Glitches and Neon Dreams: Vaporwave’s Digital Fantasies

Born online in the early 2010s, vaporwave blends vintage synths, chopped samples, and faded internet imagery. Celebrated acts like MACINTOSH PLUS and Saint Pepsi capture nostalgia for retro technology and lost consumer dreams.

Echoes of the Mall: Vaporwave’s Origins in Digital Nostalgia

From 1980s Consumer Culture to the Neon Glow of the Internet

Vaporwave’s roots stretch back further than its digital arrival in the early 2010s. To understand where it comes from, it’s essential to look at the “mall culture” and shiny consumer dreams of the 1980s and 1990s. Throughout these decades, shopping malls, pastel commercials, and new home technologies created an atmosphere of playful optimism in North America and beyond. The soundtracks to malls and adverts were built on smooth jazz, soft rock, and elevator music—sometimes called “muzak”—intended for easy listening as background to everyday shopping and leisure.

These environments helped define the atmosphere that vaporwave artists would later sample, deconstruct, and exaggerate. Children of the ’80s and ’90s grew up surrounded by corporate jingles, shiny electronics, and promises of a high-tech future, only to find these dreams fading as the decades changed. As the internet matured and technologies from these eras fell out of favor, a lingering, bittersweet nostalgia for this lost optimism emerged online. This nostalgia became the emotional wellspring that vaporwave would channel and transform.

With the rapid spread of the internet in the 2000s, music production itself saw a radical transformation. Affordable software and easy file distribution let home producers experiment with sampling, editing, and remixing on a scale never seen before. Social networks, forums, and especially platforms like Bandcamp gave digital artists new avenues to share and spread their music directly to listeners around the world. These conditions set the stage for the birth of vaporwave as a cohesive style—one that didn’t just look back at the past, but manipulated it for new artistic meaning.

Sampled Memories: The First Vaporwave Alchemy

The first artists to shape vaporwave’s identity operated almost entirely in the digital underground. Around 2010 and 2011, innovative producers began sharing music that played with sluggish tempos, dreamy synth textures, and easily recognizable samples of 1980s and 1990s corporate music. Daniel Lopatin, already known under the name Oneohtrix Point Never, sparked interest with his 2009 project Eccojams Vol. 1, released as Chuck Person. He slowed down and repeated tiny fragments of old pop and soft rock, looping simple lines until they felt haunting and distant. This new approach captured the feeling of “remembering” the past through scratched videotapes and corrupted MP3 files, rather than hearing it in crystal clarity.

Simultaneously, other producers were surfacing online with similar ideas. In 2011, the album Floral Shoppe by MACINTOSH PLUS (an alias of Vektroid, real name Ramona Xavier) became a viral sensation. Tracks like Lisa Frank 420 / Modern Computing built lush, surreal soundscapes out of chopped-up Japanese pop songs and TV ad fragments. The results felt familiar yet alien—equal parts comforting and uncanny.

The use of sampling in vaporwave was itself quite distinct. While hip-hop and dance producers often sampled older music to create propulsive new songs, vaporwave artists lingered on simple melodic loops, slowing them down until they felt dreamlike or even mournful. Effects like reverb and deliberate audio errors gave the music the character of old VHS tapes or fading memories. This wasn’t just a technical choice—it was a commentary on the disposable nature of consumer goods, the rapid turnover of trends, and a skepticism toward the ideals sold through mass media.

Art, Irony, and the Internet: Vaporwave’s Conceptual Foundations

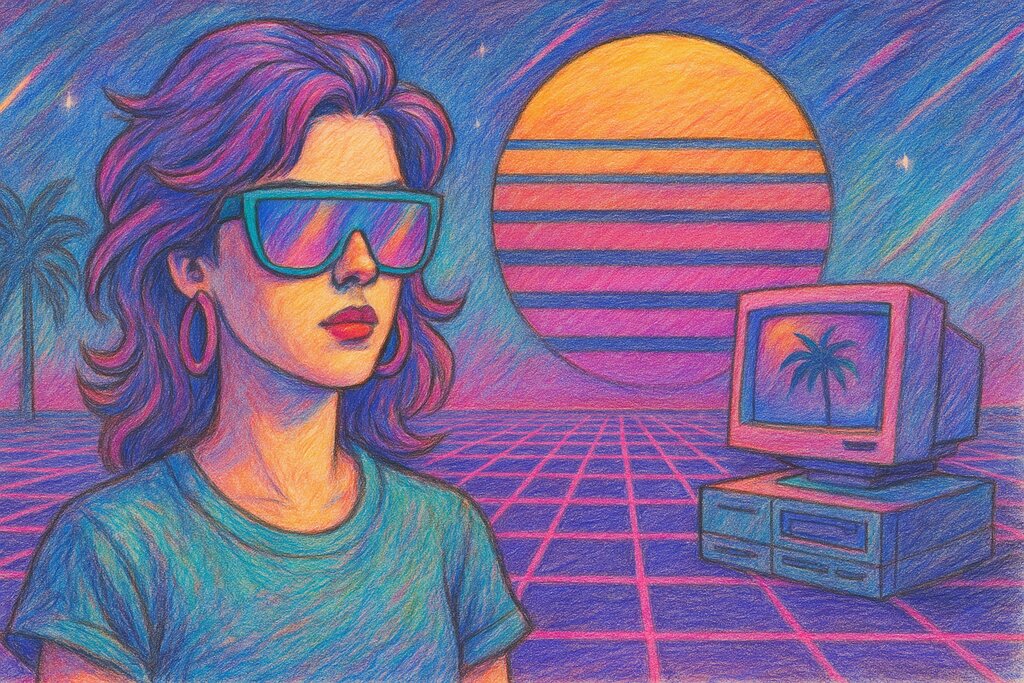

From its earliest moments, vaporwave did more than play with sound. It turned internet culture, visual aesthetics, and irony into essential parts of its identity. The genre’s musicians and graphic designers drew on the styling of early PC interfaces, neon lights, and the blocky graphics of 1990s digital art. Album covers featured Roman busts, Japanese text, chrome logos, and cityscapes—symbols that mixed past and future, East and West, and real commerce with virtual reality.

Irony was a central theme. While some listeners approached vaporwave as a sincere tribute to lost decades, others enjoyed it as a tongue-in-cheek critique of capitalism. Many creators—like James Ferraro with his acclaimed 2011 album Far Side Virtual—used glossy, hyper-commercial sounds to satirize the utopian promises of consumer tech. Tracks borrowed the cheerful digital tones of ringtones, startup jingles, and menu screens, exaggerating them into something both celebratory and unsettling.

The online communities that formed around vaporwave’s earliest releases played a critical role in shaping the genre’s direction. Sites like Tumblr and Reddit helped these sounds and images go viral. Visual artists collaborated with musicians, reinforcing the obsessive recycling and remixing of familiar sources. Memes, remixes, and fan edits blurred the line between creators and audience, making vaporwave as much a social phenomenon as a traditional musical genre.

Microgenres, Global Spread, and Cultural Reverberations

As vaporwave’s popularity grew, it quickly fractured into sub-genres—each emphasizing different elements of its sonic and visual language. Saint Pepsi (later known as Skylar Spence) emerged in 2013, blending funk and disco samples into energetic, danceable versions of vaporwave, often referred to as “future funk.” Meanwhile, subgenres like “mallsoft” focused on recreating the echoing ambiance of deserted shopping malls, while “signalwave” chopped radio and TV signals into repetitive sound collages. This diversity allowed people from all backgrounds to find a style that resonated with their own memories and tastes.

Internationally, vaporwave became a surprising bridge between cultures. Japanese city pop—a sleek, urban style of 1980s pop music—became one of the genre’s most sampled sources, introducing Western listeners to artists like Mariya Takeuchi and Tatsuro Yamashita long before their resurgence on streaming platforms. In Japan, vaporwave’s imagery of “Aesthetic” (a term referencing its pastel, artificial style) found an audience eager to explore global digital nostalgia.

Outside North America and Asia, the genre also caught on with independent producers in Europe, Latin America, and beyond. Sonic footnotes of old commercials, forgotten European radio hits, and even home video sounds filtered into new releases. The universal experience of growing up surrounded by televisions, shopping centers, and disposable technology meant that vaporwave’s message resonated almost everywhere.

The Role of Technology and Cultural Shifts

Vaporwave’s success cannot be separated from the cultural and technological shifts of the early 21st century. The collapse of many brick-and-mortar stores, fading relevance of physical media, and rapid pace of digital innovation created a hunger to process the recent past. Music software allowed unprecedented control over audio manipulation—a user could warp a sample in minutes and share it with the world all in one evening.

Moreover, economic uncertainty after global recessions in the late 2000s made the easy consumer narratives of the 1980s and 90s feel especially distant. For Gen Z and Millennials, vaporwave offered both a way to mourn what was lost and to satirize the promise that endless progress could be bought at a shopping mall. Scenes from old sitcoms, snippets of forgotten infomercials, and the bright electronic soundtracks of extinct operating systems all became building blocks for a new, digitally native form of nostalgia.

Today, vaporwave’s sensibility continues to inform digital art, fashion, and even mainstream pop music. Its origin story stands as a case study in how online communities, cheap technology, and a questioning attitude toward consumer excess can create an entirely new genre—one built on the memories of a world both real and simulated. As long as there are new digital landscapes to explore and old electronic ghosts to haunt them, vaporwave’s story will keep evolving.

Shattered Sounds and Glitched Memories: Inside Vaporwave’s Sonic Universe

Sampling the Past, Warping the Present

Central to the vaporwave experience is the art of sampling—taking pieces of existing music and repurposing them for a new era. Unlike traditional remixing, which often aims to update a hit, vaporwave samples with a twist: the goal is to amplify the uncanny and nostalgia-soaked atmosphere of long-lost decades. Instead of focusing on the latest chart-toppers, artists pluck fragments from dated muzak, smooth jazz, and early digital pop typical in shopping malls, ’80s infomercials, or forgotten video games.

MACINTOSH PLUS made waves with Floral Shoppe, an album built almost entirely from re-pitched, slowed-down bits of 1980s adult contemporary tracks. These manipulated samples are sometimes stretched until melodies become unrecognizably hazy, and vocals, if they appear, are twisted or looped for surreal effect. The result is music both familiar and strange—like tuning into a distant radio station from a parallel world.

This sampling technique is more than simple nostalgia, though. Vaporwave often pushes the original source so far that it reveals the empty, almost haunting quality of corporate soundtracks, exposing the artificial optimism of a former age. By looping cheesy saxophone riffs, glossy electric piano flourishes, or airbrushed vocal snippets, the music turns its source material into an experience designed to make listeners pause and reflect on the passage of time.

What makes vaporwave unique is how these samples are re-contextualized using modern production techniques. Cut-up sound fragments “glitch out” with abrupt stops, cascading echoes, or heavy reverb. These effects deepen the immersive feeling, casting an eerie digital shadow across every track.

Slow Motion Grooves and Hypnotic Loops

Slowing down audio is a signature trick in vaporwave production. Artists deliberately stretch tracks so the tempo crawls, bass booms become more pronounced, and high frequencies fade into a luxurious haze. This gives the music a sense of weightlessness—a kind of dreamlike drag that sets vaporwave apart from faster, more energetic genres like synthwave or house.

The slowed tempos invite listeners to linger in each moment, savoring every synthetic chord and echoing drumbeat. Rhythms often loop endlessly, transforming simple motifs into hypnotic patterns. Instead of big pop hooks or explosive drops, vaporwave leans into subtle repetition and gradual evolution.

Saint Pepsi built entire tracks—like Enjoy Yourself—by looping short musical phrases and gently layering effects until the line between source material and new creation blurs. Each repetition becomes a meditation on memory, evoking the feeling of being lost in thought as past and present intermingle.

Looping, too, has a double purpose: it gently mocks the forever-on nature of consumer culture’s background music and simultaneously offers a strange sort of comfort. The endless sonic cycles can sound soothing or unsettling, depending on the ears of the listener.

Digital Decay: Effects and Texture as Storytellers

Vaporwave’s lasting appeal lies in its unique sense of texture. Listeners are plunged into a world where audio intentionally decays, bristles with static, and fades like an aging VHS tape. Whereas most mainstream genres aim for sparkling clarity, vaporwave piles on digital artifacts—glitches, pitch bends, audio dropouts, and saturated distortion.

This “decay” is not an accident but a calculated aesthetic, designed to mimic the experience of living with aging technologies. For an entire generation who grew up rewinding cassettes, blowing dust from cartridges, or watching fuzzy late-night cable TV, these sonic imperfections evoke vivid sensory memories.

On albums like 新しい日の誕生 by 2814, layers of synthetic ambiance and swelling noise create an immersive soundscape that feels simultaneously lush and corroded. Reverb is often applied with a heavy hand, sending sounds tumbling into vast, empty digital spaces. Processing vocals until they sound ghostly and distant adds to the barely remembered quality of many tracks.

Such audio textures do more than just generate an “old school” sensation—they embody a subtle critique of both past and present, suggesting that the drive for endless technological progress always leaves something behind in the static.

Visuals as Vital Sonic Components

Vaporwave blurs the line between eyes and ears by giving as much attention to visuals as to sound. Glitches, pastel colors, 3D computer graphics, Japanese text, and distorted logos are not just window dressing—they are tightly bound to the sonic identity of the genre. Album covers and music videos become extensions of the music’s swirling unreality.

Some artists, like ESPRIT 空想 (an alias of Saint Pepsi), use their cover art and aesthetic choices to signal a deliberate distance from modern digital polish, instead embracing the “low-res” world of 1990s web graphics and magazine ads. This creates an interactive playground where hearing and seeing reinforce the vaporwave mood.

The visual dimension extends into live performances and online communities as well. Virtual vaporwave events often feature looping digital animations and interactive environments, immersing fans in a world of artificial nostalgia.

Technology as Creative Catalyst

It’s impossible to separate vaporwave from the digital tools that brought it to life. Cheap or free editing software, audio manipulation plugins, and home computers made it possible for anyone to create convincing vaporwave—even on a shoestring budget. The genre’s foundations in internet forums and file-sharing sites gave rise to its “do-it-yourself” ethos.

Bedroom producers from around the globe constructed entire albums using nothing but hand-me-down loops, cracked virtual instruments, and shared sample packs. This democratization of music-making helped vaporwave flourish as a truly international style, with scenes not only in North America and Japan but also in Europe, South America, and Australia.

Digital distribution through platforms like Bandcamp and SoundCloud allowed vaporwave projects to find audiences instantly, spawning countless microgenres. These substyles—ranging from the “mallsoft” of 猫 シ Corp., which centers on mall atmospheres, to the hyper-fantasy of “future funk”—demonstrate how quickly vaporwave artists adapt and remix their own formula.

Irony and Commentary in Every Chord

Part of vaporwave’s complexity comes from its playful sense of irony. By surrounding listeners with exaggerated commercialism, elevator music, and synthetic sentimentality, vaporwave both honors and gently mocks its influences. The result is an ongoing conversation about what it means to remember, reinterpret, and ultimately repurpose the dreams of past generations.

Governments, companies, and media once promised a frictionless future of endless convenience—promises that today feel distant. Vaporwave captures this sweet-sad realization, channeling both longing for yesterday and skepticism about the glittering images that shaped collective memory.

The genre’s approach resonates beyond music production. Vaporwave’s global popularity reflects growing curiosity about how technology, commerce, and pop culture shape personal and collective identities. Listeners from Tokyo to Berlin recognize traces of their own childhoods and digital lives woven into the shimmering fabric of vaporwave tracks.

In vaporwave’s musical universe, digital distortion, ancient samples, and bold visuals invite audiences to question the stories they’re told—and the stories they tell themselves. With every faded beat and looping motif, vaporwave encourages a second listen, revealing new layers of meaning each time.

Beyond Floral Shoppe: Vaporwave’s Ever-Expanding Universe

The Birth of Future Funk: Grooves from a Parallel Dance Floor

Among the earliest and most influential offshoots of vaporwave, Future Funk stands out with its infectious energy and glittering optimism. While classic vaporwave leans into somber moods and slow-motion nostalgia, future funk injects new life into retro sounds. Artists like Saint Pepsi and Yung Bae take samples from Japanese city pop—a genre of upbeat pop and funk from 1980s Japan—and reimagine them for digital-age dance floors.

The formula centers on chopping, looping, and layering these cheerful samples over tight electronic beats and punchy basslines. The result feels both retro and utterly contemporary—a daydream of roller-skating through neon-lit cityscapes. In contrast to vaporwave’s dreamy haze, future funk radiates with catchy hooks and celebratory rhythms, inviting listeners to dance rather than drift.

Equally important is the scene’s visual language. Future Funk artwork bursts with vibrant anime-style characters, pastel colors, and playful references to Japanese culture. This aesthetic, closely tied to the global appeal of anime and the vaporwave community’s fascination with East Asia, reveals how vaporwave subgenres adapt to new cultural influences while maintaining their vintage spirit.

Mallsoft: Wandering the Fluorescent Halls of Lost Utopias

Step into Mallsoft, and you’ll find yourself immersed in the ghostly ambiance of abandoned shopping centers. This subgenre embraces the architecture and sound design of malls themselves, carefully reconstructing the echoes, Muzak, and spatial audio that once filled these consumer temples. Where original vaporwave albums like MACINTOSH PLUS’s Floral Shoppe mangle and slow samples to create surreal atmospheres, mallsoft takes things even further.

Here, artists such as Cat System Corp. and Disconscious craft sprawling sonic installations, using reverb-heavy synths, public address announcements, and the soft shuffle of footsteps. The music conjures the feeling of wandering alone through empty halls, past food courts and mirrored escalators, long after the crowds have faded away.

Mallsoft doesn’t just recreate a bygone era—it explores the emotional aftermath of consumer excess and the cultural significance of retail spaces. For listeners who recall the golden age of malls or those who know it only through vintage photos, mallsoft becomes a vessel for both nostalgia and quiet critique. It invites listeners to daydream through the ruins of capitalism, reimagining shopping centers not as bustling venues but as haunted museums of memory.

Vaportrap: Hip-Hop’s Dreamy Twin in a Digital Landscape

As vaporwave’s community matured, some producers began to experiment by merging its lush atmospherics with the hard-hitting beats of modern hip-hop. This blend became known as Vaportrap—a subgenre that drapes classic trap rhythms in the shimmering textures and surreal samples characteristic of vaporwave.

Producers like Blank Banshee pioneered this style, releasing albums such as Blank Banshee 0 that meld skittering hi-hats, booming bass, and 808 drums with eerie chopped vocals and new-age synths. The effect is cinematic: a soundscape at once futuristic and nostalgic, as if hip-hop is being transmitted from a long-lost computer civilization.

The rise of vaportrap illustrates how vaporwave’s core techniques—like heavy sample manipulation and digital abstraction—can evolve through cross-genre pollination. The result attracts fans from both electronic and hip-hop communities, reflecting the increasingly porous boundaries between today’s musical styles.

Broken Transmission: Scrambled Signals from the Corporate Past

Digging deeper into vaporwave’s more experimental corners, Broken Transmission—also known as Signalwave—emerges as a collage that captures fleeting moments from a corporate media wasteland. Artists working in this style harvest tiny fragments from old TV news broadcasts, radio jingles, weather reports, and educational tapes. These bits are looped, glitched, and layered until meaning dissolves into static.

For instance, telepath テレパシー能力者 and Infinity Frequencies weave together samples of forgotten commercials and interstitials, pushing nostalgia past comfort and into something almost unsettling. Unlike the smooth, melodic approach of future funk, or the overt spaciousness of mallsoft, broken transmission feels frayed—as if the music itself is sifting through digital ruins in search of a lost signal.

This approach challenges listeners to confront the relentless churn of media and the fleeting nature of memory. In drawing attention to the ephemeral and disposable, the genre reflects a world spinning faster and more fragmented every day. For some, it’s a playful exercise in media archaeology; for others, it’s a quietly unnerving portrait of information overload.

International Echoes: Vaporwave Around the World

Although vaporwave began as a largely North American phenomenon, its influence has reached far beyond its origins. Producers from Japan, Brazil, Russia, and beyond have injected their own flavors and references, creating lively regional scenes and global variations.

In Japan, for instance, artists such as t e l e p a t h テレパシー能力者 and 84p reinterpret vaporwave’s aesthetics through the lens of technological optimism and local pop culture. Drawing inspiration from Tokyo’s urban landscapes, their music often samples Japanese commercials and jingles, giving new weight to the original mall-centric nostalgia. This localized approach adds nuance, reflecting how memories of consumer utopia vary from place to place.

Meanwhile, Brazilian collectives have championed distinctly Latin-tinged vaporwave. Producers like VaporwaveBR remix bossa nova and samba alongside international synthpop, tapping into unique local histories of modernity and commercialism. Instead of simply copying North American nostalgia, these adaptions allow vaporwave to explore themes of memory, loss, and hope in new global contexts.

The genre’s open-source attitude—where anyone with a computer can participate—both expands and diversifies the field. As vaporwave continues to cross borders and languages, its subgenres offer new ways to wrestle with digital memories, cultural futures, and shared pasts.

The Legacy of Remix: Why Vaporwave Keeps Morphing

At its heart, vaporwave’s countless subgenres expose an ongoing hunger for reinvention. Every new variation, from the club-ready polish of future funk to the chilling air of mallsoft, reflects not just nostalgia but a desire to interrogate our changing relationship with technology, commerce, and media.

This restless creativity is fueled by the internet’s culture of remix and reuse. Young producers sample, twist, and recontextualize not only music but movies, TV, and digital artwork, constructing micro-genres and niche communities almost overnight. As new generations access a trove of forgotten sounds, they add their own perspectives—transforming what began as a reaction to the collapse of one era’s consumer dreams into a worldwide mosaic of styles and stories.

In this ever-evolving landscape, vaporwave’s variations aren’t mere side-notes—they’re the core of its vitality. Each twist opens new spaces for expression, critique, and connection, hinting at endless possibilities for the digital artforms of tomorrow.

Icons of the Glitch: The Visionaries and Albums That Shaped Vaporwave

Breaking the Internet’s Mirror: MACINTOSH PLUS and the Enigma of Floral Shoppe

No discussion about vaporwave can begin without the mysterious figure behind the alias MACINTOSH PLUS. This project, crafted by American producer Vektroid (Ramona Xavier), shattered boundaries with Floral Shoppe in 2011. Released under the pseudonym MACINTOSH PLUS, the album became a foundational text—part sound experiment, part cultural manifesto.

What makes Floral Shoppe so unforgettable is its bold manipulation of already-familiar sounds. Xavier didn’t simply remix easy-listening and pop tracks from the 1980s; instead, she pulverized their tempo, stretched vocals into surreal textures, and looped fragments into hypnotic patterns. The iconic track リサフランク420 / 現代のコンピュー, known among fans as Lisa Frank 420 / Modern Computing, exemplifies this style. The sample, originally Diana Ross’s It’s Your Move, is slowed and chopped until it sounds like a dream playing on a dying mall speaker.

This album didn’t just influence other musicians—it introduced vaporwave to mainstream internet culture, thanks to its psychedelic pink cover and enduring meme status. Floral Shoppe turned the mundane into something strange and poignant. It’s been endlessly analyzed, remixed, and referenced, even a decade after its release.

Moreover, Xavier’s deft use of sampling was a blueprint for creators who came after. She drew attention to the way technology can both preserve and distort memory. The playful glitches and fuzzy nostalgia on Floral Shoppe reflect not only the moods of its listeners but also the shaky trust we place in our own recollections.

The Pantheon Expands: Vektroid’s Many Faces and Digital Storytelling

Beyond MACINTOSH PLUS, Vektroid has operated several influential aliases, each contributing a different hue to vaporwave’s sonic palette. The album Laserdisc Visions – New Dreams Ltd. (2010) mapped out a retro-futuristic universe built on shimmering synths and snippets of ’80s Japanese city landscapes. As PrismCorp Virtual Enterprises, Xavier turned toward artificial MIDI soundscapes in Home™ (2013) and ClearSkies™ (2013), gently parodying corporate background music and digital waiting-room tunes.

Through these projects, Vektroid demonstrated that vaporwave could be more than a genre tied to nostalgia. Her work playfully critiques the glossy surfaces of consumer capitalism and digital culture. These musical collages serve as a reminder: beneath the smooth polish of old commercials and muzak lies a strange, often unsettling emptiness.

Her approach blurs creative boundaries. Many vaporwave artists followed suit, inventing multiple alter egos and visual trademarks—mirroring the anonymity and fragmentation found online. This tendency shaped the genre’s ethos—a community where listeners and creators alike could reinvent themselves, hide behind virtual avatars, and interact through shared inside jokes.

From Internet Microgenres to Cultural Phenomenon: The Case of Blank Banshee

While early vaporwave focused on atmosphere and irony, Canadian artist Blank Banshee introduced a different dimension. His self-titled album Blank Banshee 0 (2012) and its successor Blank Banshee 1 (2013) layered classic vaporwave textures over hip-hop-inspired beats and digital rhythms. This fresh blend, dubbed “vapourtrap,” bridged vaporwave with broader electronic music trends and expanded its appeal far beyond its online roots.

Blank Banshee 0 became essential listening for a new wave of vaporwave fans. Its tracks, such as Eco Zones and Ammonia Clouds, combined catchy, crystalline melodies with subtle nods to early 3D computer graphics and virtual landscapes. Unlike the eerie slowness of earlier works, these songs pulse with energy, reflecting the fractured, accelerated pace of internet-era life.

Furthermore, Blank Banshee’s visual artwork—filled with neon gradients, pixelated objects, and references to early computer culture—cemented the importance of aesthetics within the vaporwave movement. He demonstrated how visuals and music could become inseparable, with each amplifying the other’s emotional resonance.

Mallsoft and Corporate Haze: Luxury Elite and Cosmic Collective

Another pillar in the vaporwave scene is Luxury Elite, an American producer who specializes in a substyle called “mallsoft.” While Floral Shoppe explores dreamy nostalgia, mallsoft tries to recreate the surreal emptiness of a deserted shopping mall late at night. The 2013 album World Class by Luxury Elite demonstrates this perfectly: samples of muzak, background chatter, and echoing footsteps are rearranged into tracks that feel both comforting and unsettling.

Albums like S1109, Late Night Delight (a collaboration with Saint Pepsi), and Class Act further solidified Luxury Elite’s reputation within the vaporwave canon. Her commitment to the “ambient mall” sound, combined with a dedication to cassette and vinyl releases, reinforced the genre’s ties to analog nostalgia and DIY artistry.

The broader vaporwave “collective” spirit—the idea that anyone can participate and contribute—also finds roots in the approach of producers like Luxury Elite. Using simple audio software and accessible tools, artists helped vaporwave flourish as an internet-driven, international scene. This open-door attitude encouraged thousands of creators worldwide, from amateur hobbyists to professional sound designers.

Dancing Through the Pixel Mist: Saint Pepsi, Yung Bae, and the Rise of Future Funk

As vaporwave splintered into fresh territories, Saint Pepsi (now known as Skylar Spence) emerged as a key figure in the rise of future funk. His 2013 release Hit Vibes captures the genre’s exuberance—layering disco, Japanese city pop, and sparkling samples into bright, energetic tracks. For many, Hit Vibes transformed future funk from an experimental curiosity into a summer dance party soundtrack.

Yung Bae soon followed, pushing the style further with a dazzling mix of city pop, funk, and jazz. His debut album Bae (2014) and following releases like Japanese Disco Edits (2015) rapidly gained global fandom. The duo’s approach marked a shift: instead of focusing entirely on nostalgia and irony, future funk artists drew listeners into pure celebration—sunshine grooves, infectious drumbeats, and a sense of collective joy.

Importantly, these artists helped vaporwave shed the image of a purely internet-based genre. Their music filled clubs, appeared in advertising, and found audiences as far away as Japan and Korea—demonstrating how vaporwave’s core ideas could adapt, morph, and thrive in different cultural contexts.

Virtual Memories and the DIY Archive: The Power of Community and Forgotten Gems

The history of vaporwave is incomplete without mentioning the countless lesser-known artists who populate its vast digital landscape. Names like Internet Club, Saint Pepsi, 猫 シ Corp. (Cat System Corp.), and death’s dynamic shroud each contributed vital albums and innovative techniques over the past decade. Projects like Rebirth, News at 11, and Faith in Persona carry forward the tradition of reassembling forgotten media into new audio experiences.

Online platforms such as Bandcamp, SoundCloud, and niche forums have been crucial to these artists’ development. They enable direct connection between creators and listeners, while the widespread adoption of digital distribution has preserved the ephemeral, ever-changing nature of vaporwave’s archive.

Moreover, the scene’s embrace of self-releasing, bootleg cassettes, and limited-edition vinyl has made vaporwave not just a sound, but a tactile experience for collectors and fans. This DIY spirit is more than nostalgia; it’s a celebration of creative freedom and a quiet rebellion against music industry conventions.

With each new release and every sample unearthed from the past, vaporwave continues to reinvent the art of collective memory. Its pioneers and their works invite listeners to wander through dreamlike soundscapes, rethinking not only how music is made, but also how it echoes in the digital age.

Hacking the Digital Canvas: How Vaporwave Engineers New Realities

Forging Nostalgia in the Digital Age

Vaporwave is a genre that lives and breathes through its relationship with technology. Unlike genres rooted in traditional instruments or live performance, vaporwave thrives in the digital realm—a product of home computers, basic audio software, and the vast treasure trove of online media. The earliest vaporwave pioneers were often bedroom producers working with modest resources. Instead of high-end studios, they wielded free or inexpensive digital tools like Audacity, FL Studio, or Ableton Live. These software programs allowed them to capture audio fragments, slow them down, pitch-shift vocals, and rearrange melodies—all with just a laptop and a pair of headphones.

This accessibility became a defining feature of the movement. Anyone with an internet connection could join in. No professional background or expensive gear was necessary—striking for an era in which electronic music had often been gated by expensive synths or complex setups. The lo-fi, sometimes “broken” quality of early vaporwave isn’t a flaw but a central part of its message. Compression artifacts, poor audio fidelity, and digital glitches are not just tolerated; they’re celebrated, calling attention to the artificiality of the source material.

Chopping, Pitching, and Time-Stretching: Manipulating the Source

At the heart of vaporwave creation lies the art of sampling. Producers begin by digging through obscure or overlooked media—elevator music, shopping channel soundtracks, corporate training videos, or Japanese city pop records—searching for sounds that conjure up a sense of faded glamour. Unlike typical hip hop sampling, which often chops a particular hook or beat for rhythmic effect, vaporwave stretches time itself. Tracks are often drastically slowed down, sometimes by half or more, creating a syrupy, dreamlike haze.

For example, on MACINTOSH PLUS’s landmark album Floral Shoppe, the original Diana Ross sample is slowed to the point of abstraction. Vocals become ghostly, shimmering echoes. Percussion, once tight and punchy, melts into ambient washes. Chopping—cutting source tracks into tiny repetitions—creates hypnotic loops that both anchor and disorient the listener. These manipulation techniques are simple to perform on most 21st-century audio programs, turning the computer into both a time machine and a kaleidoscope.

Pitch-shifting is another essential tool. Vocals may be raised or lowered by several steps, transforming them into alien croons or deep, robotic murmurs. This process often erases clear lyrical meaning, allowing the focus to shift toward texture and mood. Layering effects—like reverb, delay, or digital filters—intensifies the sensation that the music is echoing through the empty corridors of memory.

The Visual Language: Crafting Sound with Sight

Vaporwave’s technical identity isn’t just in what you hear. Its creators treat the visual aspect as an extension of the music. Album covers, YouTube visuals, and live performances are drenched in garish pastels, ancient computer fonts, pixel art, and references to Greco-Roman statues. To achieve this look, artists turn to tools like Photoshop, simple video editors, and even meme generators. There’s an intentional emphasis on low fidelity—glitches, VHS static, and pixelation remind us of a world before high-definition clarity.

This dialogue between sound and image is crucial. The music’s ghostly, half-remembered feel is amplified by visuals that look like artifacts from a half-forgotten internet. It’s not just aesthetic window-dressing; it affects the way we experience the music itself. When a vaporwave track is accompanied by looping, flickering visuals of 1980s malls or pixelated dolphins, it deepens the sense of nostalgia and unreality. Production is thus more than sound manipulation—it’s a holistic act, mixing auditory and visual reference points to tell a new kind of story.

The Internet as Both Stage and Studio

The rise of vaporwave is inseparable from the culture of online communities. To distribute their music, artists rarely turn to traditional record labels or radio stations. Instead, they upload tracks to platforms like Bandcamp, SoundCloud, and especially YouTube. Bandcamp became a favorite haunt, allowing for easy album releases, creative cover art, and direct connection between artists and listeners. YouTube played a special role by fostering a subculture of “visual albums,” looping GIFs, and user-made playlists, turning vaporwave releases into multimedia experiences.

Furthermore, the spread of vaporwave depended heavily on internet meme culture. Simple images—such as the pink Floral Shoppe bust or glitchy 1990s web graphics—became recognizable icons, reproduced, and remixed by fans worldwide. The fluid, remixable quality of both music and visuals encouraged active participation rather than passive consumption. This grassroots approach transformed vaporwave from a niche curiosity into a global phenomenon, as geographical barriers faded in the digital ether.

The Ethics and Controversies of Sampling

Vaporwave’s technical approach brings it into complicated territory with copyright law. The genre leans heavily on direct samples from existing copyrighted material—often using entire tracks without significant alteration. While this creative process shares roots with hip hop and collage art, vaporwave’s reliance on big, recognizable chunks of pre-existing music makes it especially legally ambiguous.

Some consider this part of the genre’s message: an artistic protest against strict intellectual property boundaries and a commentary on cultural recycling. Notably, few vaporwave artists have faced major lawsuits, partly because their releases tend to fly under the radar or are released for free. However, increased media attention and the genre’s growth have led to occasional track takedowns from platforms like YouTube. The tension between creative freedom and copyright protection remains unresolved—a central part of vaporwave’s underground character.

Global Adaptations and Hybridization

While vaporwave’s original toolkit emerged from affordable Western technology and U.S.-centric pop culture, its techniques have spread worldwide. In Japan, for example, vaporwave intersects with city pop and retro anime fandom. Producers in Russia, South America, and Europe infuse local references—be it Soviet-era muzak or ’90s Eurodance samples—into their own takes on the style. The tools remain largely the same: simple DAWs and image editors, freely available samples, a taste for digital decay.

What changes is the local flavor and the meaning behind the manipulations. In the U.S., slowing down mall music may evoke suburban ennui, while in Brazil, it might highlight the surreal aspects of global capitalism. The accessible nature of vaporwave’s sonic palette ensures that anyone can transform local nostalgia into something new, turning the genre into an endlessly adaptable set of production techniques and aesthetic codes.

By lowering the technical and economic barriers to entry, vaporwave encourages a constant stream of innovation and reinterpretation. The dialogue between software, sampled sounds, and visual imagination continues to evolve, as new artists push the boundaries with AI-generated art, virtual reality experiences, and beyond.

The spirit of experimentation that birthed vaporwave’s signature sound remains alive. As technology advances and new digital tools emerge, the genre’s creators are poised to uncover fresh ways to twist, recycle, and reimagine yesterday’s dreams for a new generation of listeners.

Echoes from the Digital Void: Why Vaporwave Matters to Modern Culture

The Internet’s Sonic Mirror: Reflecting a Generation’s Anxiety and Longing

At first glance, vaporwave might seem like a curious internet fad—music built from chopped and slowed pop samples, paired with pastel graphics and pixelated fonts. Yet beneath its dreamy surface, vaporwave stands as a cultural phenomenon that has captured the spirit of a generation shaped by rapid technological change and economic uncertainty. When MACINTOSH PLUS’s Floral Shoppe became a viral sensation in 2011, it wasn’t just the start of a new genre; it was the birth of a digital critique.

Vaporwave emerged at a time when the optimism of earlier decades had given way to questions about late capitalism, the commodification of everyday life, and the overwhelming presence of the digital. Its signature sound—the ghostly echoes of forgotten mall music and 1980s advertising—felt painfully familiar to millennials and Gen Z listeners. By recycling commercial jingles and Muzak, vaporwave artists asked their audience to re-examine the comforting yet hollow sounds of consumer culture. Each track plays like a memory loop, forcing us to confront the manufactured nostalgia that brands and media peddle relentlessly.

This cultural reflection isn’t accidental. Vaporwave intentionally blurs the boundaries between critique and celebration. The genre both mocks and mourns the mood of the late 20th century, highlighting how mall culture, corporate optimism, and shiny technological promises are now relics. The faded audio samples become metaphors for lost futures—and for the uncertainty of the present.

Screens, Memes, and Online Communities: Vaporwave’s Digital Life

Unlike classic genres that grew in physical spaces—bars, clubs, and local scenes—vaporwave found its home entirely online. The genre spread through platforms like Bandcamp, SoundCloud, and YouTube, where anyone could upload tracks, remix others, and share artwork instantly. This level of accessibility fueled a creative explosion, turning vaporwave into one of the first truly “internet-native” musical movements.

Virtual communities became the lifeblood of vaporwave’s evolution. Early discussion boards, Tumblr blogs, and Reddit threads connected anonymous producers from around the globe. These digital gathering spots were more than fan forums; they were laboratories for new sounds and aesthetics, where teenagers from Tokyo, Toronto, or São Paulo could influence each other’s work in real time. One moment, a Brazilian producer might share a dreamy edit inspired by Japanese city pop; minutes later, another artist in Europe might remix it with fragments of French elevator music.

Moreover, vaporwave artists and fans helped create a visual world as distinctive as the music itself. Neon gradients, VHS glitches, Roman busts, and Windows 95 icons became a common visual language. These images didn’t just evoke nostalgia—they recontextualized the detritus of the digital age, drawing attention to the beauty and absurdity found in everyday technology. In effect, vaporwave transformed the internet itself into a living collage, with music and images flowing seamlessly between platforms and continents.

Nostalgia as Political Commentary: Capitalism, Memory, and Ironic Distance

Vaporwave’s fascination with nostalgia isn’t just about revisiting childhood. The genre engages in a subtle but powerful critique of consumerism. By sampling corporate music, brand themes, and old commercials, vaporwave exposes the emptiness of mass-produced happiness. The dreamy, sometimes unsettling atmosphere of Floral Shoppe or Internet Club releases isn’t merely about remembering the past; it’s about questioning why that past feels so omnipresent—and who profits from its repetition.

Some academics have even argued that vaporwave embodies a form of “capitalist surrealism.” Tracks made from mall music—once designed to be ignored—return as objects of fascination and discomfort. These songs, stripped of their original context, highlight how pervasive and manipulative advertising soundscapes were. What once soothed shoppers now serves as an uncanny reminder of how deeply commercial messages have shaped collective memory.

This sense of irony flows through vaporwave culture. The genre delights in paradox, transforming what was once “background noise” into the foreground of artistic expression. Listeners are encouraged to simultaneously enjoy and critique their own nostalgia, to embrace both sentiment and cynicism. It’s this dual perspective that keeps vaporwave feeling relevant—even as other internet trends fade away.

Global Remixing: Crossing Borders with Style and Subculture

Vaporwave’s journey from obscure internet genre to global cultural force demonstrates how musical ideas can cross boundaries in the digital era. What began with American and Japanese pop samples quickly grew into an international exchange. Producers in Russia, South America, and Eastern Europe began remixing their own regional soundtracks, often blending vaporwave’s techniques with traditional music or local pop hits.

For example, Russian vaporwave artists have reworked themes from old Soviet cartoons or state-run stores, infusing them with the same eerie nostalgia found in Western releases. Similarly, creators in Brazil or Mexico have sampled local telenovelas, soap opera themes, or classic radio jingles. The result is a genre that reflects not just American “mall culture,” but the rise and fall of consumer dreams in different corners of the globe.

This adaptability is at the heart of vaporwave’s cultural influence. Each local scene puts its own spin on the genre, while still participating in a worldwide conversation about memory, technology, and longing. Fans in Poland might share album art with listeners in Korea, while artists in Italy adapt the vaporwave style to critique their own national institutions. The genre’s open-source approach—encouraging collaboration and remix rather than strict originality—makes it uniquely suited for the borderless world of the internet.

From Meme to Museum: Vaporwave’s Lasting Legacy

What began as an online joke—a few scattered tracks on obscure web forums—has left an indelible mark on mainstream and underground culture alike. Major pop and hip-hop artists have borrowed vaporwave’s visual style, from the pastel graphics to the surreal digital collages. Brands have flirted with the movement’s aesthetics to give themselves an ironic, retro edge. Even mainstream television and advertising have adopted vaporwave-inspired imagery for commercials and music videos.

At the same time, vaporwave has fueled new forms of artistic expression beyond music. Visual artists, fashion designers, and filmmakers draw upon its distinctive iconography, blending analog nostalgia with digital glitch. Exhibitions in contemporary art museums have explored the genre’s commentary on technology and memory, placing vaporwave alongside other avant-garde movements that challenge our relationship with media and the past.

Ultimately, vaporwave’s enduring power comes from its ability to speak to modern anxieties. It invites listeners to question the world around them—to look for meaning in the disposable, and to find beauty in obsolescence. As people navigate lives increasingly shaped by algorithms and information overload, the ghostly sounds and surreal images of vaporwave continue to resonate—a soundtrack for an age haunted by its own digital reflections. And as the internet reinvents itself in new waves and platforms, vaporwave stands as a reminder that even the most fleeting online subculture can echo through real life, reshaping how society remembers, creates, and dreams.

From Bedroom Monitors to Virtual Stages: Vaporwave’s Unexpected Performance Revolution

From Isolation to Connection: Vaporwave’s Unconventional Live Roots

Unlike most music genres, vaporwave was never conceived with packed clubs or bustling festival grounds in mind. Its origins are deeply digital—shaped by internet message boards and anonymous file-sharing, not live sets or traditional concerts. In fact, many early vaporwave creators, including Vektroid and those inspired by her work, operated in deliberate anonymity, choosing cryptic online monikers over star personas.

This approach wasn’t accidental. Vaporwave’s foundations rest on repurposing found sounds, using lo-fi aesthetics, and dismantling the lines between creator and consumer. Because much of this music was built entirely on laptops and aged samples rather than live instruments or rehearsed performances, early fans experienced it in solitude—through headphones at home, late-night YouTube sessions, or buried in endless SoundCloud playlists.

However, as the scene gained momentum and cultivated a devoted following, a new kind of “live” culture slowly began to emerge. This shift didn’t come from flashy arena shows but from online communities that blurred the barrier between artist and audience. Discussion threads became real-time feedback loops, and livestreams offered a sense of shared experience despite physical distance. In this way, vaporwave’s initial live context was paradoxically more social than it seemed—a digital gathering of like-minded listeners separated by thousands of miles but united by the glow of their screens.

The Birth of the Virtual Party: Livestreams, Festivals, and Online Gatherings

By the mid-2010s, advances in streaming technology set the stage for vaporwave’s distinct take on performance. Platforms like Twitch, YouTube Live, and even Discord servers became makeshift venues. Here, artists would curate virtual DJ sets, share unreleased tracks, or host listening parties for album premieres. The mood was often intimate and experimental—audiences might watch an artist manipulate obscure 1980s infomercial clips in real time, or interact through chat while vaporwave visuals flickered onscreen.

One of the most transformative moments for the genre came with the rise of online festivals such as 100% ElectroniCON, organized by George Clanton and the label 100% Electronica. First held in person in Brooklyn in 2019, ElectroniCON quickly adapted to the realities of the global COVID-19 pandemic by pivoting to virtual editions. These events reimagined “live” for the vaporwave community: global lineups, interactive sets, and fan chats all delivered through immersive digital platforms. Fans were able to tune in from Tokyo, London, São Paulo, or anywhere the internet reached—experiencing a show together while still sitting in their own rooms.

Beyond ElectroniCON, a wave of online-only events blossomed. Virtual raves hosted on Twitch attracted hundreds, sometimes thousands, of viewers who came not just for the music, but for the playful, pixelated environments that recalled vaporwave’s iconic visual aesthetics. Audience members expressed themselves through retro avatars, custom emotes, or even by decorating their virtual “rooms,” cementing vaporwave’s reputation as a genre uniquely suited to digital performance.

The Physical World Reimagined: Vaporwave’s Journey into Traditional Venues

While vaporwave’s heart may belong to the cyberspace, the genre has also ventured into physical performance. This transition posed unique challenges. How does a genre built from carefully edited samples and nostalgic internet visuals translate to a nightclub or concert hall? For many years, most vaporwave tracks weren’t performed live at all—they were curated via DJ sets, with artists mixing their own tracks alongside obscure samples and companion genres like future funk or synthwave.

Innovators such as George Clanton—who also records under the alias ESPIRIT 空想—helped bridge the gap. Clanton incorporated live vocals, analog synths, and on-stage improvisation, developing shows that blended the genre’s signature chopped-and-screwed soundscapes with a performative flair reminiscent of classic electronic artists. These concerts attracted crowds looking for something both nostalgic and novel. Instead of lasers and arena theatrics, attendees found themselves immersed in hazy projections of obsolete technology, VHS static, and looping animations.

Internationally, vaporwave-themed events have popped up in cities as varied as Los Angeles, Berlin, and Tokyo. In Japan, for instance, underground gatherings sometimes blur the boundaries between art exhibition and dance party, with installations featuring old computers, cathode ray TVs, and interactive video projections. The music is only part of the sensory experience—it’s accompanied by visual artists who manipulate new and old media to create spaces awash in pastel hues and neon lights.

Still, even in these in-person gatherings, the spirit remains deeply communal and rooted in internet culture. Merchandise stalls offer cassettes, floppy disks, and 3D-printed artifacts. Fans show up in retro track jackets or ironic polos, embodying the aesthetic as much as the sound. Unlike the spectacle of mainstream pop concerts, vaporwave’s events often feel more like niche conventions where shared references and in-jokes animate the crowd.

The Power of Screens: Visuals, Interactivity, and Performance Art

No exploration of vaporwave’s live dimension would be complete without considering its visual identity. The genre’s performances are as much about what the audience sees as what they hear. Live artists invest heavily in visual storytelling—projecting collages of low-res graphics, Japanese cityscapes, computer interface windows, and surreal 3D renderings. These visuals aren’t background noise; they’re integral to the experience, amplifying the sense of distorted nostalgia that defines vaporwave.

Interactivity is another key element. Some events invite viewers to vote on visual backdrops or submit their own samples in real time, turning passive listeners into co-creators. Others feature live “VJing,” where performers remix video content on the fly to sync with evolving soundscapes. This creates a dynamic atmosphere that evolves from set to set, making each performance feel unique and ephemeral—a digital happening more than a fixed concert.

Moreover, accessibility sits at the core of vaporwave’s live ethos. While mainstream live music can be limited by ticket prices, travel, or exclusivity, vaporwave gatherings—especially online—often prioritize openness. Many events are pay-what-you-can or even free, with donations supporting independent labels and artists. Fans from anywhere and of any age can participate, bringing together an incredibly diverse set of listeners that’s rare for niche musical styles.

Looking Further: The Future of Vaporwave Performance

As technology continues to evolve, so too do the ways in which vaporwave can be experienced live. Virtual reality concerts, interactive multiplayer events, and augmented reality installations are already beginning to shape the next chapter of the genre’s performance culture. These platforms promise even deeper immersion, allowing audiences not just to watch but to explore dreamlike vaporwave worlds together.

At the heart of this evolution, however, remains vaporwave’s original promise—a space where music, memory, and shared digital experience collide. Whether it’s through pixelated avatars dancing in a virtual club or fans gathering IRL to swap homemade cassette tapes, vaporwave’s live culture continues to upend expectations of what performance can be.

Rather than fading into internet obscurity, vaporwave’s fusion of online and offline, visual and sonic, has turned it into one of the most dynamic and approachable genres for both artists and fans. The journey from bedroom monitors to virtual stages shows no sign of slowing, inviting anyone with a screen—and a sense of curiosity—to join in and help shape what comes next.

From Obscure Online Experiment to Global Aesthetic: Vaporwave’s Unlikely Journey

The Birth of Vaporwave: Collision of DIY Culture and Internet Nostalgia

Vaporwave’s beginnings can be traced directly to the early 2010s, a time when internet culture was rapidly evolving and digital tools were becoming accessible to wider audiences. It wasn’t the product of music industry machinery or established scenes, but the outgrowth of a do-it-yourself ethos born on platforms like Tumblr, Bandcamp, and Reddit. Aspiring musicians—often with little formal training—began to explore the forgotten corners of 1980s and 1990s pop culture, digging for elevator music, corporate training videos, and obscure Japanese city pop records.

One of the earliest and most influential figures, Daniel Lopatin (better known as Oneohtrix Point Never), played a crucial role with his 2010 album Chuck Person’s Eccojams Vol. 1. This release set the stage for vaporwave’s defining methods, including the chopping, looping, and slowing down of recognizable pop snippets until they became unrecognizable, dreamlike echoes. Eccojams itself was not meant as a manifesto, yet it opened the door for others like Vektroid (also known as MACINTOSH PLUS) to push the aesthetic further and develop the genre’s trademark mood.

It’s important to recognize just how decentralized the movement was from the outset. Unlike traditional scenes centered around clubs, record shops, or concert halls, vaporwave thrived in digital commons. Artists interacted anonymously, using aliases and profile pictures instead of headshots. This anonymity and collective creativity allowed vaporwave to become more than a genre—it became a digital folk art for a restless generation.

Viral Liftoff: The Floral Shoppe Phenomenon and Meme Culture

By 2011, vaporwave achieved widespread attention through MACINTOSH PLUS’s Floral Shoppe. The track リサフランク420 / 現代のコンピュー spread rapidly across YouTube, bolstered by surreal imagery, Japanese text, and pastel-heavy visuals. The video’s popularity was driven not just by the catchy, chopped-and-screwed sample from Diana Ross, but by how seamlessly it fit into meme culture. Users remixed the visuals and sounds, creating variations and in-jokes that helped Floral Shoppe become an online sensation.

This viral success marked a turning point. Vaporwave’s initial community of niche internet users had created something that resonated more broadly, even if that resonance was often tongue-in-cheek. Internet humor, aesthetic parody, and sincere nostalgia mixed in unpredictable ways. Suddenly, vaporwave’s signature look—Roman busts, glitchy graphics, hot pinks and teals—was everywhere from clothing brands to indie video games.

By embracing its meme-driven distribution, vaporwave displayed a unique ability to mutate and spread. The genre was never static or monolithic; every repost, remix, or new sound added layers to its evolving legacy.

Shifting Tides: Fractures, Evolutions, and Subgenre Bloom

As attention around vaporwave surged, so did its diversity. Throughout the early to mid-2010s, a range of subgenres appeared, each building on or reacting against the original formula. Some artists leaned into vaporwave’s dreamy nostalgia, while others used the sound as a critique of consumer anxieties and digital alienation.

Future Funk emerged as an offshoot, fueling upbeat remixes of Japanese city pop and disco. Its energetic rhythms and positive tone broadened the appeal of vaporwave, giving listeners a sound that felt as danceable as it was nostalgic. On the other side of the spectrum, Mallsoft doubled down on the “empty mall ambience,” offering longer, more immersive compositions that mimicked the experience of wandering through deserted retail spaces. This emphasis on environmental sound and atmosphere showed how vaporwave could evoke complex emotions—comfort, sadness, boredom, or even the eerie calm of post-capitalist decay.

A more dystopian twist emerged with Hardvapour, a subgenre that replaced soft synths and smooth samples with aggressive beats, abrasive distortion, and bleak themes. Originating on platforms like Bandcamp, it turned vaporwave’s sense of nostalgia into something darker and more confrontational, reflecting the anxieties of a world saturated in digital noise and economic instability.

These evolutions highlight vaporwave’s remarkable flexibility as a genre. It could function as earnest nostalgia, biting satire, ambient soundtrack, or club-ready remix—sometimes all at once.

International Spread: Crossing Borders and Blending Cultures

The global reach of vaporwave cannot be overstated. Early on, Japanese cultural influences were already central, from the frequent use of Japanese characters to the sampling of city pop and J-pop gems. As the genre proliferated, producers from Brazil, Russia, France, and South Korea joined in, infusing their own cultural icons, television snippets, and commercial jingles into the mix. In Brazil, artists drew from bossa nova and local television ads; in Russia, Soviet-era music and aesthetics inspired a wave of ironic, retro-futurist vaporwave releases.

Online spaces enabled these international exchanges. Producers formed collaborations without ever meeting face to face, trading files and techniques through forums, Discord servers, and social media threads. Entire subcultures sprang up around national takes on vaporwave, illustrating how a genre rooted in Western consumer nostalgia could be reinterpreted through different cultural lenses.

This spirit of continuous remixing and cross-pollination is crucial to understanding why vaporwave survived long past its “meme” peak. It became a framework, a set of tools and visual cues—plastic palm trees, neon grids, swirling VHS static—that anyone, anywhere, could use to say something about their own history with technology and memory.

The Present: From Internet Joke to Enduring Influence

By the late 2010s, many critics had predicted that vaporwave would fade as quickly as it arrived. Yet the opposite proved true. Whether as a springboard for experimental music, a visual branding toolkit, or a political statement on digital fatigue, vaporwave’s DNA has embedded itself across digital culture.

Artists like Saint Pepsi (now known as Skylar Spence) and 100% Electronica label co-founder George Clanton have pushed the sound into new territories, blending pop songwriting with processed samples. Massive online festivals—such as 100% ElectroniCON—drew thousands of fans eager to celebrate not only the original sound but the community-driven, tongue-in-cheek atmosphere that vaporwave championed. Independent record labels specialized in cassette releases, pulling an entire generation of listeners back to analog formats as a new kind of retro rebellion.

It’s in these moments—between irony and sincerity, parody and genuine emotional connection—that vaporwave’s legacy thrives. Never just a genre, vaporwave is both a historical movement and a living, breathing aesthetic that continues to shape how we visualize and hear the digital world.

As streaming services, hyperactive social media, and the endless churn of internet trends reshape music faster than ever, vaporwave’s story shows how even the most fleeting online experiments can take on lives of their own. Each new generation finds fresh ways to turn digital leftovers and nostalgic fragments into something resonant, playful, and, unexpectedly, timeless.

Digital Ghosts and Shifting Paradigms: Vaporwave’s Lasting Mark on Music and Culture

The Ripples of a Genre That Never Meant to Last

When vaporwave first surfaced in the early 2010s, even its most dedicated creators didn’t anticipate its endurance. Built on a foundation of chopped samples and retro graphics, the movement was intentionally fleeting—almost a parody of its own digital ephemera. Yet, more than a decade later, the shadows of MACINTOSH PLUS and Oneohtrix Point Never still stretch across today’s musical and visual landscape.

Vaporwave’s output was often distributed freely in obscure corners of the internet, with little expectation of long-term impact. Ironically, this low-key approach laid the groundwork for its unusual persistence. Tracks like リサフランク420 / 現代のコンピュー from Floral Shoppe, once shared in meme threads and lo-fi YouTube playlists, have become cultural touchstones for digital natives. Familiarity with vaporwave’s sound—a slow-motion re-imagining of commercial music and background tunes—now signals an awareness of internet culture’s deeper layers. In this way, what began as a genre that playfully critiqued consumerism became a subtle, ongoing force in online self-expression.

Furthermore, vaporwave’s aesthetic and philosophy proved surprisingly adaptable, representing both irony and genuine longing. These dual aspects continue to influence the sensibilities of creators in music, visual art, and fashion who aim to interpret an uneasy blend of nostalgia and critique.

The Sound of a Generation: Influence Across Musical Genres

Vaporwave altered the way a generation approaches music production. Before its rise, few genres encouraged such direct engagement with pre-existing sound materials, treating the past as raw material for transformation. While hip-hop and electronic music had long employed sampling, vaporwave’s philosophical stance was distinct—it wasn’t just about reusing beats or hooks. Instead, it recontextualized entire moods and forgotten commercial soundscapes. By slowing down easy-listening tracks and corporate jingles, vaporwave forced listeners to confront the emotional emptiness and beauty embedded in everyday audio clutter.

The genre’s low-budget accessibility transformed thousands of listeners into producers. Software like Audacity and FL Studio, rather than traditional instruments, enabled music creation at a fraction of the usual cost. As a result, countless young musicians found their voices in what initially seemed like a joke or an experiment. For example, microgenres such as future funk—pioneered by artists like Yung Bae—and mallsoft borrowed vaporwave’s foundational techniques and transported them into exciting new directions. The playful manipulation of 80s city pop samples in future funk brought an upbeat energy to the genre’s signature dreaminess, while mallsoft deepened the meditative reflection on commercial spaces.

Moreover, vaporwave’s bold approach to tempo alteration, looping, and pitch shifting has echoed throughout contemporary pop and indie. Its influence is audible in the work of artists far outside its original scene, including James Ferraro, whose album Far Side Virtual twisted everyday digital noises into high-concept sound art. Even mainstream artists have experimented with vaporwave-esque aesthetics, blending washed-out synths and retro textures into their singles and videos.

Digital Aesthetics Redefined: Far Beyond Music

The legacy of vaporwave dramatically extends into visual culture. Early on, vaporwave visuals—think pastel grids, glitch art, ancient statues, and Japanese text—were as integral to the genre as the music itself. These images, recycled endlessly on Tumblr, Instagram, and album covers, spawned entire subcultures. The popularity of vaporwave-style designs signaled a shift toward what some called “remix culture.” Here, not only sounds but also visual codes were ripped from their contexts, scrambled, and re-presented in ironic or poignant forms.

Brands and designers quickly took notice. Advertising campaigns and clothing lines in the late 2010s adopted vaporwave’s hyperreal colors and absurdist digital motifs to speak directly to internet-savvy customers. Even major fashion houses and tech start-ups sought to co-opt the genre’s dreamlike palette in their branding, hoping to communicate a sense of hip, knowing nostalgia. As a result, vaporwave visuals entered the mainstream far faster than anyone anticipated, outlasting most other short-lived internet art trends.

This broad visual reach has also fueled ongoing debates about authenticity in art. With so many vaporwave motifs absorbed by big corporations, the genre’s community continues to wrestle with paradoxes: Can a movement that began as a parody of commercialism survive its own commercialization? This tension itself has become part of vaporwave’s identity. Each new adaptation invites both fresh creativity and pointed commentary within the genre’s fiercely independent circles.

The Hidden Architects of Online Identity

Vaporwave pioneers shaped more than just style; they inspired new forms of collective identity building online. In its early years, vaporwave flourished inside micro-communities on platforms like Reddit, Bandcamp, and Discord. These spaces prized anonymity and played with alter-egos—Saint Pepsi becoming Skylar Spence, or Vektroid cycling through a maze of cryptic pseudonyms. Instead of celebrity, these artists celebrated the collective remixing of culture.

This approach resonated deeply in an era when digital interaction was rapidly replacing face-to-face connection. Vaporwave’s culture of remixing, collaboration, and shared inside jokes became a coping strategy for navigating online life’s fragmentation. User-generated music videos, vaporwave-inspired memes, and shared playlists fostered communities around a shared aesthetic language. For many young listeners worldwide, adopting a vaporwave avatar or curating playlists provided a sense of belonging amid the anonymity of the web.

At the same time, the genre’s blurred lines between artist and audience mirrored larger trends in participatory digital culture. With barriers to entry so low, anyone could transform into a vaporwave creator overnight. This emphasis on community creation, rather than passive consumption, anticipated later movements in lo-fi hip-hop, plunderphonics, and even TikTok audio memes.

Enduring Echoes: Vaporwave’s Surprising Place in the Cultural Imagination

Few predicted the impact of a genre forged in online obscurity and built on the ruins of mass culture. Yet vaporwave continues to haunt the global imagination as both a relic and a messenger of the hyper-digital era. Remnants of its sound palette—echoing synths, slowed vocals, glimmering pads—surface regularly in playlists, YouTube backgrounds, and boutique record labels from Tokyo to Berlin.

Academic attention, once reserved for more traditional or “serious” music, now considers vaporwave a legitimate subject. Scholars and journalists analyze it as a mirror for society’s relationship with capitalism, technology, and longing for lost futures. This intellectual spotlight has inspired more artists to take vaporwave’s tropes and use them as tools for cultural criticism, personal expression, or playful subversion.

Looking forward, vaporwave’s ethos of recontextualization and communal identity-building invites new generations to reimagine their digital environment. As technology continues to blur the boundaries between real and virtual worlds, vaporwave’s legacy lives on wherever listeners interrogate, remix, and reinvent the sounds of their time. The echoes of vaporwave remind us that even the most fleeting internet trends can leave behind a deep and enduring resonance.