Why the 1980s Still Matter Today

The 1980s are often remembered for their bright colors, big hair, and popular songs that were played on repeat. The decade was not simple or harmless. Music changed the way it related to power, technology, and identity. These changes still affect how we listen to music today.

The 1980s did not start out as a new era. They grew out of the exhaustion and ambition of the 1970s. They took rock, soul, punk, disco, and reggae and changed the rules. The style changed, but the structure changed more. Music spread more quickly, was harder to avoid, and was more closely linked to images, markets, and global stories. Artists became more popular than ever before, but they lost some of the privacy and control that earlier generations of artists enjoyed.

Contradictions defined the decade. People had more creative freedom, but companies were also having more influence. New technologies lowered some barriers while raising others. Even though a few stars dominated the global conversation, many different groups were doing well in clubs, bedrooms, and local communities.

To understand 1980s music, you need to know more than just how it sounded. We need to understand what it demanded, what it offered, and what it quietly took away.

The Morning After: When the 70s Became the 80s

The change in style from the 1970s to the 1980s is often described as a big change. In reality, it was slower, messier, and more revealing. Many sounds that were characteristic of the early 1980s were already around before the calendar turned. The way music worked in culture and industry changed more than its sound.

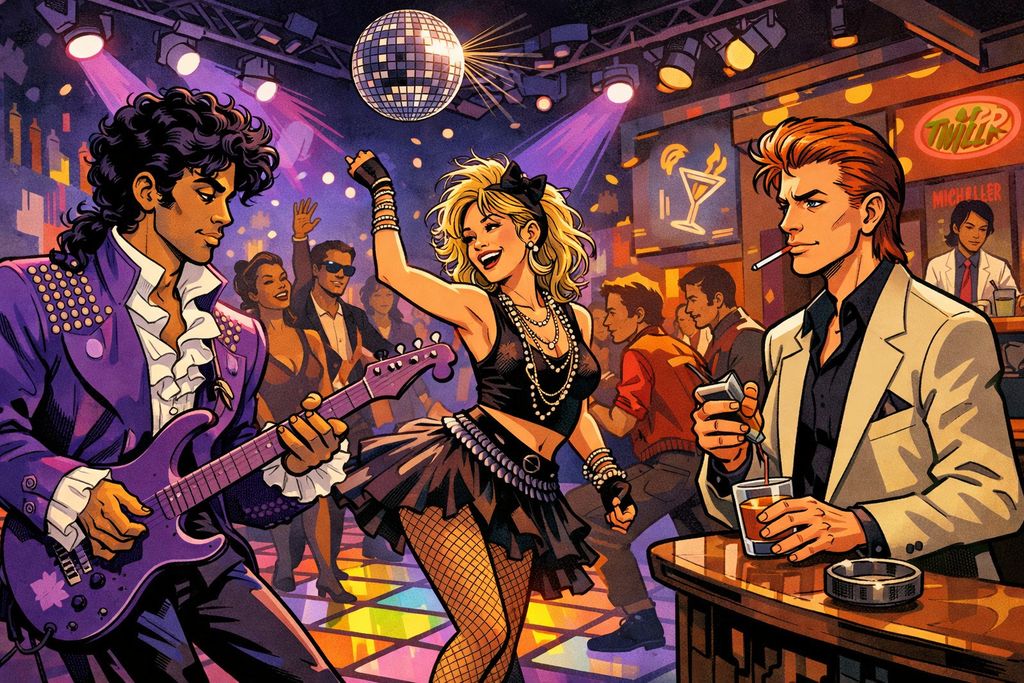

By the late 1970s, the most common models of the previous decade were facing challenges. Rock music had become too big and boring. Disco music had become overused and unpopular. Punk music was popular for a short time, but it was shocking to the public. Artists like David Bowie showed a new kind of future, especially in his work from the Berlin era. He used sound, atmosphere, and identity in fluid, unfixed ways. Groups like Talking Heads and Blondie mixed different types of music without thinking that genres were set in stone.

The most important shift was structural. In the 1970s, success was mostly about albums, touring, and avoiding heavy media exposure. By the early 1980s, singles became popular again, radio stations started playing similar music, and how songs looked on the radio became as important as the music itself. Music became popular, could be played over and over again, and was put into a simple format so that many people could hear it. This helped artists who could adapt quickly and hurt those whose work needed time and subtlety to develop.

The audience also split into different groups. The idea of a single shared mainstream became less strong. Rock was no longer the voice of the people, and neither were soul and disco. The listeners divided themselves into groups based on the shows they watched, the formats of the shows, and the identities of the listeners. Some singers like Donna Summer could easily move from disco to pop music with electronic influences. Others, however, were unable to do so because people’s tastes in music and radio stations changed.

Labels became more cautious and powerful. Budgets increased, and so did expectations. Artists were increasingly asked not only to create music, but also to contribute to broader stories that could be sold internationally through various media. The tension between creative ambition and market discipline was felt throughout much of the decade that followed.

People still believe that music is an important part of culture, just like it was in the 1970s. The environment it had to survive in was different. The 1980s did not erase the past. They reorganized it in ways that were often hard to see at first but impossible to change later.

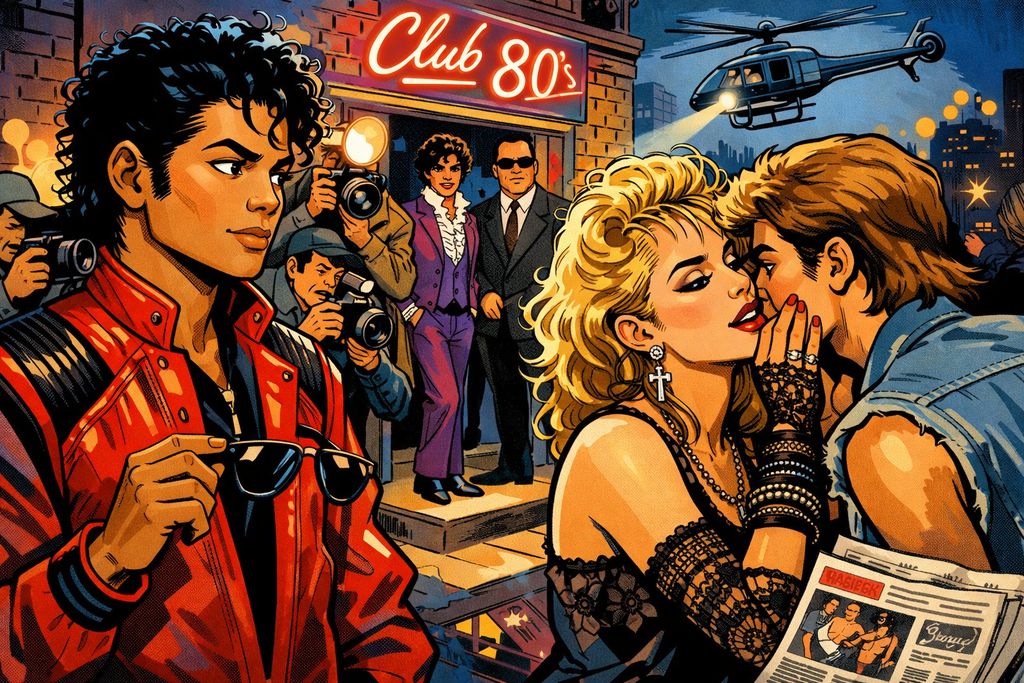

Michael Jackson, Madonna, Prince: The Rise of Global Icons

The idea of the global pop star didn’t begin in the 1980s, but it accelerated during the decade. In the past, famous musicians from the United States were popular in other countries, but they could only reach a limited number of people. This was because they had to plan their tours carefully, and radio stations in different countries only played their music for a limited time. Also, each country had its own music market, so it was hard for musicians to reach a large audience. By the 1980s, those limits were gone. Music spread around the world quickly, images traveled far, and a few artists got a lot of attention from the public.

Michael Jackson is the best example of this change. The album Thriller was released on November 29, 1982. Quincy Jones produced it. It was more than just a successful album. It was number one on the Billboard 200 charts for 37 weeks, a record that has not been beaten to this day. It also won eight Grammy Awards in one night. Jackson changed what people thought a pop career could be like. The record’s sound was a mix of funk, rock, soul, and electronic music. But its impact went beyond music. Jackson’s videos, dance moves, and public appearances made him a famous worldwide star. This helped him reach fans who shared little in common with him. Pop music went from being a local genre to a worldwide sensation.

Artists like Madonna and Prince showed that having the same kind of popularity all over the world doesn’t have to mean being the same. Madonna’s rise, especially around “Like a Virgin,” showed how she used control over her image, sexuality, and provocation in a strategic way, instead of just going along with it. The song “Like a Virgin” (1984) sold over 10 million copies in the United States, which means it was certified multi-platinum. Prince mixed different types of music and styles in his work. He also mixed different ideas, like gender expression and who makes the music. He wanted to be in control of his music, even though he was a famous artist. Purple Rain (1984) sold over 22 million copies worldwide, making it a multi-platinum record.

The rise of stars like Whitney Houston showed that being popular around the world could be more about being clear and careful than about trying new things. Her early recordings showed that she had technical skill and emotional honesty that could be understood and liked by people from other cultures. In a time full of shows, Houston’s success showed that a singer’s voice could still get people around the world to pay attention.

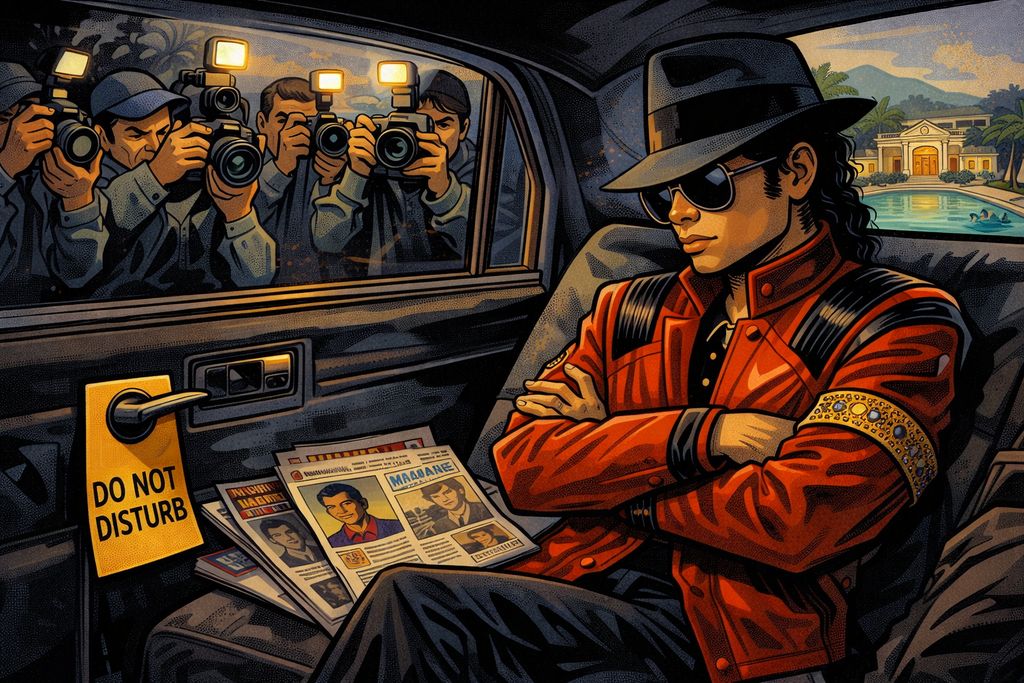

These artists were united by their ability to function within a rapidly expanding media ecosystem, not by a shared sound or image. Different media channels worked together to increase visibility. Instead of being occasional, fame became constant. The pop musician was no longer only heard during a hit cycle. People saw, discussed, and evaluated them almost all the time.

This change brought both opportunity and pressure. The rewards were huge, and so were the expectations. The 1980s did more than just make pop stars famous. They put them at the heart of cultural life. There, music, identity, business, and criticism became all mixed together.

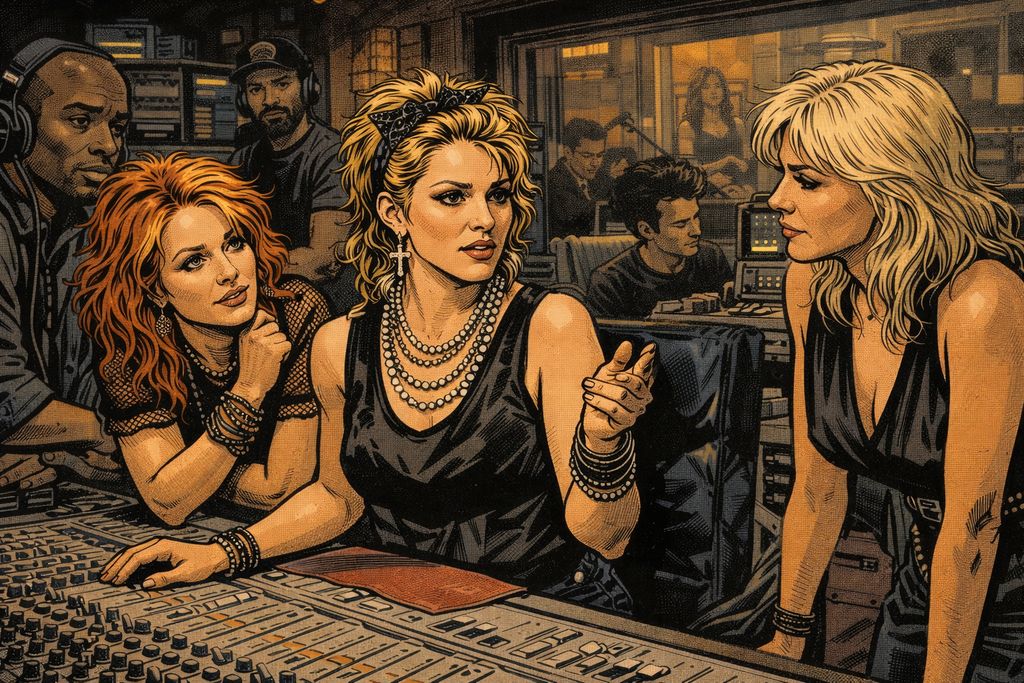

The Image Era: Music Learns to Be Seen

By the early 1980s, people were using music in new ways. It arrived with faces, gestures, clothing, interviews, and carefully crafted stories. Images have always been important in popular music, but during this decade, the balance between images and music changed. The way people understood, judged, and remembered music was closely tied to its visual identity.

Artists like Grace Jones used images not just for decoration, but as part of their art. Her work combined music, fashion, photography, and performance into one style that went against traditional ideas of gender, beauty, and power. Jones didn’t just show up out of nowhere. She was the perfect example of it, turning her public image into a living representation of the sound. She made it clear that the image could be confrontational, intellectual, and deeply intentional.

For many bands, having a visual identity that people could understand quickly became important. Duran Duran used cinematic videos and a highly glamorous style to show that pop music could be something people aspired to and that could succeed globally. Culture Club made gender expression and the mix of different cultures part of everyday life in people’s living rooms. These images were important for two reasons. First, they were striking. Second, they allowed audiences to recognize and categorize artists right away. In a busy media world, having a clear sense of who you are as a person became essential for survival.

This focus on image changed what people expected from musicians. Artists were increasingly asked to explain themselves, perform consistently, and live according to narratives that were often shaped by managers, record labels, and media outlets. People started to disagree about what it means to be authentic. Some performers embraced self-mythology, while others struggled against roles that felt forced instead of chosen.

For women and gender-nonconforming artists, these pressures were especially intense. Being visible meant new opportunities, but also constant scrutiny. People talked about clothes, bodies, relationships, and how others acted, just like they would about songs and song lyrics. The line between artistic expression and public consumption became blurred, and sometimes this was uncomfortable.

This change was not only a loss. The 1980s opened up new ways to be creative. Images let artists express themselves using symbols. They let artists tell stories that sound alone could not carry. They also let artists use humor, exaggeration, and critique. It made space for irony and play.

In the 1980s, music did not give up sound to focus more on visuals. It learned to coexist with them. Songs became like chapters in a book. Artists became like authors of the worlds that listeners entered as well as heard.

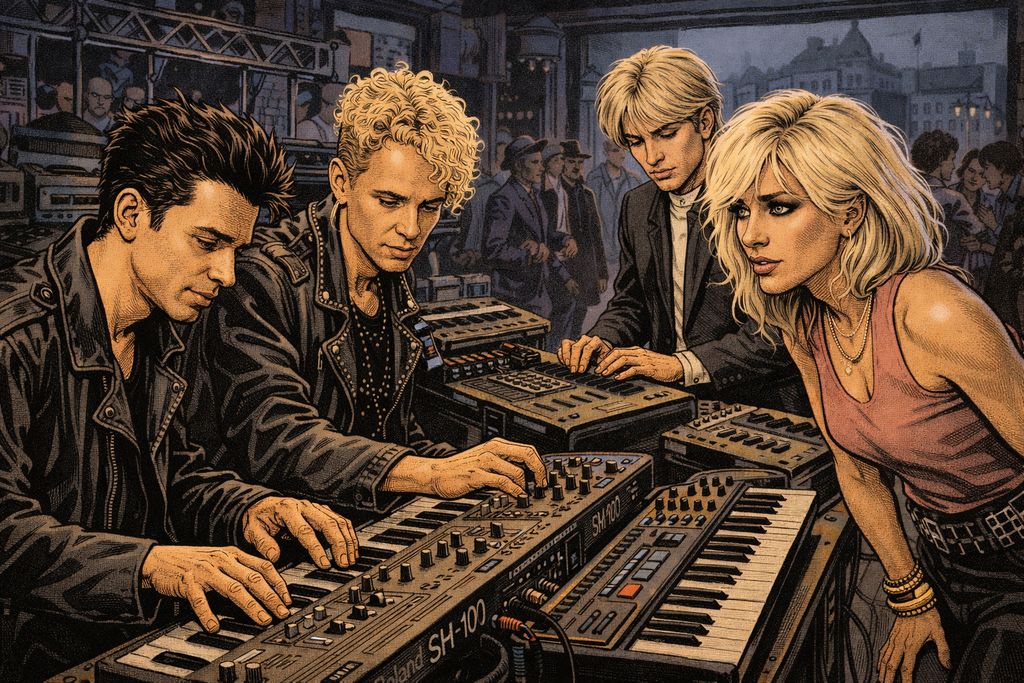

Technology Becomes the Sound

Technology had always influenced music, but in the 1980s, it became a key part of the creative process. This was the first decade when new tools changed the way music was written, recorded, and imagined. They did not just improve the sounds that already existed. Many artists started using technology not only in the studio but also when writing songs.

Changes came quickly and in an uneven way. Synthesizers, drum machines, and digital recording systems became more affordable. This meant that more people could make music and the types of music that people could make changed. In the past, it was common for people to learn to play an instrument as a way to express themselves. However, this was not the only way to do so. All you need is a bedroom, a basic setup, and curiosity to get started. High-end studios started to use more complicated technology. This allowed the producers and engineers who understood how to use it to have more control over the studios.

This technological shift was both exciting and worrying. Some musicians liked the clarity, precision, and potential of electronic sound. Others were worried about losing warmth, perfection, and human touch. These debates weren’t just theoretical. They had a big impact on music. They helped create popular albums, shape the careers of musicians, and create new types of music.

To understand 1980s music, you have to understand the tools that were used to make it. These tools weren’t neutral machines; they were forces that quietly changed creativity, access, and control.

Synths, Drum Machines, and the Sound of Tomorrow

Synthesizers and drum machines were once tools used by a few. Then, they became popular and were used by many people. This change brought more than new textures. They changed the grammar of popular music. In the past, it was necessary to have a full band or to spend a lot of money to record in a studio. Now, a single person can create a song, often working alone. This change affected both the sound of music and how people imagined it from the very beginning.

Artists like Gary Numan were among the first to bring synthesizers into the mainstream without feeling embarrassed about it. His work used electronic sound in a normal way, not as something new and strange. Cold, rigid tones became expressive on their own. They reflected modern life, isolation, and control. Groups like The Human League and Yazoo showed that electronic music could be both emotionally direct and commercially successful, even when it was built on minimal arrangements.

The tools themselves mattered. Drum machines like the Roland TR-808, made from 1980 to 1983, created rhythms that felt mechanical, repetitive, and strangely alive. These patterns were not based on human drumming. They replaced it with something new. At first, fewer than 12,000 808s were sold at a price of $1,195. This shows that it was a commercial failure. However, the 808’s special analog sound, described as clicky, robotic, and spacey, found a small group of fans among underground musicians. Marvin Gaye’s 1982 song “Sexual Healing” was one of the first hits to use the 808 sound. This sound became important in pop music, as well as in R&B, hip-hop, and dance music. The predictable rhythms and artificial sounds forced musicians to rethink how they create music.

Synthesizers also made it hard to tell the difference between a musician and a technician. Programming a sound required patience, experimentation, and a willingness to learn. Often, the systems were poorly documented. This worked well for musicians who thought of music as a process, not just a performance. Bands like Depeche Mode used electronic music to create a whole style. This showed that you could have depth and emotion without using traditional instruments.

These developments raised questions about authenticity. Some people were afraid that machines would replace musicians or that if machines could play music perfectly, musicians would lose their creativity. The music told a different story. Electronic sounds became a way to express vulnerability, desire, and tension. They reflected cities, technology, and changing social rhythms more closely than many recordings that were made using natural sounds.

By the mid-1980s, synthesizers and drum machines were no longer seen as symbols of the future. They were part of the present. They had a big impact on pop music, pushed the boundaries of rock, and paved the way for genres that would become popular decades later. The music of the 1980s was new and different, but it didn’t forget about what it means to be human. It made it into a strange and often uncomfortable form.

Producers Take Over: The Studio as Creative Lab

As the 1980s went on, the recording studio stopped being a place where music was just recorded and became a place where it was actively made. Layers were built one piece at a time, sounds were edited instead of being performed live, and decisions made after recording often mattered as much as those made before. This change made producers and engineers more important. They became central to the creative process instead of just doing technical work.

Quincy Jones is a great example of this change. His work on Michael Jackson’s Thriller showed how production could combine precision and emotion. Every sound felt planned, from the tight drum beats to the precise placement of the vocals. Jones understood that technology isn’t meant to take away humanity. Instead, it’s meant to shape it. The studio made improvements to performances without changing their impact. They created records that sounded polished but still lively.

Producers like Trevor Horn saw the studio as a laboratory. Horn treated recording like a kind of composition. This was true of his work with The Buggles and later with Yes and Frankie Goes to Hollywood. Sounds were layered, reshaped, and sometimes completely replaced. The most important thing was not how something was played, but how it sounded when it was played through speakers. This way of thinking became more common as digital tools got better.

People like Nile Rodgers combined old traditions with new technology. Rodgers was inspired by funk and disco, and he used drum machines and digital recording to create music that had a good beat and sounded warm. His productions showed that clarity and rhythm could exist together, and that technology did not replace physicality.

This new approach, which focused on the studio, changed the balance of power. Artists who understood how things were made had more power. Those who depended entirely on engineers had less control over the final result. There was more and more distance between the performers and the producers. This sometimes led to problems, but sometimes it also led to new and creative ways of working together.

The studio also changed time itself. Songs could be changed over and over again. The singer’s voice could be pieced together from different takes, and mistakes could be quietly erased. This perfection came at a cost. Some musicians felt disconnected from their own work. Others felt more creative in an environment where they could shape ideas without the pressure of performing live.

In the 1980s, the studio did not prioritize musicianship. It changed the meaning of the term. Knowing how to play an instrument was still important, but knowing how to shape sound after it was recorded became equally important. People performed music, and more than just music. It was put together and, in many cases, created in the studio.

Who Could Afford the Future? Access and Inequality

New technology made it easier for people to be creative in the 1980s, but not everyone had the same opportunities. The promise of accessibility was limited by money, geography, and social structures. Synthesizers, drum machines, and digital studios made some things easier, but they also created new challenges that were harder to overcome.

Early electronic instruments were cheaper than using a full studio, but they weren’t free. Many musicians didn’t have the financial stability to buy a reliable synthesizer or drum machine. Artists from middle-class backgrounds, or those already connected to industry networks, were more likely to experiment freely. Others had to share equipment, borrow time, or had insufficient funding for their community studios. This imbalance affected who could learn, improve, and ultimately master new technologies.

Gender was a big part of this difference. Studios were mostly male-dominated spaces, both in terms of the technical aspects of their operation and in terms of their social atmosphere. Women were often seen as singers instead of producers or engineers. This meant that they had less access to the tools that defined authorship in that decade. Even very successful artists like Kate Bush had to fight for control over their work, even though they were clearly skilled and had a clear artistic vision. She was often not treated as someone who could produce and shape her own work.

Race and geography made it even harder for people to get there. In many Black and working-class communities, especially in American cities, building a basic studio setup was expensive. This constraint made people more creative. Hip-hop producers used affordable drum machines and samplers in new ways, making the most of their limitations to create a unique look and feel. What started as necessity evolved into lasting innovation. This shows that creativity can succeed even when there are not many resources. Recognition and money were not always given, especially as larger record companies later made money from sounds that came from outside their own studios.

In places outside of the United States and Western Europe, there were more significant access gaps. Restrictions on imports, differences in currency, and political systems determined who was able to obtain equipment. Musicians in some parts of Eastern Europe, Africa, and Latin America often used old or improvised equipment. This led to the creation of unique sounds that blended traditional methods and cultural influences. These scenes were full of life, but they weren’t often written about or given the same level of support as those in the West.

The story of technology becoming available to everyone in the 1980s is only partly true. Tools spread and changed music a lot. Access was still unequal, which meant that existing inequalities were not being reduced. This explains why some voices became popular quickly, while others were harder to find, even though they were just as original. Technology made more possibilities available, but it didn’t spread them out fairly.

The Digital Trap: Perfection and Its Discontents

In the 1980s, digital tools became more common. This caused a quiet psychological shift. Music no longer felt temporary. The recordings sounded more polished and precise, like they were made to last. Some artists liked that this made them feel like their work would last. For some people, it caused worry. They felt afraid that once something was recorded, it could not be forgotten or stopped feeling.

Analog recording had a sense of movement. The quality of the tape was inconsistent, the mixes were different each night, and the performances changed from one night to the next. Digital recording made things final. A song could be kept in an ideal version, and it could be played over and over again without getting old. Musicians liked this precision because it gave them control and clarity. But it also raised some uncomfortable questions. If a recording could be perfected, when was it truly finished? If a sound became outdated, how easily could an artist move past it?

Some musicians were skeptical. Neil Young, for example, disliked early digital sound. He thought it made music feel cold and empty. His reaction was not simple resistance to change. It reflected a wider concern that technology was making people value clean surfaces over human presence. For Young and others, the imperfections of analog recording were not flaws but proof of life.

Younger artists and producers often saw digital tools as freeing. Precision meant consistency. Sounds could be recalled, replicated, and refined across projects. This was especially helpful during a time when everyone was always visible and it was easy to compare yourself to others. A unique sound could help an artist stand out in a busy market, even if it meant staying within a certain style.

People were afraid of becoming obsolete, and this fear spread beyond sound. Technology was changing quickly, and the equipment was getting old fast. One year, a synthesizer that felt revolutionary could seem outdated the next. Musicians felt pressure to keep up, both in their creativity and in their finances. If a band falls behind the times in terms of technology, it might become irrelevant, even if the music is still good.

This tension made people feel nostalgic for the 1960s right away. New tools were celebrated, but some artists preferred to continue using older methods to express their identity and maintain their connection to the past. Others were ready for the future. They knew that change was unavoidable and often difficult.

The 1980s did not answer these questions. They created a situation that has only become worse since then. Music became more permanent, but also more easily replaced. The worry that came with this change was not caused by technology, but it was a common emotional reaction to it.

MTV: The Channel That Changed Music

When MTV started broadcasting in the early 1980s, it had a big impact on popular music. This impact was felt right away and will be felt for a long time. Music and images have always gone together, but now they’re more connected than ever before. Songs came with pictures of people, and those pictures appeared again and again in bedrooms, living rooms, and public spaces around the world. Listening and watching became the same thing.

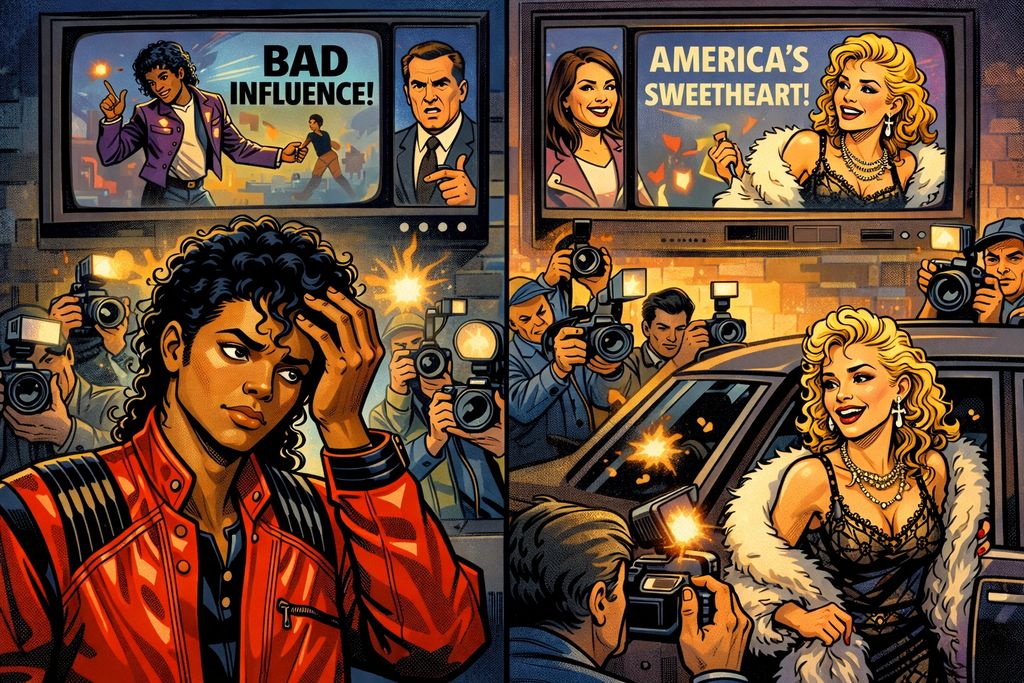

This change affected how artists were discovered and how their careers were built. A strong song was still important, but now it had to compete with other factors. These factors include charisma, visual storytelling, and the ability to hold attention within a few minutes of screen time. Some musicians saw an opportunity here. For some people, it created new problems that had little to do with sound. People’s choices about race, gender, appearance, and genre determined who was shown and who remained unseen.

MTV made fame move faster. Artists were no longer discovered through radio and touring alone. Exposure could be sudden and overwhelming. Success came quickly, and so did criticism. Music videos were praised, criticized, and replayed so much that they became a part of our shared cultural memory.

This shift becomes clearer in MTV’s rise, which turned music into a culture of seeing and being seen, making some artists more visible than others and expanding corporate power.

The Color Line on MTV: Who Got Played

MTV started on August 1, 1981, at 12:01 a.m. with the promise of a new way to experience music, but it was not as successful as hoped. The channel said it was a neutral platform for youth culture, but the shows it chose showed long-standing biases in the industry instead of challenging them. Rock music, especially white guitar-based rock, was the most popular kind of music played on the radio. At the same time, many Black popular songs were treated as less important or not right for the radio format.

The first video played on MTV was “Video Killed the Radio Star” by The Buggles. This was a symbolic choice that set the tone. Early playlists featured artists who fit the typical image of pop and rock music. Executives believed that this type of music would appeal to a presumed white, suburban audience. This assumption had a big impact on visibility. Black artists like Grace Jones, Prince, Eddy Grant, Tina Turner, and Donna Summer were creating new and exciting music in pop, R&B, funk, and dance. But their videos were often not shown on TV, or they were shown late at night when fewer people were watching.

This imbalance became harder and harder to justify. The barrier only broke after Walter Yetnikoff, the president of CBS Records, threatened to stop selling CBS music to MTV. This forced MTV to play Michael Jackson’s music videos. Artists like Prince and Michael Jackson were impossible to ignore. They were famous not only for their music, but also for the way they used music videos to push the boundaries of what was possible. Jackson’s work made MTV realize that it had its own limitations. When videos from Thriller were played a lot on the radio, they did more than make the ratings go up. They showed that the channel’s genre categories weren’t as clear-cut as they seemed.

Inclusion was often given with conditions. Black artists who became famous after death were expected to meet visual and stylistic standards. These standards were shaped by the same people who had excluded others. Artists who focused too much on funk, soul, or political expression received less support. The channel said that it was just responding to what the audience wanted, but in practice, audience taste was being shaped by what they were allowed to see.

Gender bias was also a factor. Women artists were easy to see, but people often thought of them in a limited way, as pretty and marketable. The image was closely examined, and anything that didn’t align with common standards could lead to reduced visibility. MTV did not create these pressures, but made them worse by turning visibility into a daily competition.

Despite these problems, MTV became a place where people negotiated rather than just following orders. Artists learned to use the platform in smart ways, testing its limits from within. The channel slowly changed things over time, but the early years had a long-lasting impact. New forms of media rarely come without old hierarchies. The 1980s brought big changes to how music was presented. These changes made music more popular, but they also showed who was included and who was left out.

The Music Video Becomes Art Form

As MTV became a must-watch channel, some artists and directors started treating music videos as more than just a way to promote their music. What started as a way to market products has become a place where people can try new things, tell stories, and create visual content. Videos, when made with the right people, could turn a song into a short film that made people feel more emotional and think more deeply about the song’s ideas.

Peter Gabriel is one of the best examples of this. His videos weren’t just about glamour or performance. They focused on symbolism, discomfort, and visual metaphors. Songs like “Sledgehammer” and “Shock the Monkey” used stop-motion, makeup, and strange images to show inner feelings instead of actual stories. Gabriel knew that the video could show something the song only suggested. It would add another layer to the message instead of repeating the same idea.

This approach got musicians and directors working together, and they saw the format as an artistic challenge. Filmmakers like Russell Mulcahy helped create the visual style that defined the decade. His work focused on movement, editing, and atmosphere, often influencing how people remember songs. In many cases, the video and the music became closely connected, especially for artists whose careers happened at the same time as television.

High-production videos raised the bar for pop and R&B artists. Janet Jackson used dance moves and a consistent style to show discipline, confidence, and control in the second half of the 1980s. Her videos were more than just performances. They also conveyed her professionalism and authority. The camera made the identity stronger.

Some artists chose to keep things simple. The animated line-drawn world of A-ha’s “Take On Me” showed that innovation doesn’t always need to be spectacular. The video mixed illustration and live action to create a romantic yet delicate atmosphere that matched the song’s emotional tone. Visual ideas can make vulnerability seem stronger than it is.

Not every artist accepted this new demand. Some people felt that the expectation to produce visually striking work was distracting or too personal. The medium was shaped by resistance. Choices that used to be minimal, awkward, or deliberately plain now became their own statements.

By the mid-1980s, music videos had become a well-known art form. It had a big impact on fashion, movies, ads, and pop culture. People no longer listened to songs on their own. They arrived with images that helped people understand, remember, and respond emotionally. The music video didn’t replace listening. It changed how people thought about sound. It showed people that sound could be seen, understood, and remembered. It did this by using images that people could see even after the music stopped.

Bodies on Display: Gender, Power, and the Camera

In the 1980s, visibility became essential for success. Because of this, the body itself became a place where people negotiated. The image was no longer just an extra part of music. It was a requirement for participation, but this requirement was not applied equally. Women artists had to deal with a difficult situation. They were expected to be both visible and acceptable. At the same time, their appearance was judged as much as their sound.

Artists like Madonna understood this pressure early on and chose to face it directly. Instead of just going along with what people expected, she used clothes, sex, and shock tactics as tools to express herself. Her videos and public appearances made people think differently about what it means for a woman to be in the spotlight. People used control over images as a way to show their power, but it also led to negative reactions. Madonna’s strategy worked because it exposed and redirected objectification, not because it avoided it. Her work with “Like a Prayer” (1989) in the late 1980s is a good example of this approach. The song reached #1 on the Billboard Hot 100 for three weeks in a row and sold over five million copies around the world.

For some people, the experience was not as empowering. Cyndi Lauper had a playful and unconventional image. She didn’t fit the traditional glamour mold, but people often thought of her as a novelty rather than a serious songwriter. Tina Turner’s return to the stage was often discussed in terms of her body and age more than her voice, even though she had a long career and was a highly respected musician. People praised him, but they rarely said anything positive. It was filtered through surprise, comparison, and judgment.

Body politics also determined who was considered suitable for constant rotation. The media often showed thin people, young people, and people who fit a certain beauty standard as being the most attractive. This made people think that only these types of people were attractive. Artists who didn’t fit these categories faced different forms of exclusion. Even when women were successful, people often expected them to be emotionally available, sexually appealing, or willing to share personal information in the same way that male artists were rarely asked to do.

Men were not completely free from these pressures, but the standards for them were different. Masculinity could be exaggerated, stylized, or even theatrical without people questioning whether these portrayals are real. Gender-nonconforming artists broke with these norms, but they did so at great personal and professional risk. They often became symbols rather than individuals in media stories.

The camera’s constant presence made these dynamics even stronger. They recorded mistakes, changes in appearance, and moments of vulnerability and then watched them back. Privacy shrank. The difference between who a person really is and how they act became bigger, and it was sometimes hard to manage. These images also had a big impact on younger audiences. They influenced ideas about gender, success, and self-worth in ways that were rarely talked about at the time.

The 1980s did not invent body politics in music, but they made it louder. Images became the new form of currency, and this currency was distributed unequally. To understand the decade, you have to understand the pressure it faced. It wasn’t just a time of confident icons. It was a time when being seen meant paying a price, and being strong was often as important as being talented.

Pop Takes the Throne

By the mid-1980s, pop music was no longer just one genre among many. It had become the center of gravity. Pop artists became highly successful, and that success translated into cultural influence. They shaped how people talked about identity, desire, and everyday life. These conversations were about more than music. This was not accidental. It showed how the industry had learned to produce global success by aligning media, technology, and narrative around individual performers.

In this decade, being popular was closely related to having power. This meant that people could define trends, cross borders, and control their own image and output, at least in part. However, this power was not distributed equally. Some artists were able to say that they were the ones who created a work and that they had full control over it. This was possible in a system that was designed to make rules and make money from art. Some people were promoted quickly, but then they realized that being promoted meant they had to meet new expectations.

The worldwide popularity of pop music also made people question what makes something authentic. Music that was easy to travel with often had to balance being specific with being accessible to a wide audience. People’s accents, styles, and identities were being decided right away. They were being shaped by the market as much as by artistic intent. At its best, this brought people from different continents together to share cultural experiences. At its worst, it made things too predictable by using the same methods every time.

What follows connects creativity, control, and business success. It shows who gained power, who fought back, and how global fame changed what success meant.

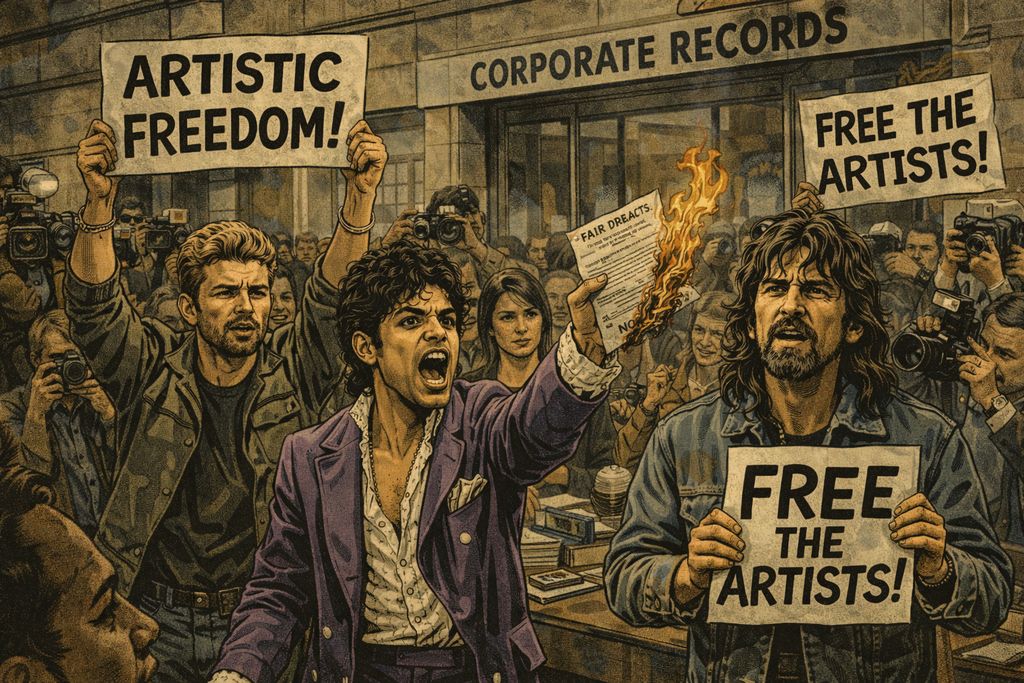

Prince, Kate Bush, and the Fight for Creative Control

One of the most important questions in 1980s pop music was about who should be considered the “author” of a song. As the industry grew larger and more organized, creative control often moved away from performers and towards labels, producers, and marketing teams. Some artists did not like the idea of having different jobs. They wanted to have control over how their music sounded, how it was written, and how it was produced and presented to the world.

Prince is a great example of this. He approached pop music from a personal perspective, handling everything from writing songs to choosing instruments to producing the final product. He didn’t see it as a collaborative effort where everyone had to compromise, but rather as a way of expressing himself individually. Albums like 1999 and Purple Rain were not made by a group of people working together. They came up with a unique style that was inspired by funk, rock, soul, and electronic music. Prince was in control not only of his music, but also of his image. It was also political. He took ownership of his work, which went against the way the industry usually worked. Usually, performers were seen as mere interpreters, not creators.

A different, quieter form of authorship emerged through Kate Bush. Her approach was to experiment in the studio and take her time developing her work, rather than being constantly visible and touring. Bush used the recording studio to create music. He used it to write songs, arrange music, and experiment with sounds. Albums like Hounds of Love showed that pop music can be detailed, thoughtful, and structurally ambitious without losing its emotional connection to the listener. Her success showed that being independent didn’t always mean arguing. Sometimes it was necessary to stop.

For artists like George Michael, the fight for control became obvious and public. Michael wanted people to know him as a songwriter instead of just as the lead singer of a popular band. He wanted to move away from the commercial style of his band, Wham!, and focus more on his own artistic style. His later disagreements with record labels showed a bigger problem of the decade: the desire to improve as an artist within a system that preferred simple, successful ideas over change.

These struggles were not one-time events. Musicians were starting to understand that being successful in the pop music industry meant having invisible contracts, both legal and narrative. These contracts were about the expectations for an artist’s image and persona. To take back the title of “author” meant risking the stability of your business, the media’s support, and sometimes your career’s progress.

The artists who took control left a lasting mark. They broadened the range of what pop could include. People’s unique ideas, technical curiosity, and refusal to be easily categorized became possible options that many people could get on board with. By doing this, they revealed an important truth about pop music in the 1980s: it was powerful because it combined creativity with structure. People who learned to deal with that tension changed the decade from within.

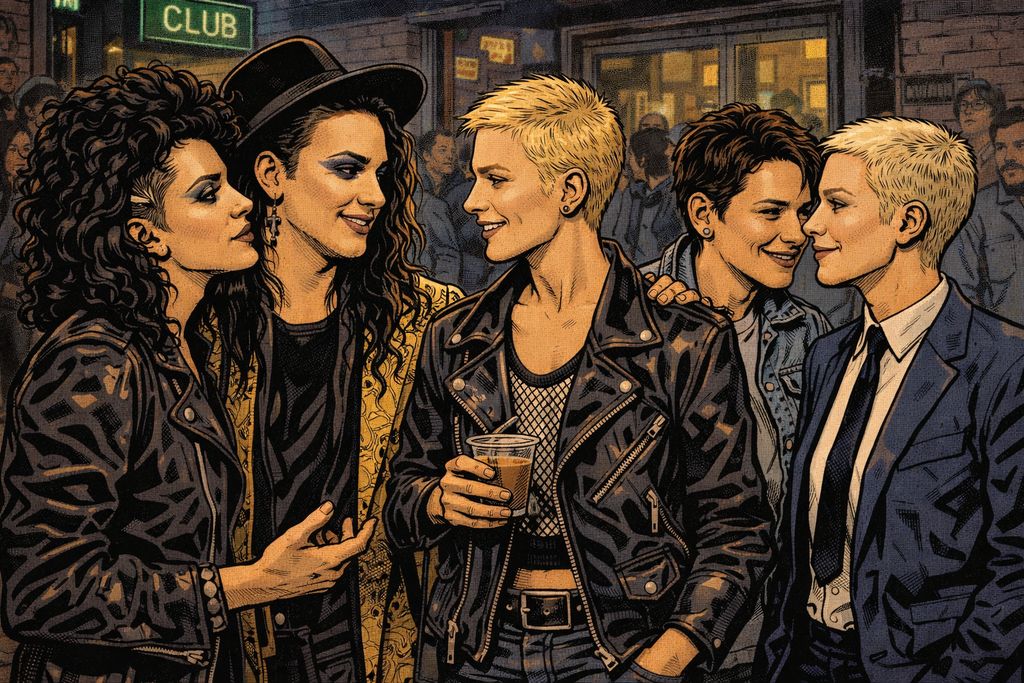

Madonna, Whitney, Janet: Women Who Ruled the 80s

For women in 1980s pop, being visible was never neutral. Being seen meant opportunity, but it also meant being interpreted all the time. Every action, clothing choice, and voice tone was influenced by expectations that often conflicted with each other. Women were expected to be easy to relate to but also exceptional, in control but also open about their emotions, and attractive but not threatening. Finding a way to deal with these demands required both good judgment and skill.

People often use Madonna as an example, but her importance lies not only in her ability to provoke. She thought about visibility as a space that needed to be managed. Instead of showing one consistent image, she changed her style often, using religious symbols, fashion trends, and discussions about sex and gender. Her constant movement made it hard to describe her in just one way. Control means staying one step ahead of scrutiny, not avoiding it.

A different model emerged through Whitney Houston. Her rise was based on her clear voice and emotional accuracy, not on conflict. Her first album, which is named after her, was number one on the charts for fourteen weeks in a row. It sold over 10 million copies in the United States, which means it was certified Diamond. It sold over 25 million copies around the world. Its singles were popular: “Saving All My Love for You” was #2 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart. “How Will I Know” reached the top ten, and “The Greatest Love of All” was #1. Houston’s success showed that women didn’t have to choose between being well-known and being approachable. Even in her case, people’s expectations about how she looked, how her work could be liked by a wide range of people, and how she acted in public affected how her work was received and discussed.

Janet Jackson showed another way, one based on discipline and a shared vision. Her work with producers Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis made the music, dance, and images work well together. Albums like Control showed independence not as a form of rebellion, but as a way of defining oneself. The album Control was number one on the Billboard 200 chart for fourteen weeks. In the United States, it sold over 10 million copies. Its singles did very well on the charts: “What Have You Done for Me Lately” was #4 on the Billboard Hot 100, “Nasty” was #3, “When I Think of You” was Jackson’s first #1, “Control” was #5, and “Let’s Wait Awhile” was #2. Jackson’s work showed how structure itself can be empowering, especially when artists are involved in creating it.

Artists like Sade didn’t want to be part of the spectacle. With simple visuals and performances that weren’t over-the-top, she created an atmosphere where being personal and steady was more important than always changing. This decision not to go beyond what was required became a statement in itself in a culture that valued noise and speed.

These different strategies meant that women artists were often discussed in ways that made it seem like they had little control over their own lives. Success was often explained as image management, not authorship. Aging was framed as decline, and ambition was reframed as calculation. These narratives did not reject achievement, but they limited how it could be understood.

The impact of these artists was undeniable. They expanded the emotional range and themes of pop music, proving that visibility did not require uniformity. They negotiated power on their own terms. This changed the center of popular music. They also created examples of how people can be strong and survive. These examples are still important today, even though the problems that caused them are no longer happening.

From Europe to Australia: Pop Without Borders

The United States and the United Kingdom were still the most important countries in the 1980s pop economy. But the decade also marked a turning point for artists working outside of these centers. Pop music can circulate in ways that were far more limited in earlier decades. This is because of improved distribution, satellite television, and international touring networks. As a result, the music industry was no longer defined by exports from hubs in the United Kingdom and the United States. It started to show regional differences, including accents and concerns, while still trying to be accessible in other countries.

In continental Europe, artists like Falco showed that language itself was not a problem. The song “Rock Me Amadeus” by Falco was a major international hit. It was number one on the US Billboard Hot 100, number one in the UK, and number one in Germany. It was the first German-language song to be number one in the United States. The song “Der Kommissar” (1982) was #5 on the US Billboard Hot 100, #1 in Austria, and #1 in Germany. These songs combined German lyrics with international pop music styles. This made local details interesting, instead of limiting the songs. Falco’s success showed that people around the world were open to different types of content, as long as it was presented in a confident and clear way.

Scandinavian pop also became popular again during the decade. ABBA was already around earlier, and their continued presence in the public’s mind influenced a new generation of artists. These artists thought that polished songwriting and emotional directness were important qualities in music. Later in the decade, performers like Kylie Minogue, who was Australian, became part of a larger international pop network based in Europe. This shows how geography and identity became more flexible within the pop system.

In German-speaking countries, electronic and synth-based pop music was highly popular and successful. Groups like Yello used humor, experimentation, and distinctive sound to stand apart from conventional chart pop, while still getting international exposure. Their work showed how electronic music could be a shared language across different countries, even when the lyrics were short or hard to understand.

In other places, pop culture developed in response to the local political and cultural environment. In some parts of Latin America, Africa, and Asia, Western pop music blended with local traditions. This created new styles that were rarely covered by the global media. These artists often had problems getting their music out there, but their music was still deeply important to local youth cultures. It helped shape who these young people were and what they wanted to be when they grew up, which was just as important as being a hit somewhere else.

In the 1980s, pop music from around the world was a kind of shared experience. Artists wanted to reach people all over the world, but they also wanted to stay connected to the places where they lived. Some were incorporated into the main pop culture story, while others stayed on the edge despite strong regional fan bases. This showed that the promise of global connection during the decade was real, but not equal for everyone. Pop music traveled farther than ever before, but it did so along paths influenced by language, the economy, and popularity. This shows us that globalization created more opportunities without eliminating differences.

Rock After Punk: Reinvention and Fragmentation

By the time the 1980s arrived, rock music was no longer a one-way conversation. Punk had made it simpler and shown its limits, but it didn’t replace it with a more unified alternative. Instead, it left a landscape with many different paths. These paths reacted in different ways to the pressures of business, politics, and identity that defined the decade.

Some artists decided to expand. Bigger stages, louder sounds, and wider audiences promised that the most popular music would be the music that was played on the radio and watched on TV. For some people, surviving meant leaving. To maintain independence, smaller record labels, local music scenes, and a deliberate distance from mainstream exposure became strategies. Rock was constantly changing its purpose between these two poles. Was it a big show, a personal statement, or a way to bring the community together?

Technology and the media made these questions even stronger. Synthesizers were a new type of music that changed the way people thought about guitars. MTV also changed how people thought about bands. Touring also made some bands more popular than others. At the same time, there was more variety in the emotional expression of rock music. Anger, introspection, irony, and vulnerability all had their place, but they didn’t always show up in the same spots.

Rock’s response to punk then unfolds in different directions. Some bands embraced punk’s impact, others resisted it, and many landed somewhere in between.

Post-Punk, New Wave, and the Art School Aesthetic

After punk music first became popular, many artists took its intensity seriously, but they didn’t just copy the style. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, musicians started to create music that was similar in some ways, but different in others. They didn’t fit neatly into one genre. Instead, they were grouped together under labels like “post-punk,” “new wave,” and “art rock.” They were all united in their refusal to go back to the old ways of rock music. The term “post-punk” was first used in November 1977 by music journalist Jon Savage in his “New Musick” article for Sounds magazine. In the article, Savage described post-punk as “post punk projections.”

Bands like Joy Division took rock music even further than punk had. They focused inward instead of being confrontational. Their music sounded intense, open, and emotional. Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures (1979) was released in the late 1970s, but it wasn’t until the 1980s that it gained cult status. Today, it’s considered a post-punk classic. Instead of promising release, it documented feelings of anxiety, isolation, and disconnection. This shift towards thinking deeply about oneself was popular with people dealing with economic uncertainty and social change. It also helped create a new idea of what emotional honesty in rock music could sound like.

Other artists chose a more dramatic or textured approach. Siouxsie and the Banshees combined strong rhythms with a dark, eerie atmosphere. They drew on art, fashion, and performance as important parts of their work. Their music was confrontational but not chaotic. It was controlled but also expressive. It showed how post-punk could be both visually striking and conceptually coherent without losing musical depth.

The New Wave style was influenced by post-punk, even though it’s often thought of as a less serious or more popular version of post-punk. Groups like Talking Heads used irony, repetition, and rhythmic experimentation to examine modern life. In the early 1980s, they explored ideas about feeling disconnected from society, the pursuit of material things, and the search for personal identity. Their approach was unique and different from the usual stories told in rock music. Dance rhythms and artistic sensibilities from art school worked together, showing that being serious didn’t have to be heavy.

The band The Cure showed how being consistent in their emotional style could be a new and exciting thing for their fans. Their music moved between minimalism and lush arrangements, and it focused on sadness, longing, and ambiguity. The band The Cure’s album Disintegration (1989) reached number 12 in the UK and went Gold in the United States, which showed that they were becoming more popular. Instead of seeing these emotions as short-term feelings, they let them influence whole albums and periods of music. This made fans who felt the same way but couldn’t find similar music anywhere else become loyal.

What connected these scenes was not sound, but attitude. The post-punk era was from about 1978 to 1984. It was a time when rock music was being redefined. Rock no longer needed to show who’s boss or give answers. It could observe, question, and even withdraw. Post-punk and related styles allowed for more complexity at a time when most popular music preferred being quick and attention-grabbing.

They made sure that rock music stayed important in culture. They did this not by competing with pop music, but by changing what it means to be relevant.

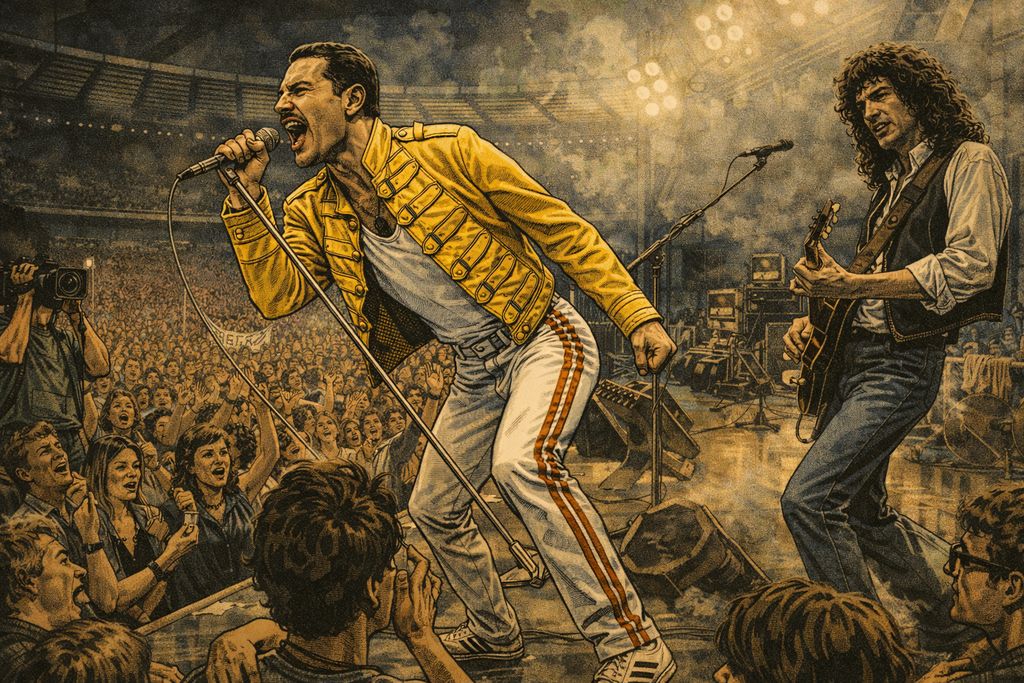

Stadium Rock: Bigger, Louder, Everywhere

Some types of rock music became more focused on themselves after punk rock. Others moved in the opposite direction. In the 1980s, rock music got bigger. Bands used bigger instruments, more volume, and more spectacle to stay popular. Rock music like arena rock, hard rock, and metal remained popular. They embraced it, changing their sound and how they presented themselves to fit bigger and bigger venues and media spaces.

Bands like U2 showed how rock music could stay relevant and express political awareness even when they were performing for huge audiences. The Joshua Tree (1987) was the number one album in the United States and sold 25 million copies worldwide. It won the Grammy Award for Album of the Year in 1988. In the early 1980s, they combined spiritual exploration with a global perspective. Their live shows focused on building connections and sharing experiences with their audience. U2’s success showed that being sincere and being big could go together, even as stadium tours became a central part of who they were as a band.

Hard Rock was more focused on making money. Groups like Bon Jovi and Def Leppard made their sound better for radio and television. They did this by making the music more catchy, the production more polished, and the images more in line with each other. Their music was made to be played over and over again, and it fit perfectly with MTV’s playlists. Bon Jovi’s album Slippery When Wet (1986) reached number one on the Billboard 200 music chart. It sold 12 million copies in the United States and 28 million copies worldwide. The album Hysteria by the band Def Leppard was also #1 on the Billboard 200 music chart. It sold 12 million copies in the U.S. and over 20 million copies around the world. Many critics said this approach was superficial, but its success showed how carefully designed accessibility could help rock music remain popular in a highly competitive music world.

Metal expanded in different ways. Some bands liked to be dramatic and over-the-top. They made a big show out of being loud and aggressive. AC/DC’s Back in Black (1980) reached #4 on the Billboard 200 and sold over 50 million copies worldwide. It is one of the best-selling rock albums of all time. Metallica is an example of an artist who pushed for precision, speed, and technical skill. Metallica started out as a band playing in underground clubs. Even as their popularity grew, their early work still sounded dangerous. Their success showed that heaviness could go together with structure and ambition. This went against the idea that metal could not be cultural.

The economic conditions during this time had a big impact on these styles. Large venues rewarded bands that could play well and impress people every night. This favored clear song structures, images that are easy to recognize, and physical endurance. The demands of constant touring also reinforced certain ideas of what it means to be a man, emphasizing strength, control, and stamina. People often ignored emotional vulnerability and focused instead on confidence and control. However, emotional vulnerability never completely disappeared.

In the 1980s, arena rock and metal were not just reactions against punk or pop. They were responses to a changing environment. In this environment, it was essential to be visible, loud, and repetitive. These genres kept rock music popular by embracing scale. This happened even though other types of music were challenging rock’s dominance. The result was a type of rock music that was louder, more polished, and more popular around the world. However, it was also more closely connected to the systems that supported it.

Indie and Alternative: The Sound of Resistance

During the 1980s, a less visible but still important group of alternative music scenes emerged. These scenes were separate from the popular arena stages and rock music that was shown on television. These communities did not reject rock’s past; they just didn’t like how big it was. For them, being independent was more important than being well-known, and they gained people’s trust by being reliable instead of by being visible.

Bands like R.E.M. started in local scenes. Back then, touring meant playing in small clubs and college towns. It also meant getting known through word-of-mouth. The band R.E.M.’s album Document (1987) reached number ten on the Billboard 200, which is a list of the most popular music in the United States. This was an important moment for the band because it helped them become more popular. Their early work did not use obvious hooks or grand statements. Instead, it focused on creating a certain atmosphere, using ambiguity, and showing restraint. This approach was popular with people who felt disconnected from the mainstream, which is focused on big shows and events. Success came slowly and often reluctantly.

In more unconventional corners, groups like Hüsker Dü, Sonic Youth, and the Pixies challenged traditional ideas of melody and structure. The Pixies’ Surfer Rosa (1988) became a cult favorite. It later influenced Nirvana and alternative rock. Their music used distortion, repetition, and noise. They did not do it just for the sake of being rebellious. They did it to expand what rock could express. These sounds reflected the tension in the city, the frustration of politics, and the desire to be different in the arts. Mainstream radio could not easily accept this.

Independent record labels were crucial in keeping these music scenes alive. Companies like SST Records provided the necessary tools and resources without requiring people to fit into a specific mold. There wasn’t much money, so they could only distribute a limited number of copies. They relied on touring and getting the community to support them. This created ecosystems that were fragile, but it also made artists and audiences form strong bonds. The music felt like it came from the local community and was well-deserved.

College radio stations and fanzines helped connect these scenes across regions. Songs were shared through tapes, recommendations, and live shows, without the help of heavy rotation or video exposure. This slower pace allowed ideas to develop naturally. People start following trends not because someone is forcing them to, but because they find the trends appealing.

Resistance was not absolute. As alternative music became more popular, the music industry took notice. Some artists were careful as they went through this change, while others lost sight of what was important to them. It was hard to balance being independent and being visible, and not everyone chose to cross that line.

What made these underground movements different was not that they were secret, but that they had a clear purpose. They had a different idea of what success meant. They thought success was about having creative freedom, not about market share. In a decade of increasing standardization and polish, these scenes let people try new things, have doubts, and say “no.” They would become more visible in the years that followed, but in the 1980s, they were known for their persistence rather than their dominance.

Black Music in the 80s: Innovation and Barriers

To understand 1980s music, you have to think about Black artists. A lot of the most important new ideas of the decade came from Black musical traditions. But even though these traditions were important, they were not always treated fairly. The 1980s were marked by a consistent conflict: Black musicians had a big impact on the sound of the era, but they often faced systems that made it hard for them to be seen, be recognized as the creators of their music, and maintain control of their work in the long term.

R&B, funk, and soul didn’t disappear when new technology emerged. They took it in and used electronic tools to create languages that were full of rhythm, intimacy, and community. Hip-hop started in local communities and spread across the country and the world. It shared stories that big culture had ignored or told incorrectly. These developments were connected by their shared histories of adapting to and resisting challenges.

Innovation alone does not guarantee fairness. Even when audiences were the same, radio formats, television exposure, and industry hierarchies kept genres separate based on race. Success was often seen as a mix of different styles instead of being based on its own unique style. This made it seem like Black music needed approval from outside its own traditions.

Black creativity is central here not as an abstract ideal, but as work produced under pressure, negotiation, and constraint. That work shaped the decade while also confronting structural limits on how and where it could be shared and remembered.

R&B, Funk, and the Digital Revolution

As the 1980s went on, rhythm and blues (R&B) and funk music went through a period of change that was both technological and cultural. Electronic instruments did not replace these traditions. They were absorbed into them. Drum machines, synthesizers, and digital recording changed how music was made, but the most important things remained rhythm, intimacy, and emotional communication. The result was a body of music that sounded modern but also kept its connection to the past.

Prince was one of the few artists who did this well. During the decade, he saw technology as an addition to music, not a replacement for it. The machines were used in a way that made the sound feel more intense, not less intense. Funk stayed physical, even after it was programmed. Prince’s approach showed that electronic precision could go with sensuality and spontaneity. This challenged the idea that digital sound had to feel detached.

A more subtle form of digital elegance emerged through artists like Luther Vandross. His recordings were warm, in control, and clear. He used modern production techniques to create a sense of intimacy without overwhelming it. Digital tools allowed for cleaner mixes and consistent tone. This supported a style of R&B that prioritized emotional presence over spectacle. This approach was popular with adult audiences who felt ignored by the popular music of the time.

Women played a central role in shaping this evolving sound. Anita Baker’s success in the latter half of the decade showed how digital production could support subtlety. Her music was simple and focused on using space, phrasing, and restraint. During a time when maximalism was popular, Baker’s work was unique because it relied on a simple, strong style.

Group-oriented acts also adapted quickly. New Edition combined old-fashioned vocal harmony with modern production styles. This helped create a model that would influence future generations of R&B and pop groups. Their music was both easy to like and well-made, like how Black artists were often expected to be technically excellent right away and all the time.

There were still structural barriers. R&B was often divided into different types of radio shows and marketing groups, which made it seem less popular. Songs made it onto the pop charts, but people talked about them as exceptions rather than as proof of their importance. This framing made digital R&B seem like just a small part of the music scene, when in reality it was a major influence on the decade’s sound.

The digital change in R&B and funk was a balance between new ideas and staying true to the old ways. Black artists helped shape the future of popular music. At the same time, they faced systems that often did not fully recognize their leadership.

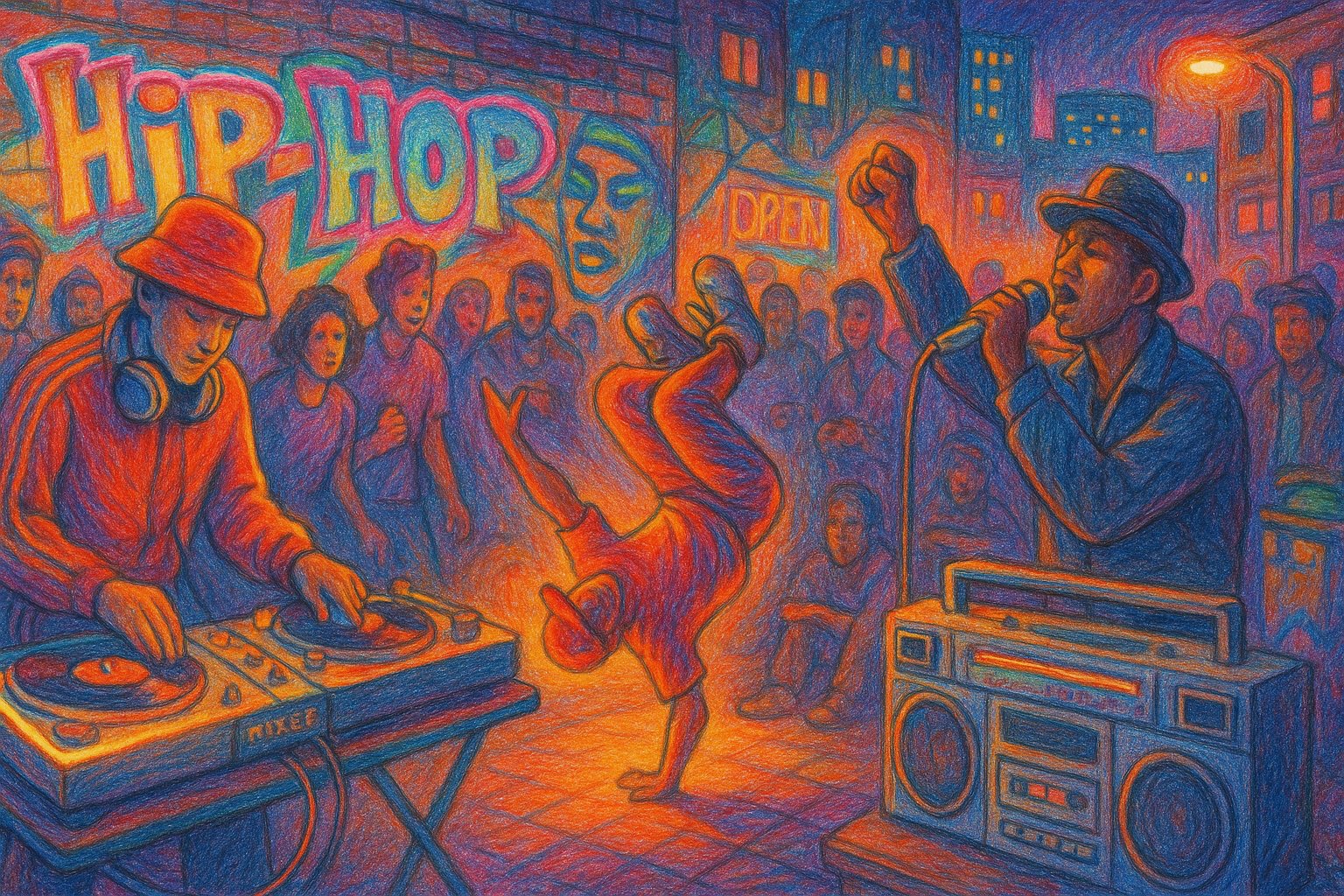

Hip-Hop is Born: From the Bronx to the World

Hip-hop started as a local culture in the 1980s and became a global force by the end of the decade. It did not rise suddenly, and its growth was not smooth. Hip-hop started in New York City with block parties, sound systems, and community spaces. It developed outside of the traditional music industry. This distance influenced both its music and its political views. At first, it was more like a social practice than a genre. It was based on DJing, MCing, dancing, and visual art.

Artists like Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five showed that technical innovation and social urgency could work together. The song “The Message” (1982) was #4 on the R&B charts. It was the first rap song with socially critical lyrics to reach Billboard’s Top 5. This was a big change. It showed that hip-hop could talk about real life in a clear and controlled way. Instead of celebrating escape, it talked about pressure, inequality, and frustration in simple language. This directness went against the music industry’s expectations for popular music.

As the 1980s went on, groups like Run-D.M.C. helped change hip-hop from a style best suited for parties to a more serious, confrontational sound. Their album King of Rock (1985) reached number 52 on the Billboard 200 chart. This showed that they had a wide fan base. They used drum machines, simple music arrangements, and shouted vocals. They did this to create a strong and powerful sound, not a polished sound. The collaboration with Aerosmith on “Walk This Way” (1986) reached #4 on the Billboard Hot 100. This made crossover a symbol of hip-hop music. However, it also showed that hip-hop was often only popular when it was compared to well-known rock music.

By the late 1980s, hip-hop music became more openly political. Public Enemy used music as a way to make a change. They created complex music with clear, direct lyrics. Albums like It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back were different and made people uncomfortable because they were honest about Black political ideas. Their work made it clear that hip-hop didn’t need to ask for permission. It was showing who was in charge.

Hip-hop faced ongoing concerns about its moral impact. News outlets often described it as dangerous, irresponsible, or threatening. The words of songs were closely examined, how performers acted on stage was strictly controlled, and artists were reduced to simple labels. These reactions showed more about the worries the music brought out than about the music itself. Hip-hop openly talked about violence, surveillance, and exclusion. Many people preferred to keep these ideas abstract.

Despite some people’s initial reluctance, hip-hop music quickly gained popularity. Cassette culture, live performances, and the exchange of music among friends allowed it to reach people beyond the radio formats that initially ignored it. It had a big impact on fashion, language, and attitude. It changed youth culture in ways that went beyond its original communities.

By the end of the 1980s, hip-hop was no longer just a small part of the music industry. It became one of the most important voices in popular music. It was based on real-life social situations, and it could change as it moved. This did not mean that old traditions were going to end. It marked the beginning of a change in who was allowed to speak and how directly they could do so.

Crossover and Its Discontents

In the 1980s, Black music became more popular. This made it more visible, but it also made it more difficult to control. Success was often described as “crossover,” a term that seemed neutral but had serious consequences. The term implied that Black music began at the margins and only became central after outside approval. That framing reinforced the idea that Black traditions needed validation from dominant markets.

Artists like Michael Jackson showed the excitement and the pressure of this time. People often called his achievements “breakthroughs,” as if Black artists had only recently started influencing popular music. Jackson’s success around the world clearly broke down racial barriers, but the language used to talk about it often suggested that there were still problems rather than celebrating progress. The recognition came, but it was seen as an exception rather than a fix for an ongoing problem.

This pattern extended beyond pop music. R&B and hip-hop artists who became more popular were often expected to change their music, images, or political messages a bit. Marketability became more important than just having a goal. Music that fit existing commercial templates was more easily accepted across different formats. However, music that remained rooted in specific social realities faced resistance. The result was a system where some forms of Black expression were praised, while others were ignored or misinterpreted.

The situation was made more complicated by appropriation. Elements of Black music, like its rhythms and vocal styles, were often incorporated into popular music, but the artists were rarely recognized or paid for their contributions. When similar sounds appeared through white performers, people often said they were innovative or universal, rather than saying they were imitating other styles. This pattern made it seem like the people leading cultural change were different from those who were actually driving it.

Gatekeeping was carried out through institutions, not just individuals. Radio stations divided their audiences based on race. Television was not widely watched by everyone, and awards did not always recognize shows that were popular. These structures had a big impact on people’s careers. They helped some people become well-known, while others were only popular for a short time.

Black artists were not passive within these systems. Many people used crossover as a strategy. They did this to reach more people without giving up who they are. Others said no, choosing to be relevant to their community over being accepted more widely. Both options had associated costs.

The 1980s did not solve the problem of whether art is based on its own ideas or on other art. They made it easy to see. Success was never just about popularity. It was about access, framing, and power. Black music had a big influence on the decade’s sound, but there was ongoing disagreement about how it should be celebrated. This showed that there was inequality in the systems that said they were rewarding talent alone.

Roxanne Shanté, Salt-N-Pepa, Janet Jackson: Women Make Noise

Women were involved in every part of hip-hop and modern R&B in the 1980s. But their contributions were rarely given the same respect or lasting impact as those of their male counterparts. Visibility was sometimes prominent, but it was often disconnected from power. This imbalance was recognized early, but rarely corrected.

In the early days of hip-hop, artists like Roxanne Shanté came from a culture of battles, where rappers competed to win the crowd’s attention. These artists used clever lyrics and strong stage presence to make their mark in a scene that valued those who could hold their own in verbal battles. Her success showed that toughness and credibility are not just masculine traits. But the industry that benefited from her work did not offer much long-term support. Contracts were short, stories were simple, and there was less freedom. Women were celebrated when they caused a little trouble, and then they were ignored.

Groups like Salt-N-Pepa were smart about this. They made hip-hop songs that talked about more than just love and romance. They used humor, confidence, and direct language to talk about gender and relationships. Their popularity showed that many people wanted to see their work. But the media often wrote about them in ways that focused on how new and different they were instead of on how well they were made. Women in hip-hop were always expected to prove that they belonged.

In R&B, women faced different pressures. Artists like Janet Jackson worked in environments where production was highly structured. These environments focused on consistency and control. Control became a way of showing independence because people thought they didn’t have it. Jackson’s success required talent, as well as careful negotiation of image, collaboration, and authorship in spaces where decisions were rarely made by women.

In all types of music, women were expected to represent more than just themselves. They were used to represent empowerment, sexuality, or respectability, often at the same time. These roles were often contradictory and exhausting. If they didn’t do what they were told, they might lose support. But if they did everything they were told, they might get fired. People often thought of musical ambition as a kind of calculation, and assertiveness as something difficult.

This imbalance is especially striking because women’s contributions were so important. Their voices, ways of speaking, and stylistic choices helped develop different types of music, influenced fashion and language, and allowed for a wider range of emotions. But historical accounts often only mention these contributions in footnotes or as exceptions.

The 1980s had many talented women in hip-hop and R&B. It didn’t have any structures that were willing to give them lasting authority. Knowing about this gap helps us understand why so many later struggles with credit, control, and representation didn’t just appear out of nowhere. They were already there, but they weren’t obvious. They were part of a decade that celebrated new ideas, but they didn’t give the people who helped create them the same power.

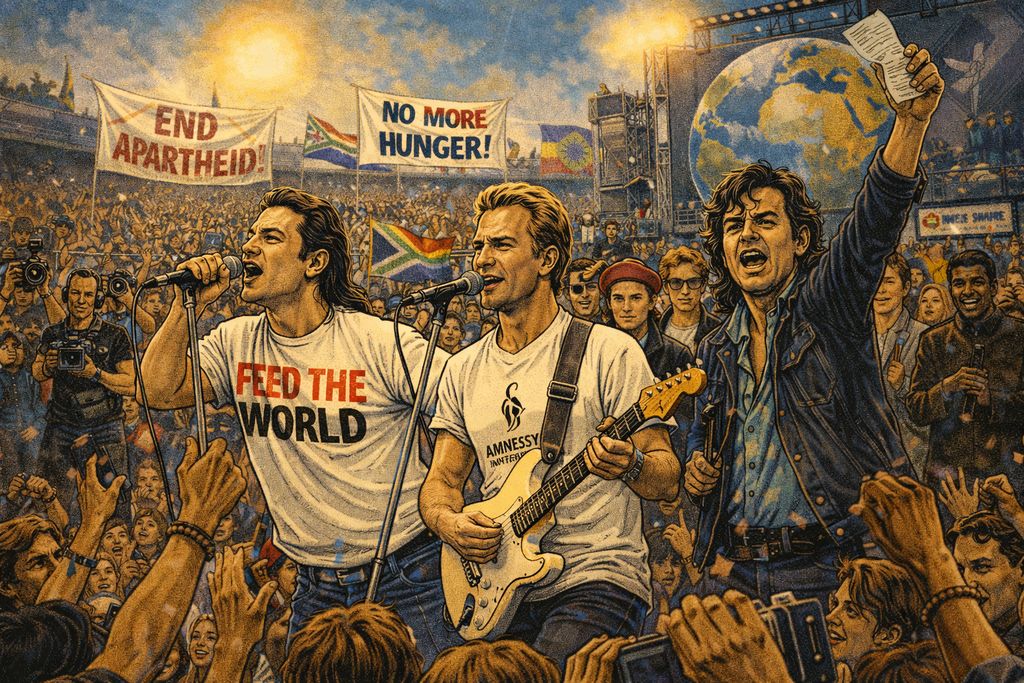

Politics, Protest, and Moral Panic

The 1980s were a time of constant tension. Politicians spoke more strongly, economic disagreements grew worse, and the possibility of a world war did not go away. These pressures weren’t just ideas. They became a part of everyday life, influencing how people thought about the future, safety, and their place in systems that were changing quickly. Music was one of the easiest ways to express, process, and sometimes resist these anxieties.

In the 1980s, political expression was different from what it was in the past. In the past, protest music was loud and clear. In the 1980s, it was more subtle. Fear appeared as a feeling rather than as a clear statement. It was present in the atmosphere, in the way it was repeated, and in the way it was held back. Some artists talked about world problems directly, while others focused on personal worries, questions about spirituality, or emotional distance. Both approaches showed the same main idea: that stability was no longer possible.

At the same time, conservative movements became more powerful, and people started talking more about morality, censorship, and cultural values. Music was in a difficult position. It was seen as entertainment, but it was also seen as a possible threat. This contradiction decided which opinions were supported and which were challenged.

The focus now is on how music expressed unease: how political pressure affected artists, how fear shaped sound and lyrics, and how popular music became both mirror and refuge.

The Cold War Echoes Through Music

The political atmosphere of the 1980s was marked by a resurgence of heated rhetoric about the Cold War. The threat of nuclear weapons was no longer just a distant memory from the past. It was a real and immediate concern that people were talking about in news reports, classrooms, and popular culture. The feeling of unease made its way into music. This happened not only through clear protest, but also through tone, repetition, and holding back emotions. Songs reflected a world where catastrophes felt possible, even normal.

Some artists chose to be more direct. Sting used personal stories to talk about political problems, not just in short, catchy phrases. “Russians” dealt with the fear of nuclear war by talking about how we’re all human and suggesting that fear itself is something we all understand. The song’s calm delivery reinforced its message. The alarm did not need to be loud. It needed to be recognized. This approach was well-liked by listeners who were tired of conflict and didn’t believe grand statements.

In other places, people came together to make their voices heard through protests. U2 combined political awareness with a spiritual and emotional perspective. Songs like “Sunday Bloody Sunday” and other works addressing global conflict didn’t give simple answers. Instead, they focused on feelings of sadness, repetition, and a sense of right and wrong. The music of that generation reflected the knowledge that violence could be a part of the way things are done, not just a one-time event.

In continental Europe, people were often more open about their worries about nuclear energy. Nena’s song “99 Luftballons” used simple pop music to convey the absurdity and fragility of military escalation. The song, which was originally sung in German, used the idea of a misunderstanding getting out of control to talk about a catastrophe. It was a success in many different languages. This showed that these fears were common, even though the political situations were different.

Not all responses were traditional protest songs. Many artists used sound design to express anxiety. The song’s atmosphere was created by its repetitive rhythms, its stark synthesizer lines, and its emotionally distant vocals. Together, these elements created an atmosphere of surveillance and inevitability. These aesthetic choices reflected a world dominated by systems, countdowns, and impersonal authority. People didn’t always talk about their fear, but they felt it.

In the 1980s, protests often avoided taking sides. Earlier movements used music to encourage people to take action. But many artists in that period sounded unsure, tired, and confused about what is right and wrong. This reflected a generation shaped by ongoing tension, not just one crisis. The threat did not go away and then come back. It lingered.

Music became a way to deal with that discomfort. It provided a place for thinking, not for instruction. It revealed political tension that official language could not fully explain. The music of the 1980s Cold War era was not only about urging people to take action. It was also about acknowledging that living under constant threat changes how people listen, think, and feel. This is true even when the worst never happens.

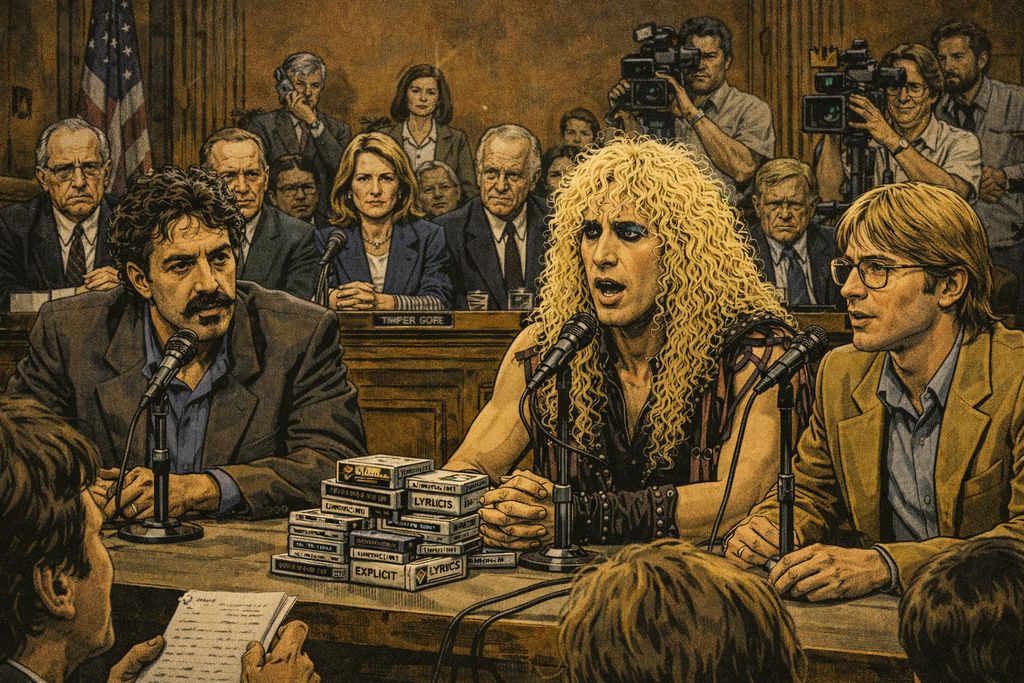

The PMRC and the Battle Over Lyrics

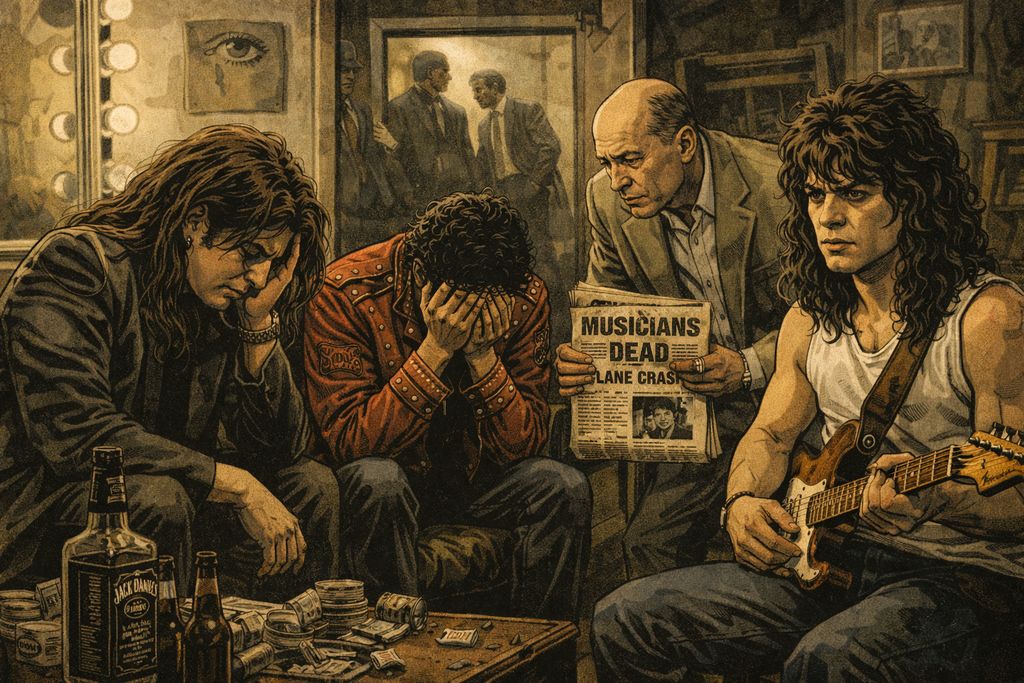

In the 1980s, people were worried about politics and culture. They thought that popular music could be dangerous because it could encourage bad behavior. As youth culture became more visible on television and other global media, it also became a target. Some people say that music can lead to violence, sexual promiscuity, rebellious behavior, and social disorder. These claims were rarely new, but in the 1980s they gained the support of institutions.

In the United States, the most obvious sign of this worry was the creation of the Parents Music Resource Center, also known as the PMRC. The group was led by people with strong political connections. They positioned themselves as protectors of children’s values. They focused their criticism on explicit lyrics and provocative imagery. Hearings in the U.S. Senate put musicians in direct conflict with lawmakers, turning artistic expression into a public debate.