties of Jamaica’s working class. The dancehall itself served as a public forum, a place where music became both entertainment and a tool for social discussion.

The genre’s gritty honesty sometimes attracted criticism, with debates about lyrical content and representation. However, to its devoted fans, Dancehall provided rare authenticity—a lived-in reflection of Jamaican life, unfiltered and unpretentious.

A Launchpad to the World: Dancehall Goes Global

As Dancehall matured, it crossed oceans, finding enthusiastic audiences in the UK, North America, and Africa. Migrant communities carried cassettes and vinyl across borders, planting seeds for international fusion. London’s Notting Hill Carnival became a second home for sound systems, while New York clubs pulsated with the genre’s infectious beats. By the late 1980s and early 1990s, Dancehall’s pulse throbbed from Tokyo to Toronto, inspiring new musical hybrids like reggaeton and influencing pop, hip-hop, and electronic music.

Though its foundation was laid in the neighborhoods of Kingston, Dancehall’s voice continued to adapt, echoing in languages and cultures far from its island home. Today, the evolution of Dancehall—sparked by restless innovation, community competition, and technological breakthroughs—remains a testament to music’s power to cross boundaries and energize each new generation.

With every new artist, production style, or dance trend, the genre’s journey moves forward—a rhythmic revolution still unfolding and refusing to stand still.

The Sound of the Streets: Dancehall’s Electrifying Musical DNA

Pulsing Rhythms and the Role of the Riddim

The heart of dancehall music lies in the relentless pulse of its rhythms, driven by the concept of the riddim. In dancehall, a riddim is more than just a backing track—it’s a repeating instrumental groove built from hypnotic drum and bass patterns, sometimes layered with keyboards and digital effects. Unlike the slower, rootsier beats of classic reggae, dancehall riddims are usually faster, sharper, and more energetic, perfectly primed for late-night parties and open-air dances. The riddim functions almost like a communal canvas, allowing dozens of different vocalists—called deejays or singjays—to create their own unique songs over the same backing, lending a sense of unity and competition to the genre.

What sets dancehall apart is the innovation in how these rhythms are produced. Early pioneers like King Jammy unleashed the digital revolution on Jamaican music in the mid-1980s with the introduction of the iconic Sleng Teng riddim. Created using a simple Casio keyboard, Sleng Teng marked one of the first fully digital riddims, giving birth to a new sound marked by electronic drums, synthetic basslines, and a crisp, biting intensity. The impact was immediate—record producers and deejays scrambled to create their own digital riddims, resulting in a wild explosion of creativity and fierce competition across Kingston’s vibrant music scene.

This emphasis on riddim culture shaped dancehall’s structure in a way that’s almost unique in global popular music. At any big street party, you might hear a dozen tracks back-to-back, each using the same underlying groove, but transformed by individual vocal styles. This system encourages variety, freestyle lyricism, and a constant stream of new releases, all built around the ever-evolving pulse of the streets.

Vocals as Verbal Acrobatics: Toasting, Chanting, and the Singjay Style

Dancehall vocals diverge sharply from the smooth, melodic harmonies of traditional reggae. Instead, they borrow from Jamaica’s “toasting” tradition—an art form rooted in the spoken word, where deejays deliver rhythmic, quick-witted lyrics that pulse with the beat. Sometimes compared to rapping, toasting is all about rhythm, attitude, and on-the-spot creativity. Early leaders like Yellowman, with his irreverent humor and dazzling wordplay, brought toasting into the mainstream, making it a cornerstone of the dancehall sound.

The style of vocal delivery in dancehall is flexible and fiercely competitive. Some performers—known as singjays—blend raw, melodic singing with rapid-fire chatting, switching between hooks and verses without missing a beat. Sister Nancy, for example, combined confident vocals and staccato phrasing in Bam Bam, a track that remains influential worldwide. This hybrid style allows for endless experimentation with phrasing, storytelling, and attitude—one moment gritty and raw, the next smooth and catchy.

Lyrical content in dancehall balances razor-sharp wit with direct, often controversial commentary on daily life, love, politics, and street culture. Dancehall artists have never shied away from tackling difficult topics, sometimes courting controversy with explicit language and unfiltered stories. The vividness and immediacy of these lyrics create an atmosphere that feels urgent, intimate, and utterly real—reflecting both the hardships and the hopes of Kingston’s neighborhoods.

Digital Production: Drum Machines and Sound System Science

A defining feature of dancehall music is its embrace of technology. Even during its early years, dancehall producers eagerly adopted new tools, making digital production techniques central to the genre’s evolution. Drum machines like the Roland TR-808 and digital synthesizers replaced traditional live bands, allowing producers to create new riddims at lightning speed and with unprecedented sonic variety.

The role of the sound system in shaping dancehall’s musical characteristics cannot be overstated. Massive speaker stacks and custom-built amplifiers transformed backyards and parking lots into throbbing dancefloors. Producers began favoring bass-heavy mixes and crisp, high-pitched snares designed to cut through the din of street parties. Engineers like King Tubby and Scientist became legends for their ability to manipulate sound, using echo, reverb, and delay to add drama and excitement to every track.

Moreover, producers developed a playful relationship with technology through innovative use of sampling and effects. Borrowing from the global rise of hip hop and electronic music in the 1980s, dancehall tracks often feature snippets of radio broadcasts, sirens, and street sounds, blending local flavor with a futuristic edge. This approach gave dancehall a sonic identity that was at once deeply rooted in Jamaican culture and unmistakably modern.

Battle-Cry Energy and the Dance Floor Connection

The dancehall sound is built for movement—every element, from the insistent drumming to the bold lyrics, is designed to get bodies moving. Dancehall parties, whether in a Kingston yard or a London club, thrive on an electricity that comes from the music’s direct connection to the dance floor. Unlike studio-centric genres, dancehall is shaped in real time by dancers and audiences, whose cheers, movements, and requests can influence what deejays play or even what an artist improvises on the mic.

Dance moves have become a critical part of the musical landscape. With each new riddim or hit track, fresh dance crazes burst onto the scene, often going viral before “viral” even existed. Moves like the Bogle and the Dutty Wine showcase dancehall’s capacity to fuel trends, uniting fans on the dance floor and far beyond. This participatory nature means the music responds rapidly to changes in style and taste, ensuring that it always feels new and alive.

Competition is another vital ingredient. Friendly musical clashes between sound system crews, known as “sound clashes,” push producers and deejays to outdo each other, upping the energy with bigger bass, sharper lyrics, and more inventive beats. These battles drive constant experimentation and have shaped the relentless innovation that defines the genre.

Local Roots, Global Reach: Dancehall’s Expanding Sonic Frontier

While dancehall’s core musical attributes were developed in the intense atmosphere of 1980s Kingston, its influence quickly spread far beyond Jamaica’s shores. As Jamaican immigrations took root in cities like London, Toronto, and New York, the sound systems, riddims, and performance styles of dancehall reshaped urban music scenes around the world.

International artists began to blend dancehall’s blueprint with local genres. UK “bashment,” African afrobeats, and American hip hop all absorbed elements from dancehall’s rhythms, vocal style, and digital production. Producers from outside Jamaica took up the riddim concept, creating multilingual adaptations and genre-crossing collaborations. Hits by global stars—like Sean Paul and Shabba Ranks—brought dancehall slang, groove, and swagger to mainstream radio everywhere, proving that this once-underground sound had become a worldwide phenomenon.

Yet, even as dancehall evolves, its musical characteristics remain rooted in that early Kingston DNA: driving riddims, a love of technology, inventive lyricism, and a deep, unbreakable bond with the spirit of the dance floor. Whether echoing from a street party in Portmore or blasting out of speakers in Tokyo, dancehall’s electrifying sound continues to spark movement, creativity, and cultural exchange, promising fresh innovations with every new beat.

From Classic Bashment to Global Waves: Dancehall’s Ever-Changing Faces

Digital Explosions: The Birth and Rise of Ragga

When the dancehall scene burst onto the Jamaican airwaves in the late 1970s, its sound was firmly anchored in live instruments and analog recording. By the mid-1980s, however, something seismic happened. The digital revolution arrived, rewriting the genre’s DNA almost overnight. This was the dawn of ragga—a game-changer for both Jamaican music and global pop culture.

Ragga, short for “ragamuffin,” marked dancehall’s bold leap into the digital age. It all started with the Sleng Teng riddim, crafted by King Jammy in 1985 using a simple preset from a Casio MT-40 keyboard. The beat was synthetic, minimal, and entirely electronic. Suddenly, producers realized they could generate catchy tracks quickly, at a much lower cost, without needing a full band. The genre exploded with new energy. Artists like Wayne Smith, with Under Me Sleng Teng, and later Shabba Ranks and Admiral Bailey, rode this wave, delivering rapid-fire lyrics over the infectious beats. Compared to earlier dancehall, which still sounded somewhat like a stripped-down, harder-edged reggae, ragga was harder, colder, and more futuristic.

Europe, Africa, and North America all began embracing these new riddims, with European producers such as Bobby Konders and UK-based labels like Fashion Records crafting their own digital interpretations. What made ragga different wasn’t just its production technology. The vocal style evolved too, featuring more aggressive “toasting” and machine-gun flows, shaped for crowded dancefloors rather than spiritual uplift. Ragga’s global influence would soon spark new hybrid genres, influencing everything from UK jungle and grime to Latin reggaeton.

Bashment Parties and The Rise of Hardcore Dancehall

As the digital sound took hold, a new era called “bashment” emerged—shorthand for wild, over-the-top parties dominated by pounding riddims, fierce competition, and daring dancing. Here, dancehall shed any lingering ties to reggae’s relaxed, conscious roots. Instead, hardcore dancehall—sometimes called simply “new school”—dominated the late 1980s and 1990s.

Hardcore dancehall is defined by its relentless energy, provocative lyrics, and a focus on the raw realities of urban life. Bounty Killer, Beenie Man, and Lady Saw became the new icons, wielding fast-paced lyricism over thunderous, bass-heavy productions. The lyrics spoke directly to young Jamaicans, covering topics from love and sex to street survival, social injustice, police violence, and nightlife escapades. The performances grew more theatrical, with sound clashes (competitive battles between deejays and sound systems) becoming major cultural events.

Throughout Kingston, neighborhoods organized raucous open-air celebrations, elevating bashment to a powerful form of self-expression and escape. Dancers created new moves, each meant to go viral before the internet even existed. Tracks like Beenie Man’s Girls Dem Sugar and Lady Saw’s Sycamore Tree captured both the boldness and vulnerability of the genre. By the 1990s, harder and ever more provocative forms dominated the dancefloor—a testament to the genre’s constant thirst for reinvention.

Lovers Rock: Softening the Edges

Despite its tough reputation, dancehall has always had a softer, melodic side. Lovers rock is a subgenre that blossomed in Jamaica and especially among the UK’s Caribbean communities. Starting in the late 1970s and surging in the 1980s, lovers rock offered a gentler, romantic sound—lush, soulful melodies layered over midtempo riddims that retained dancehall’s groove but swapped aggression for intimacy.

Janet Kay, Carroll Thompson, and later Beres Hammond became touchstones for this style, blending the rhythmic foundation of dancehall with elements of American soul and British pop. The lyrics focused on romance, heartbreak, and emotional storytelling. While not as dominant in Jamaican parties, lovers rock captivated radio listeners and club-goers across London, Birmingham, and beyond, helping carve out a unique Caribbean-British identity. The smooth production and universal themes created a bridge between hardcore dancehall and mainstream pop, showing another side of the genre’s versatility.

Dancehall Goes Global: Regional Hybrids and International Innovations

As the 1990s rolled into the new millennium, the world’s fascination with dancehall exploded in unexpected directions. Localized scenes flourished on faraway continents, each putting their spin on the Jamaican blueprint and giving rise to bold hybrid forms.

In the UK, dancehall’s militant rhythms fused with British electronic music to help birth jungle and garage. Artists like General Levy and production houses such as Shut Up and Dance sampled ragga vocals and riddims, speeding them up to match the breakneck pace of UK dance clubs. Across the Atlantic, hip-hop artists including The Notorious B.I.G. and Sean Paul pulled heavily from dancehall to shape new club anthems. In Japan, a vibrant dancehall culture emerged, with artists such as Mighty Crown and Pushim adopting patois and crafting their own signature sound system battles.

Perhaps the most prominent global fusion lies in the rise of reggaeton in Latin America. Puerto Rican producers like DJ Playero and artists like Daddy Yankee drew directly from Jamaican dancehall’s digital beats and the art of toasting, merging those influences with Spanish-language rap and local rhythms like dembow. The result—a worldwide phenomenon that fills stadiums and dominates streaming charts from Bogotá to Barcelona. Meanwhile, African artists and producers, from Ghana’s Shatta Wale to Nigeria’s Patoranking, reinterpret dancehall through Afrobeats, blending Caribbean swagger with African melodies and rhythms. This mutual influence has led to entirely new sounds, with African dancehall stars headlining major festivals and collaborating with their Jamaican counterparts.

Conscious Dancehall: Voices of Resistance and Change

While hardcore and party-themed dancehall grabbed the spotlight, another current has always run through the music: a stream of deeply conscious, socially aware tracks. This “conscious dancehall” pushes back against stereotypes, driven by artists with messages about upliftment, unity, and resistance to injustice.

Figures like Buju Banton and Sizzla champion this approach. Their songs mix the irresistible groove of modern dancehall with lyrics reflecting on spirituality, political violence, and solutions to social division. Albums such as ’Til Shiloh by Buju Banton and Da Real Thing by Sizzla became anthems for the “roots revival” within dancehall, inspiring listeners in Jamaica and throughout the Caribbean diaspora. This strand of dancehall demonstrates the genre’s depth—proving it’s not just a soundtrack for the party, but a platform for meaningful dialogue and cultural healing.

Genre Crossroads: Evolution Continues

Every subgenre of dancehall reveals a moment in time—a snapshot of Jamaican society and its countless global echoes. From the raw experimentation of early digital ragga to the genre-mixing creativity of today’s Afro-dancehall and Latin pop, dancehall thrives on change. Its subgenres are not fixed boxes, but stages in a conversation—between generations, continents, and communities who keep reinventing what dancehall can mean.

Today’s hits might draw equally from Tokyo, London, Lagos, or New York, but the energy remains unmistakably Jamaican. Dancehall subgenres tell a story not just of musical innovation, but of cultural risk-taking, global mixing, and a never-ending hunger to move people—on the dancefloor and beyond. That story is still unfolding, with new voices ready to push the boundaries and turn up the volume all over again.

Voices That Shaped the Dance: Icons, Innovators, and Legendary Tracks

Stars from the Sound System: Dancehall’s Founding Visionaries

No story about dancehall can begin without honoring the architects who turned Kingston’s street corners into launching pads for a worldwide movement. Yellowman stands tall as one of the most influential early figures. Unmistakable for his distinctive voice and daring lyrics, he brought a new kind of charisma to the scene in the early 1980s. His hit songs like Zungguzungguguzungguzeng didn’t just electrify parties; they set the template for witty, boastful wordplay and the playful, risqué energy that became a dancehall signature.

Another foundational voice, Josey Wales, brought the dancehall crowd closer with his clear delivery and conversational style. Drawing his nickname from the Clint Eastwood character, Josey’s songs such as Undercover Lover and Leggo Mi Hand established the “deejay chat”—quick, rhythmic speech layered over pounding riddims. This vocal approach, carried out in the heat of live performances, emphasized storytelling rooted in everyday struggles and victories.

While vocalists got the spotlight, visionaries behind the mixing desk also shaped dancehall’s early direction. King Jammy—a true studio alchemist—was already a legendary dub engineer when he became a kingmaker in digital dancehall. It was Jammy’s work with Wayne Smith on the song Under Me Sleng Teng that set off shockwaves in 1985: this was the birth moment of digital riddims, suddenly making dancehall sharper, more futuristic, and accessible to a wider generation hungry for modern sounds.

Pioneers of the Digital Sound: The Rise of Ragga and Beyond

The arrival of fully digital production changed Jamaican music’s DNA and made entirely new stars possible. Shabba Ranks, with his gravelly baritone and rapid-fire style, quickly became a symbol of the new ragga sound. His major hits—Trailer Load a Girls, Ting-A-Ling, and the Grammy-winning Mr. Loverman—weren’t just dance anthems in Kingston. These tracks made Shabba an international phenomenon, spreading ragga’s bold flavor to club scenes from New York to London.

Female voices also claimed the microphone with fearless confidence. Sister Nancy was a trailblazer, dropping Bam Bam in 1982—a song whose infectious hook and smart, rebellious lyrics echoed through dancehalls and decades of later sampling. Her style was unmistakably her own: playful yet assertive, bridging the gap between party music and pointed social commentary. As one of the first prominent female deejays, Sister Nancy opened doors wide for later generations of dancehall queens.

Meanwhile, Admiral Bailey and Chaka Demus each stamped their identity on the post-Sleng Teng era, crafting hits that were both witty and provocative. Punanny by Admiral Bailey, with its minimalist digital backing, is a classic of 1980s dancehall—fun, bold, and impossible not to move to. Chaka Demus, often teaming up with Pliers, introduced a melodic twist to vocals, helping songs like Murder She Wrote cross over into mainstream pop charts.

Riddims That Changed Everything: The Heartbeats of Dancehall

If dancehall is a city, the riddim is its ever-pulsing heartbeat—constantly evolving but instantly recognizable on any street corner. The most iconic of them all is the Sleng Teng riddim. Created almost by accident using a preset on a Casio keyboard, its debut in 1985 rewrote the rules of Jamaican music production. Suddenly, artists could record original tracks much faster, and countless performers put their own stamp on the same hypnotic electronic groove.

Other foundational riddims quickly joined the canon. The Stalag riddim, originally crafted by Winston Riley in 1973, exploded in popularity during the digital era, becoming a launching pad for dozens of dancehall hits by multiple artists. Its magnetic, head-nodding bassline can be heard underpinning classics like Ring the Alarm by Tenor Saw—a song that remains essential for understanding both the sound and attitude of dancehall culture.

As the genre progressed, new riddims continued sparking waves of creativity. The Bam Bam riddim, propelled by Sister Nancy’s legendary vocal, proved endlessly versatile, cropping up in club remixes, international reggae festivals, and even hip-hop samples. These instrumental backdrops are not just musical blueprints; they’re gathering places for artists to compete, collaborate, and challenge each other in real time, both on vinyl and on the sound system stage.

International Trailblazers: Dancehall’s Leap to the Global Stage

While local stars like Yellowman and Shabba Ranks powered the genre’s homegrown evolution, a new generation expanded dancehall’s sound far beyond Jamaica. In the 1990s and early 2000s, Sean Paul emerged as a bridge between gritty street culture and the global pop mainstream. His multi-platinum albums like Dutty Rock (2002) and infectious tracks such as Get Busy and Temperature brought dancehall to radio and dancefloors from Tokyo to Paris, all while respecting its homegrown essence.

Another key name was Beenie Man, crowned “King of the Dancehall.” With megahits like Who Am I (Sim Simma) and Girls Dem Sugar, he pushed the genre’s boundaries, blending dancehall braggadocio with catchy hooks. Beenie Man’s collaborations with global stars emphasized dancehall’s adaptability—showing how its core rhythms could mesh with hip-hop, R&B, and pop, without losing their playful bite or streetwise spark.

On the production side, visionaries like Dave Kelly, architect of the game-changing Showtime riddim, helped define the late 1990s and early 2000s dancehall sound. With his forward-thinking approach, Kelly crafted riddims that became instant classics, spawning a new wave of hits for countless artists and ensuring that dancehall’s heartbeat continued to evolve in exciting new directions.

Voices of Resistance: Political, Social, and Cultural Impact

Dancehall’s most powerful tracks haven’t only been about bragging rights and party vibes. Often, its biggest stars have used their platforms for sharp social commentary. Buju Banton’s Untold Stories tackled issues of poverty and injustice with a raw honesty that resonated across generations. Early on, Buju’s contrasting musical persona exemplified dancehall’s layered voice—sometimes celebratory, sometimes deeply critical of the world outside the party.

Lady Saw—unquestionably the “Queen of Dancehall”—challenged male-dominated expectations with her fiery delivery and anthems like Man Is The Least. Her lyrics confronted gender double standards head-on, giving women in the dancehall space new visibility and influence. Lady Saw’s success inspired other female artists to demand the microphone, building a more inclusive genre along the way.

Moreover, dancehall has never shied away from exploring themes of identity and community pride. Songs like Super Cat’s Ghetto Red Hot voiced the spirit and resilience of the urban neighborhoods from which the genre sprang. For listeners far from Jamaica, these tracks carried vivid snapshots of Caribbean experience—offering both a window into local realities and a channel for cross-cultural connection.

New Generations and the Digital Revolution

As the 21st century unfolded, dancehall’s evolution only accelerated. The rise of digital distribution and social media meant new artists could break out globally overnight. Performers like Vybz Kartel, with provocative lyrics and groundbreaking albums like Pon Di Gaza 2.0, found worldwide audiences with viral hits such as Fever—blurring the boundaries between local subculture and global trend.

Popcaan built on this movement, mixing dancehall’s core energy with elements from hip-hop and electronic music, producing international hits like Only Man She Want and collaborating with artists from Europe, Africa, and North America. This new wave of stars shows how dancehall’s spirit of innovation persists. They continuously redefine what the genre can be, reflecting the changing hopes, dreams, and struggles of a new generation of listeners.

Looking at the journey from the raw street parties of Kingston to the glossy international stage, one thing becomes clear: dancehall’s key figures and classic works are not just musical achievements. They’re living, breathing stories—ongoing, adaptable, and forever charged with the energy of the crowd, the riddim, and the world’s dance floors still spinning to their beats.

Studio Alchemy and Street Sound: The Mechanics Behind Dancehall’s Explosive Groove

Riddims in Motion: Building the Dancehall Backbone

At the center of dancehall production stands the riddim—the driving, repetitive instrumental that becomes the pulse of every track. But crafting a riddim in dancehall isn’t just about looping a beat. Producers start with a blend of electronic drum machines and carefully programmed basslines designed for maximum energy. The drum patterns, often influenced by Jamaican mento and American funk, create a tight, syncopated groove that leaves space for bass to rule the low end.

During the early days, before the digital revolution, dancehall riddims were played live by small studio bands. Musicians recorded crisp snare hits, punchy kick drums, and nimble bass guitar lines in legendary Kingston studios. Analog mixing boards, reel-to-reel tape machines, and spring reverbs shaped the sound, giving classic tracks from the 1980s a warm, organic feel.

That aesthetic changed dramatically by the mid-1980s. With the widespread use of digital synths and drum computers like the Casio MT-40 and Yamaha DX7, riddims gained a harder, more mechanical edge. Pioneering producers such as King Jammy led this shift. His Sleng Teng riddim wasn’t just innovative for its catchy melody, but also for its fully digital construction—a revolution that rippled across the globe.

Nowadays, most dancehall tracks skip live instruments altogether. Producers build beats inside computers, tweaking each hi-hat and snare for precision. Software like FL Studio or Logic Pro lets aspiring riddim-makers layer synthetic horns, strings, and effects with dazzling speed. But no matter the tools, the main mission remains: produce a rhythm so infectious, nobody can resist moving.

Vocal Styles and Digital Deejaying: The Evolution of the Voice

While dancehall production centers on the riddim, the vocals—delivered by deejays and singjays—infuse the music with personality. Unlike American rap, which focuses on complex rhyme patterns, dancehall vocals rely on a blend of “chatting” (rhythmic speech) and melody. The style is rooted in the Jamaican “toast,” where deejays hype up crowds with quick, punchy lines at local sound system dances.

Early innovators like Yellowman and Josey Wales used microphones with limited recording technology. Their voices cut through slightly rough mixes, sometimes pronounced with tape hiss or the hum of the street. But the raw edge added to the music’s energy, giving it a sense of immediacy.

As technology advanced, so did vocal processing. By the 1990s, studios began using digital effects—echo, reverb, pitch shifting—to sculpt vocals into almost any shape. Deejays would experiment with layered harmonies, vocal stutters, or artificial doubling, all designed to stand out on crowded dancefloors. In modern productions, artists such as Vybz Kartel and Spice push these effects even further, incorporating Auto-Tune and extreme EQ to shape distinctive sonic personas.

This technical innovation has allowed dancehall to match the demands of radio and clubs everywhere. Recordings are louder and cleaner than ever, while still retaining the swagger and raw charm that have always been the genre’s trademarks.

Sound Systems and Sonic Power: Engineering the Dancefloor Experience

You can’t talk about dancehall’s technical magic without spotlighting the mighty Jamaican sound system. These mobile, custom-built stacks of amplifiers and speakers are both a symbol and a laboratory for dancehall’s development. From Kingston’s inner-city yards to international festivals, sound systems are where technology and musical culture collide.

Building a proper sound system isn’t just about turning up the volume. It’s a form of competitive engineering where crews like Stone Love and Killamanjaro obsess over speaker boxes, amplifier wattage, and selector skill. The goal is simple: achieve earth-shaking bass and crystal-clear highs that command the crowd’s attention.

Selectors—essentially DJs—hunt for exclusive “dubplates,” special versions of popular songs recorded only for their crew. These versions often feature shout-outs or lyrical tweaks, engineered live or in the studio. Selectors drop these rare cuts during “clashes,” where rival sound systems face off in epic battles of volume, skill, and technical creativity.

Dedication to technical detail stretches into the mix itself. Dancehall engineers use techniques pioneered in Jamaican dub music: radical EQ carving, dropouts where only the bass remains, and splashes of echo and delay that bounce off courtyard walls. Sometimes, they even “pull up”—rewind the record at a dramatic moment to replay the crowd’s favorite section, all in real time.

The sound system culture isn’t just about technology; it’s an ongoing experiment in what makes bodies move. Each event is a test bed for acoustics, crowd psychology, and musical intensity, connecting technical decisions directly to real-world energy.

From Reel-to-Reel to Pro Tools: Transforming the Studio Landscape

Technological innovation has always shaped how dancehall is recorded, produced, and shared. In the analog era of the late 1970s, producers worked with hardware limitations—24-track tape machines, manual mixing desks, and outboard effects. Editing meant physically cutting tape and splicing it back together, a painstaking process that demanded both skill and patience.

The 1980s digital explosion, led by studios like Jammy’s and Penthouse, brought revolution. Affordable synthesizers and sequencers enabled rapid experimentation, while digital recording (and later, compact discs) allowed for flawless edits and crisp sound. Suddenly, riddims could be composed, recorded, and distributed at lightning speed.

By the 2000s, software like Pro Tools, Cubase, and FL Studio became the new standard. Producers could now record, manipulate, and remix tracks with a click. Old-school roles blurred: one person armed with a laptop could handle everything from composing the riddim to mastering the final track. This democratization of music-making made dancehall accessible beyond Jamaica, sparking creative waves in places like the UK, Japan, and Africa.

Internet platforms—YouTube, SoundCloud, and WhatsApp groups—have also become unofficial studios. Riddims and a cappella vocals circulate within hours, enabling spontaneous collaborations across continents. The speed and flexibility of today’s digital landscape encourage the constant reinvention that defines dancehall’s sound.

Global Expansion and Hybrids: Crossroads of Culture and Technology

The technical language of dancehall has shaped more than its own genre. As the Jamaican diaspora spread, so did the tools and production tricks behind the music. Producers in London, New York, Lagos, and beyond borrow dancehall’s modular riddim structure, fast-paced beats, and bass-centric mixing for everything from grime to reggaeton.

In the process, dancehall technology itself continues to evolve. International producers tweak the riddims with new flavors—blending South Asian percussion in the UK, African polyrhythms in Nigeria, or Latin American dembow in Puerto Rico. The software and studio techniques pioneered in Kingston find new life as hybrid genres, all built on the technical groundwork laid decades before.

Through it all, the genre’s central technical principles—strong riddims, inventive vocal processing, and relentless sound system energy—form the anchor for creative innovation worldwide. Each new adaptation, remix, and reinvention adds another layer to dancehall’s ongoing story, demonstrating just how far technological vision and musical imagination can travel together.

Beyond the Beat: How Dancehall Shaped Identity and Challenged the World

Sound Systems and Street Life: The Heartbeat of Jamaican Communities

Dancehall’s cultural significance can’t be untangled from the everyday lives of Jamaicans in the late twentieth century. The sound system was not just a musical setup—it became a focal point for social gathering, collective joy, and, at times, tension-filled conversations. On bustling street corners and in open lots, speakers towering like city landmarks blasted riddims into the night air, forging a sense of togetherness. For countless young people in Kingston’s densely packed neighborhoods, these parties weren’t just entertainment; they were expressions of defiance and hope.

The DIY spirit of dancehall empowered local entrepreneurs. Young sound system operators invested in imported speakers, amps, and vinyl records, often pooling resources to build something greater. These makeshift dance parties became vital spaces where the latest tracks by stars like Yellowman or Josey Wales could premiere and local talent could rise. Dancehall, in this sense, was both stage and community noticeboard—a place to build reputations, test new slang, and spark dance trends.

This environment allowed dancehall to function as a kind of informal news outlet. When events shook the city—political unrest, poverty, or the highs and lows of daily survival—artists quickly turned them into lyrics and performances. Crowds listened, responded, and debated through call-and-response, making the music a forum for real-time dialogue.

Language, Slang, and Dancehall’s Role in Shaping Identity

One of dancehall’s most transformative impacts lies in its reinvention of language. Jamaican Patois, often dismissed in official circles, moved to center stage in dancehall lyrics. Performers like Papa San and Super Cat broke free from formal English, creating clever, rapid-fire lines packed with metaphor and humor. The genre made patois trendy, legitimate, and powerfully expressive.

Moreover, the slang generated in dancehall didn’t just stay in Jamaica. From the late 1980s onwards, words and catchphrases from popular tracks started filtering into international pop culture, especially in Britain, Canada, and the United States. Songs such as Murder She Wrote by Chaka Demus & Pliers left their mark far beyond the island, infusing mainstream club culture with Jamaican wit and flavor.

Dance, too, became an essential element of identity. Signature moves like the bogle and the butterfly emerged directly from Kingston’s dancehalls, quickly spreading across the Caribbean and diaspora communities. These dances became as symbolic as the music itself—short routines packed with swagger, playfulness, and community pride.

Politics, Social Commentary, and a Platform for the Voiceless

In the context of 1980s and 1990s Jamaica, where political violence and social tension were everyday realities, dancehall morphed into an uncensored diary of public feeling. Unlike earlier reggae, which often urged peace and unity, dancehall sometimes leaned into rawer topics—documenting struggles with poverty, policing, and ghetto realities. Artists such as Beenie Man and Bounty Killer turned tracks into hard-hitting street chronicles, using their verses to both reflect on hardship and demand change.

At times, these lyrics sparked controversy. Critics saw dancehall as too explicit or violent, but for many marginalized Jamaicans, it offered the rare ability to speak freely and be heard. Across the island, and in diaspora hubs like London and New York, these honest, sometimes confrontational stories gave voice to frustrations that society often ignored.

Furthermore, the genre blurred the line between entertainer and social activist. Performers like Lady Saw, one of dancehall’s earliest female stars, flipped the gender script with lyrics exploring romance, power, and survival from a woman’s point of view. This shook up not only the male-dominated music industry but also wider societal expectations about gender roles.

Global Expansion: Dancehall’s Influence on Fashion, Slang, and Mainstream Music

Dancehall’s electrifying energy wouldn’t stay confined to, or even defined by, Jamaican borders for long. By the 1990s, the genre’s infectious production style, along with its attitude, started echoing across the world. International collaborations multiplied—think of Shaggy’s chart-dominating Boombastic or Sean Paul’s dancefloor anthems like Get Busy. These artists, blending Jamaican roots with global sounds, took dancehall to every continent.

The influence extended far beyond music. Urban fashion absorbed the bold aesthetics of dancehall, from bright colors and tight-fitting clothes to elaborate hairstyles often first seen in Kingston’s dancehalls. In London, Toronto, and New York, young people adopted not only the music but also the style—the sharp hats, branded shirts, and gold chains.

Dancehall slang and themes even penetrated other musical genres. American hip-hop producers borrowed riddims, rhythms, and vocal styles, with songs like Jay-Z’s Big Pimpin’ and Rihanna’s Rude Boy carrying unmistakable dancehall DNA. African pop, especially in Nigeria and Ghana, found inspiration in Jamaica’s beats and vocal phrasing, giving rise to afro-dancehall hybrids.

Immigrant Stories, Diaspora Pride, and the Dancehall Diaspora

Among Jamaican immigrant communities, dancehall provided an anchor—a link to home that was deeply personal and collective at once. Family parties, church hall gatherings, and pirate radio shows in London’s Brixton or Brooklyn’s Flatbush created mini-Jamaicas abroad, with dancehall the preferred soundtrack. In these settings, music wasn’t simply recreation—it became a tool to build self-esteem, resist assimilation, and memorialize a homeland many dreamed of returning to.

In Toronto, for instance, DJs like Ron Nelson gave local youth a chance to hear the latest dancehall imports alongside homegrown talent. Temporary venues called “bashments” packed hundreds into community centers, while pirate stations broadcast late-night sets filled with the newest riddims. These moments of togetherness gave second-generation Jamaicans and wider Black communities new ways to explore their roots.

Furthermore, dancehall’s rise paralleled wider Black identity movements globally. Lyrics celebrating everyday hustle or denouncing injustice offered important narratives for other communities negotiating their own sense of belonging. Dancehall, in this way, became a shared language for the wider African diaspora.

Technology, Social Media, and New Generations

With the arrival of cheap recording equipment and, later, the internet, dancehall democratized even further. Young creators could now upload tracks from bedrooms in Kingston, London, or Lagos without needing a record label or studio budget. Platforms like YouTube and SoundCloud gave fresh faces a way to build audiences within days, sometimes breaking into international charts with one lucky upload.

Social media’s global reach has intensified dancehall’s feedback loop. Viral challenges—like the gully creeper or dutty wine—sparked international dance crazes overnight. Aspiring dancers in Tokyo or Paris could master moves originated by Kingston’s teenagers, then create their own variations and share video clips online.

This connectivity keeps dancehall fresh and unpredictable. As older stars pass the mic to the next wave—artists such as Popcaan and Spice—the genre remains a living, breathing force. New riddims, dances, and stories emerge, all while honoring the deep roots from which dancehall sprang.

In every beat, rhyme, and move, dancehall continues to challenge, empower, and connect—linking streets in Kingston with neighborhoods the world over, ensuring its story is always unfinished and always evolving.

Soundclash Nights and Streetlight Stages: Where Dancehall Comes Alive

Gathering Under the Stars: Dancehall’s Open-Air Ritual

As dusk settles over Kingston, the rhythm of everyday life shifts. Streetlights flicker on, and the familiar buzz of anticipation rises from every corner. For many in Jamaica—and far beyond—the true pulse of dancehall isn’t found in radio hits, but in its electricity-charged, open-air performances known locally as “sessions.” These events transform streets, empty lots, and community centers into spaces where music, dance, and rivalry collide.

At the heart of this tradition are powerful sound systems: towering stacks of speakers, mixing consoles, and turntables. Crews spend hours setting up their rigs, each determined to deliver the loudest, clearest, and most captivating experience. Local vendors set up stalls offering spicy jerk chicken, icy drinks, and booming laughter, creating a festival-like atmosphere. The audience gathers not just to listen, but to feel the music in their bones—a communal ritual woven deeply into everyday Jamaican culture.

Moreover, the energy between performers and crowd often drives the night’s direction. When a selector—the person choosing and spinning tracks—drops a fan favorite, the eruption is immediate: cheers, whistles, and the unmistakable sound of horns fill the air. In turn, performers, known as deejays, feed off this momentum. This dynamic conversation shapes the living culture of dancehall, where no two nights are ever quite the same.

The Art of the Soundclash: Rivalry and Respect

One uniquely Jamaican phenomenon defines dancehall’s live culture: the legendary soundclash. At its core, a soundclash is an intense musical showdown between rival sound system crews, each determined to outdo the other with sharper selections, special remixes (dubplates), and crowd-shaking exclusives. Unlike typical concerts, where artists play through a setlist, a soundclash is a battle of wit, creativity, and showmanship, with the audience serving as fierce, vocal judges.

Crews like Stone Love, Killamanjaro, and Bass Odyssey have risen to legendary status through countless clashes. These events might last until sunrise, with selectors firing off obscure tracks, custom versions with deejays’ personal greetings, and rapid-fire lyrical barrages from star MCs. The rivalry isn’t just technical—it’s deeply personal. Salvos of clever lyrics—often crafted on the spot—are aimed directly at competitors, fueling a back-and-forth exchange that raises the night’s tension.

However, there’s always an underlying current of mutual respect. Most clashes end with opponents acknowledging each other’s skill, creativity, and command over the crowd. For fans, soundclashes are more than entertainment; they are living displays of musical craftsmanship, quick-thinking improvisation, and community pride. It’s here that reputations are made—and sometimes broken—in real time, under the scrutiny of a passionate audience.

Performance as Proving Ground: Freestyle, Fashion, and Dance

Unlike many other music genres, dancehall’s performance culture is built on spontaneity. On any given night, a deejay might grab the microphone and launch into an unscripted freestyle—tailored to the rhythms thundering from the speakers and the mood swirling in the air. This ability to improvise is considered a mark of true talent, separating journeymen from future icons.

Emerging artists often cut their teeth in these live settings, vying for the audience’s approval with clever rhymes and fearless stage presence. One standout example is Super Cat, whose quick wit and playful braggadocio in the dance put him on the map during the 1980s. Crowds demanded versatility: an MC not only had to command the mic, but also captivate listeners with storytelling, humor, and raw energy.

Performance in dancehall extends far beyond music, blending closely with fashion and dance trends. Attendees treat each gathering as a runway of self-expression. Loud prints, eye-catching jewelry, and inventive haircuts are all part of the spectacle. For many, outshining the stars on stage through bold style is just as important as catching every lyric. Meanwhile, new dances—like the “Bogle” or the “Dutty Wine”—are often premiered at these events before exploding into national and global dance trends. The dancefloor becomes a laboratory for movement, with participants inventing and perfecting routines as the music booms.

From Kingston’s Yards to Global Arenas: The Spread of Dancehall Live

While dancehall’s live tradition was born on Jamaica’s streets, its energy could not be contained. Diasporic communities in London, Toronto, and New York soon hosted their own soundclashes and street dances, adapting the format but preserving its competitive and participatory spirit. Jamaican exiles established new crews—like Saxon Sound in England—bringing the raw excitement and improvisational flair of Kingston sessions to clubs and festivals abroad.

This global migration transformed the idea of a dancehall performance. Suddenly, audiences around the world were captivated by the sheer dynamism of the genre’s live experience. International stars, including Shabba Ranks and Beenie Man, began taking the dancehall ethos to massive festivals. Their concerts, though staged in giant arenas rather than neighborhood lots, retained core elements: call-and-response routines, high-octane toasting, and the visual spectacle of coordinated dance troupes moving in sync to the riddim.

The technical tools evolved as well. Modern tours often employ advanced sound reinforcement and lighting effects, yet the emphasis remains on crowd interaction and improvisation. Even today, whether in a sweltering Kingston yard or a packed Tokyo club, the unbreakable bond between performer and audience is the pulse that drives every dancehall event.

Technology, Media, and the Evolution of Experience

From the earliest days, dancehall relied on the latest technology to amplify its message. The significance of the sound system was not just its volume but its ability to transform performance itself—allowing artists to reach massive audiences and experiment with echo effects, sirens, and other live manipulations. As cassette tapes, then later video recordings, became more accessible in the 1980s and 1990s, the culture of “live tapes” emerged. These bootleg recordings from legendary nights circulated far beyond Jamaica, spreading new catchphrases, styles, and rivalries throughout the diaspora.

With the arrival of the internet and social media, dancehall’s live culture has experienced another seismic shift. Fans can now watch highlights from a Kingston soundclash on their smartphones from nearly anywhere. Platforms like YouTube and Instagram have made it possible for new dance moves, performance styles, and up-and-coming deejays to achieve global cult status overnight. Still, seasoned fans agree that nothing replicates the magic of being front and center when a heavy riddim drops and the entire crowd moves as one.

Future Frontiers: Reinvention and Resilience

As dancehall’s reach extends further, its performance traditions continually reinvent themselves. Younger generations experiment with new sounds and presentation styles while fiercely guarding the experimental, grassroots essence of live dancehall. Collaborations with pop, hip-hop, and Afrobeats artists have brought new audiences into the circle, blending global trends with local flair.

Yet no matter how the genre evolves or how technology advances, the foundation remains the same: dancehall comes alive in the gathering, the contest, the movement, and the moment when music and community merge under the glow of streetlights or festival spotlights. The future of dancehall’s performance culture lies in its ability to adapt without losing the raw energy and interactive spirit at its core—ensuring that every night, somewhere in the world, the dance continues.

From Yard to World Stage: Dancehall’s Dynamic Journey

Breaking Binaries: The Digital Revolution Sparks New Rhythms

The early 1980s marked a moment that would permanently reroute dancehall’s evolutionary path. While reggae had dominated the ’70s, the dawn of a new decade brought rapid change, led most strikingly by Kingston’s youthful producers and hungry artists. Before this turning point, dancehall’s sound relied heavily on analog recording and live bands, with studios echoing to the slides and slaps of real drum kits and bass guitars. This approach gave classic productions by figures like King Tubby and Sly & Robbie their distinct warmth—something close and human in each groove.

However, the arrival of affordable digital synthesizers and drum machines sent a shockwave through every corner of Jamaica’s music scene. When King Jammy and his team unveiled Under Mi Sleng Teng in 1985—a track built almost entirely on the preset rock rhythm of a cheap Casio MT-40 keyboard—the atmosphere changed overnight. It wasn’t just a catchy tune; the Sleng Teng riddim signaled a fresh aesthetic, one that broke free from the organic reggae pulse and embraced punchy, computerized beats. Suddenly, anyone with a keyboard and a cassette deck could become a producer. This democratization upset established hierarchies, giving rise to homemade studios and countless contenders ready to claim their spot in dancehall’s ever-evolving hierarchy.

Moreover, the digital shift fueled experimentation with form and texture. Producers chopped and looped samples, programmed faster rhythms, and layered crisp snares with thick, synthesized bass lines. These new riddims lent dancehall a sense of urgency and precision that echoed Jamaica’s restless youth culture. The impact rippled outward, with artists like Wayne Smith and Tenor Saw swiftly adapting their vocal styles to fit the new, less forgiving, digital backdrops—a move that would define the music for decades to follow.

Lyrical Battlegrounds: The Rise of Deejays and Vocal Innovation

As dancehall’s heartbeat became more mechanical, its vocal tradition also underwent a profound transformation. In the 1970s, the main vocal approach was the crooning, soulful style heard in lovers rock or roots reggae. Yet, as riddims grew starker and digitalized, the spotlight shifted toward “deejays”—a Jamaican term for artists who chant or rap in rhythm, not to be confused with the DJs who spin records in Western dance clubs.

Trailblazers like Yellowman, Eek-A-Mouse, and Sister Nancy took center stage, forging a new lyrical identity for dancehall. They traded extended melodies for sharp, rhythmic “toasts”—a mixture of wordplay, social commentary, and playful boasting. This style, which often included quick-witted responses and rapid-fire delivery, brought the tradition of “sound system clashes” onto studio recordings. The energy of live battles bled into the music itself.

This period was also fiercely competitive. Deejays wrote lyrics that addressed local news, social inequalities, and personal rivalries, feeding off audience reactions at sound system battles and dancehall events. Themes ranged from gritty street survival to sexual innuendo and political protest. The sheer speed at which deejays responded to events gave the genre a raw immediacy—the music could voice community anxieties almost in real-time.

Female deejays such as Lady Saw and Sister Charmaine soon claimed their space, challenging gender norms within a male-dominated sphere. Their bold, confrontational lyrics redefined what was possible for women in Jamaican popular music, laying groundwork for future generations of artists to explore gender and sexuality through the dancehall lens.

Street to Satellite: Urban Roots, Global Echoes

By the 1990s, dancehall’s pulse no longer beat exclusively in Kingston’s streets. The rise of cable television, international radio programs, and major music video channels exposed the genre to audiences far beyond Jamaica’s shores. Diaspora communities in London, New York, and Toronto played a pivotal role in spreading the sound, holding street parties and pirate radio sessions that echoed the spirit of Jamaican dancehall but adapted it for new urban contexts.

This global exchange worked both ways. International pop artists began seeking out Jamaican producers and incorporating dancehall’s syncopation and celebration of “riddim culture” into their hits. Collaborations such as Shabba Ranks with American rappers, and later, crossover successes like Sean Paul’s Get Busy or Shaggy’s It Wasn’t Me, propelled dancehall into the pop mainstream. The music’s infectious energy, built on the universal language of rhythm and storytelling, proved irresistible on dance floors from Lagos to Tokyo.

Meanwhile, as dancehall’s popularity soared, Jamaican artists began experimenting with elements from hip hop, R&B, and even African afropop. The blend was not one-way. American hip hop producers, for instance, drew heavy inspiration from dancehall’s sound system culture and riddim-driven songwriting, looping reggae samples and even hiring Jamaican deejays for guest spots. This cross-pollination broadened dancehall’s influence, cementing its status as a global musical force.

Controversy and Reinvention: Navigating Changing Times

Despite its growing acceptance in international circles, dancehall has often sparked controversy—both at home and abroad. Lyrics addressing violence, sexual freedom, and political protest frequently drew criticism from politicians, censors, and advocacy groups. Disputes about “slackness”—a term for lyrics perceived as sexually explicit—raged through the late 1980s and 1990s. Debates over taste, morality, and censorship forced artists and fans to question music’s role as both social mirror and cultural influencer.

In response, many artists reinvented themselves or shifted their message, introducing “conscious dancehall” with an emphasis on social uplift, anti-violence themes, and African pride. Performers like Buju Banton and Capleton rose to prominence by blending energetic, crowd-pleasing riddims with pointed views on Jamaican society. Some adopted Rastafarian imagery, while others explored themes of religious awakening or self-improvement.

Changes in Jamaica’s technology and society also pushed dancehall’s sound into new territories. Cheap home studios, computer-based recording, and global social media all made it possible for young artists to produce, share, and distribute tracks independently. This digital empowerment lowered entry barriers—anyone with a laptop and imagination could generate riddims, upload videos, and grow a fan base from scratch.

Looking Forward: Dancehall’s Ever-Adapting Spirit

As the twenty-first century advances, dancehall’s development continues at a breakneck pace. New generations of producers and performers build on decades of innovation, fusing the DIY ethos of early sound systems with new technology and global sensibilities. Viral “dance challenges,” trap-influenced riddims, and collaborations with K-pop or EDM stars show that dancehall’s original spirit of experimentation is alive and thriving.

What remains constant is the genre’s adaptability and rootedness in both local and global communities. Dancehall still gives voice to everyday realities in Jamaica, while simultaneously inspiring listeners worldwide to find their own meanings within its rhythms and lyrics. Every club night, festival stage, and mobile phone playlist ensures the genre’s story will keep evolving, echoing far beyond its island homeland.

Riddims Without Borders: Dancehall’s Enduring Impact Across Continents

Shaping Global Sounds: Dancehall’s Fingerprints in Modern Music

Few genres have managed to leave such a recognizable signature on international music as dancehall. The influence of this Jamaican powerhouse echoes far beyond the island’s shores, infusing mainstream sounds worldwide with its energy, vocabulary, and swagger.

In the 1980s and 1990s, as digital technology made music easier and cheaper to produce, dancehall’s sharp, catchy rhythms—known as riddims—began filtering into global pop culture. Producers in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Africa rapidly picked up dancehall techniques, experimenting with digital beats, rapid-fire lyrical flows, and bold sonic textures. From New York to London, songs with a dancehall flavor started topping charts and filling dance floors.

A prime illustration is the rise of Shaggy, who moved from Kingston to Brooklyn and brought the yard’s unmistakable style to a worldwide stage. His hits like Boombastic and It Wasn’t Me gave global audiences an accessible entry point into dancehall’s world. Meanwhile, UK-based artists such as General Levy and Smiley Culture merged dancehall’s rhythmic intensity with British sensibilities, resulting in innovative “jungle” and “ragga” tracks that still inform today’s electronic music.

Crucially, dancehall not only blends with mainstream genres—it often shapes their direction. The syncopated beats and captivating basslines of dancehall can be heard pulsing through reggaeton, grime, afrobeats, hip hop, and even American pop. Collaborations between Jamaican icons and international stars—like Sean Paul’s work with Beyoncé on Baby Boy—demonstrate how dancehall’s DNA has fundamentally changed the soundscape of popular music.

Reinventing Identity: Language, Fashion, and Cultural Dialogues

Beyond the songs themselves, dancehall transformed how people talk, dress, and move around the world. Its inventive vocabulary and distinctive slang have colored global youth culture, even among listeners who have never set foot in Kingston. Phrases like “irie,” “bashment,” and “gyallis” migrated from local patios in Jamaica to social media, Instagram captions, and song lyrics everywhere.

The genre’s bold fashion sense—think bright colors, oversized jewelry, and creative haircuts—became a visual code for rebelliousness and confidence. International stars from Rihanna to Drake have borrowed dancehall’s aesthetic in music videos, red carpet appearances, and fashion lines. These influences reach beyond music fans. Streetwear, sneaker design, and urban fashion owe much to the trends born on Kingston’s dance floors and sound system nights.

Moreover, dancehall has started global conversations about gender, sexuality, and self-presentation. Female artists such as Lady Saw and Spice challenged conservative norms, using dancehall’s platform to assert sexual agency and confront double standards. This freedom to self-define—sometimes provocative, always unapologetic—has inspired similar movements in urban and underground scenes from Lagos to London.

The Power of the Sound System: Spreading Dancehall’s Message

At the beating heart of dancehall’s reach is the mighty sound system. In Jamaica, these mobile music machines quickly became legendary, but their role didn’t end on the island. Enterprising migrants took the sound system culture abroad in the 1980s and 1990s, planting the seeds for vibrant new scenes in London, Toronto, Berlin, and Tokyo.

Wherever a sound system found a home, it attracted local artists, producers, and fans. Community events and basement parties provided spaces for cultural exchange, allowing new musical hybrids to emerge. For example, in the UK, the fusion of dancehall with local hip hop and electronic music birthed “jungle” and “UK garage”—distinctly British genres that owe their power to Jamaican innovation.

In many cities, sound systems did more than entertain. They offered marginalized communities a way to celebrate heritage and voice social concerns. The tradition of lyrical competition and spontaneous freestyle, central to dancehall, gave rise to battles, clashes, and open-mic nights that form the backbone of today’s hip hop and club cultures worldwide.

Digital Roots and DIY Dreams: Democratizing Music Production

The arrival of inexpensive technology in the 1980s played a critical role in expanding dancehall’s reach. Suddenly, aspiring producers were no longer limited by expensive studio sessions or complicated logistics. With a laptop or a simple drum machine, anyone could create, remix, and distribute new tracks. This democratized approach didn’t just keep dancehall alive in Jamaica—it allowed young people everywhere to shape the sound to their own experience.

In Toronto, Paris, Lagos, and Tokyo, independent artists carved out fresh takes on the genre, collaborating online and trading beats in real time. YouTube, SoundCloud, and other platforms became digital sound systems, boosting homegrown stars and spreading riddims globally within hours of release. The spirit of experimentation that drove dancehall’s earliest innovators continues to energize producers across generations.

Furthermore, this DIY movement inspired other genres to embrace home recording and grassroots promotion. Hip hop, grime, and various electronic subcultures all owe a debt to dancehall’s willingness to exploit new tools and break down boundaries between performer and listener.

Social Consciousness and Dancehall’s Double Edge

While dancehall is often celebrated for its party anthems and danceable grooves, its lyrics have also sparked intense debate. The genre’s ability to comment on social, economic, and political realities has made it both beloved and controversial. In the 1980s and 1990s, artists such as Shabba Ranks and Buju Banton captured the joys, struggles, and frustrations of life in Kingston’s rough neighborhoods, providing an uncensored window into a world rarely acknowledged by mainstream media.

However, some dancehall tracks have attracted criticism for promoting violence or intolerance, especially towards women and LGBTQ+ individuals. These controversies have challenged artists and fans alike to confront the complexities of creative expression, social responsibility, and community values. In recent years, prominent voices within and beyond Jamaica have called for more conscious and inclusive lyrics, leading to significant debates about the genre’s future.

Through it all, dancehall’s role as a truth-telling platform endures. It offers a stage for marginalized voices, a mirror for society’s challenges, and—even in its fiercest moments—a catalyst for change and resilience.

New Generations, New Directions: Dancehall’s Ongoing Evolution

Today, dancehall continues to evolve at breakneck speed. Younger artists in Jamaica and the diaspora are expanding the genre’s boundaries, blending it with EDM, trap, afrobeats, and reggaeton. Innovators like Popcaan, Vybz Kartel, and Koffee are exploring new lyrical themes, sonic experiments, and collaborations. They demonstrate that dancehall’s legacy is not frozen in time, but alive and thriving in each new beat.

Moreover, global festivals, viral dance challenges, and international awards have brought dancehall to audiences who may never see a Kingston street session but still feel the music’s pulse. Growing recognition from the music industry, including major streaming platforms and award shows, points to a future where dancehall’s inventiveness and rebellious spirit inspire artists and listeners everywhere.

Whether on a rooftop in London or a beach party in Accra, dancehall’s riddims and stories remind the world that music can defy borders, ignite revolutions, and spark joy in the most unexpected places.