Why the 1970s Still Echo Today

When people talk about music from the 1970s, they usually focus on the most famous musicians, the most popular songs, and the biggest myths about that music. Stadium tours, concept albums, disco lights, and punk chaos. But the decade actually began with a sense of uncertainty. The optimism of the 1960s had disappeared. People were more focused on their own personal issues instead of sharing a common mood. Politics felt broken. Institutions appeared unreliable. The idea that music could “change the world” no longer seemed clear.

The shift affected how music was written, recorded, and listened to. Songs became longer, albums became more introspective, and musicians’ careers became more fragile. People no longer expected artists to speak for a generation. Many people only spoke for themselves, and often in uncertain ways. The sound of the 1970s reflects uncertainty as well as aspiration, and withdrawal as well as growth.

To understand this decade, it’s best to stop thinking about revolutions and start thinking about changes. Everyone in the music industry was trying to figure out what would happen next. The music of the 1970s doesn’t give simple answers. It honestly describes that search in the aftermath of the 1960s.

The Morning After: When the Sixties Ended

The change from the late 1960s to the early 1970s was not a smooth transition. Instead, it felt more like a slow exhale after years of tension. The promises that had inspired so much music in the previous decade were still around, but they seemed less reliable. The Vietnam War went on for a long time before it finally ended. The Watergate scandal made people lose trust in political leaders. People’s daily lives were affected by economic uncertainty. Many listeners and musicians started thinking about how to live in the world instead of how to change it.

That change in mindset had a direct impact on the songs people wrote. The loud, proud songs of the late 1960s gave way to more intimate tunes that still packed an emotional punch. Artists continued to be interested in politics and social issues. However, they thought about these issues in a personal way, not in a way that made them sound important. Music helped people deal with confusion, fatigue, and doubt. That change is obvious in the work of artists like Neil Young, whose songs often mix political awareness with emotional openness, and Bob Dylan, who moved away from his role as a protest singer and toward more personal stories.

At the same time, the idea of a single dominant youth culture started to break down. In the early 1970s, listeners moved in different directions instead of sharing one common agenda. Folk, soul, hard rock, and new types of funk and glam did not compete for the same emotional space. They met different needs. Some listeners found comfort and familiarity in the music. For some people, it was a way to escape. For others, it was a way to face challenges. That fragmentation did not weaken popular music. It made it bigger, which meant that more voices and points of view could be heard.

Groups like Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young showed this change in their music. The songs still carried sounds from the previous decade, but the lyrics expressed personal problems, arguments, and ongoing tension. Even success felt complicated. Albums sold really well, but the music was more subdued than exciting.

A new set of priorities emerged. People started to care more about authenticity than about certainty. Complexity replaced slogans. The music of the early 1970s doesn’t sound like a movement marching forward. It sounds like people are trying to understand a world that doesn’t have simple stories to explain it. That uncertainty was not a sign of weakness. It became one of the most important strengths of the decade. It changed how music was presented and enjoyed, encouraging listeners to see the album as a complete work.

The Album Becomes the Statement

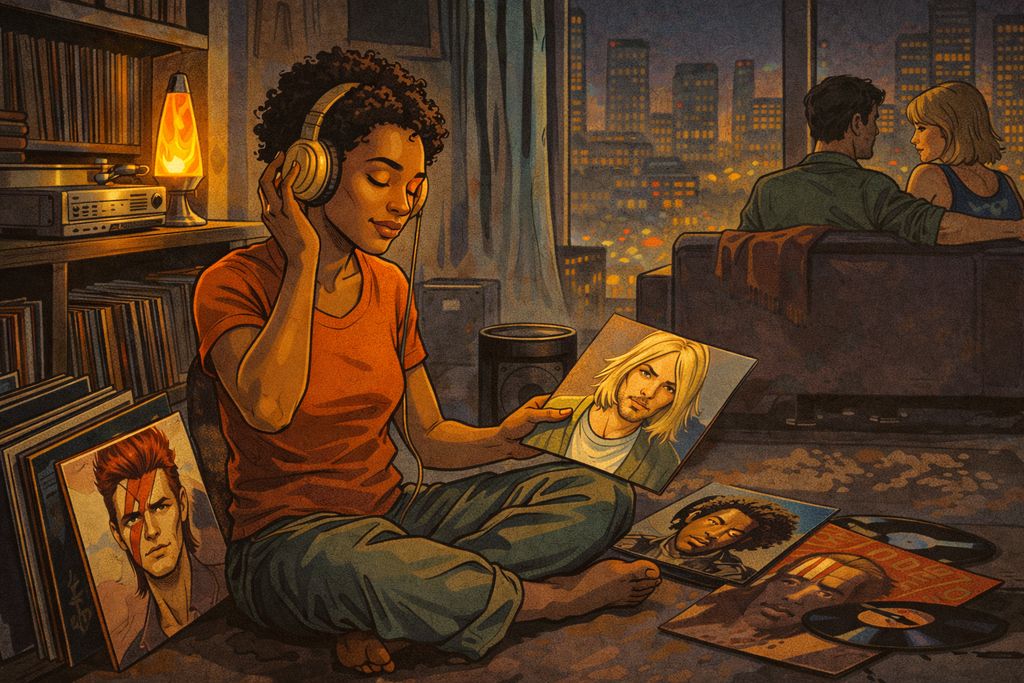

One of the most important changes in the early 1970s involved what artists made and how people were expected to listen. The single had been the dominant format for years. It was short, direct, and made for the radio. It rewarded immediacy and repetition. By the start of the next decade, many musicians were no longer happy with that model. The album became more important than individual songs. It was a clear artistic statement that took time, attention, and patience to understand.

The change is closely related to technology and listening habits. FM radio offered better sound quality and more variety in its programming. That allowed for longer songs and more in-depth content. At the same time, home hi-fi systems became more popular. It made listening to music a private and intentional activity. Music was no longer only something you heard on the radio or danced to at parties. It became something you sat with. That change made artists think about their work in a bigger way, instead of just thinking about each piece on its own.

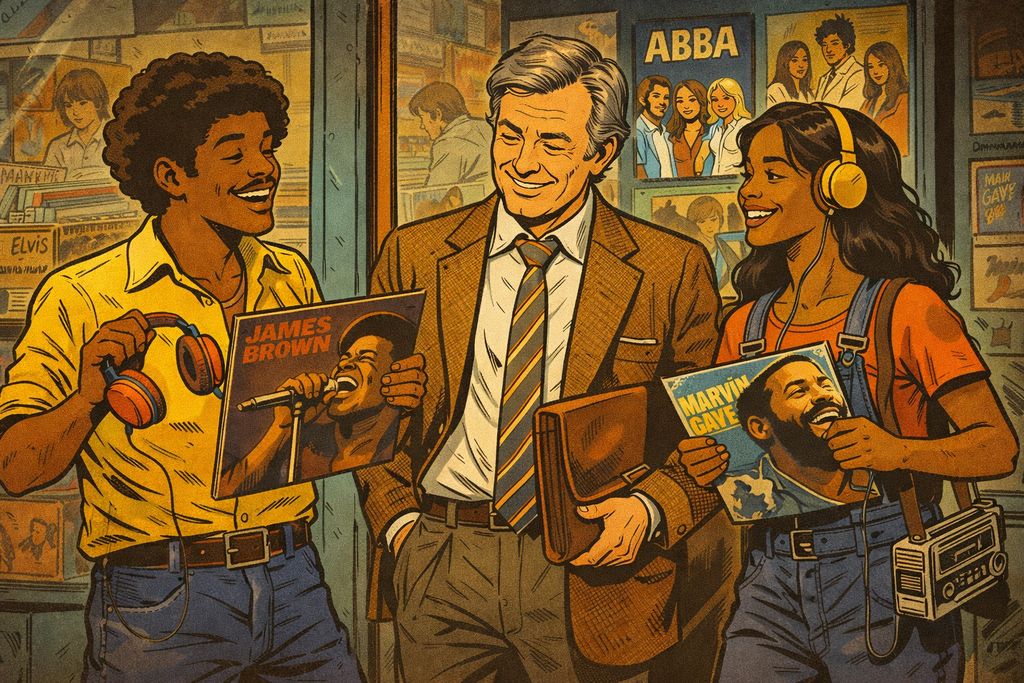

Albums like What’s Going On by Marvin Gaye showed how powerful this format could be. Instead of trying to get individual hits, the record is a unified emotional and political reflection, with songs flowing naturally into one another. Joni Mitchell’s Blue was also influenced by the idea that the order of the songs is as important as each song on its own. These albums are worth listening to carefully. They don’t give all the answers right away; their meaning comes out bit by bit.

Rock music followed a similar path, often on a larger scale. Pink Floyd created entire musical worlds that only made sense when experienced from start to finish. Stevie Wonder used the album format to talk about personal freedom, social issues, and musical experimentation in a way that a single song could never fully do. Each album was a chance to take risks, show ambition, and build a coherent statement.

That meant listeners had to do something different. Buying a record required you to invest not just money, but also time. You learned both the quieter songs and the more well-known ones. You followed the artist’s pace, their changing moods, and their unanswered questions. That way of listening influenced how people remember the music of the 1970s. It’s not defined by a few songs, but by albums that feel like complete conversations, waiting for listeners to hear them in full. As albums became more ambitious, the business around them became stricter.

The Industry Tightens Its Grip

As musicians experimented with new ways to create music and new structures, the music industry went in a different direction. In the early 1970s, major record labels became much bigger. They took over smaller record companies and got more control over how their records were sold, promoted, and played on the radio. At first, this growth seemed like a good thing. Budgets grew larger, studios got better, and successful artists got resources that would have been impossible to imagine a decade earlier. Power became more and more concentrated below that surface.

It became common for musicians to sign long-term contracts with record labels, and these contracts often favored the labels more than the musicians. They had creative freedom, but there were rules. Artists who were successful and made money were supported and promoted. People who did not meet sales targets or challenged expectations too directly were moved to other roles. Executives like Clive Davis were very important in helping artists’ careers. Sometimes, they helped artists by believing in them and helping them grow. Other times, they shaped careers by steering artists in marketable directions. It was hard to tell what was meant by “guidance” and what was meant by “control.”

Motown is a good example of this tension. Berry Gordy was the leader of the label. He had created a system to manage young performers. The system made them into global stars. In the 1970s, many of those artists fought against that structure. They wanted more artistic and personal freedom. The friction that resulted led to the creation of some of the most significant music of the decade. It also revealed how power was distributed unequally. No artist had the power to demand change.

Producers were very important in this environment. Sometimes, they worked with artists to come up with new ideas. Other times, they worked with the people in charge of the projects to make sure the artists’ ideas were understood. Quincy Jones is a good example of someone who played both roles. His work showed how technical skills, musical talent, and industry knowledge could make an artist’s vision stronger instead of weaker. But his success showed how rare it was to find that balance. Many musicians depended on producers and arrangers. These people didn’t appear on album covers, but they greatly influenced the sound of the era.

The system was marked by inequality. Women artists and artists of color often had to deal with extra challenges. For example, they had less money to promote their work and were considered less marketable. Even when their records sold well, they were less likely to have a long-term career. The industry spoke the language of growth and professionalism, but not everyone had the same opportunities to grow.

The 1970s music business was consolidated, which created a paradox that defined the entire decade. It allowed for some of the most ambitious and long-lasting albums ever made, but it also made it harder for the people who made them. It’s important to understand this tension to know why the music of the 1970s sounds the way it does. It is expressive and expansive, but it was often created within systems that were not built to support it. Some artists responded by turning inward, while others pursued scale.

Rock Turns Inward: The Singer-Songwriter Movement

In the early 1970s, rock music was no longer mainly about being loud, fast, or rebellious. A quiet change started to happen. Many artists stopped making big, bold statements and started making art that was more personal. The stage was still there and records were still being sold in large numbers, but the emotional center of gravity moved inward. Rock became a place for thinking, sharing secrets, and looking closely at oneself.

That was not a sign that they were less serious. It was a change in focus. Instead of speaking for groups of people, singer-songwriters started sharing their own experiences. They were often very honest, which felt surprising at the time. Songs explored different relationships, feelings of loneliness, uncertainty, and the challenges of meeting people’s expectations, both in public and in private. The music did not offer any solutions. It provided recognition.

The more personal approach is closely related to the album format and to changes in how people listen to music. These songs were made to be listened to in full, when you’re feeling focused, not as background noise. Rock music was still popular during this time. It changed the meaning of the term. The emotional directness of the singer-songwriter era set the standard for authenticity for many years after, leaving a lasting impact on popular music that extended well beyond the 1970s. That shift laid the foundation for the decade’s more prominent events.

Intimacy as Revolution: Carole King and James Taylor

The singer-songwriter movement of the early 1970s was not a sudden development. It grew out of the emotional exhaustion that followed the previous ten years. Many musicians, whether they wanted to or not, believed that popular music could have a moral impact. By the 1970s, that expectation felt too much. Writing quietly about your own life started to feel more honest than speaking for anyone else.

The change is clear in Carole King’s work. When Tapestry was released in 1971, it didn’t sound radical from a technical perspective. Its strength was its openness. Songs like “It’s Too Late” and “So Far Away” are based on everyday feelings, and they’re sung in a way that feels very real and personal. The album made listeners feel like they were in a private space, and millions of people could relate to that feeling. Its success showed that intimacy, when done well, can be just as powerful as a big show.

A similar way of thinking influenced the music of James Taylor. His early 1970s recordings were reassuring, not confrontational. His voice was calm, and his songs were slow, which made listeners feel like they could trust him. In a time of social uncertainty, that steadiness was important. It suggested that music could still offer comfort without making any promises.

The era was special not just because of what it was about, but also because of the way it was presented. These artists weren’t presenting themselves as heroes or spokespeople. They seemed to be imperfect and sometimes unsure of themselves. That approach was most obvious in Joni Mitchell’s work. Albums like Blue show more emotional complexity than resolution. Mitchell’s songs do not make life easier to understand. They show things that are hard to accept, like mistakes and feelings such as regret and longing, and they do so in a way that can feel a little shocking.

Being honest like that was dangerous. Writing directly about one’s personal life made it difficult to distinguish between public art and private emotion. Some people did not like this music. They thought it was too focused on the artist and not as meaningful as the important music from earlier years. But its ability to last suggests otherwise. These records were very honest, and they changed how people thought about authenticity in popular music. People started to think that being vulnerable was a sign of strength.

In the early 1970s, singer-songwriters did not stop playing a part in the culture of rock music just because they focused more on their own music. They changed the meaning of the word. Their work showed that personal experience is connected to the wider world and deeply influenced by it. That created a model for how popular music could stay meaningful even when things weren’t certain.

Women Claim Their Voice

The singer-songwriter movement is often remembered through a few famous men, but it also had a strong emotional and artistic depth thanks to the work of women who challenged long-standing expectations. In the early 1970s, many female singers chose to write personal songs. For these singers, this was more than just a style choice; it was a way to express resistance against the social and cultural norms of the time. The music industry had always preferred women to be the ones performing the music instead of writing it. It was important to write your own material and insist on being heard.

Carly Simon was a big part of this change. Her songs were honest and insightful, often talking about relationships from a strong, active perspective. The song “That’s the Way I’ve Always Heard It Should Be” was different from other songs because it was honest about social norms around marriage and independence. At that time, most songs didn’t talk about these topics in such a direct way. Simon’s success showed that thinking deeply and thoughtfully can be taken seriously, even if it’s not quiet or modest.

Other artists worked with less commercial success but the same level of conviction. Laura Nyro wrote songs that were full of emotion. They were influenced by soul, jazz, and pop music, and often had unusual structures. Her music required you to pay close attention and be emotionally prepared. Although her work was often praised by other musicians, it was not well-received by the music industry. The industry had a hard time marketing her work because her music was not like the music that was popular at the time. Nyro’s career shows that it’s rare for an artist to have both artistic influence and commercial success.

Judee Sill is a good example of this. She shows how creative something can be, but also how easily it can be destroyed. Her songs combined spiritual images with personal stories, driven by her own difficult experiences and her deep knowledge of music. Even though she was well-liked by critics, she didn’t have much support from institutions, and it was hard for her to keep working. Her story is not unusual for that time. It is part of a bigger pattern where women were encouraged to speak freely and express themselves, but rarely got protection when that expression led to problems.

These artists are united by their belief in the importance of authorship, not by the sound of their music. They wrote from their personal experience, without trying to hide the contradictions or discomfort. That increased the range of emotions that could be expressed through popular music. Their work made room for a variety of feelings, like uncertainty, desire, frustration, and independence. These feelings were expressed by voices that were not easily defined.

The impact of these women will be felt for many years. They changed what people thought about who could tell their own story in popular music. Even when the music industry did not support them, their songs were still played and influenced later generations. These generations saw their honesty and independence as a good example.

East Coast, West Coast: Place Shapes Sound

As the singer-songwriter movement became more popular, it became clear that this inward turn did not sound the same everywhere. Geography was important. The United States, especially, had different regional voices. These voices came from differences in class, environment, and local culture. These were not just ideas. They were a big part of how songs were written, the stories they told, and how artists understood success.

On the West Coast, especially in and around Los Angeles, songs often had a subtle feeling of sadness beneath their polished surface. The music sounded relaxed, but the themes were rarely happy. Musicians like Jackson Browne wrote about being ambitious, feeling disappointed, and being responsible for your feelings. They did this in a way that matched the feelings of the place. Songs like “Doctor My Eyes” and later “Late for the Sky” captured a feeling of searching without finding any answers. The landscape suggested openness, but the lyrics expressed feelings of isolation. Success was possible, but it was also difficult to achieve.

On the other hand, East Coast singer-songwriters often wrote about similar topics in a way that was more connected to society. Billy Joel grew up in a working-class and middle-class environment where music was closely tied to everyday life and struggles. His early songs are about money problems, what your family expects you to do, and the struggle between wanting to be an artist and having to make money. Even when his work later reached a wide audience, it remained focused on everyday life instead of making things seem more romantic.

These regional differences weren’t just about style. They showed class awareness in small but noticeable ways. Many singer-songwriters of the 1970s had time and space to write because they came from backgrounds that allowed it. But their most compelling work often focused on the limits of that privilege. The difference between having creative freedom and not having enough money to support yourself came up a lot. Songs talked about being afraid of falling behind, feeling like you have a lot of responsibility, and not knowing if it’s better to choose art or stability.

These regional voices were connected by their shared rejection of exaggerated heroism. The songs of this era were influenced by the different styles of music found on the West Coast and the East Coast. They did not portray success as simple. When fame first appeared, people often saw it as another source of pressure instead of fulfillment. The audience wasn’t invited to admire a lifestyle, but to recognize a feeling.

By basing their work on certain places and social situations, these artists broadened the range of topics that rock music could cover. Personal storytelling became closely linked to questions of social class and geography. The result was music that felt real and believable, full of emotion and context. Paying attention to everyday details helped make sure that the singer-songwriter era didn’t become too abstract. It remained linked to actual people, places, and the subtle tensions that influenced them, even as rock moved toward bigger stages and bigger statements.

Rock Goes Big: Stadiums, Concepts, and Excess

While some artists were focused on themselves in the early 1970s, others made a big change and did the opposite. Rock music got bigger, louder, and more ambitious. The expansion wasn’t an accident. It showed how far rock music had come, both in terms of technology and in terms of people’s views on it. More and more people thought that rock could be considered a serious art form, just like film, literature, and classical music. Albums became longer, concerts filled entire arenas, and the distance between the performers and the audience grew.

The outward push created confidence, but it also created tension. Some people liked the size and excitement of these shows, but others felt that something important was missing. Intimacy gave way to spectacle. Simplicity was replaced by virtuosity. Rock music started to become an institution in its own right.

But it would be wrong to see this moment only as a time of excess. During this time, the music was driven by curiosity and ambition. Artists experimented with structure, sound, and identity. They often took risks because they knew that sometimes, things could easily fail. Some of those risks paid off. Others collapsed under their own scale.

The growth of rock music in the 1970s can be seen as a test of limits. It asked how far popular music could go without losing its connection to the people who liked it. The answers were inconsistent and sometimes contradictory, but they changed what was possible with rock for many years after that.

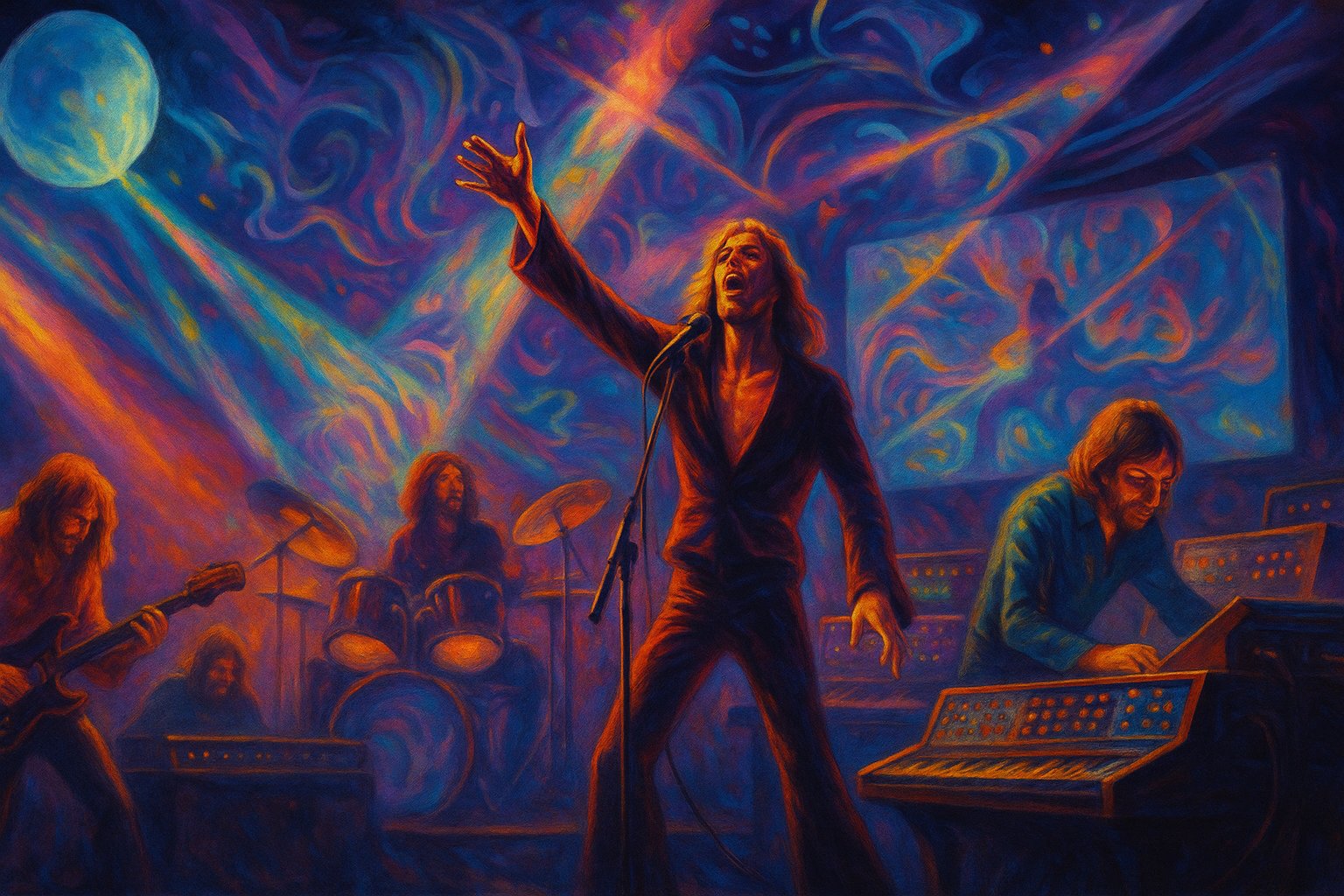

Progressive Rock: When Ambition Met Complexity

Progressive rock became popular in the early 1970s. It was one of the clearest expressions of rock’s growing ambitions. The idea behind it was that popular music didn’t have to fit into a set format or follow a predictable emotional path. Songs could be long, albums could be cohesive works, and influences could come from many sources, beyond blues and folk traditions. Progressive rock was seen as a symbol of freedom and seriousness by its fans. Its critics felt that it was too easy on itself and not close enough to its audience. Both reactions were justified.

Pink Floyd is a good example of this. Albums like The Dark Side of the Moon and Wish You Were Here used the studio itself as an instrument. They did this by combining sound effects, recurring musical themes, and lyrical ideas into carefully designed pieces of music. These records talked about time, mental pressure, missing people, and feeling disconnected. These topics were especially meaningful for listeners who were dealing with a time full of unknowns. Their success showed that you can have big goals and be emotionally relevant.

In the UK, progressive rock also had a strong connection to literature and theater. Bands like Genesis created complex stories that combined elements of mythology, social observation, and surreal imagery. Albums like Selling England by the Pound made people feel nostalgic and worried. They showed a country that was struggling with economic problems and changing who it was. The music was complicated, like the ideas it was trying to express.

At the more technically oriented end of the spectrum, Yes highlighted musical skill. Records like Close to the Edge featured complex arrangements, changing time signatures, and long instrumental sections. Some listeners liked how precise it was. Some people thought progressive rock focused more on technical skill than emotional connection. The difference between admiration and alienation became an important part of the genre.

These artists are united by a shared belief in expansion, not by a shared sound. Progressive rock used the album as a place to try out abstract ideas, philosophical questions, and musical experiments. It expected someone who would listen carefully and who would want to stay with it. That expectation became both its greatest strength and its biggest weakness.

By the mid-1970s, progressive rock had reached a point where it was overused. It changed what was possible for popular music, which led to a negative reaction that soon became known as punk. Even as tastes changed over time, the influence of this period continued. Progressive rock showed that popular music could be deep and grand without losing its emotional power, even if it was sometimes hard to achieve this balance.

Led Zeppelin, Sabbath, and the Birth of Heavy

In the 1970s, rock music went in two different directions. On one side, progressive rock became more intellectual. On the other side, another type of rock music became more physical. In the early days of hard rock and heavy metal, the focus was on creating music that was loud, heavy, and full of energy. The music didn’t require listeners to understand hidden meanings or follow complex stories. It tried to be felt as well as heard. During a time of social and economic problems, people found a way to express their feelings physically.

Bands like Led Zeppelin were inspired by the blues, but they played it at such a loud volume that it felt overwhelming. Their music was full of energy and feeling. It also had a mystical quality, often using images from mythology and going on long improvisation sessions. Albums like Led Zeppelin IV had songs that were easy to hear on the radio and other songs that were longer and more experimental. It showed that you could have songs that were heavy and ambitious at the same time. They changed what people thought a rock band could sound like and how popular they could become.

Led Zeppelin combined strong musicianship with an enigmatic aura. Deep Purple, on the other hand, focused on technical precision and energetic intensity. Their work showed off their musical talent, especially in the long guitar and organ solos that became a big part of who they were as a band. The song “Smoke on the Water” used technical skill in a way that was easy to recognize. It showed that a song could be heavy and memorable at the same time. The band’s style helped create the hard rock genre, which valued both intensity and musical skill.

The darker side of this movement was greatly influenced by Black Sabbath. Their early albums used horror imagery and showed some of the bad things in society. It made people feel scared, which was new for popular music. The slow, tuneless guitar parts and scary lyrics show the band’s worries about war, the decline of industry, and personal problems. Black Sabbath’s music made listeners feel uneasy. They created a new style of music called heavy metal. The style was about fear and feeling disconnected from society. It was also about power.

In the 1970s, critics often said that hard rock and metal music was too rough or extreme. But audiences embraced them for their direct impact. The music created a space where aggression and vulnerability could exist together. That was expressed through distortion, repetition, and high volume. Concerts became experiences shared by the community. They were defined by physical togetherness rather than subtlety.

In turn, this type of rock music made popular music more emotional. It did so by showing that intense music can also have a deep meaning. It expressed frustration, anger, and restlessness in a way that was easy to feel. The approach created a tradition that still influences heavy music today. That tradition believes that sound can express as much as words can.

Glam Rock: Bowie and the Theatrical Revolution

Hard rock is all about physical force, while glam rock is about transformation. Glam first appeared in the early 1970s. It treated identity as something that could change, that was created, and that was performed. Sound was important, but so were image, gesture, and attitude. The glitter, makeup, and staging didn’t distract from the music. They were a part of what it meant. Glam rock was different from other types of rock music because it didn’t have to look natural or masculine.

No artist showed this approach more clearly than David Bowie. Bowie’s characters, like Ziggy Stardust, were more interesting than his real self. Albums like The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars mixed fact and fiction. They used a theatrical approach to explore ideas about feeling disconnected from society, becoming famous, and human desire. Bowie’s work showed that being honest doesn’t mean being completely open and transparent. It could also be constructed through performance.

Alongside Bowie, Marc Bolan and his band T. Rex helped define glam’s melodic core. Bolan’s songs were short, had a strong rhythm, and were based on pop music, but they were presented in a way that was meant to be over the top. The mix of simple designs and bold styles made glam available to everyone while also challenging traditional standards. It introduced rock to a younger audience at a time when other types of rock were becoming more complex.

Bands like Roxy Music took glam to a more avant-garde level. Their music mixed rock instruments with experimental textures and a sense of irony. Images and sounds could be changed in the same way, which made people think that modern identity was influenced by the media, fashion, and performance. The approach was very popular in the UK. There, people were thinking a lot about class, tradition, and change.

Glam rock was often misunderstood, especially by critics who thought that being serious meant being restrained. It was difficult because it went against traditional ideas about gender roles and embraced ambiguity. That had long-lasting cultural effects. Glam made popular music more emotional and social. It did this by showing that an artist’s identity could be expressed through their music. It meant that an artist’s identity could be changed, questioned, and worn. It allowed for people to express their sexuality and individuality in ways that were not usually accepted.

In the 1970s, glam rock was a symbol that expansion meant more than longer songs or louder amplifiers. It meant that more people could perform on a rock stage and that they could do so in different ways. A push for more open identity and expression felt just as strong in the soul, where personal truth and political reality were becoming the same thing.

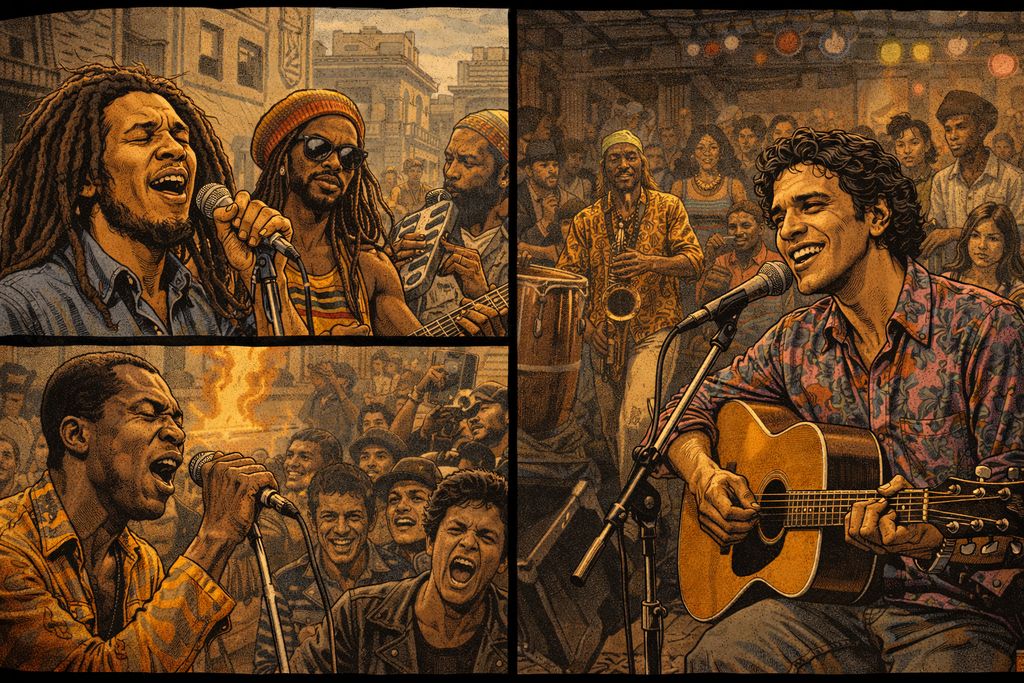

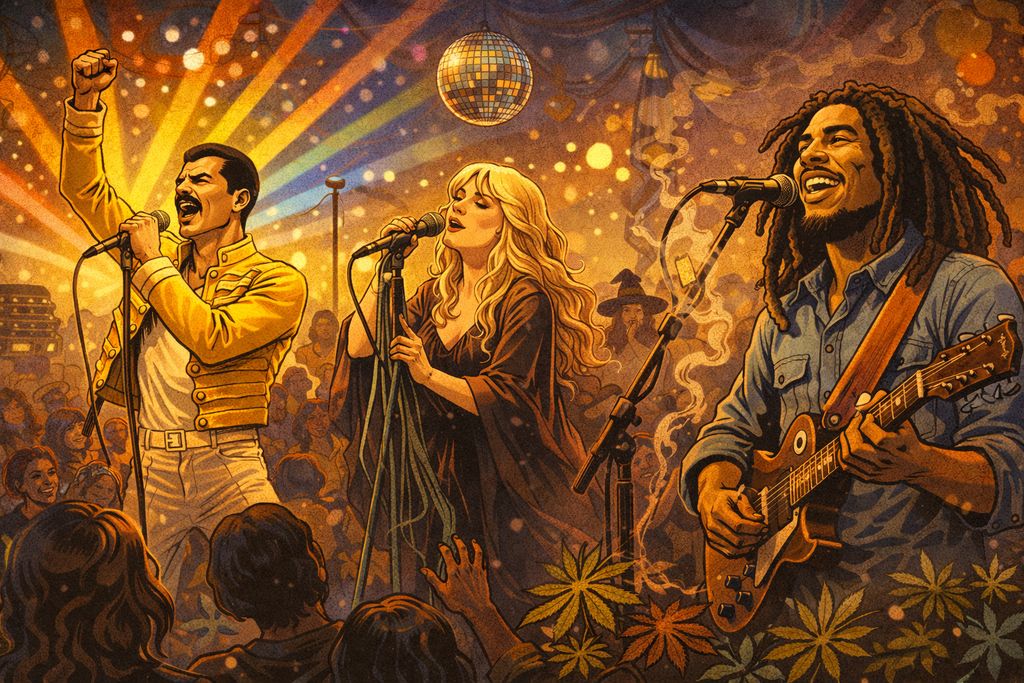

Soul Evolves: From Heartbreak to Revolution

Soul music entered the 1970s with a strong tradition and growing impatience. The genre had always been linked to the expression of ideas shared by a group, strong feelings based on religion, and the possibility of dignity through sound. By the late 1960s, that promise felt difficult to keep. Civil rights victories had not brought economic equality, and public optimism had given way to exhaustion and anger. Many Black artists felt that they could no longer sing only about love and celebration in a way that felt honest.

What came next wasn’t a denial of Soul’s past, but rather an expansion of its purpose. Artists started to see albums as places where they could think about their work and the world around them. They also used them as a way to express their ideas and define who they are as artists. Personal experience and political awareness were no longer separate issues. They informed each other. Songs talked about war, poverty, faith, intimacy, and doubt. These topics were often included in the same record. The soul’s emotional range widened. It became quieter in some places and more confrontational in others.

It also affected who had authority. Performers wanted to have more control over their music and the ideas it expresses. In the most artist-driven projects, producers, arrangers, and musicians worked together instead of supervising the project. The soul music of the 1970s is a diverse genre. It argues, asks questions, and thinks deeply. This captures a time when personal truth and political reality were connected, and music became a way of holding both together. That led to a larger effort to give Black artists more control over their work.

Marvin Gaye, Curtis Mayfield, and the Concept Album

In the early 1970s, several Black artists started to challenge the limits of soul and R&B music. For years, many performers worked in systems where they were closely managed. Singles were prioritized, messages were frequently edited, and creative decisions were reviewed by executives. At the start of the decade, things began to change. Artists wanted to be heard and to decide how they would express themselves. The album was the way they expressed that change.

There are very few records that symbolize this moment more clearly than What’s Going On by Marvin Gaye. The album was released in 1971 and was very different from Motown’s usual style. Instead of a bunch of possible hits, it’s a continuous thought about war, environmental damage, spiritual searching, and everyday struggles. Gaye’s voice is both gentle and intense, and it doesn’t offer a simple solution. At first, the label wasn’t sure about the project. They weren’t sure if people would like a work that was so clearly political and reflective. The album’s success showed that listeners were eager for such in-depth content.

A similar idea about artistic control influenced the work of Curtis Mayfield. His music for the movie Super Fly is one of the most complex cultural documents of the decade. People often criticized the film for making crime seem attractive, but Mayfield’s music offered a more complex view. The songs talk about big problems in society and how people are tricked into thinking they’ll make a lot of money quickly, but it’s not true. They do this in a way that’s easy to listen to, but the message is still shocking. Mayfield showed that socially engaged music could be both sophisticated and meaningful.

These albums show a bigger change in how Black artists thought about their role. Concept albums let them tell complex stories that showed contradictions instead of making their music simpler just to reach the broadest audience. One body of work contained a mix of different feelings and emotions, including faith, frustration, pride, exhaustion, hope, and skepticism. That complexity was closer to real life than the hopeful singles of earlier years.

The shift toward artistic control wasn’t just about lyrics. It also affected the production choices, the order of the steps, and how things looked. Artists wanted to be able to create entire projects, not just individual songs. That struggle was uneven and often met with resistance, but it had a lasting impact.

In the early 1970s, Black artists used their albums to think deeply about themselves and define who they were. It changed what people expected from soul music. They showed that you could have commercial success and critical acclaim at the same time. That made popular music more culturally important. It made records feel more like conversations than things you could buy.

Aretha, Roberta, and Minnie: Soul's Leading Ladies

The growth of soul music in the 1970s was greatly influenced by women singers who had strong voices and could express a lot of emotion. However, their job security was still uncertain. While male artists started to take charge of their albums and the stories they told, women often had to balance being expressive with keeping a careful image. People were happy about their success, but only to a certain extent. That was rarely the case for men.

Aretha Franklin was already a famous soul singer when the decade began. In the 1970s, her work became more introspective, reflecting changes in her personal life and the cultural context around her. Albums like Young, Gifted, and Black and Amazing Grace showed a wide range. They moved easily between being political, spiritual, and personal. Franklin’s authority didn’t come from making big changes, but from strengthening the connection between voice and meaning. Even so, her career shows how women were often expected to be strong and reliable, even though they faced the same uncertainties as their peers.

Roberta Flack offered a different way of being present. Her simple, understated delivery and careful arrangements allowed for small, subtle emotional changes. Songs like “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face” and “Killing Me Softly with His Song” are more intense when they’re played softly. Flack’s success made people question what it takes to be successful in the music industry. But when people discussed her work, they often misunderstood her subtlety. They thought she was passive, when in fact she chose to be subtle on purpose as part of her art.

The tension between being visible and being vulnerable is especially clear in Minnie Riperton’s work. People know Riperton for her amazing vocal range. But even though her albums like Perfect Angel are full of emotional warmth and show a lot of care in their composition, some people still see her as a technical curiosity. Her music was a mix of joy, intimacy, and optimism, but the industry often struggled to see her as more than just a new trend. Her early death shows that many careers were still very fragile, even if the person was talented or well-known.

These artists are connected by their ability to interact with expectations in a variety of ways. Women were allowed to be emotionally open, but they were often not allowed to control the story. Their personal lives were examined closely, their careers were more easily interrupted, and their authority was questioned more often. Even when their records sold well, they couldn’t be sure that they would last.

Despite these challenges, their impact was significant. Women in Soul made the genre more expressive by focusing on emotional truth, strong voices, and artistic dignity. They showed that strength can be subtle, vulnerability can be intentional, and authority doesn’t need to imitate existing models. Their work created the foundation for later generations, but it also showed that there was still a lot of work to be done.

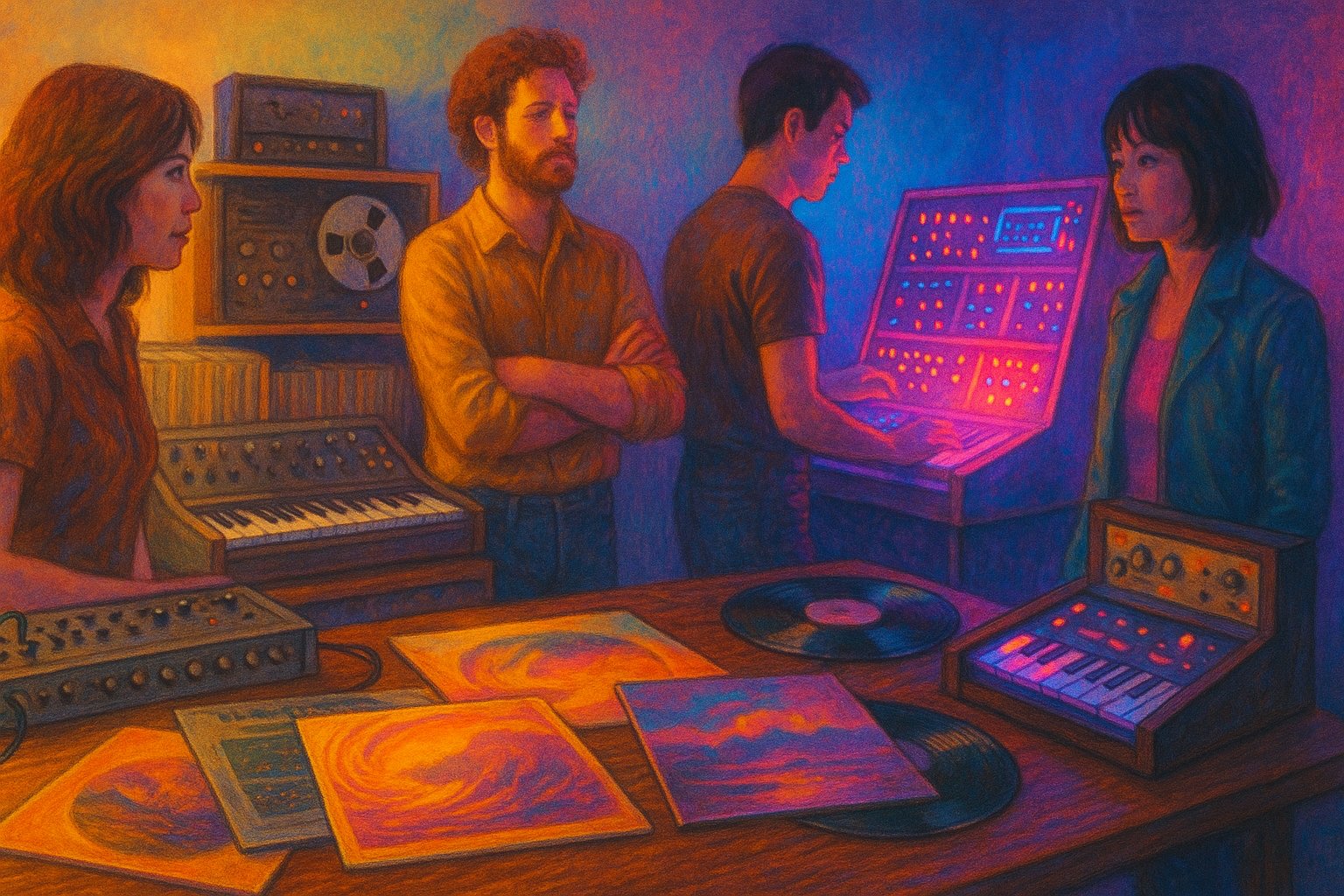

Quincy Jones, Gamble & Huff: The Sound Builders

As soul music became more ambitious in the 1970s, the people who created it became more important to its identity. Producers and arrangers were no longer just there to make things technical. They helped artists turn their ideas into albums by acting as translators between artistic vision and recorded reality. These collaborations were most effective when they allowed for more creativity. When they were at their worst, they made the existing hierarchies stronger. The difference was often about trust and power.

Quincy Jones is a strong example of producer-driven influence. During that decade, his work focused on clarity, balance, and emotional precision. Jones knew how to make a voice sound good, how to make the music support the voice instead of overwhelming it, and how to bring together musicians without making them all sound the same. He thought of production as a way of showing the artist’s ideas. Finding that balance was rare, and it mattered.

A unique style of music came about in Philadelphia thanks to the work of Kenneth Gamble and Leon Huff. Their music mixed rich orchestration with rhythmic precision, creating a polished sound that still felt urgent. The Philadelphia soul style brought together two different types of music: socially conscious songwriting and danceable rhythms. The style influenced both mainstream pop and the emerging disco movement. In this case, the arrangement was not the decoration. It had meaning, and it showed confidence, elegance, and control.

People like Thom Bell were important in creating this style. Bell’s use of string instruments added emotional depth and narrative flow to the songs, transforming them into immersive environments rather than mere statements. These choices influenced how listeners understood intimacy and scale in soul music. The album’s design made listeners want to listen to the whole album from start to finish instead of switching between songs.

Session musicians helped create the sound of that decade. They often don’t get credit or aren’t recognized enough. They helped keep things consistent between different artists and record labels. Their playing created textures that were easy to recognize. These textures linked otherwise distinct records. Such hidden labor makes it hard to know who wrote a particular work. While artists fought for control, their ideas were often made real through the work of many people.

Producers and arrangers became more important. That raised important questions about authority. Who really influenced the music? Who was seen, and who remained invisible? The most successful collaborations were ones in which power was shared, and the results felt expansive. In other cases, people shared their creative ideas in one direction, which made existing inequalities stronger.

To understand the sound of 1970s soul, you have to listen for more than just voices. You have to listen for decisions. The way things are set up—how fast or slow, rough or smooth, and how much space there is—can show if people are working together, discussing, or taking charge. These records last not just because of the songs, but also because of how the singers’ voices fit perfectly with the music, setting the stage for funk’s rhythm-first language.

Funk: When the Beat Became the Message

In the early 1970s, soul music often focused on personal feelings. Funk, on the other hand, was more about dancing and moving your body. It was music built on repetition, rhythm, and the performer’s physical presence. Funk didn’t ask listeners to think about or consider an argument before responding. It demanded movement. It was a different kind of seriousness. It was based on shared experiences instead of personal stories.

Funk came from soul, but it removed many of its smoother surfaces. Harmony paused for a moment. Rhythm became more important. Bass, drums, and tightly locked grooves became the focus. The change was more than just a musical preference. It expressed a desire for grounding at a time when social and political structures felt unstable. The groove became something reliable. It became something you could return to when words felt insufficient.

At its core, funk was communal music. In the past, bands worked together as a unit, not as vehicles for a single star, even when they had a charismatic leader at the front. The performers and audience members were so focused on the music together that they felt like they were all part of the same group. Funk records and concerts felt less like public declarations and more like get-togethers.

In the 1970s, funk was also a big part of culture. It showed that they were proud, that they were present, and that they would continue to be there even though there was still inequality. It showed its strength by working together and staying strong, without using specific slogans. To understand funk, you have to know that rhythm can be a way for people to identify with each other. It creates a bond between people by giving them something in common: time, movement, and sound.

James Brown: The Man Who Changed Rhythm Forever

Funk didn’t start in the 1970s, but it was during that decade that it became its own language. At the heart of that change was James Brown. By 1970, Brown had already changed many of the rules of soul and rhythm and blues music. He created a new musical style that was based on repetition, precision, and a constant focus on rhythm. Melody became less important. Harmony was reduced to sharp accents. Everything was in sync with the rhythm.

Brown’s impact in the early 1970s was much bigger than just his own music. He thought of the instrument as a part of the rhythm. The bass wasn’t just a part of the harmony; it played an important role in it. It was the driving force behind the song. Guitars were used as percussion instruments, using rhythm instead of space. Instead of carrying melodies, horns punctuated the music. The structure required total discipline from the musicians, and it created a sound that felt both tight and explosive. In this sense, funk was not improvised. It was a controlled intensity.

The approach became important because it focused on timing. Funk told everyone to pay attention to each other. One person’s talent was less important than the ability to get the group to play together. The focus was in line with larger ideas of Black communities working together, where the strength of the group was often more important than the recognition of individuals. In Brown’s bands, leadership was clear, but the members worked together to carry out the plan. The groove only worked if everyone did their part.

A focus on rhythm also changed how audiences engaged with music. Funk wasn’t made for just sitting there and listening. It was physical, immediate, and everyone took part. Live performances became spaces where people moved together, and the back-and-forth of the music went beyond just the singing. The audience didn’t just watch. It joined in by moving. In that sense, funk mixed together the performance and the experience.

Beyond its immediate impact, funk’s rhythmic style proved to be very lasting. Brown’s focus on the first beat of the measure became very important for later types of music. Hip-hop producers would use parts of these songs as the base for their own tracks. They saw funk not as something to be remembered, but as a source of inspiration. The clarity and repetition that were once seen as weaknesses became strengths in new situations.

In the 1970s, funk music showed that rhythm can have its own meaning. It didn’t need complicated stories or images to show who it was and its power. Funk music was a way for people to express themselves through their movements and the time they spent together. It reminded listeners that music can be experienced together, in the moment, through the movements of bodies following the same beat.

Parliament-Funkadelic: George Clinton's Universe

If James Brown defined the grammar of funk, George Clinton expanded its imagination. Clinton is famous for two projects: Parliament and Funkadelic. Together, these projects turned funk into a big, complex world that mixed humor, science fiction, and ideas about society. Parliament-Funkadelic was very different from earlier funk music. Earlier funk focused on discipline and being a tight unit. But Parliament-Funkadelic leaned into going over the top, being funny, and making people confused. The result was not chaos. It was a different kind of order. That order challenged traditional ideas of respectability and seriousness.

Albums like Mothership Connection and One Nation Under a Groove created a shared mythology. The mythology invited listeners to enter an alternate reality. The world seemed playful and absurd on the surface, but its purpose was clear. Clinton rejected the idea that Black identity was only about struggle. Instead, he used fantasy and exaggeration to show that Black identity could also be about other things. Funk became a place for joy, imagination, and reinvention. The elements of the play were not distractions. They were tools for expanding what freedom could look like.

Parliament-Funkadelic built on the rhythmic foundation of earlier funk music, but they added dense textures and unpredictable arrangements to it. The presence of multiple singers, synthesizers, and long jams created a feeling of abundance instead of restraint. The group’s identity was closely tied to its collective nature. People joined and left, used different names, and had overlapping roles. The people behind the music were not clearly identified, which made it seem like the music was created by the community instead of just one person, even though Clinton’s influence was clear.

Live performances made this idea stronger. The Mothership’s famous arrival on stage made concerts into events where everyone took part. The audience wasn’t supposed to be impressed by how well the performance was executed. They were invited to participate in an event that combined rhythm, humor, and a spectacular performance. The approach was very different from the increasingly formalized presentation of arena rock. It offered an alternative idea of what a large-scale performance could be.

Parliament-Funkadelic is important in culture because it doesn’t separate having fun from having meaning. The group showed that political and social commentary doesn’t have to be serious to be effective. They did this by mixing music with storytelling. Black music was a way to fight against the idea that it should either educate or entertain people, but not both. It did this by being funny, wild, and fun.

That approach had a big impact that lasted well beyond the 1970s. Later on, hip-hop artists got a lot of their sound and style from Parliament-Funkadelic. They didn’t just borrow their music, but also their attitude. The idea that music could create its own worlds instead of simply describing reality became a lasting legacy. In the 1970s, Parliament-Funkadelic showed that funk could be more than just rhythm. It became a way to imagine being free and making your own rules.

Funk's Legacy: From Disco to Hip-Hop

By the mid-1970s, funk had become more than just a genre. It became the foundation. Its influence spread beyond the artists who defined it. It helped to change how rhythm, repetition, and collective energy were understood across popular music. Many styles of music have a clear high point and a clear low point. Funk was different in that it could change and adapt. Its main ideas were simple enough to travel, but strong enough to still mean something in new situations.

One reason for this is that Funk focuses more on structure than on surface details. The focus on low, steady rhythms, repeating parts, and strict timing created music that could be taken apart and put back together. As recording technology improved, these elements became the best possible source material. People didn’t just listen to funk records; they danced to them. They were studied, reused, and transformed. That process started quietly in the 1970s, long before it became an important part of hip-hop culture.

Artists and producers in new music scenes saw the possibilities of funk as a tool. The music of James Brown and Parliament-Funkadelic offered rhythmic clarity that made way for new styles of music. Funk’s use of repetition and its openness to long sections made it a great candidate for reinterpretation. It asked people to take part instead of just looking at it.

Beyond hip-hop, funk influenced disco, dance music, and later electronic genres. Its focus on movement and physical response spread directly to club culture. Even as the tempos changed and the instruments were different, the main idea stayed the same. Music could help people stay in time. It could bring the community together by getting everyone to move at the same time. Funk taught other types of music how to focus on that experience without using lyrics.

Another important aspect of funk’s approach was its emphasis on collective learning. In the band, there was a group dynamic, not a one-person show. The approach went against the commonly held beliefs about who can be a writer and what it means to be successful. It wasn’t always fair in practice, but it offered a different approach from the usual “genius” model that was common in other parts of the industry. That idea would be very popular with later movements that focused on crews, scenes, and shared identity.

Looking back, funk’s impact is less about a particular sound and more about a way of thinking. The idea was that music could be created from the beginning, starting with rhythm and then adding other elements. It suggested that joy, repetition, and physical engagement are not distractions from meaning; they are actually pathways to it. As the 1970s were ending, funk music had already started to influence the future. The grooves of this music have lasted and continue to be a part of popular music today. They promoted a philosophy of presence and connection, which helped create the culture of disco.

Disco: The Revolution on the Dance Floor

People often remember disco through exaggerated stereotypes. Shimmering dance floors, over-the-top fashion, and a sense of excess that later made it an easy target for ridicule. But this surface image doesn’t show the real reasons why disco mattered, and why it became popular at that time. Disco wasn’t about big shows. It was about space. It created places where people who were often excluded in other places could gather, move around, and be seen in their own way.

Disco music started in certain communities. It was influenced by Black, Latino, and LGBTQ+ experiences in cities. It was more like a club than a concert hall, with DJs instead of bands, and longer songs instead of the usual ones. The music was more about keeping the same beat and rhythm than about having a big, exciting climax. That allowed dancers to focus on moving freely and smoothly. It was not just something to pass the time. It provided collective release.

As disco moved from underground clubs into mainstream culture, its meaning changed. Its success made it more visible, but also led to misunderstanding and negative reactions. What started as a culture of inclusion was seen as superficial or fake. The hostility that followed showed that people were worried about things that had nothing to do with music.

To understand disco in the 1970s, you have to look past how it was portrayed and listen closely to its purpose. Disco was not a brief detour in popular music. It was a response to the challenges of the real world. It used music, technology, and a sense of community to create a place where people could feel connected, even though many other places did not offer that.

From Clubs to Charts: Disco's Roots

Disco was not a commercial genre from the start, and it didn’t have famous stars. It started out in clubs where people didn’t go to watch the performers. Instead, they went to create a certain atmosphere. These spaces were often created by communities that didn’t have much visibility. Black, Latino, and LGBTQ+ people met in clubs not just to dance, but to feel free and be themselves. Music was the key that made that possible.

Disco culture was different from rock concerts. At rock concerts, people looked at the stage. But at disco, people looked at the dance floor. The DJ, who was hidden or at the edge of the room, was in charge of how the night felt. Instead of playing songs on their own, DJs played records one after the other, creating a continuous flow. Longer mixes let dancers keep the same rhythm for a long time. The goal was to create an immersive experience, not to have a climactic ending.

David Mancuso was one of the most important people in creating this approach. His Loft parties in New York focused on three things: good sound quality, trust, and a shared experience. There was no dress code, no advertising, and no pressure to perform. The music played smoothly, switching between soul, funk, and early disco styles. It was based on the crowd’s response rather than on what was expected to sell. The model prioritized the club’s social atmosphere over its business aspects.

Larry Levan had a similar philosophy. His later work at the Paradise Garage became legendary. Levan understood the DJ’s role as a source of emotional support. The music’s speed, feel, and length were changed right away to match the crowd’s energy. In this case, records were tools, not final statements. Their value was in how they functioned together in a shared moment.

Disco was heavily influenced by funk and soul music, but it was also a way to get people to dance for longer. The bass lines became steady and insistent. The drummer was playing in a steady, predictable way. The addition of orchestration made the piece shine without disrupting its flow. When there were vocals, they often added texture instead of focusing on the narrative. The structure allowed music to go beyond the formats used on the radio.

It’s important to understand where disco came from. Before it was branded, marketed, or dismissed, disco was a way for people to come together. It made people feel safe and like they belonged. That feeling came from rhythm and repetition. When disco became popular, much of this context was lost. The negative reactions that followed are related to that loss. Disco music reminds us of the places where it started. Those places were important because the people who lived there were important too.

Bee Gees, Chic, and the Mainstream Explosion

Disco started as something that was only popular among a small group of people. Then, it became popular worldwide. That change did not happen by accident. The development of studio technology, the growing influence of producers, and the industry’s desire to appeal to a wider audience all contributed to the rise of club culture. What started in dark rooms spread to radio, film, and arenas, changing popular music.

Producers played a key role in this change. Giorgio Moroder was one of the most influential figures in music. His work changed what disco could sound like. Moroder made disco music sound more futuristic by combining electronic instruments and precise mechanical rhythms. That was different from soul and funk styles. He worked with Donna Summer on songs like “I Feel Love,” which used texture and repetition in a new way that was different from traditional song structures. The result felt both personal and grand, like electronic dance music even before it had a name.

Meanwhile, groups like Chic made the music more elegant and clear. The band Chic was led by songwriter and producer Nile Rodgers and bassist Bernard Edwards. They combined the energy of funk music with the popularity of pop music. Songs like “Le Freak” and “Good Times” were carefully put together, mixing sophistication with immediate physical appeal. Their success showed that disco could be mainstream while keeping its rhythmic identity.

Disco’s popularity spread around the world, helped by bands like the Bee Gees. Their songs on the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack made disco more popular than ever before. The movie showed disco as a cultural moment, linking music, fashion, and dance together in a single story. The exposure made disco popular with millions of new listeners. However, it also made the image of disco too simple and uniform. The focus was on the spectacle, not the context.

As disco spread around the world, local scenes added their own traditions to it. European producers started using synthesizers and precision, while other regions focused on orchestration or percussion. The genre was flexible enough to include these variations, and it became a shared language with regional accents.

It was a peak moment for disco, but also a turning point for the genre. The music became very popular, but it lost its connection to the communities that had created it. To understand disco’s global phase, you have to recognize both its creative achievements and the compromises that came with its rise.

Disco Demolition: When Success Brought Hate

By the late 1970s, disco was everywhere. What started as a culture that was only in certain communities was now everywhere. You could hear it on the radio and see it on television. That caused a reaction that went beyond musical taste. The public’s negative reaction to disco was portrayed as a response to its commercialism. However, there was more to it. People and spaces associated with disco were also a source of discomfort.

Rock audiences and critics started to see disco as unnatural, repetitive, and not taken seriously. These criticisms often missed the point. Disco wasn’t designed to be like rock music. It focused more on maintaining the flow of the story than on creating a dramatic peak, and on sharing the experience with the group rather than on the expression of the individual. Using rock’s standards to judge it led to misunderstanding. But those standards were the main focus of most discussions, which led to the way the genre was talked about and dismissed.

The most obvious sign of this hostility was the Disco Demolition Night event in 1979. It was promoted as a way to symbolically end the disco genre. Although it was presented as a playful rebellious act, the images and language used in its promotion revealed something more concerning. The anger directed at disco often had racial, gendered, and homophobic undertones. The genre is closely associated with Black, Latino, and LGBTQ+ communities. That made it an easy target in a cultural climate that was already resistant to social change.

Artists caught in the middle of this shift experienced mixed results. Musicians like Donna Summer, whose work had been greatly influenced by new studio techniques and personal expression, suddenly found their music being treated as if it were disposable. Some musicians tried to move away from the disco label, even though their music still had a lot of disco influences. The negative reaction did not completely remove disco’s impact, but it did reduce the amount of space where it could be accepted openly.

Despite this, disco never really disappeared. Its techniques slowly started to be used in other ways. Dance music, pop production, and new electronic styles influenced its focus on rhythm, texture, and long-lasting sounds. Even as disco fell out of fashion, DJs kept building nights around continuity and flow. The culture changed, but it didn’t collapse.

In hindsight, the strong negative reaction to disco music shows how limited acceptance of different types of music was in 1970s popular culture, rather than reflecting the true qualities of the music itself. Disco changed people’s ideas about who music was for and how it should be experienced. Resistance grew as that became clear. But the strength of that reaction shows how important disco is. It showed that there were problems with who people thought they were, what they enjoyed, and whether they felt like they belonged. Music alone didn’t cause these problems, but it made it impossible to hide them.

Disco’s story in the 1970s is not about going from success to failure. It’s about moving from one place to another. It was moved out of the spotlight, but it still had an impact. It helped shape the sound of what came next, and it carried its values forward under different names. As disco was becoming more popular, a different kind of resistance was forming: punk.

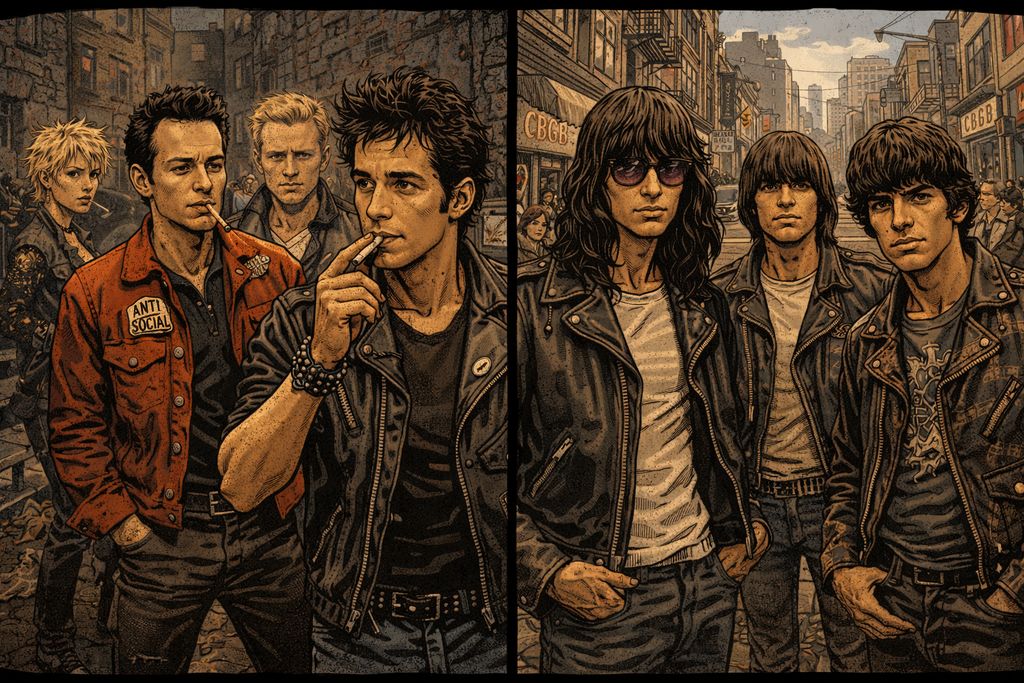

Punk: Burn It Down, Start Again

By the mid-1970s, many young listeners felt like popular music and everyday reality were worlds apart. Arena rock had become too big and expensive. Progressive rock had become too abstract. And disco, at least in its mainstream form, felt too polished and had lost its original style. Punk came about as a direct reaction to a feeling of being left out. It wasn’t a move that was meticulously organized; it was more of a spontaneous response. It was music made by people who didn’t see themselves on the big stages of the decade.

Punk rejected technical skill, elaborate production, and the idea that music needed permission or prestige. Its power was in how immediate it was. Short songs, simple structures, and raw performances replaced long solos and ambitious concepts. It was not a return to innocence; it was a refusal of hierarchy. Punk said that anyone could pick up a guitar and speak their mind, even if what they had to say was messy, angry, or unresolved.

The social conditions that shaped punk were especially strong in the United Kingdom. There, economic decline and many young people being out of work created a frustrating and unchanging situation. In the United States, punk reflected a different kind of alienation. In the U.S., that alienation was connected to urban decline and a general feeling of cultural fatigue. Even though there were differences, punk scenes on both sides of the Atlantic had one thing in common. They took rock music and removed all the extra parts. They used it to create confrontation instead of escape.

Punk didn’t try to replace the most popular music of the 1970s. It tried to show what they could no longer express.

The Conditions That Created Punk

Punk didn’t appear because rock music had become too complicated. Many young people felt like the world was closed off to them. In the mid-1970s, the United Kingdom was experiencing economic decline. Factories closed, many people lost their jobs, and entire neighborhoods didn’t have much hope for the future. The promise that effort would be rewarded no longer felt true. For a generation of people who grew up in this environment, the optimism found in earlier rock traditions didn’t seem realistic.

Music that celebrated skill, money, or freedom felt far removed from daily life. Punk formed in opposition to that gap. It said that cultural value doesn’t have to be earned through training, refinement, or approval from an institution. The message was clear and direct. You don’t need permission to speak. You don’t have to sound perfect. The most important things were being urgent and honest, even when it was hard to be honest.

The attitude became most obvious with bands like the Sex Pistols. The band’s confrontational style reflected the anger and boredom of their audience. Their songs were short, direct, and clearly against authority. Their lyrics rejected performances of national pride, social mobility, and political leadership. The band’s image was often made to seem more exciting than it really was. But they had a big impact because they showed exactly how frustrated their listeners were. Punk did not offer any solutions. It was a clear “no.”

Meanwhile, punk was influenced by material limitations. Inexpensive instruments, small venues, and limited access to studios led to a kind of creative minimalism. These limits weren’t seen as a bad thing; they became a part of the design. Simplicity was not a lack of ambition. It showed who the music belonged to. Punk scenes formed around local places, informal networks, and shared discontent. They didn’t form around professional infrastructure.

In the United States, punk developed in different situations but with similar emotional pressures. Problems like urban decay, cultural stagnation, and a sense of being left out of mainstream culture led to scenes in cities like New York. Bands like Ramones made rock music as simple as possible. They focused on playing fast and repeating the same musical phrases over and over again. Their songs didn’t talk about politics directly, but their refusal to indulge in excess conveyed its own criticism.

Punk happened because many people stopped believing that the systems around them were listening to them. Punk rejected sophistication and embraced immediacy. That created a space where frustration could be expressed directly. It changed limitations into an identity, and this changed the meaning of being involved in popular music.

UK vs. US: Two Scenes, One Attitude

Although punk music was similar in the United Kingdom and the United States, the punk scenes in these countries developed with distinct priorities and styles. They were similar in their attitude, not in their circumstances. Punk was not a single style that moved in one direction. It was a series of local reactions to different types of cultural fatigue.

In the UK, punk was openly against the establishment, authority, and national identity. Bands like Sex Pistols and The Clash didn’t just critique society. They faced it head-on. The Pistols’ performances were intentionally harsh. They were meant to cause outrage, not understanding. Their music sounded like collapse. It was short bursts of noise and contempt. It made them feel like they were shut out of the future. The Clash was a punk band that was as urgent as any other punk band, but they did something else that was unique. They used their music to talk about important issues like politics, race, and what was going on in the world. Their songs connected local problems to larger, more widespread systems of power. It showed that punk could be both confrontational and outward-looking.

In the United States, punk developed in a more diverse cultural environment. The economy was down and cities were falling apart, but people experienced these changes in different ways. New York’s early punk scene was focused on small places for shows, not on making a big national statement. Bands like Ramones made rock music faster, played the same few songs over and over, and used simple melodies. Their songs didn’t talk about politics. Instead, they expressed alienation through minimalism and humor. The refusal of complexity was the statement.

Patti Smith was another important figure in the American music scene. Her work combined the raw energy of punk with a literary style. Her performances mixed spoken word, rock energy, and personal storytelling. Smith’s presence made people think differently about who punk was for and what it could include. She made a space full of aggression more emotional and less aggressive by bringing introspection and vulnerability to it.

These differences show how punk can change to fit in different situations. In the UK, punk often sounded like a public argument. In the US, it felt more like a private refusal. Both approaches rejected the idea that music had to be perfect or make people want to be better. The most important things were being there and being direct.

Even though there were differences, the punk scenes in the UK and the US were based on the same idea. Music should reflect real life, not make-believe. By keeping their music connected to the local environment, these bands made sure that punk didn’t become a style that was disconnected from its background. It was a practice that was based on location, frustration, and the desire to be heard without the need for mediation.

DIY Forever: Punk's Real Revolution

One of the most lasting contributions of punk music to the culture of music was not its sound or its image, but the systems it built. Although it was easy to imitate the visual style of punk, its most significant impact came from how it changed the way music could be created, shared, and supported outside of traditional industry structures. Punk treated infrastructure as part of the message. Independence was not just a slogan. It was a practice.

In the UK and the United States, punk scenes relied on small venues, informal networks, and local initiative. Musicians or their friends and fans often organized shows, instead of professional promoters. It allowed people to try new things and learn from their mistakes without facing severe consequences. The focus was on taking part, not on being perfect. If a band could play three chords and make people feel like they need to act now, it was a good band.

Independent record labels played an important role in this change. They worked with small amounts of money and weren’t too worried about what would happen. But they offered something that big record companies often couldn’t: trust and a sense of urgency. Releases can be made quickly, without needing approval from many people. That speed let punk react to its surroundings. The music reflected the present moment, showing frustration rather than reflecting on the past. In this sense, punk was like a local news source. It documented the moods and tensions of the times.

Printed media was also very important. Zines, flyers, and small-run publications shared ideas with music, creating a shared language across different groups. These materials were often basic in design, but that simplicity reinforced the underlying philosophy. Communication doesn’t need to be perfect to be valid. All that mattered was being honest and being open. Punk culture valued being yourself more than looking cool.

The same infrastructure also changed how people thought about authorship and success. Punk bands usually didn’t think their careers would last for many years. Many people thought they would be around for a short time, be really intense, and then go away. This acceptance of impermanence reduced pressure and encouraged risk. It made space for constant renewal. The scene changed quickly as bands came together, broke up, and then came together again in new groups. The network was the focus, not the individual names.

The long-term impact of this system is significant. Punk was a type of music that was very DIY. It became the foundation for other types of music like alternative, indie, and underground. Even artists who weren’t part of the punk scene embraced its ideas about independence and small scale. People started to think that music could exist and be meaningful without being accepted by most people. It changed what people expected from music. While punk bands were rebuilding local music scenes in the West, equally important movements were happening in other parts of the world outside of the United States and Great Britain.

Punk treated infrastructure as part of artistic expression. That allowed punk’s values to survive beyond the lifespan of individual bands. It offered a repeatable model instead of a fixed style. That model, based on access, urgency, and self-organization, is still one of the most important legacies of 1970s music culture.

Global Voices: Music Crosses Every Border

In the 1970s, popular music was no longer just a conversation between the United States and the United Kingdom. While rock music from the United Kingdom and the United States was still the most popular in the world, other artists were making their own music that was different and new. In this decade, music from around the world became more important in Western music. It was no longer just a small part of the music; it was as important as other parts of the conversation.

Several forces drove this change: migration, political unrest, and growing recording and touring networks. Musicians brought local traditions to new places, mixing them with rock, soul, and funk in ways that were hard to put into a simple category. These hybrid forms were not meant to copy Western styles. They were acts of translation that were influenced by colonial histories, regional struggles, and distinct cultural priorities.

Many listeners in Europe and North America heard this music for the first time. It gave them new ways of thinking about the world. Songs addressed topics like dictatorship, exile, spirituality, and collective memory. They were often very direct, which was very different from the introspection that was typical of much Western rock music at the time. At the same time, these artists dealt with unequal power relationships. They often needed Western labels, festivals, and media to be recognized around the world.

The music of the 1970s shows us that popular music has always moved in many different directions at the same time. It tells the story of the decade in a new way, showing that innovation doesn’t just come from one place. It grows through interaction, opposition, and adjustment across different borders.

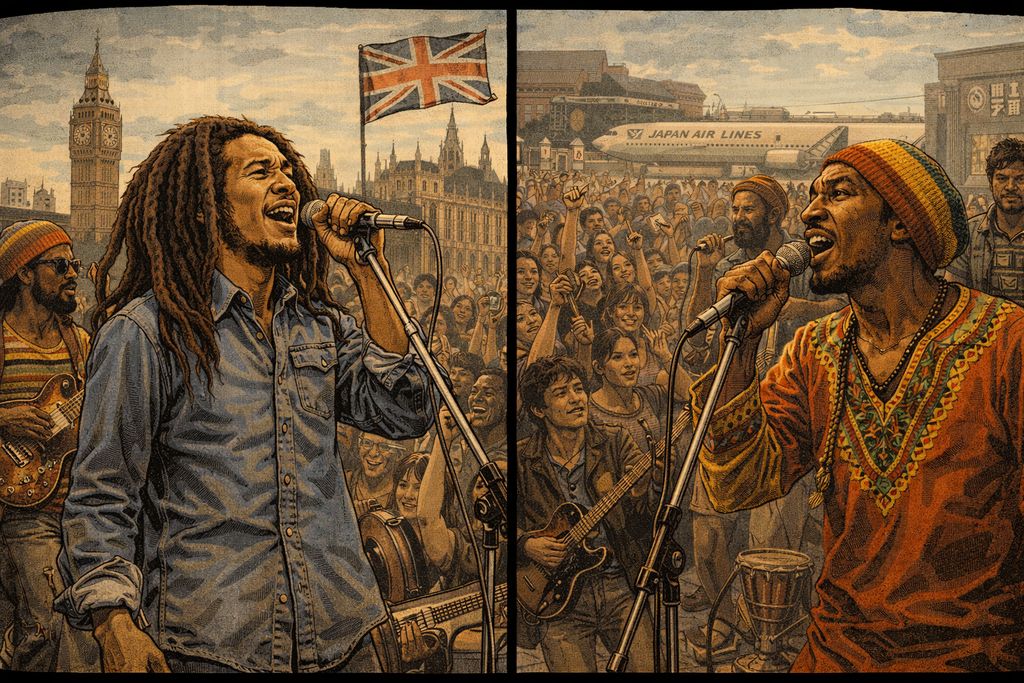

Bob Marley and the Rise of Reggae

Reggae music became much more popular around the world in the 1970s. That was an important change in how music from non-Western countries became well-known around the world. Reggae music is based on Jamaican history, spirituality, and social struggle. It often shares its message as part of its context. The music directly addressed issues such as poverty, oppression, exile, and faith. It often used plain language that didn’t use metaphors. It was powerful because it was clear, not vague.

The movement was led by Bob Marley, whose music with the Wailers made reggae popular with audiences all over the world, not just in the Caribbean. Albums like Catch a Fire and Exodus showed how local experiences can be understood on a global scale without losing their significance. Marley wrote songs that combined political urgency with spiritual beliefs, drawing heavily on Rastafarian beliefs. The songs talked about violence, displacement, and liberation. They also talked about not giving up.

Reggae is known for its connection to rhythm and the use of space. The focus on the unusual created a feeling of suspense, a steady push against what was expected. The bass lines were melodic and powerful, providing a solid foundation for the music while also creating space for listeners to think and reflect. That structure supported lyrics that were meant to be taken in slowly. It was meant to encourage listeners to really think about the message instead of just listening to it quickly. Reggae demanded attention, but not through being loud or complicated. It worked through repetition and weight.

Reggae’s popularity spread around the world as people moved from place to place. Jamaican communities in the UK were very important in creating music in new cultural settings. Sound systems became important places for social life. People listened to all kinds of music there, like reggae, punk, and soul. The music influenced local scenes in ways that people didn’t expect. The music resonated strongly with audiences facing their own forms of marginalization, even when their experiences were different.

Meanwhile, reggae’s global success revealed existing tensions. Western labels often used simple images to market this genre. They focused on surface symbols and ignored the deeper political context. Marley was careful to avoid the pressures of his fame. He used his visibility to speak out against the mainstream expectations for celebrities.

Reggae was important in the 1970s because it didn’t separate art from real life. It showed that popular music can be specific to a region and still be understood all over the world. Instead of adapting to the tastes of the world, reggae changed those tastes. It insisted that voices from the margins could define the conversation on their own terms.

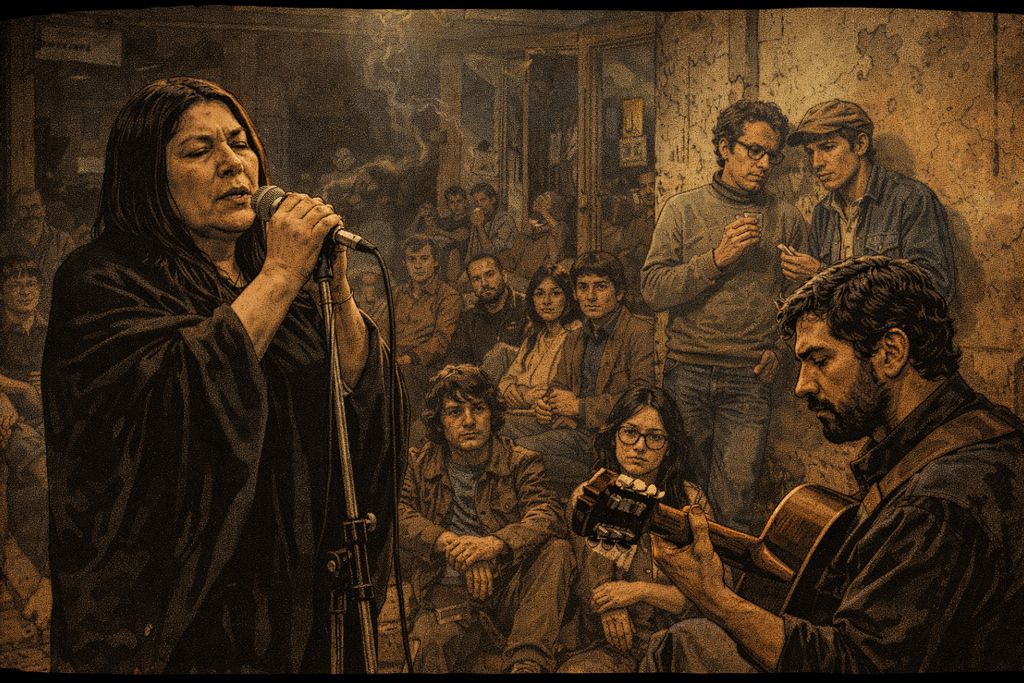

Fela Kuti, Santana: Political Grooves

Reggae brought the voice of Jamaica to the world. Other regions created new types of music that mixed local traditions with rock, funk, and jazz. These new types of music were also political. These styles did not come from trying to copy Western trends. They grew out of specific histories influenced by colonialism, dictatorship, and cultural displacement. Music became a way to speak about power when it was dangerous or not allowed to speak in other ways.