Why the 1960s Still Echo Today

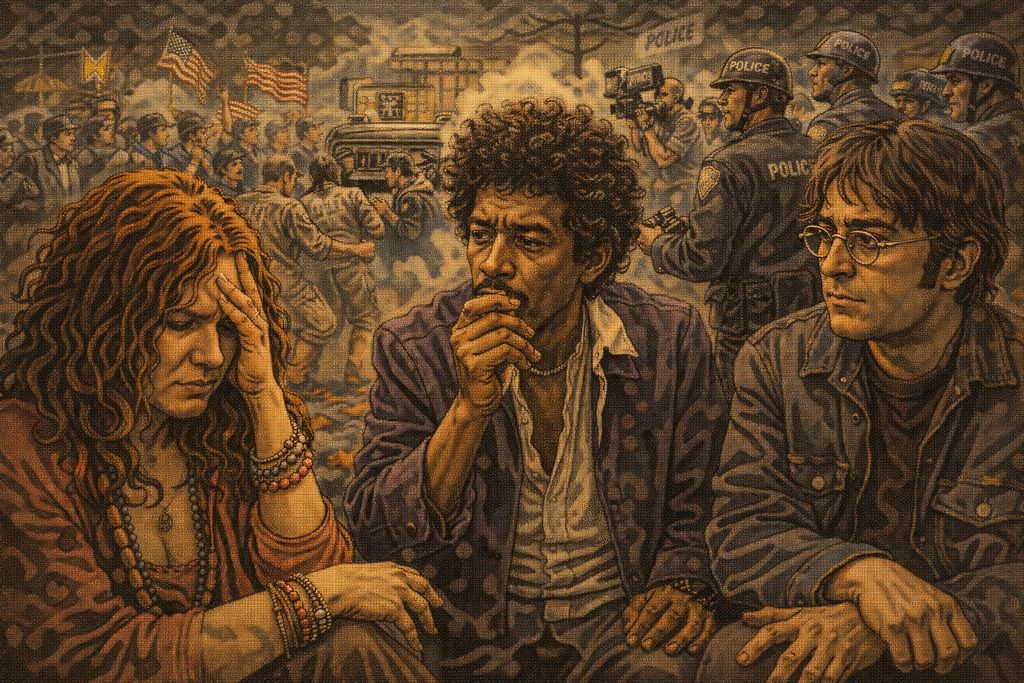

The music of the 1960s is often described as a single, unified moment. It was a time when everything changed at once. The reality was that it was slower, messier, and more human. The sounds that defined the period were not there from the beginning. They came from older traditions, personal struggles, political pressure, and a world that was changing quickly. Artists were trying to understand this world as it was happening.

The 1960s were remembered not just for their innovation, but also for the tension of the times. The decade balanced business and creativity, hope and fatigue, and voices that were heard and voices that were ignored. It produced songs that felt both personal and public. These songs were influenced by social movements, new technologies, and changing ideas about who music was for and what it could say.

The discussion approaches the 1960s without nostalgia or mythmaking. It pays close attention, puts artists in the right historical context, and treats the decade not as legend but as real life.

Setting the Stage: The Calm Before the Storm

At the start of the 1960s, popular music was not revolutionary. It felt planned out, divided into sections, and pretty much what you’d expect. Rock and roll had caused some changes to social norms in the 1950s, but by the start of the next decade, much of its danger had gone down. Record labels preferred artists who were reliable. Radio was popular because it was familiar. Artists were given specific roles. They were either singers, entertainers, or teen idols. They were rarely authors with long-term creative control.

This was a moment shaped by stability on the surface and pressure underneath. After the war, the economy grew. This created a large group of young people with money to spend. The music industry then created efficient systems to sell music to this group. Singles were the most common type of listener. Albums were seen as collections, not statements. Songwriting, performing, and producing were usually separate professions. This meant that power was concentrated far from the artists themselves.

Change was already happening. New voices asked if there were limits to what they could do. Listeners began to lose interest more quickly and had less patience for repetition. Social tensions around race, gender, and age became harder to ignore. The early 1960s were a time of great change. The music sounded like it was supposed to, but the circumstances that created it were about to change forever.

From Rock 'n' Roll to Polished Pop

When the 1960s began, popular music was still feeling the effects of rock and roll’s big debut. The shockwaves created in the mid to late 1950s were still around, but they were now more controlled. What was once disruptive is now being managed, refined, and standardized. The industry had figured out how to present a youthful energy without completely giving up control.

Artists like Elvis Presley were still very influential, but by 1960, they had become much less shocking than they were in the past. Hollywood movies, TV shows, and carefully controlled recordings showed a safer form of rebellion. Rock and roll was no longer seen as an outsider force. It had become a commercial category with clear expectations and limits.

At the same time, important figures like Chuck Berry and Little Richard were seen by the industry as part of an old chapter rather than a movement that was still happening. Their musical style had a big impact on many recordings, but they were not often seen in the media. Racism in the structure of society, the separation of radio programming, and decisions made by broadcasters about what to play meant that Black innovators were ignored just as their influence became undeniable.

A new type of pop performer came onto the scene. These performers were designed to appeal to teenage audiences. Teen idols like Bobby Vee, Fabian, and Frankie Avalon were marketed less as artists with something to say and more as familiar faces that could be trusted. Their songs were short, romantic, and simple. The goal was not to cause conflict or to try something new. The goal was to make people feel better. Music should be enjoyable, not unsettling.

Everyone knew what they were supposed to do, and nobody ever thought to ask questions about it. Songwriters who worked professionally didn’t work on stage. They worked in publishing houses and offices that were far away from the stage. The producers were responsible for shaping the sound. Labels decided when to release music and how to promote it. Performers often played the same role as part of a larger system. The most important things were consistency and sales, not authorship.

Problems were starting to show in this environment, which was being managed very strictly. The people listening lost interest in new music more quickly than expected. Some artists wanted to have more control over their work. In the United States and the United Kingdom, music scenes developed outside of the major record companies’ reach. Small record labels and independent studios experimented with sound because they had to, not because they wanted to.

The early 1960s were not a period of creative stagnation; they were a time of containment. Rock and roll had shown that music could challenge social norms. The pop system that came after tried to stay popular while also being safe. But that wouldn’t last. When new artists came onto the music scene, they challenged not only how music sounded, but also who was allowed to shape it.

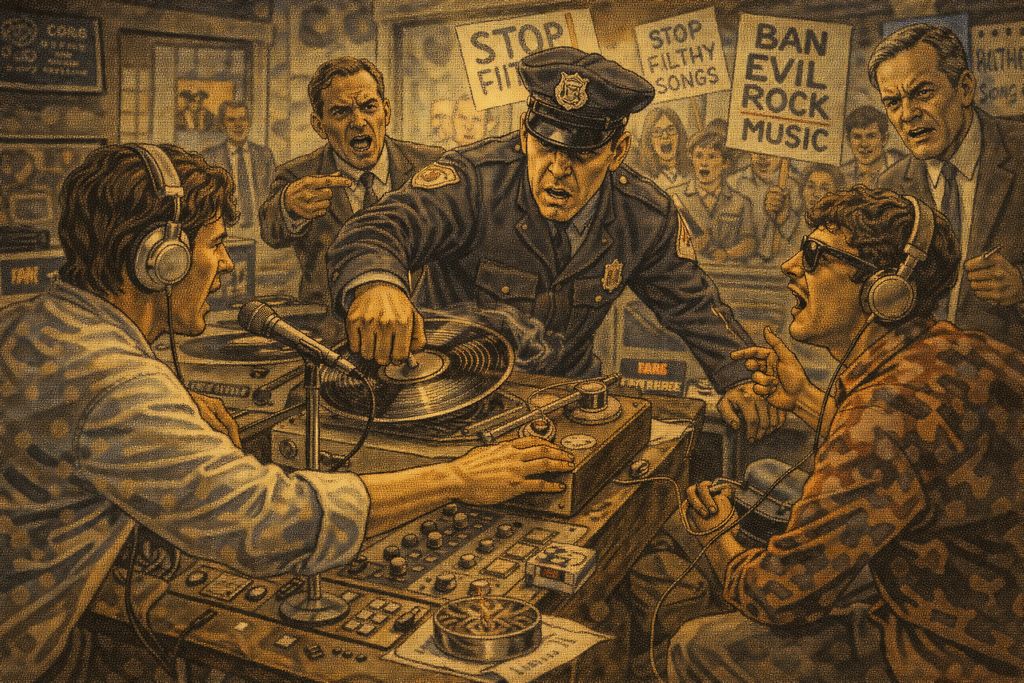

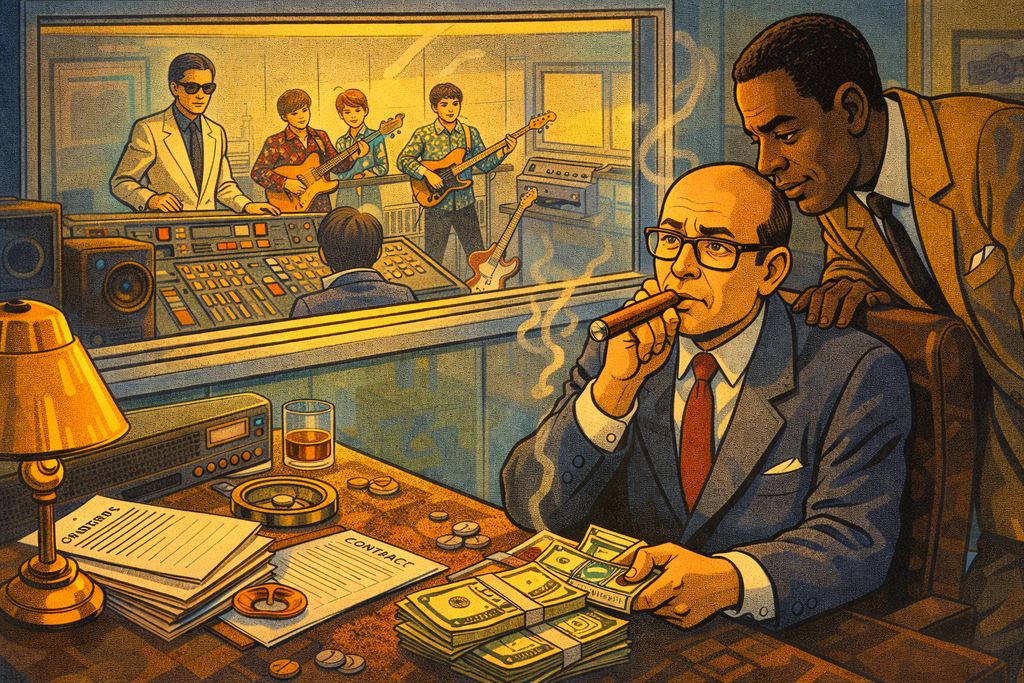

The Gatekeepers: Who Controlled the Airwaves

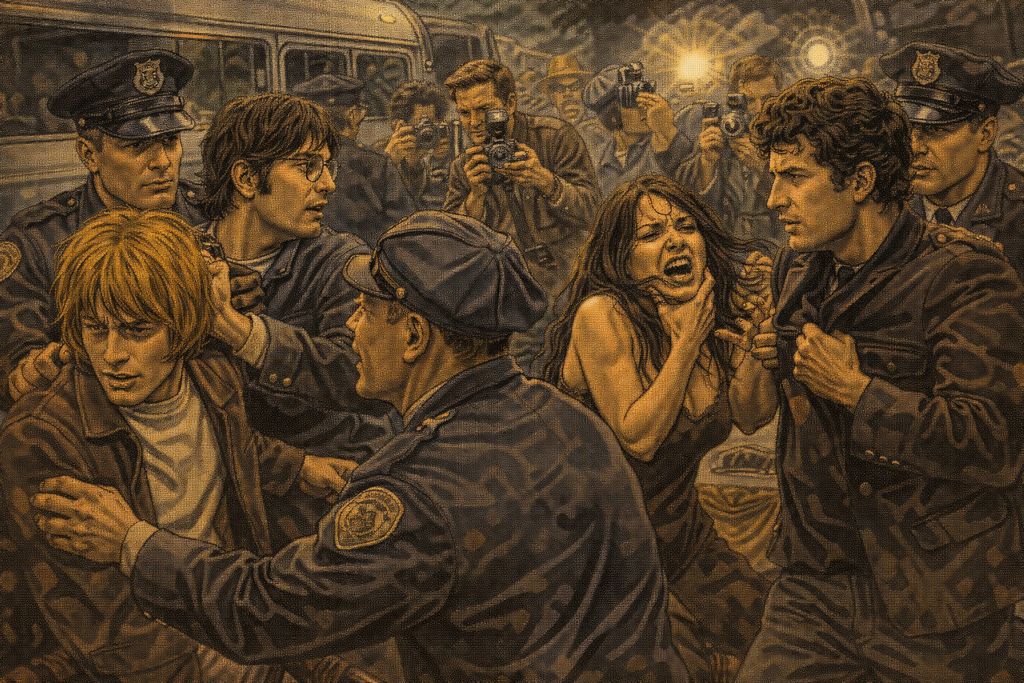

In the early 1960s, it was hard for musicians to make a record and reach an audience. A few big institutions decided what people heard, when they heard it, and by whom. Radio stations, record labels, and TV shows worked closely together. They all liked things that were easy to predict and did not like things that were risky.

AM radio was the most popular way to listen to the radio every day. Playlists were short, and songs were rotated frequently. Also, the songs played depended on the region. If a song wanted to be popular in one city, it had to be played in that city first. Program directors used formats that had already worked well. This meant that new sounds often didn’t get played on the radio. For many listeners, what was popular was the result of repetition and having only a few options.

Television played a similar role. Shows like American Bandstand helped musicians get known all over the country, but only if they fit a certain image. The show was hosted by Dick Clark. It was known for being neat, polite, and family-friendly. The songs on the show were chosen to not upset the advertisers or parents. Being on such a platform could make you famous very quickly, but it also meant giving up some of your privacy. They didn’t play music that had anything to do with politics, race, or strong feelings.

Record labels made these rules even stricter. Major companies were in charge of pressing plants, distribution networks, and promotional budgets. They liked artists who could reliably make popular singles, instead of making music that was different and unexpected. The contracts were unfair. They gave little control to the performers. They also did not consider the financial outcomes for the performers in the long term. The decisions about publishing, production, and marketing were made without the artist’s input.

These structures had a greater impact on Black musicians and women. Even though Black artists played a key role in shaping popular music, radio stations often separated Black and white music. Songs by Black performers were put into the rhythm and blues category and played on different stations. This limited the chance for these songs to be played on other stations. Women were often seen as translators, not creators. They were expected to present material that was written and chosen by other people.

The system was not one thing. Independent record labels, radio stations, and local music scenes offered different options. Small studios let producers and musicians try new sounds without the pressure of a big company. DJs with large local followings supported records that didn’t fit the national trends. These pockets of flexibility mattered.

In the early 1960s, the people in charge of the industry thought they were protecting it. They thought they were making sure it was stable and profitable. The truth is, they delayed a change that was bound to happen. As more people became interested in artistic expression and artists grew more confident in their own ideas, the difference between what art institutions wanted to do and what artists wanted to do became bigger. Musicians who wanted more than just to be famous challenged the traditional structures of popular music. They wanted to be authors, to define their own identities, and to have a voice.

Teenagers, Tunes, and Industry Control

By the early 1960s, young people had become the most important audience for popular music. However, they rarely had real power in the music industry. Teenagers were treated as consumers with money to spend, not as listeners with complex tastes or lasting influence. In the past, the entertainment industry often saw young people’s culture as something short-lived. They thought it was just a phase that should be enjoyed and then left behind.

This perception influenced both sound and image. Songs for young people often talked about romance, wanting something, and a little bit of heartbreak. These feelings felt strong but were kept in check. The lyrics did not talk about social issues directly. The arrangements were neat and familiar. The goal was to create an emotional response that was immediate and didn’t cause any discomfort. Music was meant to reflect what teenagers feel without making them think deeply about who they are, politics, or life after school and dating.

The artists were grouped together in this way. Male performers were presented as friendly and not scary, while female singers were expected to be sweet, calm, and always available. They rarely planned to stay in their careers for a long time. Many acts assumed that their fans would get older and lose interest over time. This short-term thinking made a cycle worse. In this cycle, new things were more important than growth.

Young listeners started to realize that there weren’t many options for them. After the war, people were hopeful, but then they started to feel unsure about the future. The Cold War, the threat of nuclear conflict, and the early civil rights movements created a context that made simple, romantic stories feel incomplete. Music provided escape, but people were starting to expect more from it. When songs didn’t talk about these tensions directly, it was clear that there was a big difference between the experiences people were living and the lyrics of the songs.

Fashion, language, and social behavior all played a bigger role in how people listened to music. Young people used records to show who they were and how they were different, and to find people with similar interests. This was clear in cities, where local sounds and styles developed unique identities. The industry watched these changes closely. Often, they tried to copy them but on a bigger scale instead of letting them happen naturally.

Business expectations were still the main driving force. Labels and promoters thought they knew what young audiences wanted, and they were slow to accept any challenges to that belief. People’s listening habits were already changing. Teenagers liked artists more than they liked individual songs. They liked them so much that they wanted to follow their careers. They cared about how real something was, even if the words to describe it weren’t perfect.

In the early 1960s, the market for young people was both powerful and underestimated. It generated major revenue, but it also had more substance than people thought. As the decade went on, that demand became impossible to ignore. Music would start to show how young people felt about love, society, authority, and themselves. The growing appetite created a shock that spread across the Atlantic.

The British Invasion: When the UK Stormed America

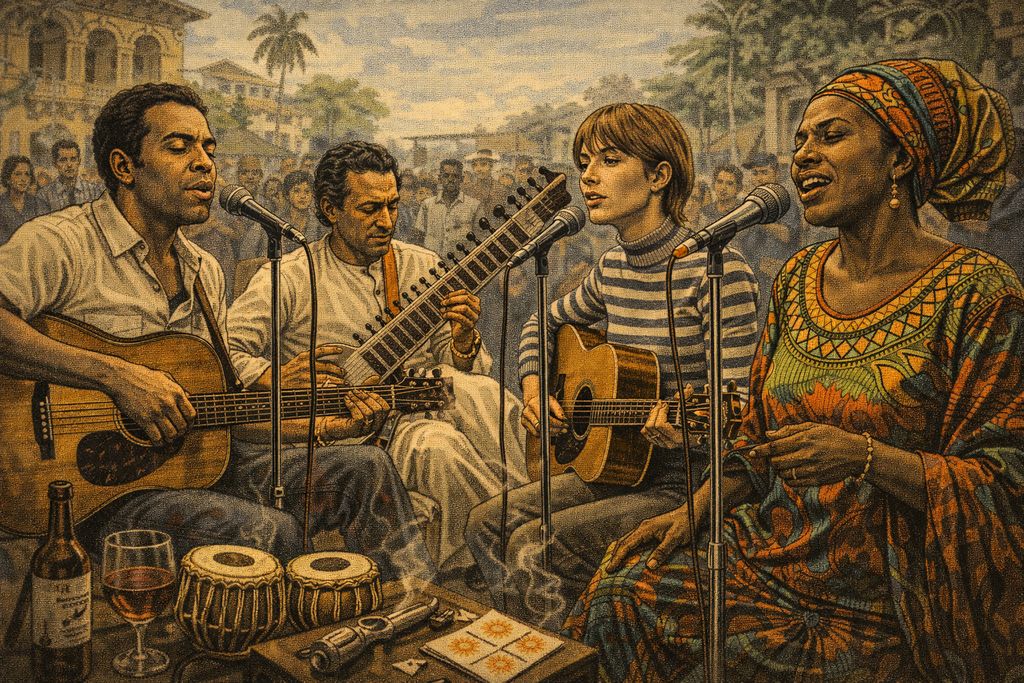

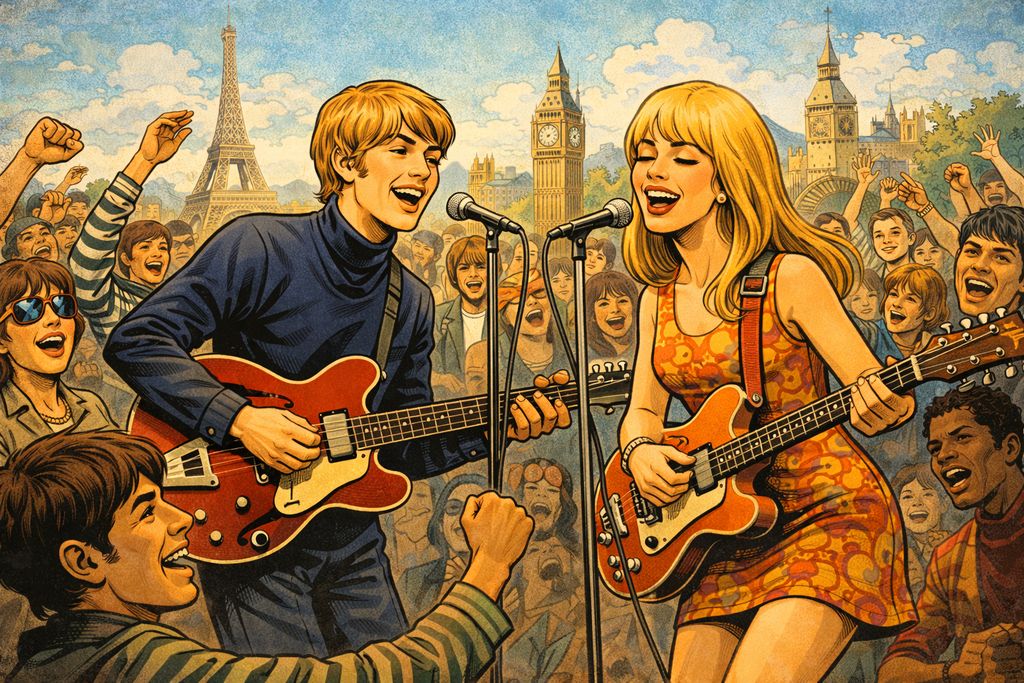

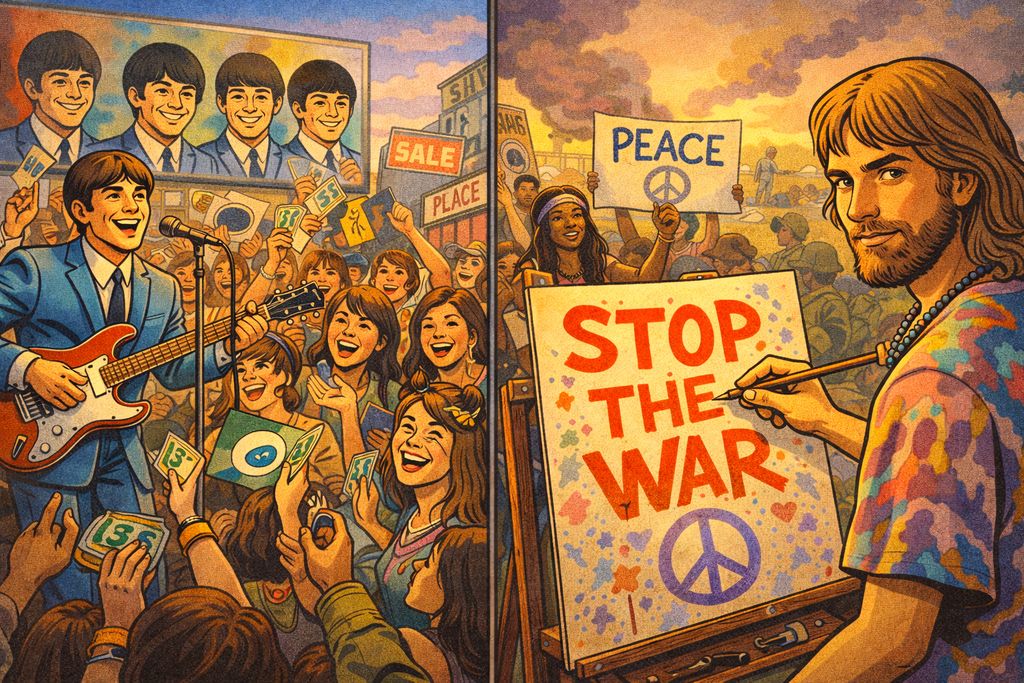

By the early 1960s, British artists were starting to appear on American radio and television. At that time, the pop music world was ready for some new ideas, even if it didn’t realize it yet. The British Invasion was not just one sound or movement. A mix of different influences, ambitions, and cultural views challenged traditional ideas about who could lead popular music and how it could be made.

British musicians grew up listening to American music like blues, rock and roll, rhythm and blues, and soul. They got these types of music through imported records and late-night radio. They looked at these influences from the outside and changed them by adapting them to local scenes, working-class experiences, and different ideas about class, tradition, and irony. When these artists became famous around the world, they brought new sounds and new attitudes. These attitudes were about songwriting, band identity, and creative control.

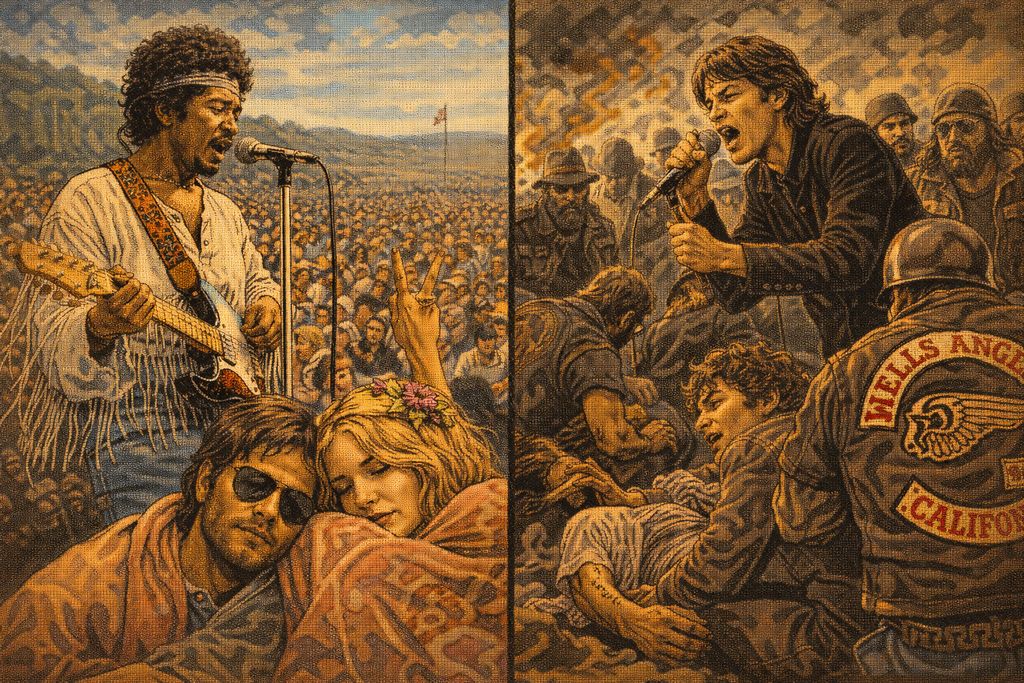

The impact was immediate and far-reaching. Bands became the most important creative groups, instead of just being replacement members. Albums started to matter as cohesive works. Image and sound were considered together when making marketing decisions, not as two separate things. The British Invasion did more than just take the place of American pop music. It made people think differently about what popular music could be and who was allowed to define it.

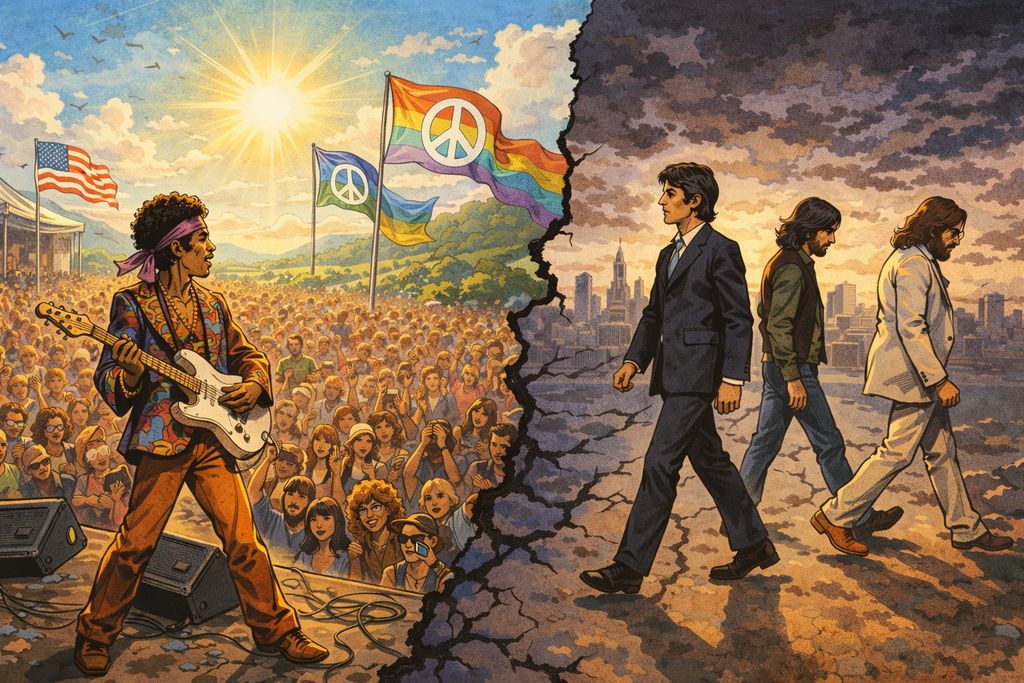

The Beatles: Turning Albums Into Art

When The Beatles first became famous around the world in 1963 and 1964, people liked them because their shows were exciting and full of energy. The news was full of stories about loud crowds, sharp suits, quick-witted humor, and catchy singles. Behind the chaos was something more lasting. The group quietly changed what people thought about who should be an author, what they wanted to achieve, and the purpose of a pop record.

Early releases fit within the established singles-driven market, but they were different because they focused on self-written material. John Lennon and Paul McCartney were more than just performers singing songs they were assigned. They were presented as writers with distinct voices who could evolve and take risks. This was a new way of doing things because usually songwriting and performing were done separately.

As time went on, this challenge grew worse. Albums like Rubber Soul (December 3, 1965) and Revolver (August 5, 1966) showed a clear change in how records were seen. They were no longer treated as random bundles of potential hits. These releases were well-planned, consistent, and designed to discover new things. Songs were linked by sound and intention, not by commercial function. The lyrics explored deeper themes, like self-reflection, uncertainty, and strong emotions. The band combined different types of music, like folk, Indian classical music, soul, and studio experimentation. They did this without making it seem like these types of music were new. Both albums sold well. Rubber Soul was number one on the UK charts for eight weeks and reached number one on the US Billboard Top LPs chart. Meanwhile, Revolver spent seven weeks at number one in the UK and number one in the US, selling approximately 1.5 million copies in its first year.

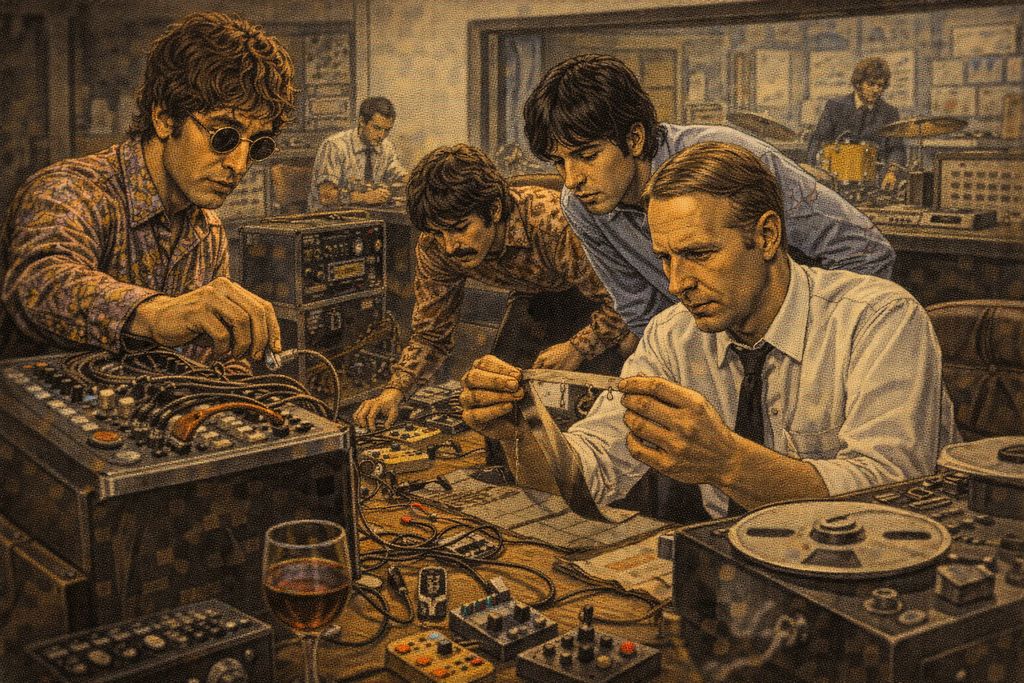

Another important change was the evolution of the recording studio. Producer George Martin helped the studio become a place where creative work could be done instead of a place where only neutral documentation was done. Martin’s classical training and eagerness to experiment allowed The Beatles to push recording technology to its limits. Using tape, playing with instruments in new ways, and putting different sounds together in layers allowed the band to create ideas that were hard to play on stage. Techniques like reverse tape loops, vari-speed recording, and double-tracking vocals became common tools. This change made listeners expect new things from albums. A record no longer had to document a band playing together in one room. It could be imagined, built, and refined over time.

The cultural impact was immediate. Listeners started to think of albums as complete works, spending time thinking about the order of songs, the mood of the songs, and how the songs fit together. Even casual listeners began using new language to discuss records as art rather than simple entertainment. Other artists took note. The idea that a popular band could grow in popularity, experiment openly, and still be popular with most people changed what people thought was possible in the industry.

The Beatles didn’t invent the album as an artistic form, but they made it so that mainstream pop albums could have intention and depth. The album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (May 26, 1967), produced by George Martin, showed how far studio experimentation could go. The album used unusual instruments, like the sitar (on the song “Within You Without You”), harmonium, brass instruments, and tape loops. The recording sessions were more than 129 hours long. They used techniques such as automatic double tracking (ADT), variable-speed recording, and reverse tape effects. Sgt. Pepper was a huge success. It was number one on the UK Albums Chart for 27 weeks and on the US Billboard 200 for 15 weeks. It sold about 32 million copies around the world. It was on the UK chart for 175 weeks. It was the first rock album to win the Grammy Award for Album of the Year (in 1968). They expanded the possibilities for what popular music could be. The album was no longer just a way to release singles. It became a statement, and once that door opened, it could not be closed again.

The Stones, The Who, and The Kinks: Rock's Rebels

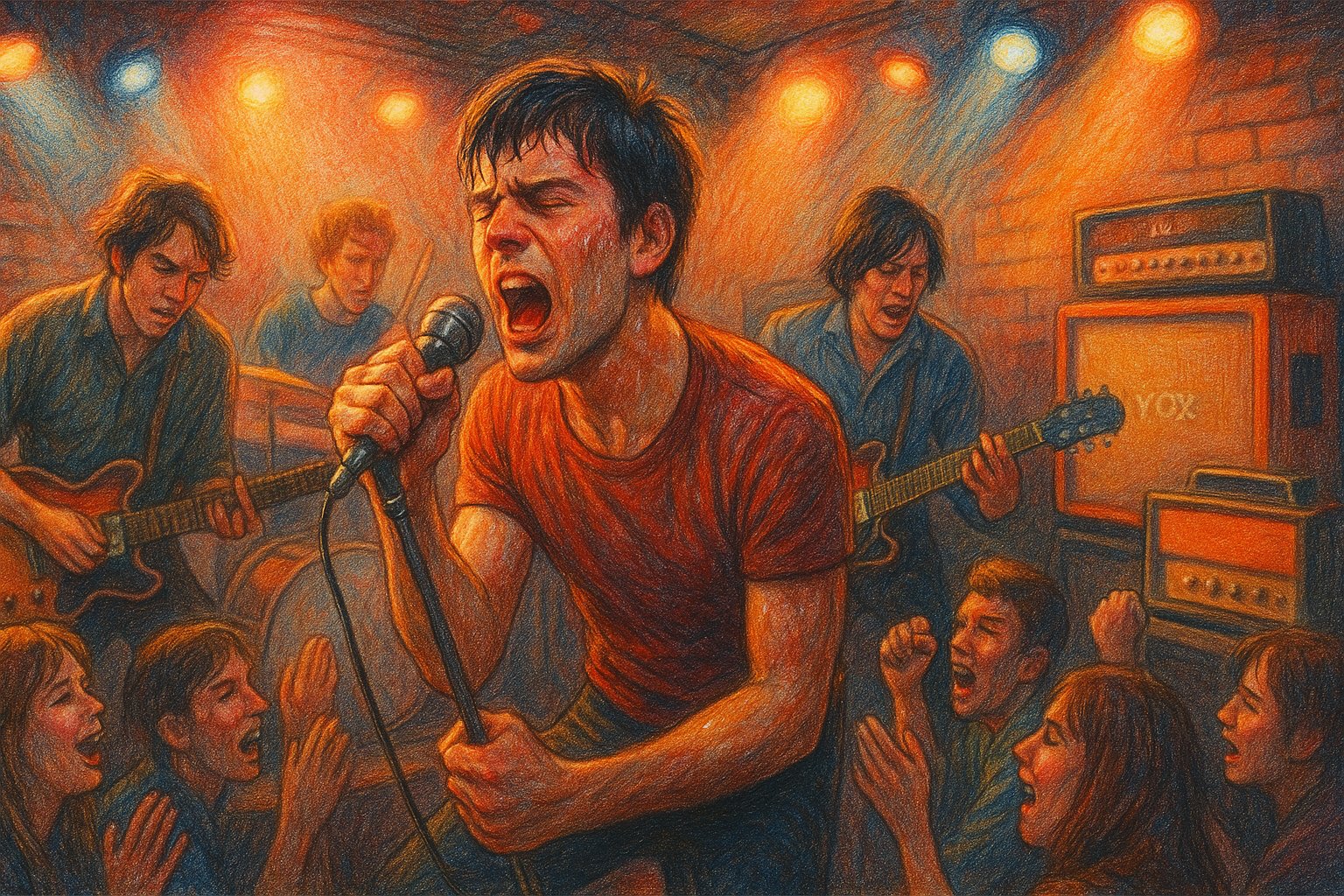

The Beatles made pop music more emotional and formal. Other British bands challenged that style. The Rolling Stones, The Who, and The Kinks were all different, and they showed how British rock could be different from each other. Their music was edgier and more controversial. It wasn’t as popular with everyone. They made the idea of the British Invasion seem more complex. It’s not just a friendly phenomenon.

The Rolling Stones deliberately stood apart from the pop polish of the time. They were heavily influenced by Chicago blues and early rhythm and blues. Their music was known for its focus on grit, sexuality, and unease. The song “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” (1965), written by Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, captured the feelings of restlessness that many people had when they felt disconnected from consumer culture and social rules. The song’s distinctive fuzz guitar riff was an accident. Richards was trying to record a clean guitar part, but the distortion was caused by a faulty Gibson Maestro fuzz-tone unit. “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” was the band’s first big international hit. It reached number one on the Billboard Hot 100 for four weeks and topped charts in multiple countries, including the UK, where it was number one for two weeks. It has sold over 2 million copies in the US and was ranked number 2 on Rolling Stone’s list of the “500 Greatest Songs of All Time.” The band’s image showed danger and defiance. This was not just a pose; it was a reflection of deeper cultural tensions. Their success showed that audiences were ready for music that wasn’t meant to make them feel safe or comfortable.

The Who had a different approach. Their early work combined clever lyrics with energetic performances. The songs often discussed topics such as frustration, personal identity, and disagreements between generations. The song “My Generation” (1965), written by Pete Townshend, expresses anger that felt both personal and shared. The song was known for the singer’s stuttering vocal delivery, which became an iconic part of the song’s style. It became The Who’s most famous song. It reached #2 on the UK Singles Chart and #74 on the US Billboard Hot 100. In 2006, it was added to the Grammy Hall of Fame and ranked #11 on Rolling Stone’s list of the “500 Greatest Songs of All Time.” The band placed a strong emphasis on volume, physicality, and destruction on stage. As a result, live performances became central to their message. Music wasn’t just something to be heard; it was something to be felt and endured. This approach helped change the way people thought about concerts and showed how important live culture would become later in the decade.

The Kinks looked inside themselves. Instead of focusing on big shows or fighting, they looked closely at everyday life with humor and accuracy. Ray Davies wrote songs that talked about the differences between social classes, the tension between people in the home, and the small amount of dissatisfaction that was present in British society. Songs like “Waterloo Sunset” (1967) and “A Well Respected Man” (1965) showed the world what was going on in society, instead of just being rebellious. Even without overt rebellion, they were still deeply important. “Waterloo Sunset” was produced by Shel Talmy and recorded at Pye Studios. The song features Davies’ complex guitar playing and the unique vocal harmonies of Ray and his brother Dave Davies. The song reached number two on the UK Singles Chart. It has also been voted Britain’s favorite song many times in listener polls. It reminded people of London life in a way that was both specific to the city and relatable to people from other places. The Kinks made pop and rock songs more emotional by treating everyday experiences as if they were important.

These bands were united by who wrote them and what they wanted to do, not by their sound. They wanted to write material that reflected their own views, even when it meant not meeting commercial expectations. They showed that pop music can include contradictions. It could be rough or smooth, intense or calm, but it would still be relevant.

These artists broke down the idea that there was only one popular pop style. They showed that popular music could include different voices and attitudes at the same time. They helped make the British Invasion more than just a passing trend. They changed how musicians thought about their role forever.

British Soul Queens: Dusty, Petula, and Sandie

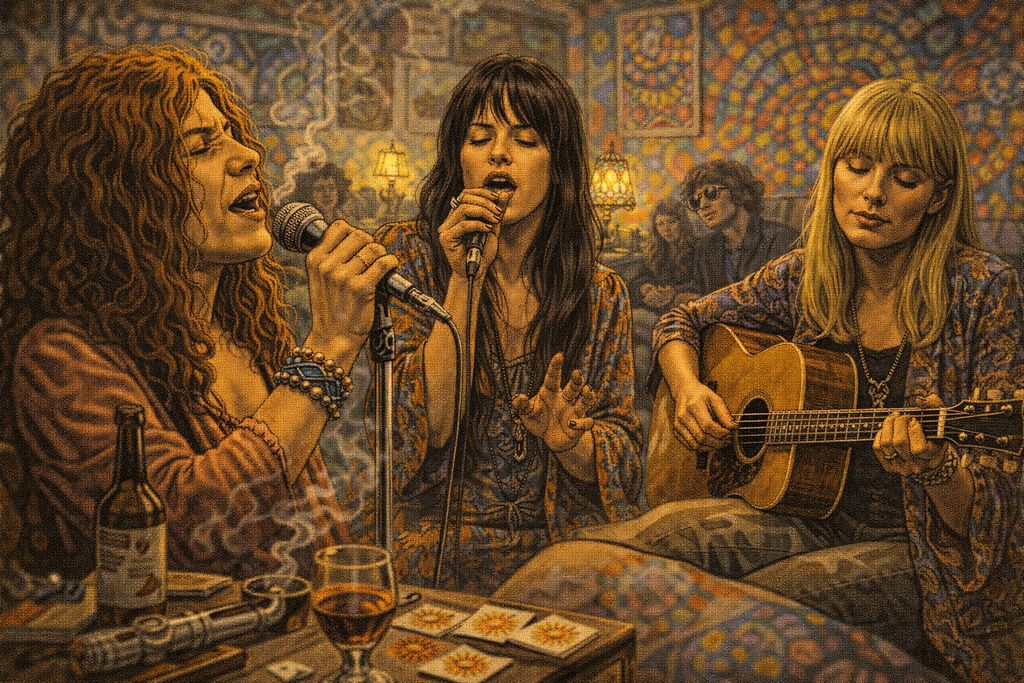

The story of British pop music in the 1960s is often told through bands, but women played an important role in shaping the decade’s emotional range and international popularity. They were successful in part because they had different expectations and limitations. Many of them used these limits to create unique styles that were popular outside of the UK. They were more than just regulars in the British Invasion. They were key to the way it sounded and felt.

Dusty Springfield was one of the most important figures of that time. Her work mixed British pop and American soul music in a unique way, showing great sensitivity and depth. Albums like Dusty in Memphis (January 1969) were produced by Jerry Wexler and Tom Dowd at American Sound Studio in Memphis. The album featured the famous house band, The Memphis Boys. It showed a commitment to emotional honesty that cut through stylistic boundaries. The album included songs written by Carole King and Gerry Goffin (“So Much Love”), Randy Newman (“I Don’t Want to Hear It Anymore”), and others. Dusty in Memphis was a commercial success, but not a huge one at first. It was ranked #99 on Billboard’s 200 album list. Since then, it has been recognized as a very important album. It is ranked #91 on Rolling Stone’s “500 Greatest Albums of All Time” and was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2001. Springfield’s singing style was inspired by Black American soul music, but she never tried to copy it. She turned those influences into something personal and subtle, highlighting vulnerability instead of extravagance. Her success showed the problems in the industry. She is remembered for her voice, but she often had to fit into carefully managed images that hid her artistic ambition.

Petula Clark was different. She was already a famous performer before the British Invasion became popular. She was able to change her style to fit the changing tastes of her audience without losing her own style or control. The song “Downtown” (1964) was written by Tony Hatch and produced by Hatch himself. It offered a sense of optimism about city life that people liked all over the world. The song had a special arrangement with its loud strings and catchy tune, which is what made the “Metropolitan Sound” that Hatch was making for Clark. “Downtown” was a worldwide success. It was number one on the Billboard Hot 100 for three weeks and was also number one on charts in over 20 countries, including the UK, where it was number one for two weeks. It sold more than 4 million copies in the US and earned Clark a Grammy Award for Best Contemporary (R&R) Single. Clark’s career showed that women can be successful in pop music if they adapt to the tastes of the audience instead of trying to come up with new styles. Her success depended on her ability to fit in an industry that was more focused on consistency than on taking creative risks.

Younger artists had even more restrictions. Sandie Shaw became famous for performing without shoes and for not drawing much attention to herself. She was marketed as someone you can talk to and someone who looks modern, but they rarely marketed her as someone with artistic authority. Her recordings showed emotional directness, which was seen as a natural charm instead of something she intentionally expressed. This was just one example of how women’s artistic choices were often described as being more instinctive than deliberate.

Beyond their success on the charts, these artists helped shape the evolving language of pop music. They made emotional complexity common at a time when female performers were expected to be simple or sweet. Their recordings explored feelings of loneliness, wanting to be independent, and being calm in difficult situations. These feelings are similar to the way women’s roles were changing during that time.

There was still a difference in the way things were set up that couldn’t be changed. Women were less likely to be recognized as writers, rarely involved in production decisions, and often left out of stories about innovation. They had a big impact on sound and style, but people didn’t recognize their contributions as much as they should have.

British women in pop and soul music did not completely change the system that shaped them, but they did make it more emotionally diverse. Their work made the movement more meaningful. It was often defined by bands and boldness. They reminded listeners that the British Invasion was more than just loud and aggressive. It was also thoughtful, emotional, and had a calming effect.

How TV and Media Turned Bands Into Icons

British artists were successful in the 1960s, and music wasn’t the only reason for their success. It was made bigger, changed, and sometimes warped by media systems that were trying to keep up with the speed and size of global pop culture. Television, newspapers, radio, and magazines for young people all played an important role in turning bands into symbols and moments into movements. The British Invasion was a big deal in the media as well as in music.

Television was especially powerful. Appearances on American shows like The Ed Sullivan Show made them famous all over the country. When British bands traveled across the Atlantic Ocean, they started playing in people’s living rooms in the United States almost at the same time. These broadcasts made it so that things like accents, fashion, humor, and attitude could be part of the appeal. The performances felt new because the context was unfamiliar, not because the music was unfamiliar. British artists seemed confident, in control of their own work, and less polished than American audiences are used to seeing pop artists.

Print media made these impressions stronger. Music papers in the UK had started to use a special kind of language. They talked about pop musicians like they were important cultural figures. They didn’t see them as just another kind of entertainment. When American magazines started doing the same thing, they used that same tone. They described artists as representing larger changes between different generations. The interviews focused on each artist’s personality, humor, and point of view. This coverage helped fans see musicians as people with their own thoughts and personalities, not just as singers on records.

Image and sound became closely connected. People’s fashion choices, hairstyles, and public behavior were seen as ways to express musical meaning. Audiences closely examined bands not only for what they played, but also for how they stood, spoke, and reacted under pressure. This attention could build status, but it could also be limiting. Artists were expected to have a consistent personality, even as their music changed. If they didn’t fit that image, fans and media outlets invested in a particular story might be upset.

The transatlantic exchange worked in both directions. British artists drew inspiration from American blues, soul, and rock and roll music. In response, American musicians embraced a newfound confidence and bold experimentation, drawing from the vibrant musical scene in the UK. This feedback loop made change happen faster. Scenes grew faster, ideas spread more quickly, and competition pushed artists to do their best. The media was not balanced, so some voices were heard more than others. White British bands were more popular than Black American artists whose work had inspired them.

The media rarely talked about these complexities as they were happening. The coverage gave more importance to the idea of forward movement than to the idea of taking a moment to think. We celebrated success stories, but we did not look closely at the differences in power between different groups. British artists were so visible that people had higher expectations. It showed that pop music could be international and still be unique, and that cultural exchange could change mainstream taste.

By the mid-1960s, the British Invasion was no longer new. It had become a staple of popular music. The media stopped paying attention, but the changes it helped start continued. Attention shifted toward image, authorship, and global influence. Popular music entered a new phase. In this new phase, sound and representation traveled together. Local scenes could resonate far beyond their point of origin. In the United States, artists increasingly claimed the right to write their own material.

American Songwriters Finding Their Voice

As British artists changed the global pop conversation, a similar change was happening in the United States. It didn’t arrive with the same shock factor, but it was just as impactful. American musicians claimed a different kind of authority. They based this authority on authorship, perspective, and the belief that popular songs could carry personal and political weight without losing their audience.

One clear sign of this shift is the growing importance of the songwriter. Lyrics were no longer just there to be sung along with the melody. They became important places where people had different opinions and discussed what it meant to be a part of a group. Folk music, which has always been a part of communal tradition, is now popular and is used to express what’s happening in the world today. Pop and rock artists wanted to write their own songs. This went against the industry’s long-standing division between creators and performers.

The American scene in the early and mid-1960s was marked by contrast. Optimism and anxiety existed together. Songs reflected the civil rights struggles, conflicts between generations, and search for authenticity in a culture that was rapidly becoming more commercial. Authority was no longer seen as coming from institutions or producers. Artists claimed it one song at a time.

Bob Dylan: When Lyrics Became Literature

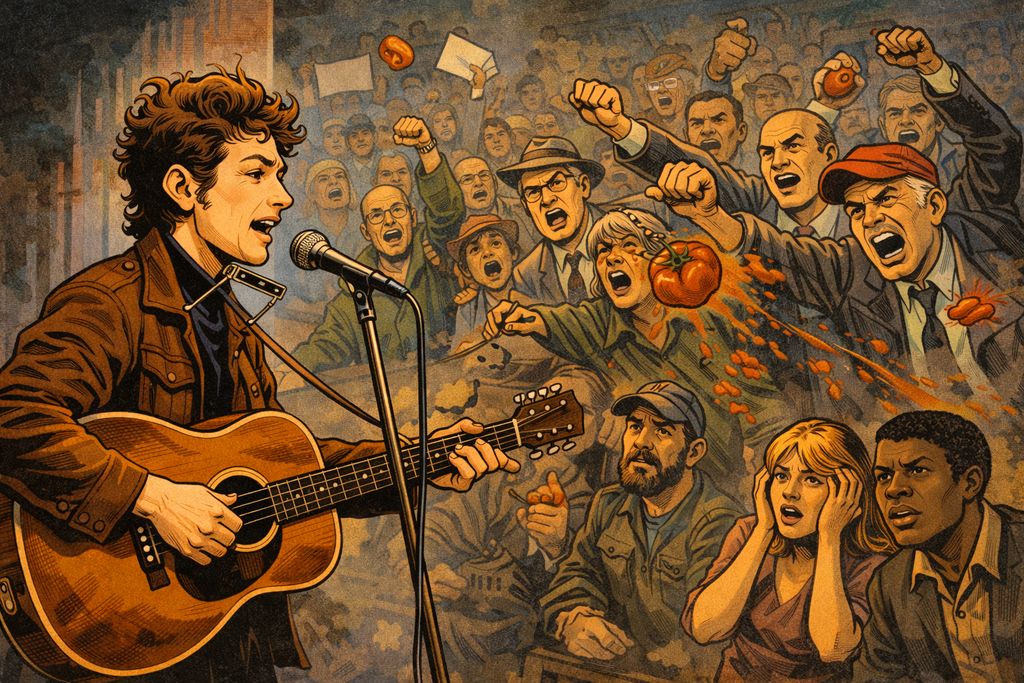

When Bob Dylan burst onto the scene in the early 1960s, he shocked people by defying expectations. Folk music is usually thought of as a type of music that is sung by a community. It is a type of music that has been passed down through generations and changed over time. Dylan entered that space as a writer who saw songs as personal statements. He thought that songs could be argued, ironic, and contradictory. His presence made people focus less on how he performed and more on the language itself.

Early recordings showed him as part of the folk music world, but the lyrics suggested something else. Songs like “Blowin’ in the Wind” (1963) and “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall” (1963) talk about how important it is to be moral, but they don’t give easy answers. They asked questions, but didn’t give any answers. This approach was popular during a time of social tension, but it also caused some people to feel uncomfortable. Dylan was made to act as a spokesperson, even though he didn’t ask for the job or agree to it. The weight of his words showed how much audiences wanted music that deals with real-life issues.

As his writing became more complex, the controversy surrounding it grew. Dylan’s choice to transition from playing acoustic folk music to performing with amped-up sound forced people to think differently about what makes something “authentic.” Some listeners felt that electric instruments were a commercial betrayal. For others, they showed an honest response to the changing music world. Albums like Bringing It All Back Home (1965) and Highway 61 Revisited (1965) showed that rock music could use complex, literary lyrics without losing its energy or making it hard to understand. The shift wasn’t a rejection of folk values; it was an expansion of where they could exist.

Dylan’s work was influential because it refused to become clear. His lyrics mixed personal thoughts with observations of society, humor with sadness, and closeness with distance. This uncertainty allowed listeners to relate to the songs in their own way, making them feel connected without feeling restricted. It made the relationship between the artist and the audience more complicated. Dylan didn’t want people to see him as a guide or leader, even though his work was considered important to the culture.

Other musicians quickly felt the impact of this change. Songwriters took more risks with language. They trusted that audiences could understand complexity instead of simplifying it. Rock and pop lyrics became longer, more detailed, and more emotional. Listeners started to think that a song could be a real form of writing, not just something fun to listen to.

Dylan did not change songwriting alone, but he changed how it was judged. He argued that lyrics could matter even when they made audiences uncomfortable. That shift helped define popular music as a place for both thought and feeling, and its effects lasted far beyond the decade.

The chart impact made that shift visible. “Blowin’ in the Wind” (1963) became a major civil-rights-era symbol and reached #2 on the Billboard Hot 100. Songs like “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall” (1963) showed that urgency could live alongside ambiguity, giving listeners questions rather than easy answers.

As his writing grew more layered, so did the debate around authenticity. Dylan’s move from acoustic folk to amplified rock unsettled part of his audience, while others heard an honest response to a changing musical world. Bringing It All Back Home (1965) reached #6 on the Billboard 200, and Highway 61 Revisited (1965) reached #3, with “Like a Rolling Stone” climbing to #2 on the Hot 100.

What made his work influential was its refusal to settle into one clear meaning. His lyrics held irony and sincerity, intimacy and distance, often in the same verse. That ambiguity gave listeners room to interpret songs personally while still feeling part of a shared moment.

Other musicians quickly absorbed this lesson. Songwriters took bigger linguistic risks and trusted audiences to follow complexity. Across rock and pop, lyrics grew longer, more detailed, and more emotionally layered, reinforcing the idea that songs could also function as serious writing.

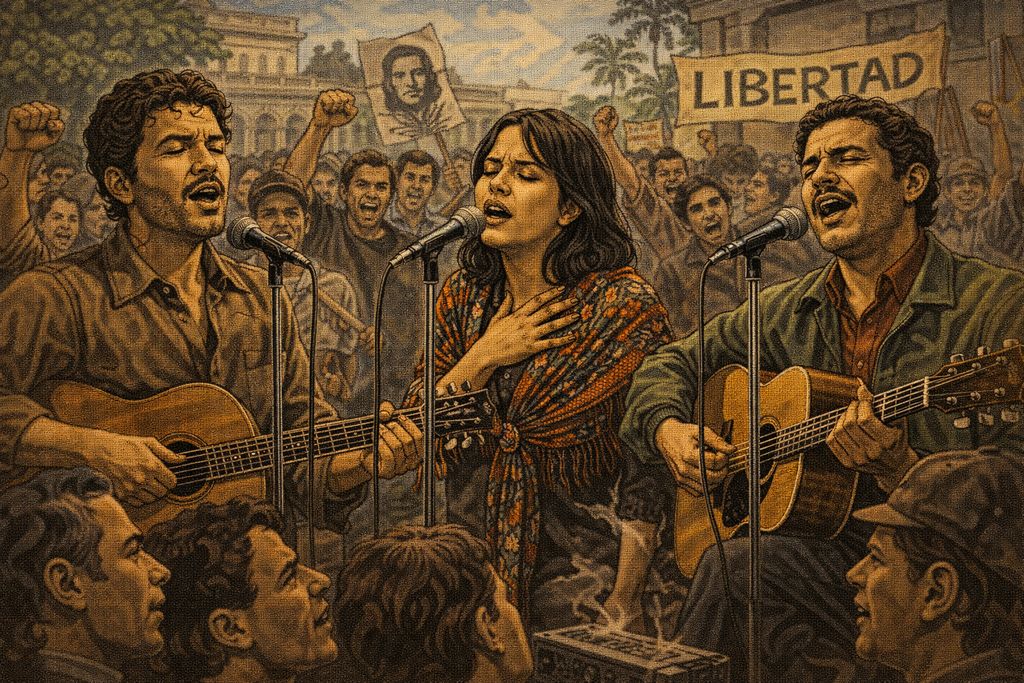

Folk's Many Voices: Beyond the Solo Singer

Bob Dylan was the most famous person connected to the folk revival, but the movement itself was never defined by a single voice. In the 1960s, American folk music was strong because it included many different types of songs. These songs were about different topics, such as community, protest, and personal expression. Many artists used the folk tradition not as a fixed style, but as a flexible way of thinking about the world around them.

Joan Baez was key in bringing folk music to the mainstream while also being clear about her ethical and political beliefs. Her voice was precise and controlled. She sang traditional ballads and contemporary protest songs with the same level of skill. Maynard Solomon produced the early albums at Vanguard Records. Baez’s performances were understated, which made her interpretations seem serious and meaningful. She didn’t see music as a spectacle, but as a form of testimony. Her strong support for civil rights and anti-war activities made people think that folk music could be both art and action.

Peter, Paul and Mary took traditional folk songs and made them more accessible to a wider audience. Their smooth harmonies and easy-to-listen-to music helped songs about social issues become popular on the radio. Albert Grossman produced their recordings. Grossman also managed Bob Dylan. The recordings were made in New York. They were produced very carefully. This made folk songs more appealing to the public. Some critics thought this was a bad idea. But it worked. It showed that messages about justice and togetherness could be part of a commercial space and still be meaningful. They were in a difficult position, trying to be honest but also appeal to a wide audience.

More people were also speaking out. Phil Ochs wrote songs with a sharp political focus. He used irony and direct language to talk about war, hypocrisy, and moral complacency. His work was clear and focused on making a point, unlike Dylan’s writing, which was more open to interpretation. Jac Holzman produced albums like “I Ain’t Marching Anymore” (1965) at Elektra Records. This directness was both admired and resisted equally. Ochs took risks when he wrote political songs. He was often ignored by the music industry because he was too open about his opinions.

Folk scenes were closely tied to specific places. Coffeehouses, small clubs, and college campuses were places where ideas and music were shared. These spaces made people want to listen more than look at their phones. They let songs play slowly and in a meaningful way. The focus on community played a big role in how folk musicians connected with their audience. The performances felt like a conversation, with the performers showing that they cared about the topic instead of just being famous.

At the same time, the folk revival showed that the movement had its limits. Women were often celebrated for their speaking skills, not for their writing. Artists of color had a hard time being seen, even though the genre says it wants to include everyone. As more people moved toward the mainstream, tension grew between traditional ideas and new ideas, and between people who wanted to make a difference and people who wanted to have a stable career.

Still, the band’s impact on the wider music scene was huge. It made songwriting seem like a good way to think about and talk about important issues. It made listeners want to expect meaningful content from popular music. Even though many artists moved beyond acoustic music, the values established by the folk revival continued to influence how music connected with politics, conscience, and shared experiences throughout the 1960s.

California Dreams: The Beach Boys and Studio Magic

While folk music on the East Coast focused on language and conscience, a different kind of change took shape on the West Coast. In California, popular music became closely linked to ideas of youth, freedom, and possibility. Even when those ideas masked deeper uncertainty, they were still present. The sound that came from this place was smooth and easy to listen to, but increasingly ambitious underneath.

The Beach Boys were a symbol of this change. Early hits focused on surfing, cars, and teenage romance, showing a California life that felt easy and bright. These songs were well-crafted and full of harmony, but people dismissed them as unimportant because of the topics they addressed. Most of the songs were written by Brian Wilson and Mike Love, with lyrics by Gary Usher and others. The band’s creative direction changed as Brian Wilson’s growing ambitions took over. Wilson’s work in the studio changed how American pop music was made. He didn’t just see recording as a way to capture live performances. He thought of it as a way to compose music. On Pet Sounds (May 16, 1966), Wilson wrote or co-wrote every song on the album. Tony Asher and Brian Wilson also contributed to the songs. Wilson produced the album and crafted intricate arrangements. The album cost more than $70,000 to produce—a record at the time. The music was created using many layers of orchestration, unusual instruments (like the theremin, accordion, sleigh bells, and bicycle bells), and complex vocal arrangements. All of these elements together created a sound that was deeply personal and emotionally rich. The album dealt with feelings of wanting something, feeling insecure, and uncertainty. These feelings were different from the strong image the band had shown in the past. Recording techniques included new methods, such as recording vocal sections multiple times to create rich harmonies and using studio musicians from The Wrecking Crew, including Carol Kaye on bass and Hal Blaine on drums, to meet Wilson’s high standards. Pet Sounds was a hit when it was first released, but it wasn’t until later that people realized just how important it was. It sold over 2 million copies in the US and was on many lists of the best albums ever made.

What made this change stand out was the situation it happened in. California was promoted as a state of ease and optimism. However, the music coming from its studios revealed feelings of anxiety. Wilson’s growing isolation and need for perfection reflected a larger problem in the industry. Audiences began expecting more from artists. This meant that artists felt more pressure. The industry celebrated new ideas, but rarely supported them in ways that protected mental well-being.

The influence of California’s studio culture extended beyond a single band. Producers and musicians of all kinds paid attention to the possibilities opened by multitrack recording and detailed arrangement. Pop records became more detailed, and listeners got used to sounds that were hard to recreate on stage. The way success was measured changed because there was a distinction between recorded and live music. Albums began to be judged not only by chart performance, but also by whether they could sustain attention over time.

The California sound highlighted ongoing inequalities. Studio experimentation required things like resources, time, and access, but these things were not spread out evenly. Artists who weren’t part of a major record label, especially musicians of color, didn’t have the resources to achieve the same goals. The celebration of studio mastery sometimes hid the structural advantages that made it possible.

The impact of California’s musical shift was undeniable. It showed that American pop music could be thoughtful without losing its fans, and that emotional depth could go hand-in-hand with being successful. These artists helped change what listeners expected from a record by expanding the range of mainstream music. The surface of popular music stayed the same, but it also started to show doubt, complexity, and depth.

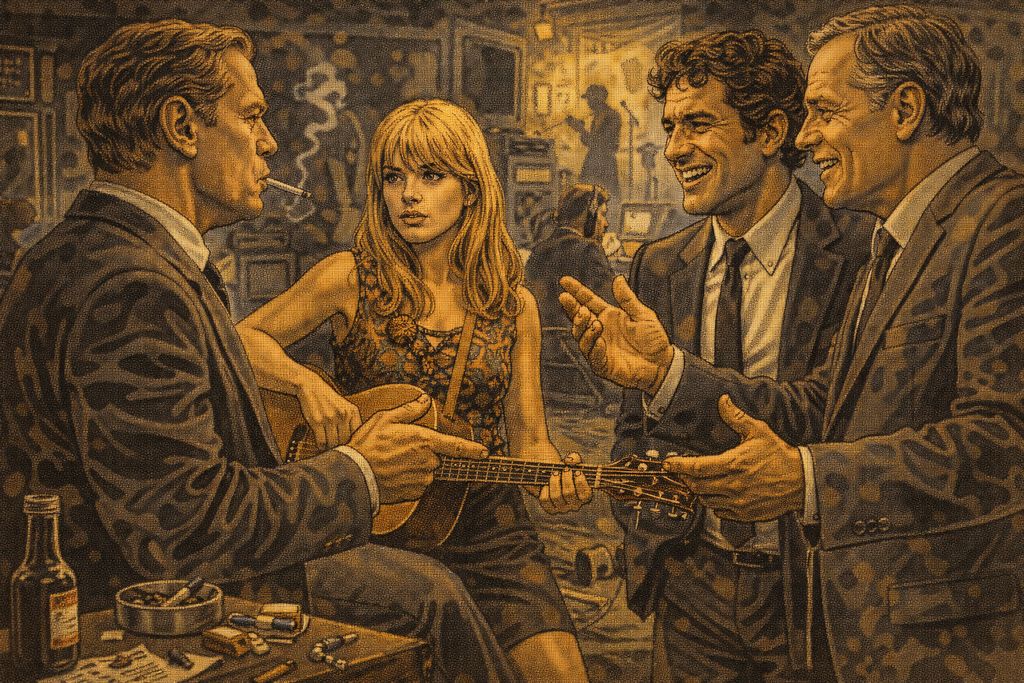

Carole King and the Women Who Wrote the Hits

Even before the singer-songwriter became the most popular type of musician, women were the ones creating the sound and emotional style of American popular music, even if they weren’t the star. In the early and mid-1960s, many of the songs that were on the radio and in the charts were written by women. But these women were not as well-known as their songs. They had a big impact, and they kept on making a difference, even though people didn’t recognize their contributions right away.

Carole King is one of the most important figures in this story. She wrote or co-wrote many hits in the New York Brill Building environment. Her songs were both immediate and emotional. Songs like “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” (1960, produced by Lieber & Stoller for The Shirelles) and “Take Good Care of My Baby” (1961, produced by Snuff Garrett for Bobby Vee) clearly and honestly addressed intimacy, uncertainty, and desire. These were not just random pop ideas. They reflected real life, especially from a woman’s point of view. At that time, this was not common in most songs.

King’s work was part of a larger group of songs and lyrics written by people like Cynthia Weil and Ellie Greenwich. These songs were known for their strong melodies and thoughtful lyrics. They produced material that moved between genres, from upbeat pop to socially aware pieces like “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’” (1964, produced by Phil Spector for The Righteous Brothers) and “Uptown” (1962), with help from partners like Barry Mann and Jeff Barry. These songs were made for a wide audience, but they still had a deep emotional quality that wasn’t simple.

These writers were known for their technical skill and unique point of view. The lyrics focused on the inner lives of women. This was an important development because at that time, female performers were expected to represent specific roles instead of explaining those roles. The ideas of vulnerability, agency, and moral complexity appeared to be very limited by the formats that radio stations could use. This balance required precision. There wasn’t much room for excess or imagination. Every line was effective.

Even though they were successful, these women worked in an industry that rarely saw them as the ones in charge. Songwriting teams were seen as replaceable, and the public preferred performers to creators. Women were less likely to be promoted as creative leaders, even when they produced the same amount or more than their male colleagues. The fact that they were separate—writing and performing—made it easier to ignore the gender dynamics.

The impact was lasting. These songs helped define how love, conflict, and self-understanding are expressed in popular music. They laid the groundwork for later generations of artists who were determined to write and perform their own music. Carole King became famous as a performer at the end of the 1970s with her album Tapestry (1971). It felt like she had been overlooked for a long time, and it felt like it was finally time for her to be recognized.

The women who wrote the American songbook in the 1960s did more than just write hits. They added more emotional depth to pop music while keeping it relevant to commercial success. Their work showed that being skilled and honest are not opposites. Even when they weren’t in the spotlight, their ideas had a big impact on popular music. Their influence met with a larger movement that put Black innovation back at the center of soul, R&B, and gospel-inspired music.

Soul, R&B, and Gospel: Black Voices Rising

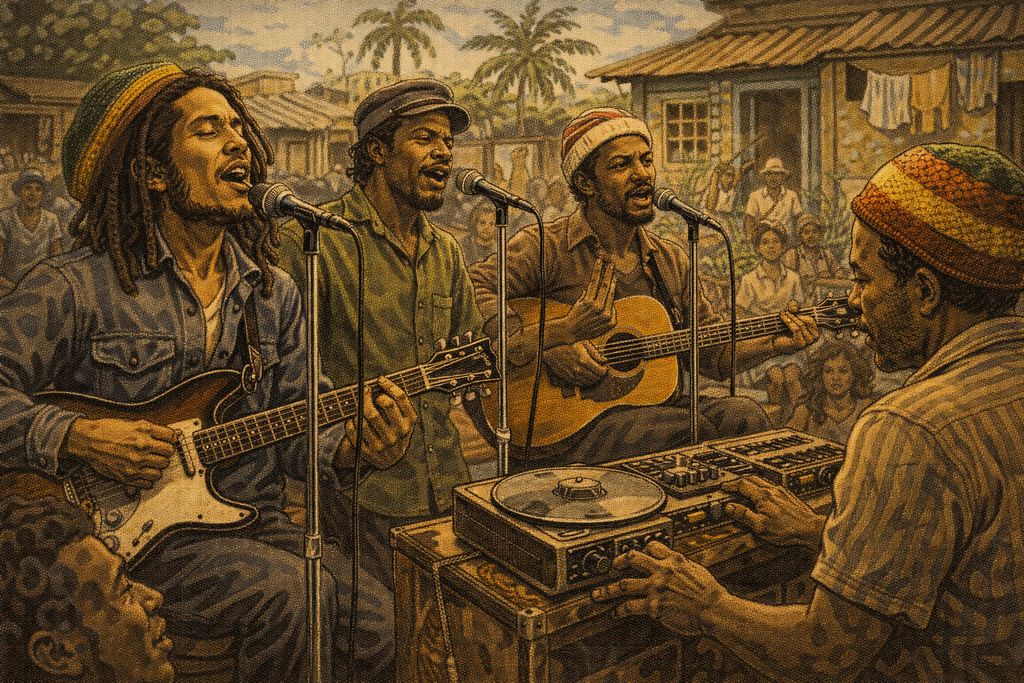

You can’t talk about the 1960s without mentioning how Black American musicians had a big impact on music during that time. They faced many challenges, but they found ways to create, resist, and break through the systems that were holding them back. Soul, rhythm and blues, and gospel-rooted music created a unique sound. They shared their personal experiences during a time of significant social pressure, political struggle, and cultural change.

This music was full of history. The way people sang was influenced by gospel traditions. Blues is a style of music that expresses strong emotions in a straightforward way. Rhythm and blues provided structure and drive. The 1960s brought about a combination of ideas that built on the foundations of the past. This combination was a strong response to the challenges of the present day. Songs addressed love, faith, dignity, frustration, and pride in a way that felt personal and shared at the same time.

The music industry often tried to limit this music to certain categories. This made it hard for the music to reach new audiences. But the artists themselves often went beyond the usual limits. They reached audiences that went beyond the usual limits. Their work had a big impact on pop, rock, and global music culture, even though they weren’t recognized or paid for it.

At the center of this story is Black innovation, not a side note. The focus here is on how artists dealt with the business side of music, stood up for their own creative style, and changed popular music from within. The story of 1960s soul and R&B music is about more than just sound. It’s about authorship, resilience under pressure, and the desire to be heard with dignity.

Motown: Detroit's Hit Factory That Changed Everything

When Motown Records started to be the most popular on the charts in the early 1960s, it did something that was rare for record labels. It made Black American music a central part of global popular culture without forcing it to lose its unique identity. Berry Gordy started Motown in Detroit on January 12, 1959. He believed that soul music could be popular with people of all races and nationalities while staying true to its origins.

Motown’s success came from its organization, not just its talent. The label had a clear internal system. This system focused on songwriting teams, in-house musicians, and strict quality control. The Funk Brothers were Motown’s studio band. They played a steady, recognizable rhythm on the records, but each record sounded different. This made it possible for each artist to have their own style while still being part of a group.

Artists like The Supremes, Marvin Gaye, and Stevie Wonder became famous around the world. Their songs were played on different kinds of radio stations, which helped Black music reach new audiences. Hits like “Where Did Our Love Go” (1964, written and produced by Holland–Dozier–Holland), “My Girl” (1964, written by Smokey Robinson, produced by Robinson and the Miracles), and “Uptight (Everything’s Alright)” (1966, written by Sylvia Moy, Henry Cosby, and Stevie Wonder, produced by Henry Cosby) were both emotional and well-made. The music felt happy and easy to listen to, but it wasn’t simple. These songs sold a lot. “Where Did Our Love Go” was number one on the Billboard Hot 100 for two weeks. “My Girl” was number one on the Hot 100 and the R&B charts for two weeks each. “Uptight” was number three on the Hot 100 and number one on the R&B chart.

Motown also placed strong emphasis on presentation. Artists learned how to move on stage, interact with media, and behave in public. This polish was sometimes criticized as restrictive, but it played a strategic role in a racially divided media landscape. Motown presented Black artists as confident, elegant, and disciplined. They did this to challenge the common stereotypes of Black people and to navigate systems that were rarely welcoming. The approach created opportunities, but it also created pressure to behave in a certain way.

Eventually, there were problems between the label and its artists because the label wanted to control how its artists created music. Marvin Gaye wanted to talk about personal and social issues more directly. This was a sign that artists wanted more freedom in their work. Songs like “What’s Going On” (1971) show this change in style. Gaye produced this song himself. Kenneth Sandusky did the engineering. David Van De Pitte did the arrangements. Stevie Wonder was still a teenager when he first became famous with songs like “Fingertips, Pt. 2” (1963, produced by Clarence Paul). Over time, he gradually took more control over his work. These changes were part of a bigger pattern that happened during that decade. Artists wanted to move beyond the usual roles and express themselves more fully.

Motown’s popularity was global. Its records were spread widely throughout Europe, having an impact on British musicians and contributing to the exchange of ideas between the United States and Europe. The label showed that Black American music could shape popular taste, instead of just following it. But this success also made people ask questions about who owns it, how much profit it makes, and if it will be recognized in the future. Many artists did not earn much money from their music.

Even so, Motown’s lasting success comes from its ability to balance big goals and easy access. It showed that soul music could be both deeply rooted in tradition and widely embraced by many people. By doing so, it changed the sound of popular music and opened more opportunities for Black artists, even though the fight for control and fairness continued.

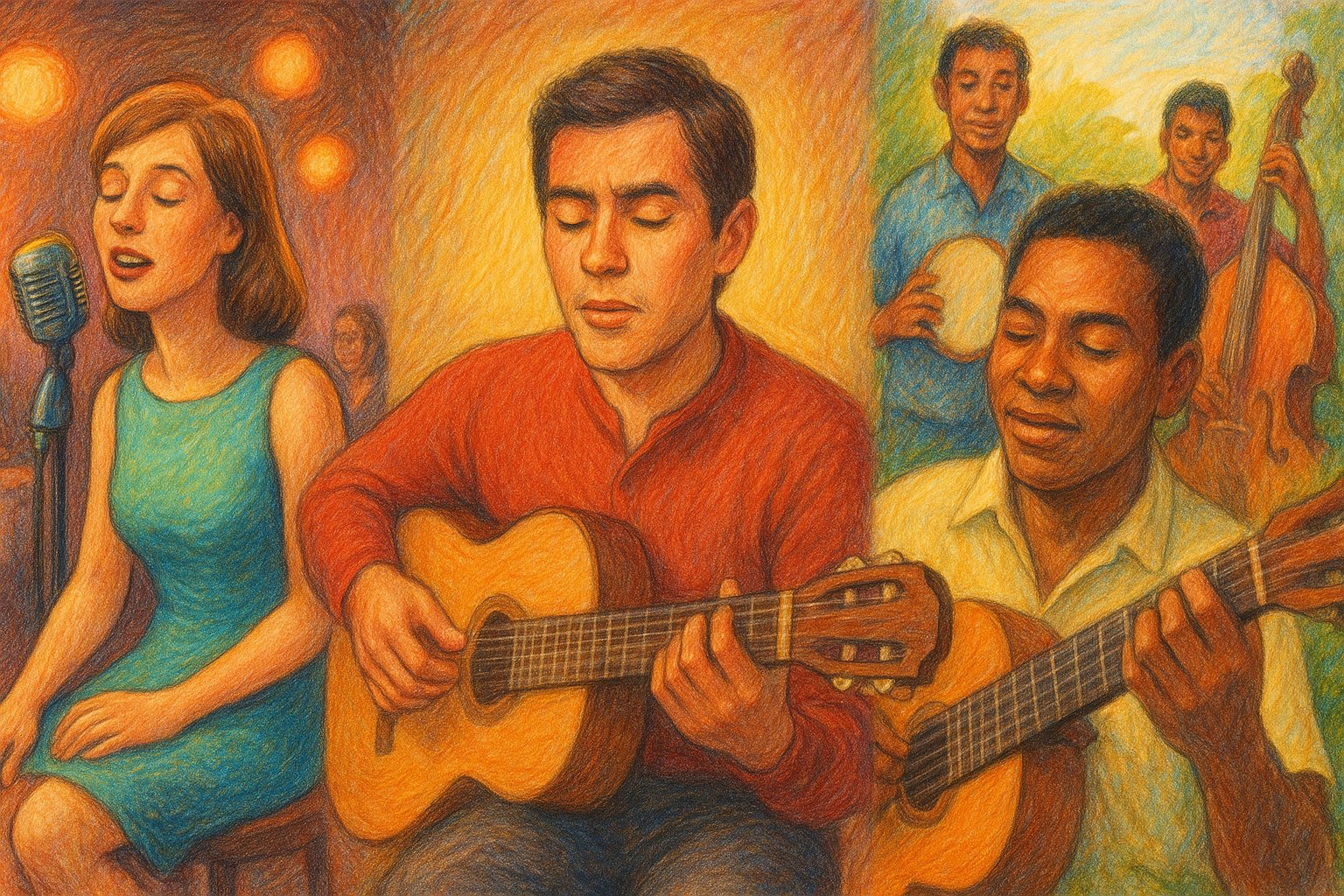

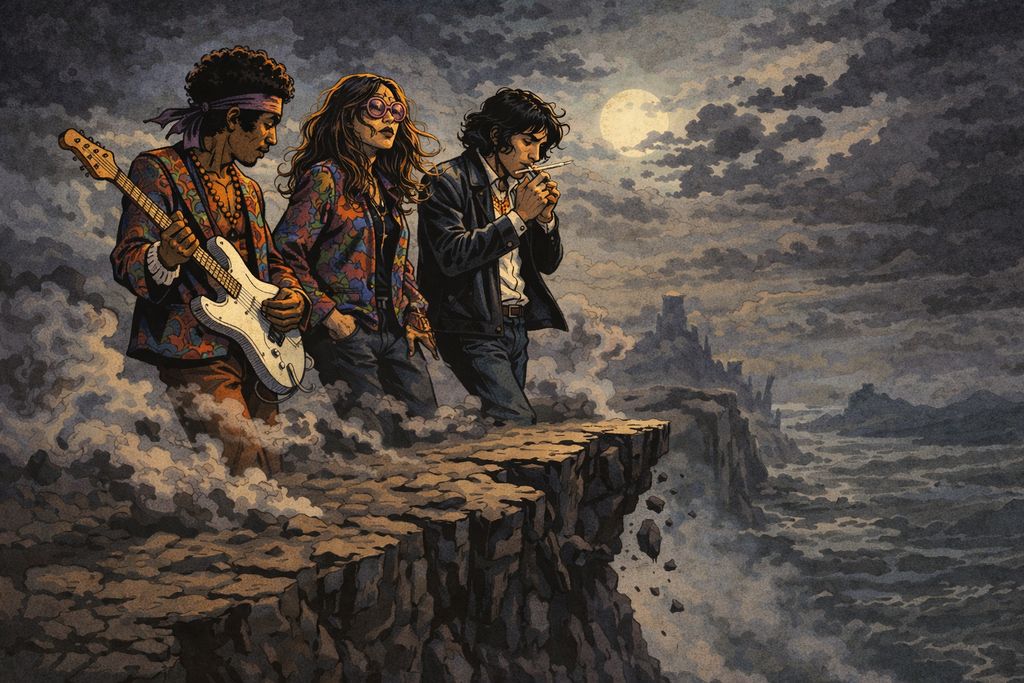

Southern Soul: Raw Emotion From Memphis to Muscle Shoals

Motown was all about blending different styles, while Southern soul had a more distinct and powerful sound. It was honest, straightforward, and didn’t hold back. It was inspired by gospel traditions and the artist’s personal experiences. This music was made in cities like Memphis and Muscle Shoals. It wasn’t made to be liked by everyone. It tried to tell the truth, even when the truth was hard to understand or hadn’t been decided yet.

Gospel music had a big impact on Southern soul. Church music influenced not only vocal technique, but also emotional intention. The singer’s voice was used in different ways, and the words were sung in different ways. The voice was also used to sing very high or very low notes. These were not just for show. They were strong statements of belief. When singers started using these elements in non-religious recordings, listeners could immediately feel the sense of urgency they brought with them.

Aretha Franklin is the best example of this change. She had recorded earlier material that wasn’t very popular, but her move toward a sound rooted in gospel and Southern soul allowed her to express herself in a new way. Songs like “Respect” (1967, written by Otis Redding) and “Chain of Fools” (1967, written by Don Covay) combined strength and vulnerability without compromise. “Respect,” produced by Jerry Wexler and recorded at Atlantic Studios in New York with the Muscle Shoals rhythm section, turned Otis Redding’s original song into a feminist anthem. “Respect” was number one on the Billboard Hot 100 and R&B charts for two weeks each, won two Grammy Awards, and was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1998. “Chain of Fools” was the second most popular song on the R&B chart. It won a Grammy for Best Rhythm & Blues Solo Vocal Performance. Franklin’s voice projected authority through power, phrasing, and emotional precision. She didn’t just sing songs. She was a part of them.

Otis Redding’s approach to Southern soul was different. It was marked by a sense of grit and openness. His recordings often sounded like conversations that were halfway through, with rough edges and emotional outbursts. Songs like “Try a Little Tenderness” build up slowly, so feelings can develop over time instead of just appearing suddenly. Redding’s work focused on building connections. His performances suggested that strength and fragility could exist together, and that sincerity was more important than perfection.

The music industry was supported by labels like Stax Records. Stax was a smaller company. It had fewer resources than major companies. It was important to Stax to work together and be quick. The music was more like a group effort than a factory-made product because the musicians and artists worked together in the same studio and had a friendly relationship. Records were often made quickly, which kept them spontaneous and full of feeling.

Southern soul also reflected the social realities of the South. The American South was a region with significant racial tensions and a strong civil rights movement. Even when the lyrics focused on love or loss, music from this time period carried that weight. Personal feelings and shared experiences were closely linked. The sound itself communicated strength.

Southern soul stood out from the typical crossover style, which was often elegant but controlled. It emphasized presence, urgency, and emotional force. It trusted listeners to understand complexity and emotion directly. This trust was a good choice. These recordings had a big impact that reached far beyond their home regions. They influenced the development of rock, pop, and later soul music on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean.

Southern Soul didn’t try to make itself more popular. It gained influence by staying true to its original ideas. This showed that music based on the gospel was not just for a small group of people — it was a big part of the music of the 1960s.

James Brown: The Godfather Who Made Rhythm King

Southern soul is all about being open and honest with your feelings. On the other hand, James Brown is all about being disciplined, in control, and owning the beat. His impact on 1960s music cannot be measured by genre alone. Brown changed how rhythm worked in popular music. As a result, he changed how identity, power, and presence were expressed on record and on stage.

Brown’s music was a mix of gospel intensity and rhythm and blues structure, but it had a clear, distinct style. The focus moved from melody, which was the main way to express meaning, to groove. The drums, bass, and guitar played in a precise, repeating pattern. Each instrument had a specific role, and every accent was important. This approach demanded attention. It asked listeners to experience time differently and to be physically and emotionally involved.

Songs like “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag” (1965) and “I Got You (I Feel Good)” (1965) were a big change. Brown produced both songs at King Studios in Cincinnati. The music was simple, the beats were strong, and the singing was like drumming. Brown used his voice to create rhythm, not to sing melodies. Musicians started using shouts, grunts, and short phrases to express themselves. The result was music that felt urgent and current. It was focused on the present moment instead of on telling a story.

Brown’s control extended beyond sound. He was a very strict bandleader. Musicians were expected to respond right away to instructions, stay focused, and play with exactness even under stress. Mistakes were not ignored. This rigor wasn’t just about ego. It showed that Brown thought being excellent was a way to stand up to something. In an industry that often didn’t value Black musicians as much as they should have, being precise was a way to show that they were truly skilled.

The cultural implications were significant. Brown’s music expressed a strong sense of self-identity that deeply resonated with the civil rights era. Even though he didn’t talk about politics in all of his work, the confidence in the sound had a political meaning. Rhythm became a way of showing that someone was present. Occupying space and commanding attention through movement was a statement all on its own.

As the decade went on, Brown’s influence spread to different types of music. Rock musicians took his focus on rhythm and stage presence to heart. Soul artists studied his arrangements. The beginnings of funk, which would fully emerge in the following years, were already in place. Brown showed that repetition can be exciting, that discipline can create freedom, and that music with a strong rhythm can have cultural value without needing words to explain it.

James Brown didn’t create his work just to be innovative. He said it was necessary. By doing this, he made the language of popular music bigger and said that rhythm is an important part of who someone is. He helped shape the 1960s in two important ways: musically and structurally. He changed how songs were built, how bands functioned, and how presence was communicated. He was very successful in the music business. Between 1965 and 1969, he released fourteen songs that were on the Billboard Hot 100. These songs included “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag” (#8), “I Got You (I Feel Good)” (#3), and “Cold Sweat” (#7). After rhythm became the most important part of popular music, it would never be the same again.

From Church to Pop Charts: Gospel's Powerful Journey

The line between sacred and secular music has always been somewhat blurred, but it became particularly unclear during the 1960s. Many of the most important singers of the decade started singing in church. There, they learned gospel music and how to feel it in their hearts. When these artists used that language in popular music, they brought a sense of intensity and purpose that changed the sound of the era.

Sam Cooke is an important example of this change. Cooke became famous as a member of the gospel group the Soul Stirrers. He had a warm, controlled, and clear voice. His decision to start making secular music caused some disagreement in church communities. In those communities, people often saw it as a betrayal when someone changed their musical style. But Cooke was just as serious about writing popular songs as he was about writing gospel songs. Songs like “You Send Me” and “Bring It On Home to Me” kept the religious feeling and emotional depth of church music, even though their lyrics talked about love and everyday life.

Cooke’s crossover success helped change what soul music could be. He showed that a product’s commercial appeal doesn’t come at the expense of its emotional strength. His recordings felt personal but weren’t too focused on one particular style. They were expressive but not overly excessive. As time went on, his work started to reflect the world around him more clearly. “A Change Is Gonna Come” (1964) is a great example of how gospel music can talk about social problems in a non-religious way. Hugo & Luigi (Hugo Peretti and Luigi Creatore) produced the song, and it was recorded at RCA Studios with an orchestral arrangement by René Hall. The song was popular because it was honest and hopeful, rather than because of its protest slogans. The song was inspired by Cooke’s experiences with segregation. It was first released as the B-side to “Shake,” but it gained more popularity and became the more well-known message.

Ray Charles had crossed similar boundaries earlier, but his influence continued to be felt throughout the decade. Charles mixed gospel music with rhythm and blues, which was new and different. He did this to challenge ideas about where spiritual expression belonged. Reactions to his work were mixed. The important thing was not controversy, but change. He made popular music more expressive by combining feeling and belief.

These gospel crossover singers changed how listeners understood sincerity. Church singing was emotional and direct, which changed the relationship between the people singing and the people listening. The songs felt like they were performed naturally, not like they were just sung. The singing was full of emotion, with each note conveying a clear message instead of coming across as a mistake. This approach was different from the many pop systems of the time, which preferred a polished neutrality.

The crossover also showed that there are still problems with who owns and recognizes the show. Gospel traditions were shared by the community. They were based on practice rather than on individual authorship. When these sounds started being sold, people started asking about credit, payment, and control. Artists faced these challenges in different ways. They sometimes became more well-known, but this did not always make them more secure.

Even so, gospel-influenced performers had a big impact. They brought back vulnerability and conviction to mainstream music. They reminded audiences that popular songs can be deep and meaningful, even if they don’t have a religious context. These artists combined sacred and secular worlds in their music, creating a new emotional style that influenced 1960s music and lasted for many years.

Who Really Owned the Music? The Price of Innovation

Black American music was very creative and culturally important in the 1960s. But the people who ran the music industry rarely rewarded the artists for their influence. While soul, rhythm and blues, and gospel-rooted recordings influenced mainstream taste, the systems for contracts, publishing, and ownership often worked against the very people who created that value. The difference between the cultural impact and the financial gain was significant, and it wasn’t an accident.

Most recording contracts offered to Black artists during this time had restrictive and unclear terms. There was little progress, royalty rates were low, and it was hard to check the accuracy of accounting practices. Many musicians signed away their publishing rights early in their careers. Sometimes they didn’t understand what this would mean for them later on. These agreements didn’t change how songs were used or who made money from them, even though records continued to sell for decades. Even if a song was successful on the charts, it didn’t automatically mean the artist would be financially secure.

This imbalance was made worse by the fact that different groups of people were not allowed to work together in the same industry. Radio stations often separated music by race. This limited the potential for music to appeal to a wide audience and affected how much money they made from advertising. Black artists could be number one on the rhythm and blues charts, but they were rarely played on pop stations. When crossover did happen, it usually helped labels and distributors more than it helped performers. Sometimes, when white artists perform cover versions, they get more airplay. This makes it even more complicated to figure out who should get credit and how much they should be paid.

Even in successful record labels, the people in charge of the creative side of things didn’t always have as much power as they should have. While companies like Motown and Stax allowed Black artists to reach wide audiences, they also controlled what these artists did. The company decided which songs to produce and release when. Some musicians liked this structure because it made things more stable and visible. Some people found it frustrating as their artistic goals grew. The desire for autonomy was not only creative. It was both economical and symbolic.

Later, artists like Marvin Gaye would challenge these arrangements more openly. They wanted more control over the content and presentation of their work. These efforts were part of a growing awareness that was seen throughout the decade. Musicians were starting to understand that authorship was more than just writing and performing. It included ownership, the ability to tell the story, and the right to define one’s work on one’s own terms.

Women faced even more challenges. Black female artists were often heavily marketed, but they were not involved in business decisions. They helped raise awareness for labels, but they still had little power in negotiations. This made existing inequalities related to race and gender worse, which made it hard to achieve lasting independence.

Despite these challenges, the pressure from artists slowly changed what people expected. By the late 1960s, people were talking more openly about rights, royalties, and creative freedom. The changes were slow and not complete, but they were important. They started making demands about who owns things and how things are done.

The sound of the 1960s was shaped by industry inequality as much as it was by innovation. It affected who was able to try new things, who could take risks, and who could make it through times when business was uncertain. This doesn’t make the music less powerful. It makes it more intense. Black American artists achieved a great deal during this decade, but they had to work hard to do it. They faced many challenges, but they still succeeded. That resilience is part of why this music remains important. It also made it clear how gender would play a big role in shaping the decade’s most prominent voices.

Women Who Shaped the Sound of the Sixties

Women were not a side presence in 1960s music. They were central to the decade’s sound, the range of their emotions, and how successful they were. This was true even when the people around them tried to limit their power. Women were the ones who brought songs to the public. They helped shape how popular music expressed feelings. They also often had careers that required them to be restrained, adaptable, and strong.

But the industry rarely saw women as creative leaders. Female artists were discussed more for their looks, vocal tone, or personality than for their artistic intentions. The song choices, arrangements, and long-term strategy were often decided for them instead of with them. Even so, many women found ways to express their identity in small spaces. Some people did this by changing the words and tone to give their own version of the material. Some people said they were the authors, which made people question who could speak with authority in popular music.

The 1960s also increased tensions around visibility. Even if women are well-known, they might not have much power. They could describe the feelings of a time period while not being included in its stories of new ideas. The following sections trace how women contributed to the music of the 1960s. It does not see their contributions as unusual or separate from the male-dominated story. Instead, it sees their contributions as an important part of the decade’s musical life. It looks at how women dealt with limitations, created music, and left a lasting impact that would only be fully recognized much later.

The Voices That Defined a Generation

In the 1960s, the human voice became one of the most important instruments in popular music. Women played a central role in this change. Female singers made people aware of songs with their emotional performances. These performances taught listeners about intimacy, strength, and vulnerability. Their performances were more than just playing songs. They were among the defining voices of the decade.

Aretha Franklin was one of the defining singers of that time. Her recordings blended gospel intensity with secular themes in a way that felt confident and authentic, not showy. Franklin’s voice was in control of itself, moving easily between holding back and letting go. On songs like “Respect” (1967) and “Think” (1968), she changed existing songs into statements of self-empowerment. Listeners heard not just power, but also intention. Every phrase was important. Her success changed what people thought was possible for a woman singer in popular music.

Dionne Warwick had a different idea. Warwick worked with songwriters Burt Bacharach and Hal David. Together, they developed a vocal style that was precise and emotional. Her performances were calm and measured, with clear enunciation and nuanced phrasing. Songs like “Walk On By” (1964) and “I Say a Little Prayer” (1966) expressed longing and doubt in a subtle way. This restraint made it so that women in pop music could express more emotions. It showed that intensity could be expressed in a subtle way as well as a strong way.

In the United Kingdom, Dusty Springfield offered another example. Springfield’s voice sounded warm and melancholic, and her phrasing was exceptionally thoughtful. Her interpretations were inspired by American soul music, but they also had a personal touch. She sang in a way that made listeners think deeply about the complexity beneath her polished exterior. Springfield’s work showed that emotional depth doesn’t need big, fancy actions. It was alive, in rhythm, timing, and breath.

These artists were united by authority rather than style. Each used her voice to create meaning instead of just saying things the way they are. Their authority was often framed as natural talent rather than deliberate artistic decision-making. News stories focused on feelings and instinct, while ignoring the skills and control that go into making things. This framing made people think more strongly about common ideas about gender and creativity. It suggested that women felt their performances instead of making them up.

Despite these limitations, female singers had major influence. They set standards for how things should be said, the tone, and how emotionally engaging they should be, and they did this in a way that crossed genre boundaries. Male artists studied how they delivered their art. Songwriters wrote with their voices in mind. Listeners connected with the emotional worlds they created.

In the 1960s, women were important figures in music. However, this did not mean that they had the same amount of power when it came to the business side of the music industry. But they did change the sound of popular music. Their voices taught listeners how to appreciate complexity, how to recognize strength in vulnerability, and how to value emotional intelligence as a form of musical authority. Even when their contributions were limited, they had a big impact.

The Songwriters Behind the Stars

In the 1960s, there were many famous female singers. But the women who wrote the songs and helped make them popular were not as well known. They had a big impact on popular music. These women were songwriters, arrangers, and conceptual thinkers. They helped define what pop, soul, and folk sounded like. The industry did not always recognize them as creative authorities.

Carole King is the best example of this hidden centrality. Before she became a famous performer, King’s songs influenced the emotional atmosphere of the decade. She wrote songs that were both immediate and emotional. She did this while working in the Brill Building system. “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” (1960) is an example of a song that talks about love from a woman’s point of view. It doesn’t make the feelings of uncertainty or desire any less intense. These songs were short and easy to understand, but they still had deep emotional meanings.

King’s work was part of a larger group of female writers who helped create popular songs during that time. Ellie Greenwich and Cynthia Weil helped create a list of songs that became the sound of radio during that decade. Their writing combined good taste in music with an understanding of how to express emotion quickly and clearly. Songs like “Be My Baby” (1963, written by Greenwich and Jeff Barry, produced by Phil Spector using his “Wall of Sound” technique for The Ronettes) and “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’” (1964) were emotionally powerful while still being structurally efficient. They were designed to work within the constraints of single-focused markets.

These women worked in professional environments where they had to be able to adapt and control their emotions. Songwriting rooms were places where people worked together, but there was also a chain of command. The people in charge were usually male producers or executives. Women were expected to get results without claiming credit for them. Credit was sometimes shared unequally, and the public didn’t always recognize the contributions as well as they should have. Even when women were important in music, they were rarely seen as the ones who created new sounds.

Despite these limitations, their work subtly changed people’s ideas about gender and authorship. By including female emotional experiences in popular songs, they broadened the range of topics that were considered acceptable. Love was not always seen as something perfect. Vulnerability was not shown as a sign of weakness. Confusion, uncertainty, and choice all had a place in formats made for the general public.

Some women were more determined. They wrote and performed their own material, even though people didn’t support them. Jackie DeShannon took on many roles. She was a writer and performer. She pushed for more creative control in the music industry. At that time, the industry was slow to offer it. Her career showed how hard it was for a woman to be an author during that time.

In the 1960s, female songwriters were key contributors, rather than just having a small impact. They created the musical style, tone, and emotional impact that we recognize across different types of music. Even when their names were only mentioned in the margins, they influenced how popular music spoke about love, identity, and self-understanding. Their legacy became more visible in later decades, but its origins can be traced back to the architecture of 1960s sound.

Image, Control, and the Price of Fame

For women in the music industry of the 1960s, being seen meant meeting certain standards. Success was rarely judged based on sound alone. The way women were portrayed was closely tied to their artistry. This often limited their freedom and made it hard for the public to understand women’s work the right way. Female artists were expected to be easy to understand, comforting, and well-managed, even as their music had deep feelings.

Record labels and management teams spent heavily to control how women looked in public. Everything was watched closely. This included clothes, hair, job interviews, and even personal relationships. This control was supposed to protect people or promote professionalism, but it actually restricted them. If they didn’t, they might face negative business consequences. Female artists had to deal with limitations that male artists did not have to deal with.

These expectations varied across genres, but the basic logic was the same. In the pop music genre, women were encouraged to appear friendly and emotionally open. In the past, strength was celebrated. But it was celebrated only as long as it did not pose a threat. Public discourse could praise assertiveness in public and ask tough questions in private. The difference between how artists were perceived and how they actually performed was especially obvious for artists whose work went against social norms.