Why the 1950s Still Echo Today

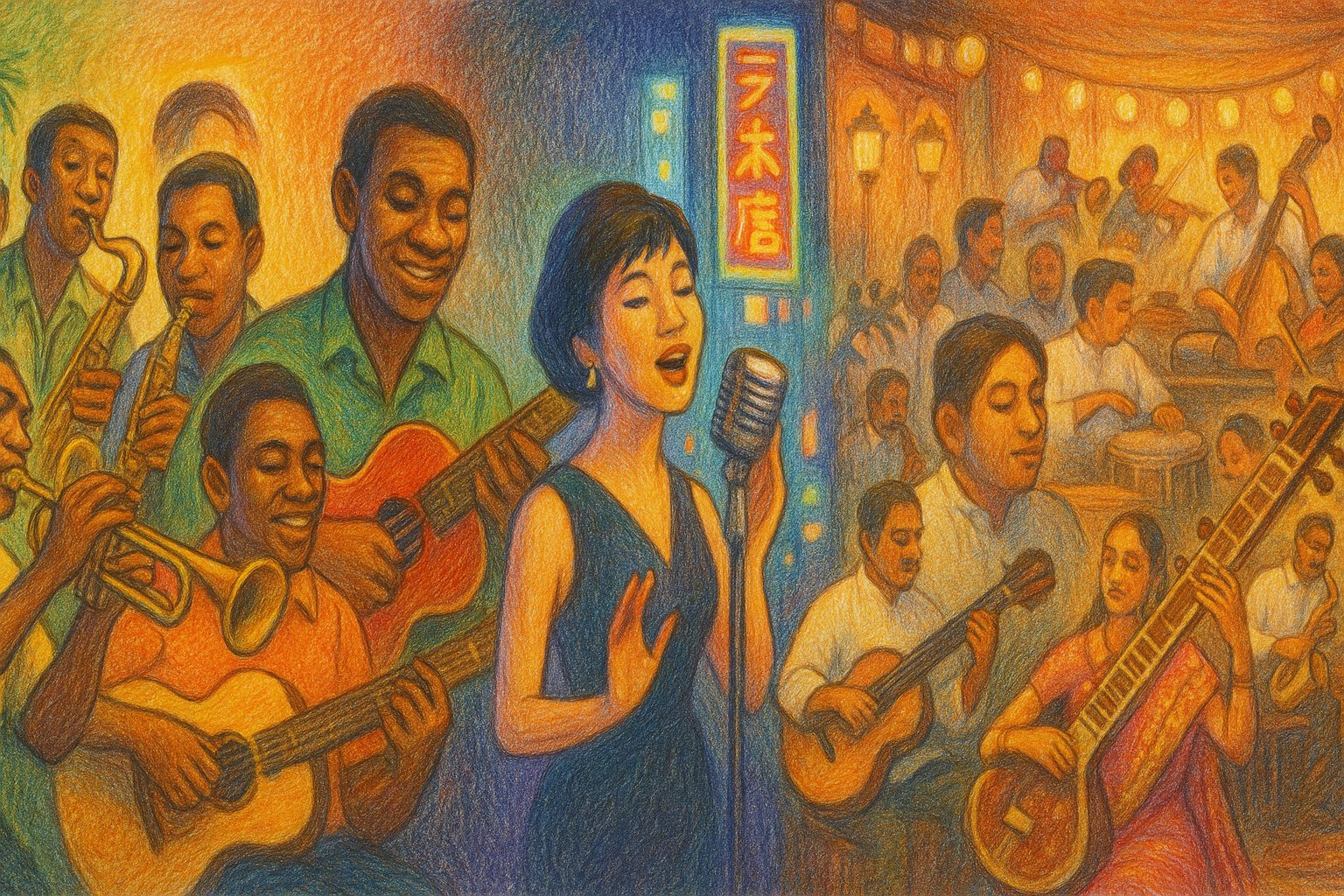

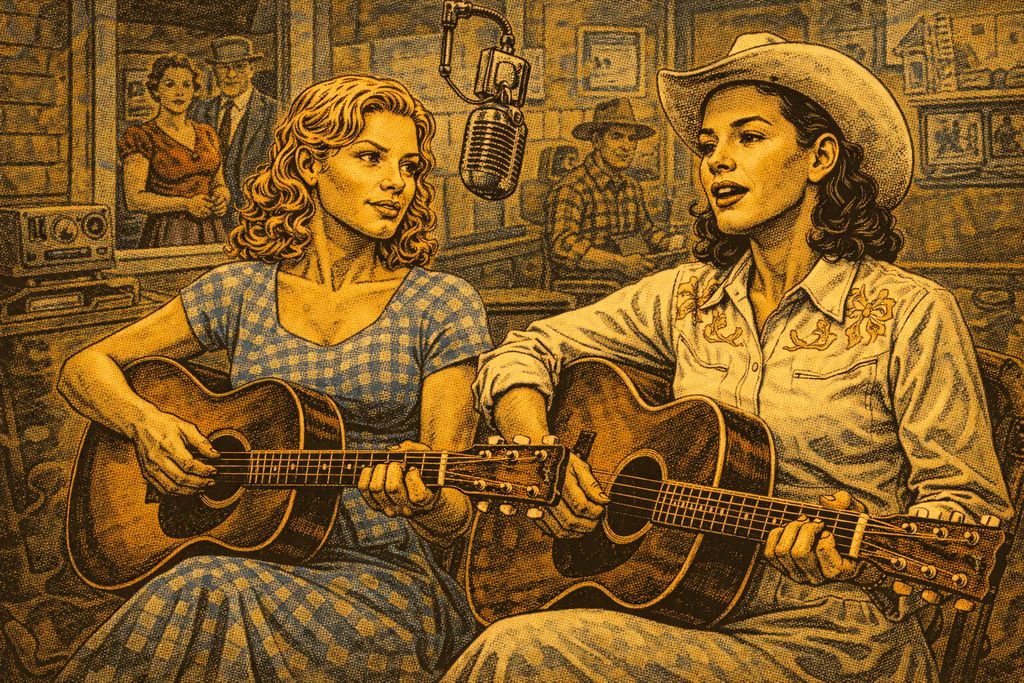

The 1950s didn’t just produce new sounds—they reshaped how music lived in the world. After years of war and uncertainty, everyday life was changing. Cities grew, industries expanded, and a new sense of possibility emerged. That possibility wasn’t evenly shared, but it was deeply felt—especially by young people who, for the first time, saw themselves as a distinct audience with their own tastes and desires. Music became their language.

Yet the decade was also defined by division. Race, class, and gender determined who was heard, seen, and paid. The sounds pouring from radios, jukeboxes, and clubs carried both freedom and constraint—joy and connection alongside the inequalities of the society that produced them.

This story begins not with stars or scandals, but with context: the social conditions, media structures, and everyday realities that allowed 1950s music to emerge, spread, and matter so deeply.

Post-War America: A New Generation Finds Its Voice

When the Second World War ended, everyday life in much of the Western world entered a period of rapid and uneven transformation. In the United States, industrial growth and rising wages brought new forms of stability to many families. Large parts of Europe were still rebuilding. Homes filled with new appliances. Suburbs expanded. Leisure time slowly became part of ordinary life rather than a rare luxury. Music followed these shifts closely. It was not a passive soundtrack, but an active participant in changing social rhythms.

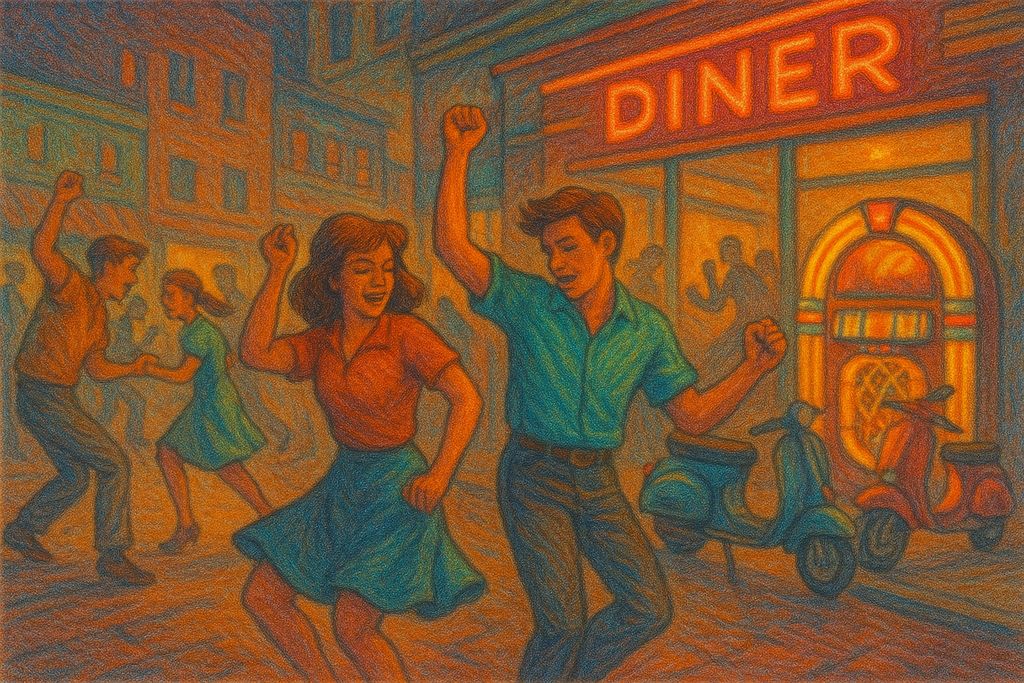

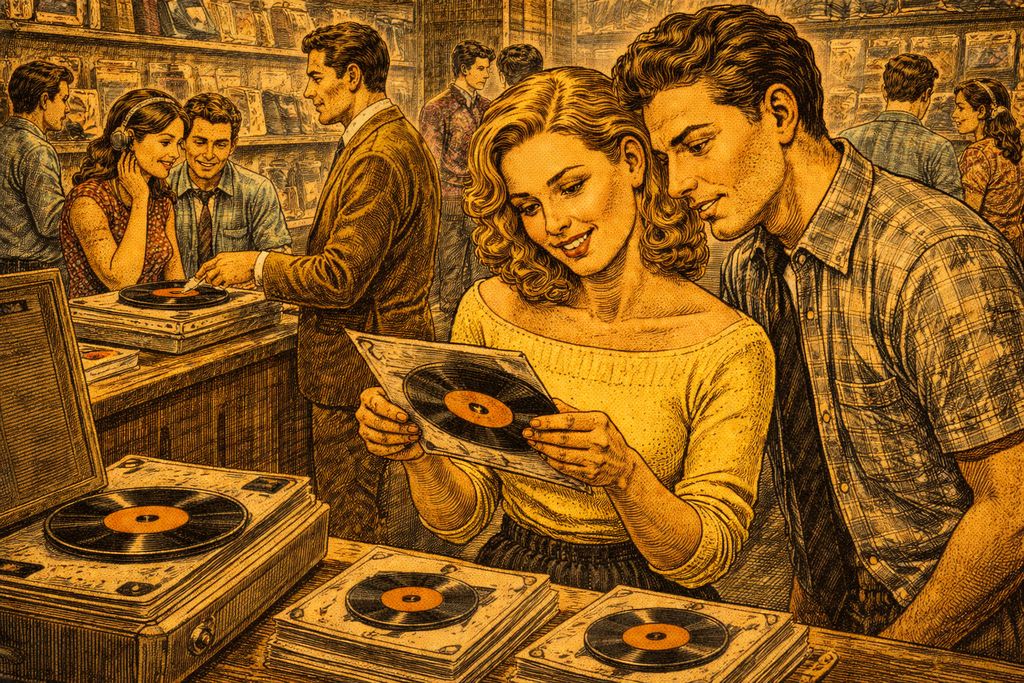

One of the most significant developments of the decade was the emergence of teenagers as a distinct social and economic group. For the first time, young people had modest but meaningful disposable income and fewer immediate responsibilities, fostering a growing sense that their preferences mattered. Record companies, radio stations, and advertisers noticed quickly. Singles were priced for impulse buying, while jukeboxes were stocked with songs that spoke directly to youthful moods, encouraging performers to aim their image and sound toward this new audience.

This shift did not erase older listeners. Adult audiences remained loyal to orchestral pop, jazz, and traditional vocal music. They often experienced these through the long-playing album, which had been introduced by Columbia Records in June 1948. What changed was the coexistence of markets. A teenager buying a 45 rpm single, first introduced by RCA Victor in March 1949, and an adult listening to a full LP were participating in the same musical economy. They did so for different emotional reasons. The industry learned to balance immediacy and intimacy. It learned to balance excitement and reassurance.

Economic growth also shaped where music was heard. Dance halls, clubs, churches, cinemas, and living rooms all played distinct roles. Radios were no longer rare objects. They were fixtures in kitchens and bedrooms. They turned private spaces into points of contact with a wider cultural world. At the same time, access remained unequal. For many Black Americans, economic opportunity was limited by segregation—a reality that persisted even as their music fueled much of the decade’s innovation. Migration from rural areas to cities intensified these contradictions, bringing new sounds into urban centers while exposing artists to fresh pressures and possibilities.

Youth culture in the 1950s was not yet a unified movement. It was tentative, curious, and often contested by parents, educators, and religious leaders. Music became a safe but powerful outlet for that tension. Songs allowed young listeners to explore desire, restlessness, and belonging without fully naming them. In doing so, they created a feedback loop between audience and artist. This loop would soon reshape popular music entirely.

Radio, Records, and the Birth of Mass Culture

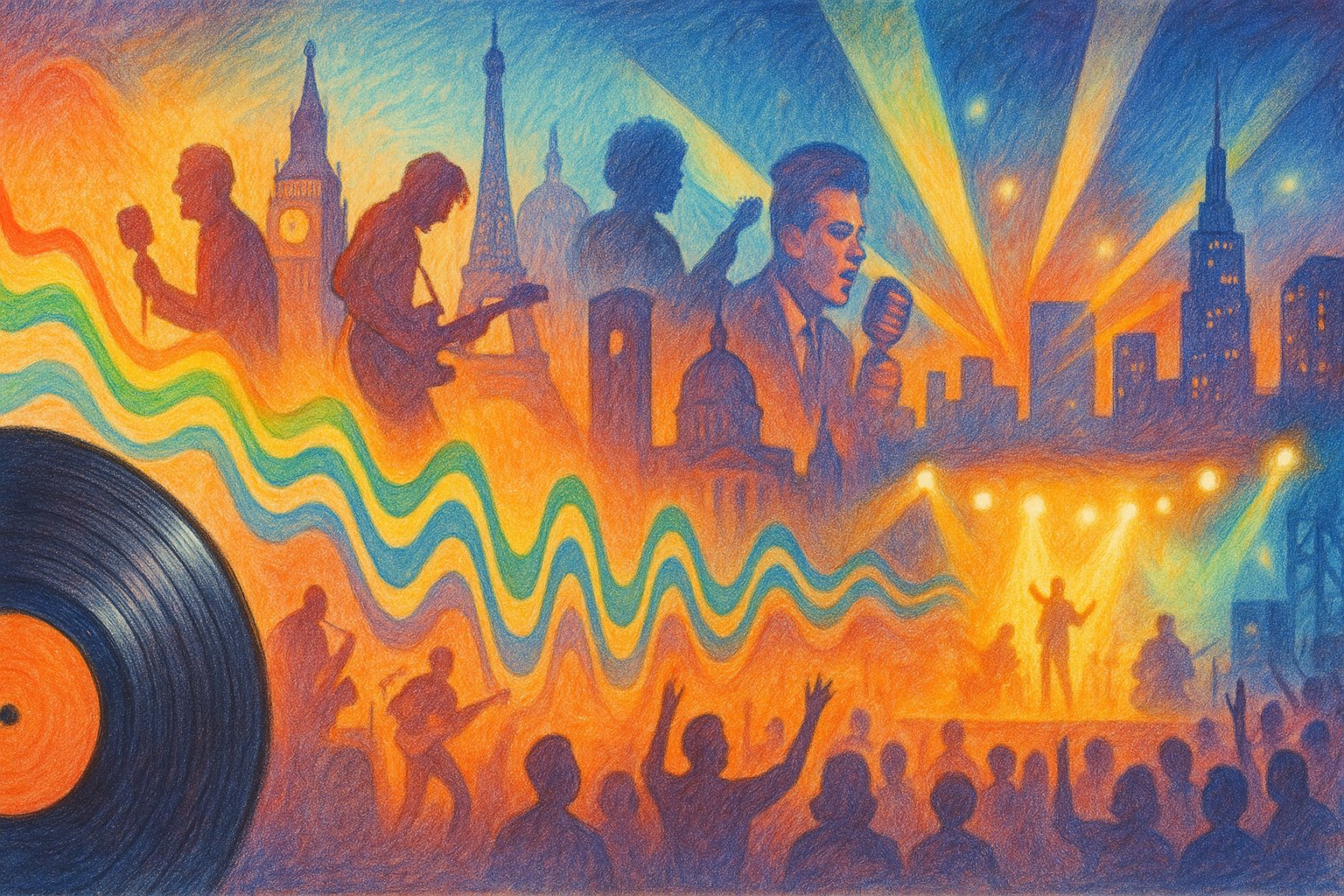

In the 1950s, music spread at a speed that would have been unimaginable only a decade earlier. Radio was a central force behind this change. AM stations reached deep into homes, cars, diners, and workplaces. They shaped daily routines and shared listening experiences. For many listeners, the radio did more than entertain; it created familiarity, repetition, and trust, making a frequently heard song feel like a companion even if the artist behind it remained distant or unknown.

At the same time, the record industry was refining its formats. The 45 rpm single and the long-playing LP transformed how music was consumed. Singles favored immediacy. They were cheap, portable, and ideal for jukeboxes. These became social hubs in cafés and bars. The LP, by contrast, invited attention and patience. Albums such as In the Wee Small Hours by Frank Sinatra showed that popular music could sustain a mood across an entire record. This encouraged listening as an emotional experience rather than background noise.

Radio playlists and record sales began to reinforce each other. DJs held enormous influence. They often acted as cultural translators between artists and audiences. A supportive disc jockey could break a record nationally. Silence on the airwaves could stall a career. This power imbalance would later spark public controversy. However, in the early years it simply shaped how tastes were formed. For young listeners, radio personalities felt approachable, even personal. This lent authority to the music they introduced.

Record labels adapted quickly. Independent companies such as Chess Records and Atlantic Records focused on regional sounds and emerging artists, often taking creative risks that larger companies avoided. Their success pushed major labels to pay closer attention to rhythm and blues, vocal groups, and early rock and roll. The boundaries between genres remained firm on paper, but they blurred in practice as songs crossed charts and audiences.

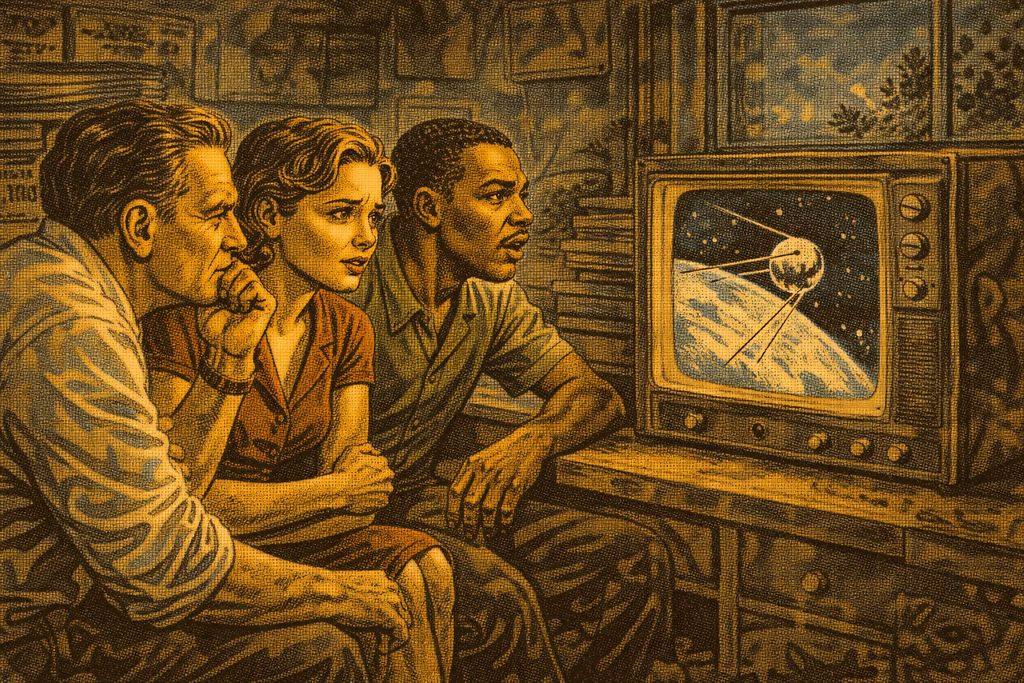

Mass media also shaped image. Artists were not only heard but increasingly seen, whether in publicity photos, film appearances, or early television broadcasts. Visual presentation began to matter almost as much as sound. A performer’s voice, clothing, posture, and perceived attitude all contributed to how music was received. This shift placed new pressure on musicians, particularly those whose appearance challenged social norms.

By the end of the decade, radio and records had created a shared musical language across vast distances. Music no longer belonged only to local scenes or live venues. It traveled easily, carrying with it both the promise of connection and the weight of industry control—weight that fell unevenly across a divided nation.

Segregation and Sound: Music in a Divided America

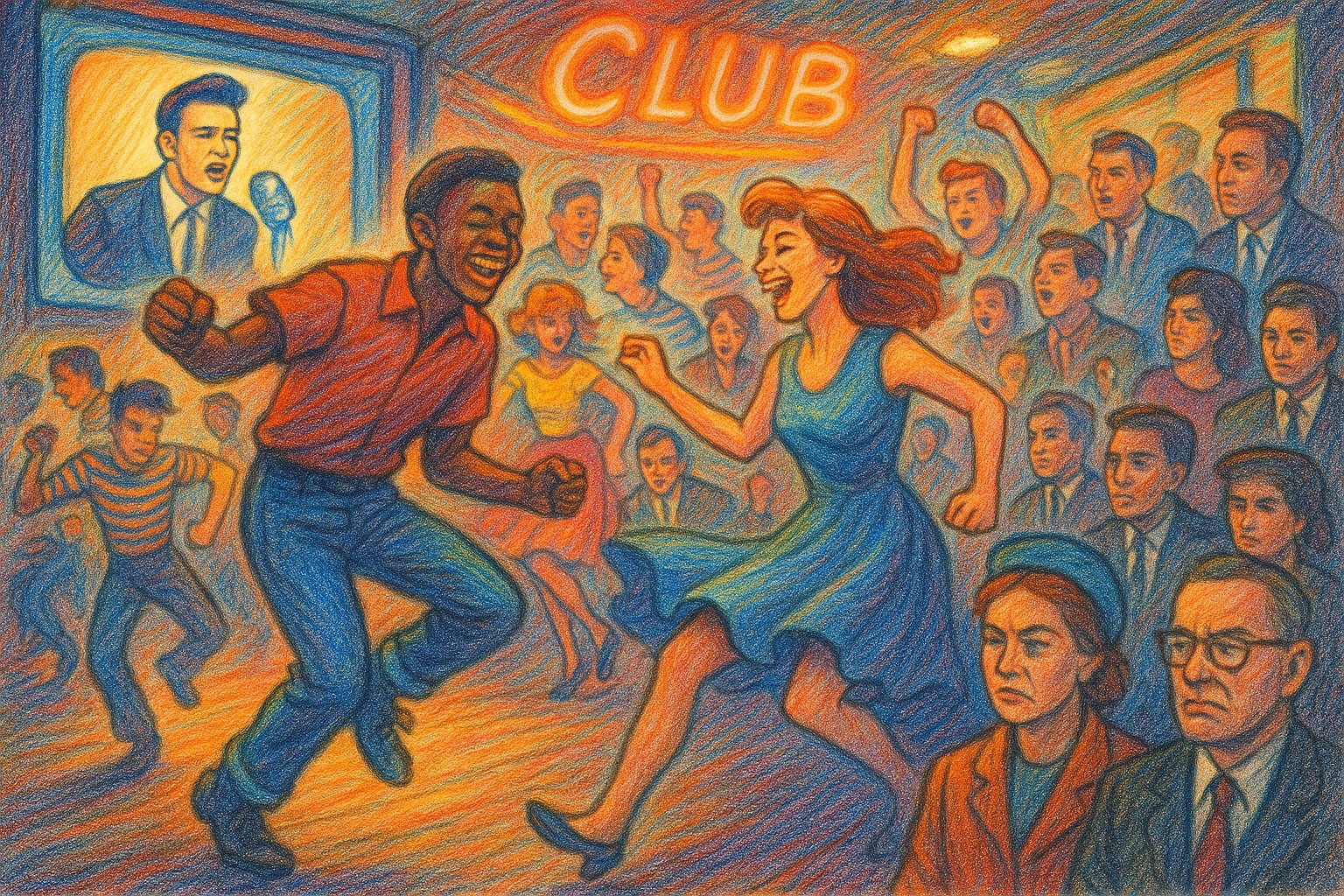

That shared language, however, carried contradictions. Music in the 1950s moved across racial boundaries more freely than almost any other part of American life. However, it did so within a society still rigidly shaped by segregation. Jim Crow laws governed daily existence in much of the country. They determined where people could live, work, travel, and perform. These realities were not separate from music. They shaped who could access studios, who could tour safely, and who was allowed to appear on certain radio stations or television programs.

Black musicians were at the center of many of the decade’s most important innovations. Blues, rhythm and blues, gospel, and jazz provided much of the rhythmic, vocal, and emotional language that would soon define popular music more broadly. Artists such as Ray Charles, Ruth Brown, and Muddy Waters built careers that were both artistically groundbreaking and structurally constrained. Their records sold widely. However, their opportunities were often limited by race-based marketing, segregated venues, and unequal contracts.

The record industry mirrored these divisions. Charts were separated into categories such as “race records” or rhythm and blues, even when the same songs were being purchased and enjoyed by white teenagers. Radio stations followed similar patterns. Some DJs quietly crossed these lines, introducing Black music to wider audiences late at night or under coded language. Others enforced them strictly, reinforcing the idea that certain sounds belonged to certain people.

Touring exposed these contradictions most sharply. Black performers traveling through the South faced constant uncertainty, relying on informal networks to find safe lodging and food. Even successful artists could be denied access to hotels or forced to enter venues through back doors. At the same time, white artists who recorded material rooted in Black musical traditions often encountered fewer obstacles, receiving broader promotion and more mainstream exposure.

Despite these barriers, music created moments of contact that were rare elsewhere. Integrated audiences gathered around jukeboxes, radios, and dance floors. They sometimes did so without fully realizing how unusual this was. Songs crossed racial boundaries before laws and institutions did. This did not erase inequality. It revealed its fragility.

The American music landscape of the 1950s was therefore defined by tension. Creativity flourished alongside restriction. Recognition and exploitation existed side by side. Understanding this dynamic is essential. It is not about reducing the decade to injustice alone. It is about recognizing how deeply social structures shaped the sound of the era. It is about understanding how they shaped the lives of those who created it.

Teenagers: The New Force Driving Music

By the middle of the 1950s, the music industry had come to a clear realization. Teenagers were no longer just listeners. They were consumers, tastemakers, and cultural drivers. This shift did not happen overnight or with much sensitivity. It emerged from a simple observation. Young people were buying records in growing numbers. They were spending time around jukeboxes. They were forming emotional attachments to songs that spoke directly to their experience.

The 45 rpm single was perfectly suited to this new market. It was affordable and easy to replace. It encouraged repeated purchases and fast-moving trends. A song could rise quickly, dominate for weeks, and disappear just as fast—a constant turnover that, for teenagers, matched the intensity of their lives. Music became something to collect, share, and argue over. Owning a record was not only about sound; it was about belonging to a moment.

Record companies and advertisers moved quickly to shape this desire. Performers were styled carefully. Lyrics were scrutinized. Public appearances were designed to appeal to youthful fantasies without alarming parents too deeply. Artists such as Chuck Berry wrote songs that captured teenage routines with rare precision. They turned school, cars, and romance into vivid storytelling. Others, like Brenda Lee, were marketed as relatable figures. They balanced innocence and emotional depth.

Charts became another powerful tool. Rankings suggested objectivity. However, they also guided attention. A song’s position could influence radio play, retail placement, and public perception. Success often fed on itself. The higher a record climbed, the more visible it became. That pattern held regardless of whether its popularity reflected long-term impact or short-term excitement. This system rewarded immediacy and clarity. It sometimes did so at the expense of complexity.

Consumption extended beyond records. Music shaped fashion, dance styles, slang, and social behavior. A hit song could inspire hairstyles, clothing choices, and even moral debates. Parents worried that music encouraged rebellion. Teenagers often embraced that very tension. The industry learned to sell not just songs, but identities. Listening became an act of self-definition.

Access was not equal. Economic and racial inequalities meant that not every teenager could participate in the same way. Some experienced music primarily through radio. Others did so through live performance. Some only did so at the margins. Still, the idea of youth as a unified market took hold. In treating teenagers as a collective audience, the music business helped create the very group it sought to profit from. The consequences of that decision would shape popular culture for decades to come.

Rock and Roll: The Sound That Changed Everything

Rock and roll did not announce itself politely. When it began to spread in the early 1950s, it felt disruptive, noisy, and difficult to place. To some listeners it sounded raw and thrilling. To others it seemed unruly and threatening. What made it powerful was not only its sound. It was the way it unsettled existing boundaries between age groups, social classes, and racial identities. Rock and roll carried echoes of blues, gospel, rhythm and blues, and country. It refused to stay neatly within any one tradition.

For young audiences, this music felt immediate and personal. Its rhythms invited movement. Its lyrics spoke plainly. Its performers often appeared closer to ordinary life than polished stars of earlier popular music. For many adults, however, rock and roll seemed to challenge ideas of respectability, discipline, and control. Debates about morality, sexuality, and race followed quickly. They turned songs into symbols of broader social change.

The next chapters trace how rock and roll emerged, spread, and provoked reaction. They look closely at the musical roots that shaped the style, the artists who brought it into public view, and the environments in which rock and roll was performed and heard. Just as importantly, they consider why this music mattered so deeply to those who embraced it and why it alarmed those who did not.

Where Rock and Roll Really Came From

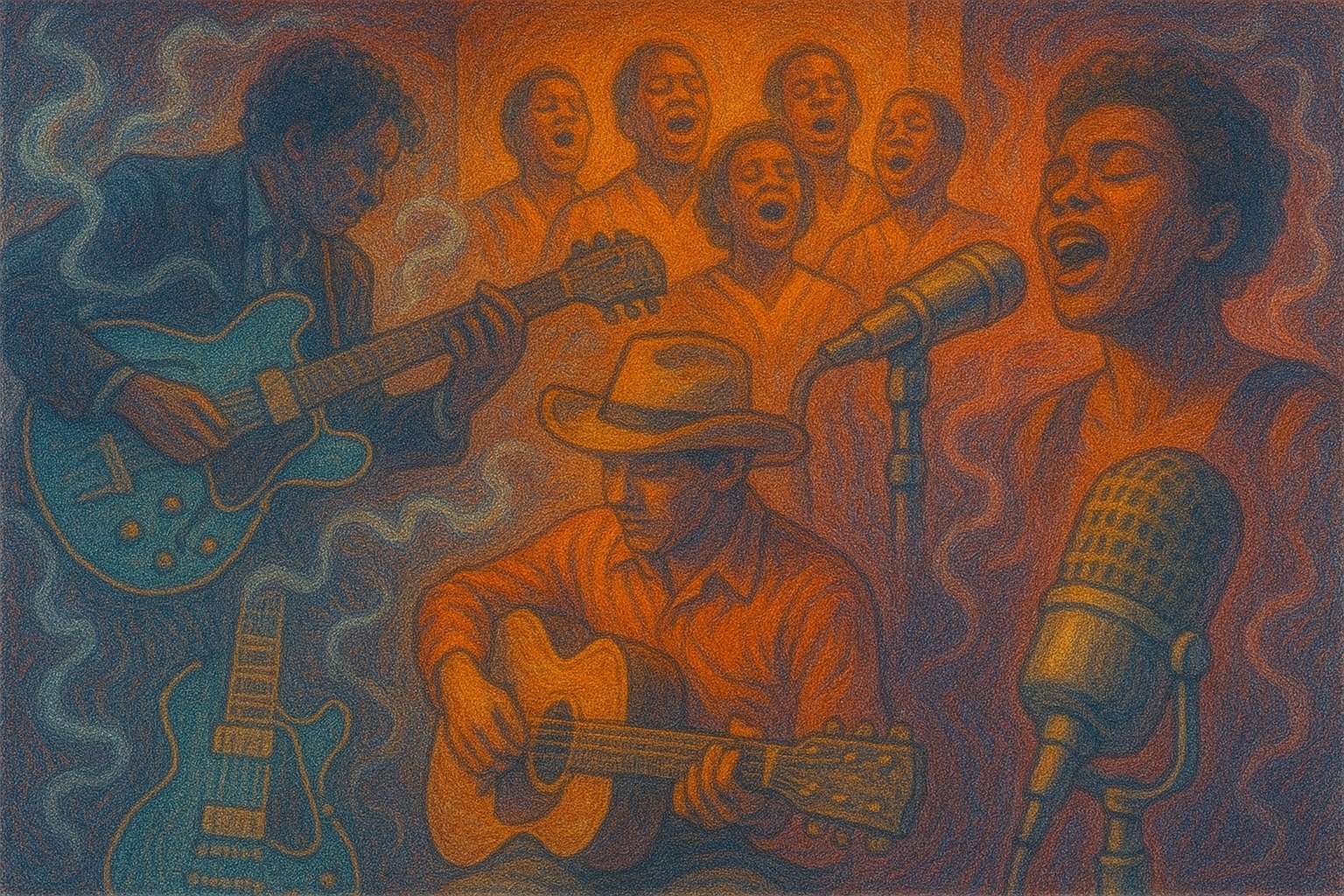

Rock and roll did not emerge from a single place or moment. Its foundations were laid over decades. They were shaped by musical traditions. These traditions developed largely within Black communities in the American South and urban centers. Blues, gospel, and rhythm and blues each contributed essential elements. These contributions were not only in sound. They were in attitude and emotional expression. What later audiences recognized as something new was, in many ways, a reconfiguration of familiar languages.

The blues provided the core vocabulary. Electric blues, in particular, emphasized amplified guitars, driving rhythms, and direct storytelling. Artists such as Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf recorded songs in the early 1950s that pushed volume and intensity forward. Their work reflected urban life and the Great Migration from the rural South to northern cities, capturing tension, humor, frustration, and desire with a clarity that resonated far beyond their original audiences.

Gospel contributed something different but equally important. Its call-and-response structures, emotional crescendos, and emphasis on vocal power shaped the way singers approached performance. When artists such as Ray Charles began blending gospel phrasing with secular themes, the result was controversial. However, it was transformative. The intensity of religious music was redirected toward love, pleasure, and personal freedom. This blurred lines that many listeners had assumed were fixed.

Rhythm and blues acted as the bridge between these traditions and a broader commercial audience. Often recorded for independent labels and marketed within segregated systems, rhythm and blues records emphasized strong backbeats, danceable grooves, and concise song structures. Artists like Ruth Brown and Big Joe Turner achieved significant success in the early part of the decade, demonstrating that this music could thrive commercially. Songs such as Shake, Rattle and Roll, which reached number one on the R&B chart in 1954, showed how humor, rhythm, and vocal force could combine into something immediately engaging.

Country music also played a role, particularly in its storytelling traditions and rhythmic simplicity. In regions where blues and country communities overlapped, musicians borrowed freely from one another. This happened sometimes unconsciously. The result was a shared musical space in which boundaries mattered less than feel.

These roots mattered because they grounded rock and roll in lived experience. The music spoke plainly. It often spoke about everyday situations. It favored energy over refinement. When rock and roll finally broke into the mainstream, it carried with it the weight of these traditions. This remained true even when their origins were obscured or simplified. Understanding these roots is essential to understanding why the music felt so alive. It also explains why it carried such cultural force when it finally reached a wider audience.

Elvis, Chuck Berry, and the Stars Who Made History

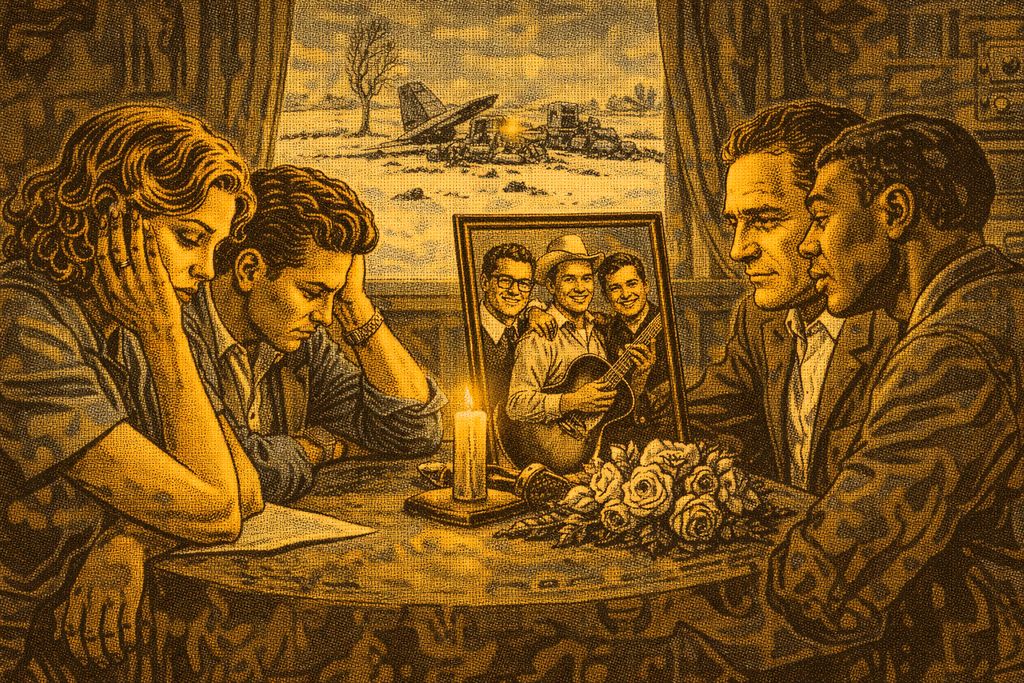

As rock and roll moved from regional scenes into the national spotlight, a small group of performers became its public face. They did not all come from the same background. They did not represent the music in the same way. What united them was timing, visibility, and a willingness—sometimes deliberate, sometimes accidental—to stand at the center of a cultural shift that was already underway.

One of the earliest figures to bring rock and roll into mainstream awareness was Elvis Presley. His recordings for Sun Records in the mid-1950s blended blues, country, and gospel influences. This created a style that felt both familiar and unsettling. Songs like That’s All Right and later hits such as Heartbreak Hotel introduced vocal intimacy and rhythmic looseness. These contrasted sharply with established pop conventions. Heartbreak Hotel was recorded in January 1956. It reached number one on Billboard’s pop chart by April of that year. It spent seven weeks at the top. As Presley himself later recalled of those early sessions, “We just played until it felt right. There was no plan, just music coming from somewhere inside.” Presley’s success was not only musical; his appearance, movement, and emotional delivery made him a focal point for debates about youth, sexuality, and respectability.

At the same time, Chuck Berry was defining another crucial aspect of rock and roll. His songwriting brought narrative clarity and wit to the genre. Tracks like Maybellene, released in July 1955, reached number five on the R&B chart and crossed into the pop top ten, while Roll Over Beethoven captured teenage life with specificity. They placed cars, school, and romance at the center of the story. Berry’s guitar playing was built around sharp rhythms and memorable riffs. It became a blueprint for generations of rock musicians. His records demonstrated something important. Rock and roll could be clever, structured, and grounded in everyday experience. During a legendary session for Chess Records, Berry reportedly improvised the opening guitar riff of Maybellene while producer Leonard Chess urged him to “keep it simple and make it jump.”

Other artists contributed different dimensions. Little Richard brought theatricality and explosive energy to the form. Songs such as Tutti Frutti, which climbed to number seventeen on the pop chart in 1956, and Long Tall Sally pushed vocal expression to extremes. They combined humor, intensity, and a sense of joyful excess. His performances challenged conventional ideas of gender and decorum, even as they drew heavily on gospel traditions.

Female artists were also present, though they often faced tighter constraints. Wanda Jackson emerged as a powerful voice in rockabilly. She delivered songs like Let’s Have a Party with confidence and drive. Her success showed something important: women could inhabit the sound and attitude of rock and roll, even as the industry offered them fewer opportunities and less promotional support.

These early stars did not invent rock and roll on their own. However, their records made it visible and unavoidable. Through radio play, touring, and television appearances, their songs traveled far beyond local scenes. In doing so, they transformed a set of musical practices into a shared cultural reference point. This point would soon reshape popular music across genres and generations.

Live Energy vs. Studio Polish: A Constant Tension

The tension between live performance and studio recording was central to the identity of early rock and roll. On stage, the music often felt volatile and unpredictable. In clubs, dance halls, and makeshift venues, performers fed directly off the energy of their audiences. Volume, movement, and spontaneity mattered as much as technical precision. These spaces allowed musicians to stretch songs, alter tempos, and respond to the mood of the room. They did so in ways that recordings rarely captured.

Touring circuits played a major role in shaping this live culture. Rock and roll shows were frequently packaged as traveling revues. They brought multiple artists together for long nights of performance. For many young listeners, these concerts offered a first experience of music as something physical and communal rather than distant. Dancing, shouting, and collective excitement were part of the event. At the same time, touring exposed deep inequalities. Black performers faced segregated accommodations, unsafe travel conditions, and limited access to venues. The road could be exhilarating, but it was also exhausting and precarious.

The studio presented a different set of pressures. Recording sessions demanded discipline and restraint. Time was expensive. Mistakes were costly. Producers often held final authority. Early rock and roll recordings were usually made quickly. They were sometimes made in a single take. However, they were still shaped by technical limits. Microphones favored certain vocal styles. Mono recording required careful balance between instruments. Producers such as Sam Phillips believed in capturing immediacy while maintaining control. This balance defined the sound of many influential records.

This contrast created a subtle conflict. Live performances emphasized freedom and excess. Studios rewarded clarity and repeatability. Some artists thrived in both environments. They translated stage energy into concise recordings. Others felt constrained by the studio. They sensed that something essential was being smoothed out. Audiences, meanwhile, encountered two versions of the same music. A song heard on the radio might feel restrained compared to its live counterpart. However, it was that polished version that traveled farthest.

Media exposure intensified this divide. Television appearances required even stricter control. They limited movement. They sometimes censored gestures deemed inappropriate. Performers were asked to contain the very qualities that made them exciting in live settings. This often frustrated artists. It heightened the sense that rock and roll was being domesticated for mainstream consumption.

The push and pull between rebellion and control shaped the genre’s early evolution. It influenced how songs were written. It influenced how artists were presented. It influenced how audiences understood authenticity. Rock and roll’s power came not from choosing one side over the other. It came from constantly negotiating the space between them.

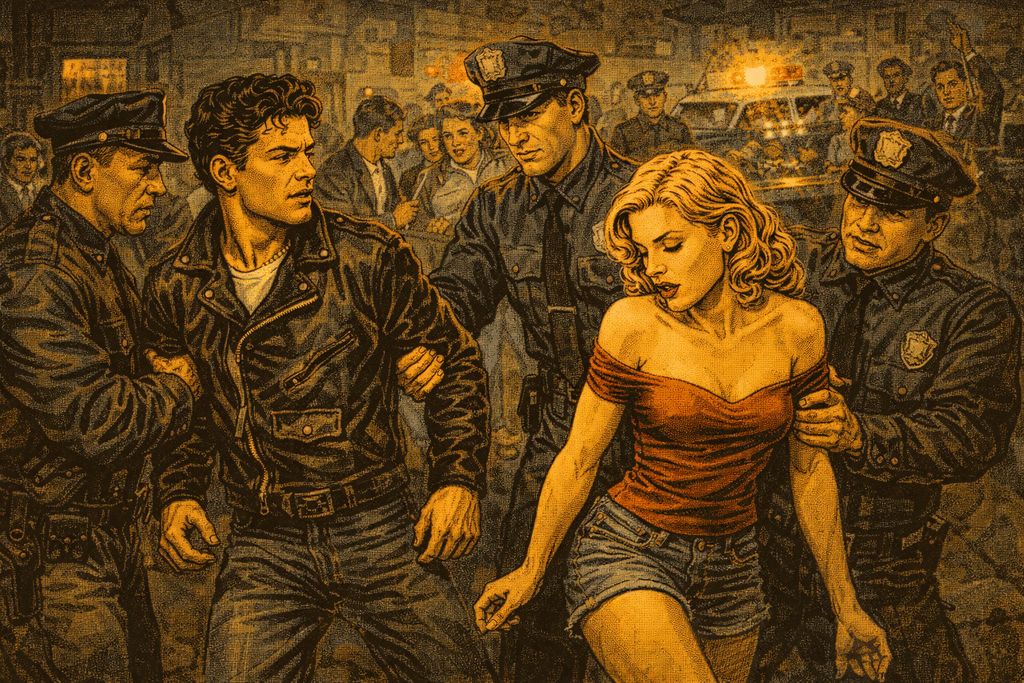

Why Parents Feared Rock and Teens Embraced It

As rock and roll gained visibility, it also attracted resistance. By the mid-1950s, public concern about the music had grown into something closer to moral panic. Critics rarely focused on musical structure or lyrical detail alone. Instead, they responded to what rock and roll seemed to represent. Movement, volume, sexuality, and racial mixing became symbols. They represented a broader fear. This fear was that traditional social order was slipping out of reach. As one prominent radio executive warned in 1955, “This music doesn’t just make teenagers dance. It makes them think and feel things we can’t control.”

Newspapers, parent organizations, and religious leaders often framed rock and roll as a threat to discipline and decency. Headlines warned of delinquency. Editorials linked music to juvenile crime and moral decline. Performers were scrutinized closely. The way an artist moved, dressed, or addressed an audience could provoke outrage. In this climate, the music itself was frequently secondary to the image surrounding it.

Television amplified these tensions. When Elvis Presley appeared on national broadcasts, camera angles were adjusted. They limited his movements. This reflected anxiety about how his performances might influence young viewers. Radio stations were under pressure from sponsors and local authorities. They sometimes removed songs from playlists or restricted airtime. In extreme cases, records were publicly denounced or destroyed. These were acts of symbolic protest.

This backlash was deeply generational. Teenagers often embraced the criticism as confirmation that the music belonged to them. What parents feared, young listeners found exhilarating. Rock and roll offered a language. This language felt unfiltered and honest, even when its messages were simple. The very fact that adults disapproved strengthened its appeal. Music became a space where young people could assert independence without directly confronting authority.

Race played a crucial role in these reactions. Much of the anxiety surrounding rock and roll was rooted in its Black origins. Its ability to cross racial boundaries also caused concern. Integrated concerts and shared musical tastes challenged long-standing norms. This happened even when those challenges went unspoken. Condemnation of the music often disguised discomfort with social change more broadly.

For artists, the backlash carried real consequences. Careers could stall under public pressure. Labels sometimes pushed performers toward safer material. However, the controversy also fueled visibility. Debate kept rock and roll in the public conversation. This ensured that it could not be ignored. Attempts to suppress the music often had the opposite effect. They drew attention to its energy and cultural relevance.

By the end of the decade, the panic had not disappeared. It had lost some of its force. Rock and roll had become too widespread to contain. The conflict between generations did not end. It reshaped the terms of popular culture. It established music as a central arena—and not only along generational lines.

Women Who Shaped the Sound of the Fifties

Gender, too, shaped who was heard and who was silenced. Women were not peripheral figures in the music of the 1950s but central voices who shaped how popular music sounded, felt, and was understood—often in the face of an industry that worked hard to limit their visibility or control their image. Female singers carried much of the decade’s emotional weight. Through ballads, jazz standards, rhythm and blues, and early rock and roll, they articulated longing, independence, humor, and vulnerability with a directness that resonated across audiences.

At the same time, their success existed within tight boundaries. Expectations around appearance, behavior, and repertoire were often more restrictive for women than for their male counterparts. Record labels and managers promoted carefully curated personas. Touring and media exposure came with additional scrutiny. Ambition and authority were frequently framed as problems to be managed. They were not seen as qualities to be celebrated.

Women stand at the center of the 1950s musical story—not as exceptions or novelties, but as artists navigating complex systems of power. The following discussion examines how female performers shaped pop, jazz, rhythm and blues, and rock and roll, how their voices helped define the decade’s sound, the structural limits they faced, and the quiet forms of resistance embedded in their music, performance, and career choices.

Peggy Lee, Ella Fitzgerald, and the Voices of Elegance

In the 1950s, pop and traditional vocal music offered women some of the most visible platforms in the industry. These styles valued clarity, emotional nuance, and interpretive skill. These qualities placed the voice itself at the center of attention. Female singers were expected to communicate feeling with precision. They often did so within carefully arranged orchestral settings. While this environment could feel restrictive, it also allowed many artists to develop strong musical identities that went far beyond surface polish.

One of the defining figures of the era was Peggy Lee. Her work in the early 1950s, particularly the album Black Coffee, released in 1956, introduced a restrained, intimate approach that contrasted with the more theatrical vocal styles of previous decades. Lee’s singing relied on subtle phrasing and understatement. Rather than projecting emotion outward, she invited listeners inward. She turned loneliness and desire into quiet conversations. This helped redefine what emotional depth in pop music could sound like.

Similarly influential was Ella Fitzgerald. Her career during the decade demonstrated a different form of authority. She was known for her technical mastery and improvisational skill. Fitzgerald bridged swing-era traditions and the emerging LP format. She did this through her Songbook recordings. Albums such as Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Cole Porter Songbook, released in 1956, treated popular songwriting as serious artistic material. Her work affirmed something important. Precision, joy, and intellectual engagement could coexist within mainstream vocal music.

Another crucial presence was Billie Holiday. Her influence continued to shape the decade even as her health and circumstances declined. Holiday’s interpretations carried emotional weight rooted in lived experience. She often bent melody and rhythm to serve meaning rather than technical perfection. Her recordings from the early 1950s retained a raw intimacy. This stood apart from the cleaner sound favored by many labels. This reminded listeners that vulnerability itself could be a form of strength.

The industry’s expectations for female pop singers were often contradictory. Women were encouraged to appear elegant and emotionally expressive, but rarely confrontational. Lyrics explored love, heartbreak, and longing. However, direct expressions of anger or independence were frequently softened. Despite this, many singers found ways to assert agency through song selection, phrasing, and collaboration with arrangers who respected their musical instincts.

Traditional vocal pop in the 1950s provided women with both opportunity and constraint. It offered national visibility and artistic legitimacy. At the same time, it reinforced narrow definitions of femininity. The enduring success of these artists lies in how they worked within those limits without being defined by them. Their recordings continue to resonate not because they conformed. They resonate because they infused familiar forms with personal truth.

Bold Women of Rock and R&B: Breaking Every Rule

While pop and jazz offered women a degree of visibility, rock and rhythm and blues presented a different kind of challenge. These styles were louder, more physical, and more closely associated with rebellion and sexuality. For women, entering this space meant confronting assumptions about who was allowed to sound forceful, playful, or openly assertive. The industry often treated female performers in these genres as anomalies—a pattern that persisted even when their influence was undeniable.

Rhythm and blues, in particular, relied heavily on female voices. LaVern Baker emerged as one of the most dynamic performers of the decade. She blended humor, strength, and emotional directness. Songs like Tweedlee Dee and Jim Dandy showcased her ability to command attention without softening her presence. Baker’s recordings were commercially successful and stylistically influential. However, her contributions were often framed as novelty rather than central achievement. In reality, her vocal power and rhythmic confidence helped define the sound of 1950s rhythm and blues.

Even more foundational was Big Mama Thornton, whose performances embodied a raw intensity that challenged gender norms outright. Her 1952 recording of Hound Dog reached number one on the R&B chart, combining humor, authority, and physical presence in ways that were rare for any artist, male or female. Thornton’s version pre-dated Elvis Presley’s famous 1956 cover by four years, carrying a sense of lived experience and command that later interpretations often lacked. Yet, despite the song’s massive influence, she received limited financial reward or recognition for her original recording—a stark example of the structural inequalities that shaped women’s careers in these genres.

Rock and roll, as it developed, inherited both the energy of rhythm and blues and the constraints placed upon female performers. Women were expected to temper their sound, balance toughness with approachability, and avoid appearing too confrontational. Some navigated this carefully, carving out space through stage presence and vocal delivery rather than overt defiance. Others found their careers curtailed by an industry uncertain how to market them.

Gospel-trained artists such as Sister Rosetta Tharpe further complicated these boundaries. Tharpe’s electrified guitar playing and joyful performance style blurred distinctions between sacred and secular music. Her influence on early rock musicians was profound. This was true even when her role was downplayed in later histories. She demonstrated something important. Virtuosity, faith, and showmanship could coexist. This expanded the possibilities for women in performance.

Women in rock and rhythm and blues did not merely participate in these genres; they shaped their sound, energy, and emotional range. Their struggles were not the result of limited talent or ambition but came from an industry slow to accept women who refused to stay within prescribed roles. Their recordings remain powerful reminders that the roots of rock and roll were never exclusively male, despite historical narratives that often suggest otherwise.

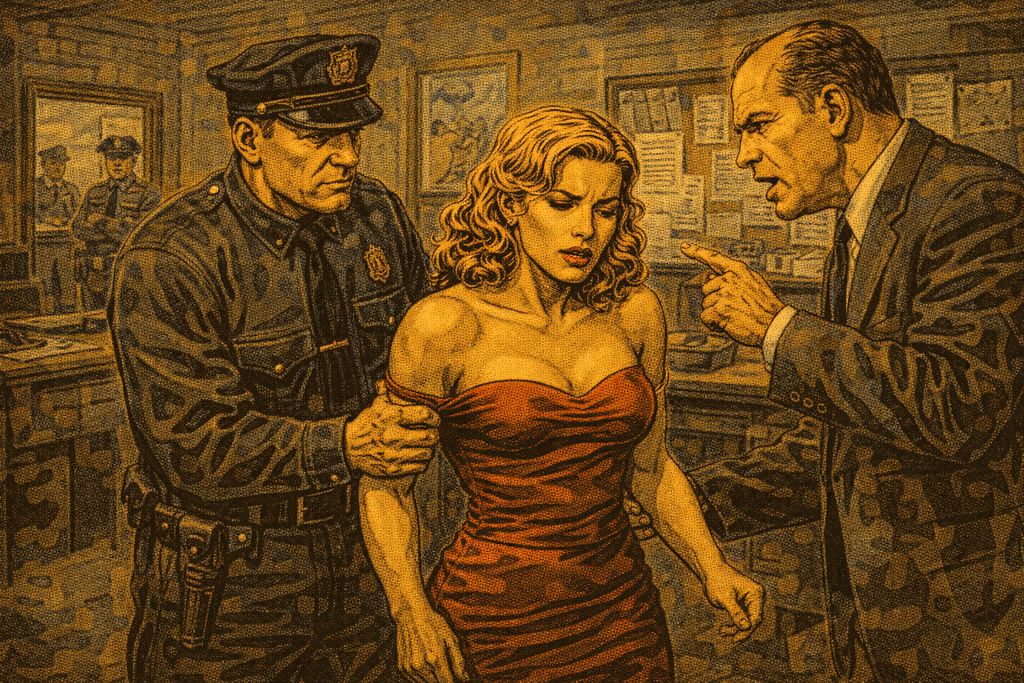

The Industry's Grip: How Women Were Controlled

Behind the visibility of female performers in the 1950s stood an industry that exercised careful and often intrusive control. Record labels, managers, and promoters shaped careers through contracts. These contracts limited artistic autonomy. They reinforced narrow ideas about how women should sound, look, and behave. Success was encouraged. However, it was encouraged only within clearly defined boundaries. Crossing them could result in lost promotion, reduced radio play, or quiet exclusion.

Image was a central concern. Female artists were expected to appear composed, attractive, and emotionally expressive. However, they were not to seem demanding or defiant. Publicity photographs, stage wardrobes, and interview narratives were tightly managed. A singer’s personal life was often framed as part of her appeal. Her musical decisions were treated as secondary. This focus placed additional pressure on women. They were expected to perform not only musically, but socially. Confidence could be misread as arrogance. Ambition could be misread as a lack of gratitude.

Contracts reflected these dynamics. Many women signed agreements that offered limited royalties. They offered little control over repertoire or recording schedules. Touring added further strain. Travel was exhausting. Safety was not guaranteed. Expectations of decorum followed performers everywhere. Unlike many male artists, women were often discouraged from appearing too visibly tired, angry, or independent. Emotional labor became part of the job—an unspoken requirement that rarely received recognition.

Despite these constraints, some artists found ways to assert agency. Peggy Lee negotiated greater creative input over arrangements and material. She quietly shaped the sound of her recordings. Others exercised control through song choice. They gravitated toward material that allowed subtle expressions of frustration, longing, or autonomy. In rhythm and blues, performers like Ruth Brown later challenged unfair contracts. This drew attention to systemic exploitation that affected many artists, especially women.

The emotional cost of these pressures was rarely acknowledged at the time. Discussions of mental health were almost nonexistent. Burnout was often interpreted as personal weakness rather than structural failure. When careers stalled, responsibility was frequently placed on the artist. It was not placed on the conditions surrounding her work. This silence has contributed to the underrepresentation of women’s struggles in historical accounts of the decade.

Gendered success in the 1950s was a careful balancing act. Women were celebrated for their voices, yet constrained in their choices. Their achievements were real—often accomplished despite the systems meant to support them. Recognizing these dynamics clarifies rather than diminishes their artistry, revealing the resilience and quiet resistance embedded in their work.

Jazz's Golden Age: When Music Became Art

While teenagers danced to rock and roll and women fought for recognition in pop and R&B, jazz was undergoing its own transformation. The genre entered the 1950s as a mature art form with a long, complex history—it had filled ballrooms, dominated radio, and produced some of the century’s most influential musicians. But the decade brought profound change. Big bands were fading. Audiences were fragmenting. Jazz was shifting from mass entertainment toward something more specialized: a listening-focused art.

This transition was not a decline. It was a reorientation. Smaller ensembles allowed for greater experimentation. New recording formats made extended improvisation possible on record. Jazz musicians began to explore mood, texture, and space in ways that challenged earlier conventions. The music took on new meanings. It became associated with intellectual seriousness, artistic independence, and, for many listeners, cultural sophistication.

Jazz in the 1950s also reflected broader social tensions. Issues of race, authorship, and recognition were impossible to ignore. Black musicians continued to innovate. However, they often received less financial security and public acknowledgment than their white counterparts. Clubs, festivals, and recording studios became sites where artistic ambition met economic and social constraint.

Jazz’s evolution comes into focus through the artists, albums, and spaces that defined its changing identity. The following pages show how jazz navigated shifting audiences, technological advances, and cultural expectations, ultimately laying groundwork that would influence both the avant-garde and the mainstream in the years to come.

From Swing to Bebop: Jazz's Dramatic Evolution

The shift from swing to bebop and later to cool jazz marked one of the most significant turning points in jazz history. Swing had dominated the 1930s and early 1940s. It was built around large ensembles, danceable rhythms, and tightly arranged charts. By the early 1950s, however, the economic and cultural conditions that sustained big bands had changed. Maintaining large groups was expensive. Audiences were splintering. Musicians were increasingly drawn to smaller settings. These settings allowed greater individual expression.

Bebop emerged from this environment. It was both a musical and cultural statement, developed earlier in the 1940s but reaching broader visibility in the following decade. It favored small combos, fast tempos, and complex harmonic structures. Improvisation became central rather than decorative. Artists such as Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie reshaped the language of jazz. They pushed it away from dance halls and toward attentive listening. Their recordings challenged audiences. They demanded focus and familiarity with musical form. Jazz was no longer primarily social music. It was increasingly presented as an art that required engagement.

This shift had social implications as well. Bebop was closely associated with Black urban culture and artistic autonomy. Its complexity resisted easy commercialization. Some musicians saw this as a form of protection against exploitation. However, this resistance also limited its mainstream reach. Clubs replaced ballrooms. The audience often became smaller, more specialized, and more male. Jazz was gaining artistic prestige. It was losing mass visibility.

Cool jazz developed partly in response to these changes. It retained bebop’s emphasis on improvisation but softened its edges, favoring relaxed tempos, lighter textures, and a more restrained emotional tone. Miles Davis played a key role in this transition, particularly through recordings such as Birth of the Cool. These sessions, recorded between 1949 and 1950 and released in 1957, emphasized balance, space, and ensemble interplay, offering an alternative to bebop’s intensity. Cool jazz found receptive audiences on the West Coast and among listeners drawn to its reflective atmosphere.

The coexistence of bebop and cool jazz in the 1950s revealed the genre’s growing diversity. Jazz was no longer moving in a single direction. It was branching, adapting to different audiences and artistic priorities. Some listeners embraced its intellectual demands, while others were drawn to its quieter, more introspective moods.

This period of transition set the stage for future developments, from hard bop to modal and avant-garde jazz. Miles Davis’s 1959 album Kind of Blue, released in August 1959, became a landmark of modal jazz. Its emphasis on scale-based improvisation rather than chord progressions influenced countless musicians and expanded the possibilities of jazz expression. As Davis himself famously explained his approach to improvisation, “I’ll play it and tell you what it is later.” More importantly, the decade established a new understanding of jazz as a flexible, evolving art form, capable of reinvention without losing its core identity.

The Albums That Made Jazz History

The 1950s marked a turning point in how jazz was recorded, packaged, and understood. The long-playing album changed the relationship between musicians and listeners, allowing ideas to unfold over time rather than being compressed into short singles. This shift encouraged artists to think in broader arcs, treating albums as cohesive statements rather than collections of unrelated tracks. For jazz, a genre rooted in improvisation and nuance, this development was transformative.

One of the most influential figures of the decade was Thelonious Monk. His recordings from the mid-1950s, including Brilliant Corners, released in 1956, challenged conventional notions of harmony, rhythm, and form. Monk’s compositions were angular and unpredictable. They demanded close attention from both fellow musicians and listeners. Studio sessions were often difficult, not because of a lack of preparation, but because his music resisted easy execution. The resulting recordings captured tension and personality. They preserved the sense of risk that defined his approach.

Another milestone came from Miles Davis. His work throughout the decade reflected constant refinement. Albums such as ‘Round About Midnight, released in 1957, presented jazz as both modern and accessible. It balanced complex improvisation with a sense of mood and restraint. Davis’s ability to assemble distinctive ensembles and allow space within arrangements demonstrated how leadership and collaboration could coexist in recorded form.

The decade also elevated the role of the studio itself. Labels like Blue Note Records became known for their commitment to sound quality and artistic freedom. Producers encouraged extended takes, used careful microphone placement, and created relaxed session environments. This approach allowed musicians to perform with a degree of comfort that mirrored live settings while still benefiting from the clarity of recording technology.

Vocal jazz also flourished in album form. Singers used the LP to explore repertoire with greater depth. They often revisited standards with new interpretive angles. The album became a space for storytelling, emotional continuity, and artistic identity. Rather than chasing immediate hits, many jazz artists focused on building bodies of work that reflected their evolving voices.

These landmark albums and sessions did more than document performances. They shaped how jazz was heard, studied, and remembered. By capturing extended improvisation and subtle interaction, recordings from the 1950s preserved moments that might otherwise have been lost. They also helped define the album as a serious artistic medium, influencing not only jazz, but the future of popular music as a whole.

The Clubs: Where Jazz Really Lived

While recordings shaped jazz’s legacy in the 1950s, live performance remained the music’s lifeblood. Clubs were where ideas were tested, refined, and exchanged, often night after night. The jazz economy of the decade depended on these spaces, small rooms where musicians and audiences met at close range. The atmosphere was intimate, sometimes tense, and deeply social. Listening was active. Applause, silence, and conversation all fed back into the performance.

Urban migration played a decisive role in shaping this live culture. The movement of Black Americans from the rural South to northern and western cities transformed neighborhoods and musical scenes. Cities such as New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Detroit became hubs where musicians could find work, collaborators, and audiences. These environments encouraged stylistic exchange. Blues musicians encountered jazz players. Swing veterans played alongside younger bebop innovators, and boundaries softened through proximity.

Clubs like the Five Spot in New York or small West Coast venues offered platforms for experimentation. Performers were often paid modestly, sometimes relying on multiple sets per night to make a living. Touring schedules were demanding, and stability was rare. Yet these spaces allowed musicians to develop personal voices away from the constraints of radio and studio expectations. Extended solos, unusual arrangements, and spontaneous interactions were not only tolerated but encouraged.

The live jazz economy also reflected broader inequalities. Segregation affected where musicians could perform and who could attend. Integrated audiences were more common in northern cities, but discrimination remained present in hiring practices and pay. Many Black musicians found that their music attracted white audiences while their personal freedom remained restricted. This contradiction was part of daily life on the bandstand.

Despite these challenges, live performance fostered community. Musicians learned from one another through shared stages and informal mentorship. Younger players absorbed techniques and attitudes simply by listening and participating. The club circuit functioned as an education system, passing down knowledge that could not be fully captured on record.

By the end of the 1950s, economic pressures and changing tastes began to threaten some of these spaces. Rock and roll drew younger audiences away, and rising costs made it harder to sustain small venues. Still, the live jazz economy of the decade left a lasting imprint. It shaped the sound, discipline, and resilience of musicians whose influence would extend far beyond the rooms in which they played.

Who Owned Jazz? The Fight for Recognition

By the 1950s, jazz occupied an uneasy position within American culture. It was increasingly described as serious art, discussed in critical language, and presented in concert halls rather than only in clubs or ballrooms. At the same time, the question of who held cultural authority over jazz remained deeply contested. The music’s roots were unmistakably Black, yet its growing institutional recognition often benefited white musicians, critics, and promoters more visibly.

For many Black artists, jazz represented autonomy and intellectual freedom. Musicians such as Charles Mingus used composition and performance to assert control over their work and to comment, sometimes explicitly, on racial injustice. Mingus’s music carried emotional intensity and structural ambition, refusing to separate artistry from lived experience. His approach challenged the idea that jazz should be detached or purely decorative.

At the same time, white musicians increasingly entered the jazz mainstream, often receiving broader critical acceptance and commercial opportunity. This was not simply a matter of talent, but of access. Integrated bands were more common than in earlier decades, yet the industry continued to privilege whiteness in marketing and media representation. Jazz magazines, college lectures, and festival programming sometimes framed the music as universal while overlooking the social conditions that shaped it.

Cultural authority also played out through language. Jazz was described as sophisticated, modern, or cerebral, terms that carried social weight. These labels helped elevate the genre’s status, but they could also strip it of context. When jazz was presented as abstract art, divorced from the realities of segregation and discrimination, the experiences of its creators risked being softened or erased.

International recognition added another layer. European audiences often embraced jazz as an expression of freedom and individuality, sometimes granting Black American musicians respect they struggled to find at home. Tours abroad offered artistic validation, yet they also highlighted the contradictions of returning to a society that continued to limit opportunity based on race.

Despite these tensions, the elevation of jazz in the 1950s mattered. It expanded the space where musicians could work and be heard, encouraging deeper listening and long-term engagement. But it also revealed how cultural authority is negotiated, not given. Jazz’s journey shows how art can gain prestige while its creators continue fighting for recognition and control—struggles rooted in traditions that long predated the decade.

The Roots: Blues, Country, and Gospel

Those traditions deserve attention on their own terms. Jazz, rock and roll, and R&B didn’t emerge from nowhere. Beneath the decade’s innovations lay older traditions with deep regional roots—blues, country, and gospel. These genres had long histories tied to place, work, faith, and community. What changed in the 1950s was how they moved: migration, recording technology, and independent labels pulled regional sounds into national circulation without erasing their local character.

These genres formed the backbone of American popular music, even when they were not always credited as such. Blues adapted to urban life through amplification and new rhythmic emphasis. Country music shifted from rural storytelling to a more commercial, studio-centered sound. Gospel continued to shape vocal technique and emotional intensity, quietly influencing secular styles that would soon dominate the charts.

The focus here is on foundations rather than breakthroughs. It looks at how regional scenes, small studios, and independent labels created environments where musicians could experiment, survive, and sometimes thrive. It also addresses the inequalities embedded in these systems, where creative influence did not always translate into financial security or historical recognition. By examining these roots closely, it becomes easier to understand why the music of the 1950s felt both grounded and restless, anchored in tradition while constantly pushing toward something new.

Chicago Blues: How the Electric Sound Was Born

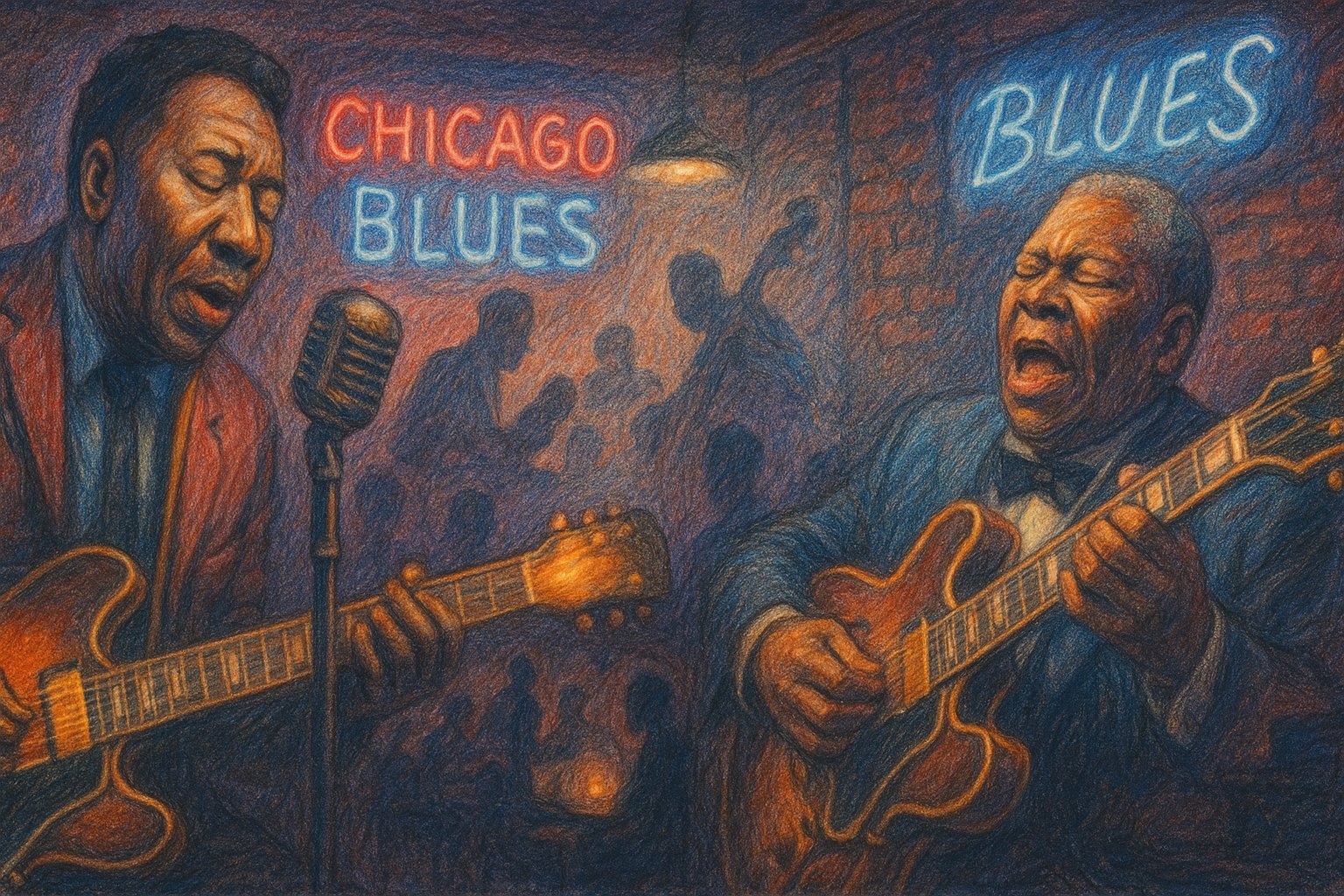

The electric blues of the 1950s was shaped as much by geography as by sound. As Black Americans migrated from the rural South to northern cities in search of work and relative safety, they carried musical traditions with them. In urban environments, those traditions changed. Acoustic instruments gave way to amplified guitars, harmonicas, and drums that could cut through the noise of crowded clubs and packed dance floors. The result was a blues that felt harder, louder, and more insistent, mirroring the realities of city life.

Chicago became the most influential center of this transformation. Independent labels recognized both the artistic and commercial potential of the new sound, recording musicians who had honed their craft in the Mississippi Delta and beyond. Muddy Waters was among the most significant figures of this shift. His recordings for Chess Records in the early 1950s, including songs like Hoochie Coochie Man and I’m Ready, defined the structure and attitude of electric blues. Waters combined traditional lyrical themes with amplified instrumentation and a commanding vocal presence, creating music that felt rooted yet unmistakably modern.

Another key voice was Howlin’ Wolf, whose raw, gravelly delivery set him apart from nearly every contemporary. His recordings carried a sense of physical force and emotional urgency that resisted polish. Songs such as Smokestack Lightning blurred the line between rhythm and blues and emerging rock and roll, influencing musicians well beyond the blues scene. Wolf’s work demonstrated that intensity itself could be a defining aesthetic.

Electric blues was not only about individual stars. It reflected a collective experience shaped by labor, displacement, and adaptation. Urban blues lyrics often spoke of crowded streets, unstable relationships, and hard-won confidence. The music favored repetition and groove, allowing listeners to settle into its rhythms while absorbing its emotional weight. These qualities made it especially suited to live performance, where volume and presence mattered as much as subtlety.

Despite its influence, electric blues remained constrained by the structures of the industry. Records were often marketed within segregated categories, limiting radio exposure and crossover success. Financial rewards were modest. Many musicians balanced recording with factory work or touring under difficult conditions. However, the reach of the music extended far beyond its immediate audience. White rock musicians listened closely. They absorbed phrasing, riffs, and attitude that would later reappear in altered form.

The electric blues of the urban North laid essential groundwork for what followed. It provided a sonic bridge between rural tradition and modern popular music, preserving emotional directness while embracing new technology. Its legacy is not only audible in later rock and soul, but in the enduring idea that music can adapt to new environments without losing its core truth.

Country Music: Stories From the Heart

Country music in the 1950s was undergoing its own quiet transformation. Often framed as conservative or static, the genre was in fact responding actively to the same social and economic shifts reshaping the rest of American culture. Migration, commercialization, and the growth of the recording industry altered how country music was written, recorded, and heard. While its themes remained closely tied to everyday life, the sound itself was becoming more polished and more widely distributed.

The rise of Nashville as an industry center was central to this change. Recording studios, publishers, and radio stations clustered around a system that prioritized consistency and marketability. This environment favored clear storytelling, steady rhythms, and arrangements that could appeal beyond regional audiences. Artists such as Hank Williams had already demonstrated the emotional power of simplicity before his death in 1953. Songs like Your Cheatin’ Heart and I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry continued to shape the genre throughout the decade, setting a standard for lyrical honesty and melodic restraint.

Honky-tonk remained a vital current within country music, emphasizing themes of heartbreak, alcohol, and working-class struggle. Performers delivered songs with a plainspoken directness that resonated with listeners navigating economic uncertainty and personal loss. Lefty Frizzell emerged as a defining voice of this style, influencing vocal phrasing and song structure across the genre. His relaxed, behind-the-beat delivery brought a sense of intimacy that distinguished him from earlier performers.

At the same time, country music was increasingly intersecting with mainstream pop. String sections, backing vocals, and smoother production began to appear more frequently, especially in recordings aimed at national radio play. This crossover potential expanded audiences but also sparked debate within the genre. Some listeners welcomed the broader reach, while others feared a loss of authenticity. The tension between tradition and commercial adaptation became a recurring theme.

Country music’s relationship with race was complex. While the genre was marketed primarily to white audiences, it shared deep roots with blues and gospel traditions developed by Black musicians. These connections were rarely acknowledged openly, yet they shaped rhythmic feel, vocal inflection, and song themes. The separation of genres often reflected social boundaries rather than musical ones.

By the end of the 1950s, country music had secured a stable place within the national media landscape. It may not have generated the same level of controversy as rock and roll, but its influence was profound. Through its evolving sound and expanding reach, country music helped define ideas of sincerity, regional identity, and emotional storytelling that would continue to shape American popular music in the decades that followed.

Gospel: The Soul Behind the Music

Gospel music remained one of the most powerful and influential forces in the 1950s, even when it was not always visible within the mainstream industry. Rooted in church traditions, gospel emphasized collective expression, emotional release, and spiritual conviction. Its impact extended far beyond religious settings, shaping vocal techniques, rhythmic structures, and performance styles that would become central to popular music across genres.

Churches functioned as both spiritual and musical training grounds. Choirs, soloists, and musicians learned discipline, projection, and the ability to move an audience emotionally. Call-and-response patterns encouraged participation rather than passive listening, reinforcing the idea that music was something shared. This communal energy distinguished gospel from many secular forms and gave performers a deep sense of presence and confidence. For many artists, the church was where their musical identity first took shape.

The boundary between sacred and secular music was often contested. Crossing it could provoke controversy, particularly when gospel-trained singers brought religious intensity into popular music. Ray Charles became one of the most prominent figures associated with this shift. By applying gospel phrasing and structure to songs about love and desire, he challenged assumptions about where spiritual expression belonged. As Charles later explained his approach to music, “I don’t divide music into categories like sacred and secular. Music is music. If it feels right and moves people, then that’s what matters.” His work in the mid-1950s was both celebrated and criticized, revealing deep tensions around faith, morality, and artistic freedom.

Other performers navigated this divide more cautiously. Some maintained parallel careers, performing gospel in church settings while recording secular material under different expectations. This dual existence reflected broader social realities. Gospel offered moral grounding and community support, while secular music provided broader exposure and financial opportunity. The decision to move between these worlds was rarely simple and often carried personal cost.

Gospel’s influence was especially audible in vocal delivery. Techniques such as melisma, dynamic shifts, and emotional emphasis became hallmarks of rhythm and blues and early rock and roll. Even when lyrics moved away from religious themes, the intensity of expression remained. Audiences responded to this authenticity, often without recognizing its origins.

Despite its importance, gospel music itself received limited institutional support. Recordings were often made with modest resources. Artists rarely achieved the same commercial recognition as their secular counterparts. However, the genre’s legacy was profound. Gospel provided the emotional engine behind much of the decade’s most influential music. It infused popular forms with urgency, hope, and resilience.

Understanding gospel’s role in the 1950s reveals how deeply interconnected sacred and secular traditions were. Rather than existing in isolation, they formed a continuous exchange, one that shaped not only sound, but values, performance, and the emotional language of modern popular music.

Small Studios, Big Revolution: Sun, Chess, and Atlantic

Much of the most influential music of the 1950s did not originate in major corporate offices or carefully planned marketing campaigns. It emerged from small studios, independent labels, and regional networks that operated close to the musicians themselves. These spaces were often modest, sometimes improvised, but they allowed for experimentation that larger companies were unwilling or unable to support. In doing so, they played a decisive role in shaping the sound of the decade.

Regional studios were deeply connected to place. They reflected local accents, musical traditions, and social realities. In Memphis, Sun Records became known for recordings that blended blues, country, and gospel influences with minimal polish. Under the guidance of Sam Phillips, the studio prioritized emotional immediacy over technical perfection. This approach allowed performers to sound unguarded and present, qualities that resonated strongly with emerging rock and roll audiences.

In Chicago, Chess Records documented the evolution of electric blues with a focus on power and clarity. The label’s recordings captured the intensity of urban performance, preserving a sound that might otherwise have remained local. Atlantic Records, operating between regional scenes and national markets, played a similar role for rhythm and blues, helping artists reach broader audiences while maintaining stylistic identity.

These independent labels often worked with limited resources. Recording sessions were short. Promotion budgets were small. Financial risk was constant. Still, this scarcity encouraged flexibility. Musicians were given room to try ideas that might not have fit established formats. Producers listened closely. They adapted to the strengths of individual performers rather than forcing them into predefined molds. The result was a diversity of sounds that larger labels struggled to replicate.

Local radio stations, record stores, and live venues formed essential support systems. DJs acted as cultural intermediaries, championing regional hits and introducing new artists to curious listeners. Word of mouth played a significant role, allowing music to spread organically before it reached national charts. This grassroots circulation often preceded mainstream recognition, demonstrating how influence could build quietly before becoming visible.

The importance of regional studios lies not only in the artists they launched, but in the values they upheld. They treated music as something rooted in community rather than abstraction. By staying close to everyday experience, these labels preserved authenticity at a time when commercialization was accelerating. Their legacy is woven throughout the music of the 1950s, reminding us that innovation often begins at the margins before it reshapes the center.

Pop Perfection: How Hits Were Made

As regional roots moved into wider circulation, another system of popular music quietly defined how songs were written, recorded, and remembered. Pop in the 1950s was not only a genre, but an architecture. It relied on carefully crafted melodies, vocal harmony, orchestral arrangements, and an emerging understanding of how records could shape mood over time. This music spoke to adult listeners, late-night intimacy, and emotional reflection, offering a counterbalance to the urgency of youth culture.

Crooners, vocal groups, arrangers, and songwriters played central roles in this ecosystem. Their work emphasized songcraft, control, and narrative continuity. The long-playing album became a canvas for sustained emotional storytelling, while harmony groups brought collective voices into the foreground, often reflecting urban life and shared experience. These forms of pop did not reject change. They absorbed it, adapting to new technologies and audiences while maintaining a sense of polish and restraint.

This segment explores how pop music was constructed in the 1950s, focusing on the voices and structures that supported it. It examines how harmony, arrangement, and songwriting shaped listening habits and industry practices, and how these systems influenced artists across genres. In doing so, it shows that the decade’s musical revolution was not only about disruption, but also about design, continuity, and the careful shaping of sound into lasting form.

Doo-Wop: When Street Corners Became Stages

Doo-wop and vocal group music formed one of the most distinctive and emotionally resonant sounds of the 1950s. This style emerged largely from urban neighborhoods. It grew out of informal settings rather than formal institutions. Street corners, schoolyards, and apartment hallways served as rehearsal spaces. Young singers experimented with harmony, rhythm, and call-and-response patterns. These environments shaped a music that felt communal, immediate, and deeply connected to everyday life.

Vocal groups emphasized blend over virtuosity. Individual voices mattered, but unity was the goal. Simple chord progressions and repeated syllables created space for expressive leads. These songs often sang about love, longing, and uncertainty. Groups like The Platters brought this sound into the mainstream with songs such as Only You and The Great Pretender. Their polished delivery and romantic themes appealed to both teenage and adult audiences. This demonstrated that harmony-based music could cross generational lines.

At the same time, other groups maintained a closer connection to their street-level origins. The Drifters blended gospel influence with rhythm and blues. Their recordings felt grounded and emotionally direct. Songs like There Goes My Baby introduced orchestral textures while retaining the group’s expressive core. This reflected how vocal music adapted to changing production styles without losing its identity.

Youth played a central role in this movement. Many performers were teenagers themselves, singing about experiences they were actively living. Frankie Lymon and The Teenagers embodied this immediacy with Why Do Fools Fall in Love, a song whose vulnerability and enthusiasm resonated widely. The success of such records revealed a growing appetite for authenticity, even within carefully produced contexts.

Despite their popularity, vocal groups often faced harsh industry realities. Contracts were restrictive. Royalties were minimal. Group members were frequently treated as interchangeable. Creative control was limited. Long-term stability was rare. The music endured because it fulfilled a social need. It allowed listeners to hear themselves reflected in harmony. They could experience collective emotion in a rapidly changing world.

Doo-wop and vocal group music provided an essential bridge between community expression and commercial pop. Its influence can be heard in later soul and R&B. It also lives on in an enduring idea: voices joined together can express feelings that no single voice can fully carry alone.

Sinatra and the Crooners: Voices of Intimacy

Crooners occupied a central place in the musical life of the 1950s. They offered a form of pop that was intimate, controlled, and carefully shaped for adult listeners. Their appeal did not rest on volume or spectacle. It rested on phrasing, tone, and emotional nuance. These singers addressed listeners directly, often as if in conversation. This created a sense of closeness that suited late-night listening and private reflection.

The long-playing album was crucial to this approach. Unlike singles-driven youth markets, adult pop favored sustained mood over immediate impact. Frank Sinatra was the most influential figure in defining this form. Albums such as In the Wee Small Hours, released in 1955, presented heartbreak and loneliness not as isolated moments. They presented them as emotional landscapes that unfolded track by track. Sinatra’s control over phrasing and timing, combined with thoughtful sequencing, helped establish the album as a cohesive artistic statement. It was not just a loose collection of songs.

Orchestral arrangements played an equally important role. Arrangers shaped the emotional framework within which crooners worked. They used strings, brass, and subtle rhythmic shifts to support the vocal line rather than overwhelm it. Nat King Cole exemplified this balance. His recordings paired warmth and elegance with restraint. This allowed his voice to remain central even within lush arrangements. Albums such as Love Is the Thing, released in 1957, demonstrated how orchestration could deepen emotional impact without sacrificing clarity.

Female crooners also defined the era’s sound. Peggy Lee brought a quieter, more introspective sensibility to adult pop. Her understated delivery challenged the assumption that emotional power required volume. Instead, Lee used space and subtlety, inviting listeners to lean in. This approach expanded the expressive range of pop music, making room for vulnerability and ambiguity.

Crooners were closely tied to radio and film. These media reinforced their association with sophistication and stability. Their music often accompanied images of romance, urban nightlife, and refined leisure. For many listeners, this sound represented continuity in a decade marked by rapid change. It offered reassurance without stagnation. It offered modernity without rupture.

Adult pop in the 1950s did not compete directly with rock and roll. Instead, it coexisted. It served different emotional needs and life stages. Together, these parallel systems revealed how diverse the decade’s musical landscape truly was. The crooner tradition demonstrated that innovation could occur through refinement as much as rebellion. It shaped how popular music would be heard and understood long after the decade ended.

The Hidden Architects: Songwriters and Producers

Behind the voices and faces that defined 1950s popular music stood a network of songwriters, producers, and arrangers. Their influence was profound but often understated. These figures shaped how songs were structured. They shaped how recordings sounded. They shaped how artists were positioned within the industry. Performers received public recognition. However, much of the creative and economic power resided elsewhere. It was located in offices, studios, and publishing houses where decisions were made quietly and decisively.

Songwriting in the 1950s was becoming increasingly professionalized. Teams replaced lone composers. Songs were crafted with specific artists, markets, and formats in mind. One of the most influential partnerships of the decade was Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. Their work bridged rhythm and blues, pop, and early rock and roll. Their songs combined sharp observation with musical economy. They created narratives that felt vivid and contemporary. Tracks written for artists like The Coasters demonstrated how humor, character, and storytelling could coexist within commercial frameworks.

Producers played an equally critical role. They mediated between artistic impulse and technical reality. They shaped performances through arrangement, pacing, and sound balance. Mitch Miller was a powerful figure at Columbia Records. He exemplified a more directive approach. His influence extended beyond individual sessions into broader trends. He encouraged sing-along arrangements and tightly controlled production values. His methods were controversial. They reflected the industry’s growing desire for predictability and mass appeal.

Independent producers often operated differently. Figures like Ahmet Ertegun fostered environments where artists were encouraged to bring their own sensibilities into the studio. This flexibility allowed rhythm and blues performers to retain elements of live performance—a pattern that held even as recordings reached wider audiences. The contrast between these approaches highlights the diversity of production philosophies active during the decade.

Arrangers, too, left a lasting mark. Their decisions determined whether a song felt expansive or intimate. They determined whether it felt urgent or reflective. They were rarely credited publicly. Their work shaped emotional response. It guided listeners through dynamics and texture without drawing attention to itself.

These invisible architects did not simply support popular music. They structured it. By defining how songs were written, recorded, and presented, they influenced which voices were heard. They influenced how long they endured. Understanding their role reveals something important. The sound of the 1950s was not only performed. It was carefully built, one decision at a time.

Technology and Power: Who Controlled the Sound

As pop, jazz, blues, and rock moved through larger markets, the systems behind them became more decisive. The sound of 1950s music was shaped not only by artists and songs, but also by the mechanisms that recorded, distributed, and promoted them. Technology and industry power worked quietly in the background, but their influence was constant. Decisions about microphones, tape, studio time, contracts, and radio access affected what listeners ultimately heard. They affected how often listeners heard it. These forces did not determine creativity. They framed its possibilities.

The decade saw rapid changes in recording practices and media reach. Advances in tape technology improved sound quality and editing. Radio remained the dominant channel for exposure. At the same time, the growing concentration of power within record labels and broadcasting networks created new forms of control. Artists navigated an environment where opportunity and restriction were closely linked. Success could bring visibility. It could also bring loss of autonomy.

It examines how technology and industry structures shaped musical outcomes in the 1950s. It looks at recording techniques, ownership models, and the gatekeeping role of radio and charts. It also addresses the tensions that arose when commercial interests collided with artistic freedom. By understanding these systems, it becomes easier to see why certain sounds flourished, others struggled, and why debates about fairness and influence became impossible to ignore as the decade progressed.

Recording Tech: Limits That Became Style

Recording technology in the 1950s imposed clear limits. Those limits became part of the music’s character. Most commercial recordings were made in mono. Musicians performed together in the same room. Balance was achieved through placement rather than post-production. Singers leaned toward microphones. Drummers played with restraint. Guitar amplifiers were positioned carefully to avoid distortion. The result was a sound that felt immediate and human, shaped by physical presence rather than later correction.

Magnetic tape became standard during the decade. It introduced new flexibility. Compared to earlier disc-cutting methods, tape allowed longer takes, splicing, and modest editing. This change mattered deeply for jazz and rhythm and blues. Extended performances and subtle interaction were essential in these genres. Producers could capture a complete feel rather than assembling fragments. Editing remained minimal. Performers were expected to deliver convincing takes in real time. This reinforced discipline and preparation.

Studios themselves had personalities. Room size, wall materials, and equipment varied widely, especially outside major corporate facilities. At Sun Records, the studio’s natural echo became a defining feature. It added depth and urgency to recordings without artificial effects. In contrast, larger studios associated with labels like Columbia Records favored controlled acoustics and orchestral clarity, especially for pop and vocal music.

Microphones played a decisive role in shaping vocal style. Crooners benefited from close-miking techniques. These techniques captured breath and nuance. They encouraged softer delivery. Blues and rock and roll singers adapted by emphasizing presence and attack. They learned how to project intensity without overwhelming the signal. These technical realities influenced phrasing, dynamics, and even songwriting choices. They subtly guided artistic decisions.

Limitations also extended to recording length. The physical constraints of singles encouraged concise structures, often around three minutes. This format favored directness and repetition. It reinforced hooks and clear lyrical ideas. Even when the LP allowed greater scope, many artists carried this economy into longer forms. They maintained focus and clarity.

Technology in the 1950s did not aim for perfection. Noise, slight imbalance, and room sound were accepted as part of the recording. These qualities gave records a sense of place and time, anchoring them in lived experience. Far from being obstacles, technical limits helped define the warmth, immediacy, and honesty that continue to characterize the music of the decade.

Major Labels vs. Independents: The Power Struggle

The 1950s music industry was defined by a clear imbalance of power. Major record labels controlled manufacturing, distribution, and access to national media. Independent producers and small labels operated closer to artists and regional scenes. Both sides played essential roles. Their priorities often differed sharply. Majors sought stability and predictability. Independents thrived on risk, speed, and proximity to emerging sounds.

Major labels benefited from scale. They could press large quantities of records. They could secure radio promotion. They could place artists in films and television. This reach came at a cost to creative freedom. Contracts typically favored the label. They granted ownership of masters and publishing. They limited artists’ control over repertoire and release schedules. For many performers, success meant visibility without security. Royalties were opaque. Accounting was inconsistent. Long-term earnings were uncertain, even for popular acts.