Why the 1990s Still Matter

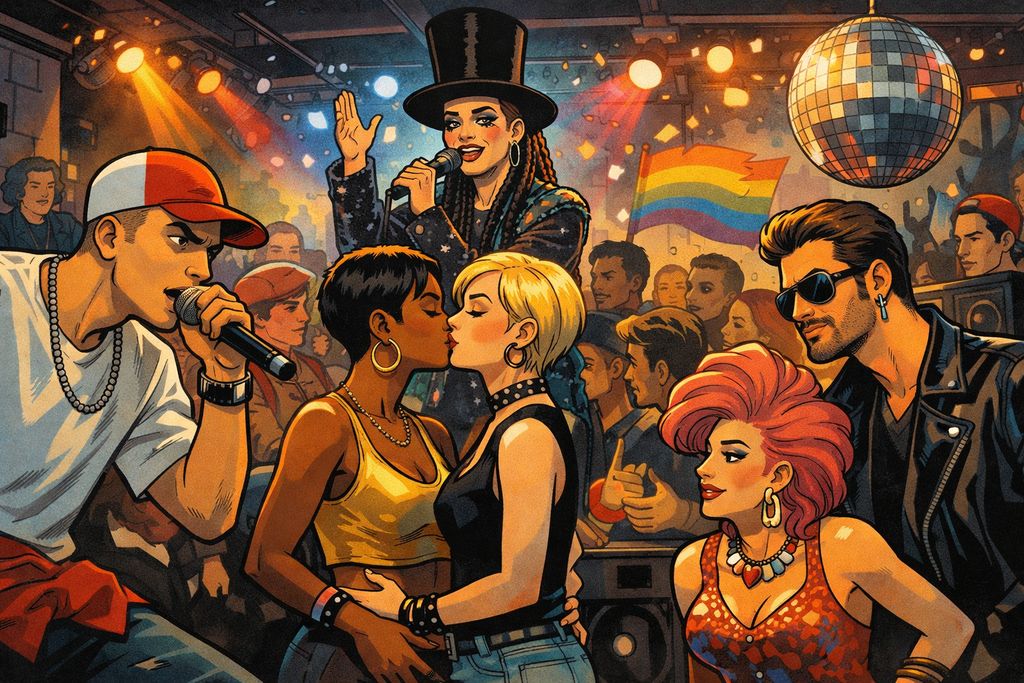

The 1990s were a time when music didn’t have a clear style. Earlier decades were defined by one dominant sound or feeling. In the ’90s, music was more fragmented. Music felt less like a single conversation and more like many conversations happening at once. Many different types of music existed at the same time. These included grunge, hip-hop, pop, electronic music, metal, and singer-songwriter traditions. Each type of music had different fans with different expectations.

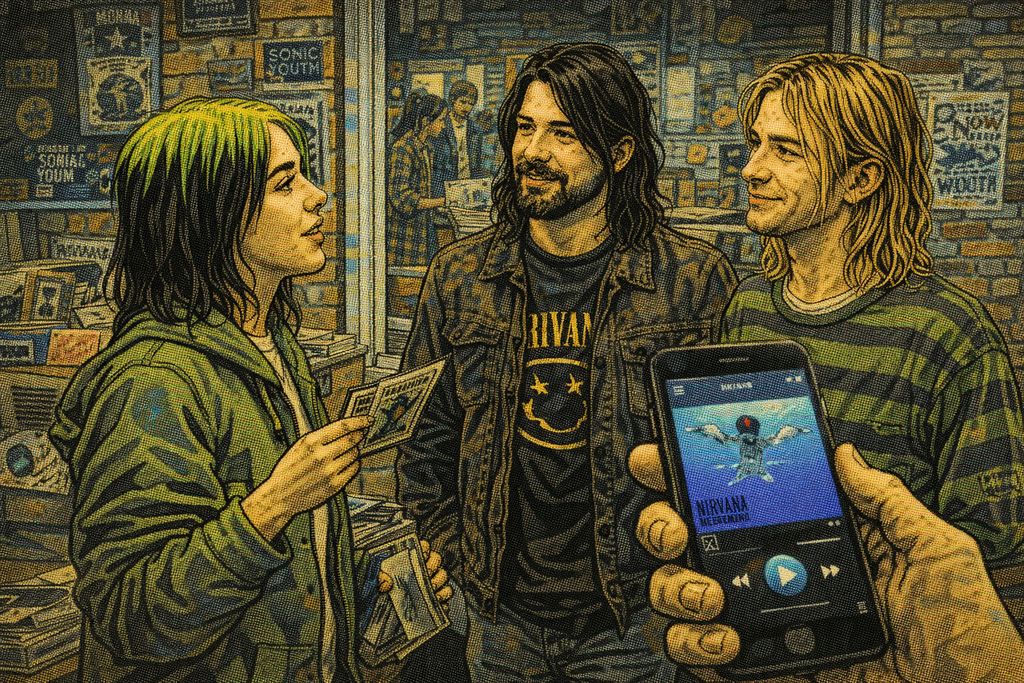

What tied these scenes together wasn’t the style, but the mood. People were starting to feel uncomfortable with the idea of spectacle, and they were doubtful about the simple stories of progress. Instead, they were focusing again on sincerity, even when it was imperfect or unclear. Artists like Nirvana, Tupac Shakur, Madonna, and Radiohead were under different pressures, but they all worked during a time when people didn’t trust simple answers.

This makes the 1990s seem like a time of change rather than resolution. It shows how changes in culture, the music industry, and ideas about what makes music “authentic” have changed what music can be and what listeners expect from it.

No More Dominant Sound: Music Fragments

By the early 1990s, the idea that popular music could have one dominant voice had quietly disappeared. In the past, certain sounds were important to different cultures. Rock and roll in the 1950s, soul and protest music in the late 1960s, disco and punk in the 1970s, and the polished pop spectacle of the 1980s all offered listeners a shared reference point, even when those sounds were contested. The 1990s were a different story.

Instead, the decade began with the idea that it was no longer important to agree on everything. People were divided into smaller groups, media channels were more specialized, and musical styles were more closely tied to personal taste than to a shared experience. Although MTV still existed as a unifying force, its power was beginning to break down as niche programming, regional scenes, and genre-specific press gained influence. The important thing was not whether something was popular with everyone, but whether it felt meaningful to a particular group.

This division was closely related to larger cultural changes. The Cold War had ended, which removed the long-standing ideological framework that had shaped youth culture for decades. While people seemed hopeful about the economy, they were also worried about their jobs, how they would move up in society, and whether institutions like the government were trustworthy. Music helped them deal with these tensions. The lyrics became more introspective, confrontational, or deliberately detached. Sometimes a song was both ironic and sincere.

Rock music is a good example of this. When Nirvana became popular, it wasn’t because they agreed with everyone else, but because they didn’t. Their success did not bring rock audiences together; it showed that they were already divided. Meanwhile, bands like R.E.M. stuck to making albums, while British bands like Blur and Oasis made their national identity a central part of their music instead of just a background element.

Hip-hop followed a similar path. At first, it seemed like everyone in the movement was on the same page. But it became clear that there were differences in opinion, region, politics, and style. The difference between socially conscious rap, street stories, and releases made for more money grew, even as all of them became more popular than ever before.

This lack of consensus was not a failure of the decade. It was the main thing that made it special. In the 1990s, popular music stopped trying to tell one story. In its place, a new landscape emerged where meaning was negotiated locally, emotionally, and often temporarily. Listeners didn’t just listen to music. They used music to set boundaries, explore their identities, and navigate a world that no longer felt neatly organized.

The Industry at Its Peak Power

The music of the 1990s is connected to the industry that created it. Behind the scenes, the decade was a time of growth, confidence, and some imbalance. Major record companies had more power than ever before when the decade began. Compact discs were making money, there were well-established global distribution networks, and music companies were starting to see themselves as cultural institutions instead of risky creative businesses.

The end of the Cold War played a subtle yet significant role in this shift. With old ideological boundaries gone, Western music companies expanded aggressively into new markets. There were more international licensing deals, and English-language pop and rock music became the most popular around the world. Executives like David Geffen and Clive Davis showed that in their time, being an artist and being a businessman were not opposites. Success was measured in terms of cultural impact, size, longevity, and how well the brand was recognized.

At the same time, the industry learned to deal with contradictions. Labels promoted music that seemed rebellious or uncommercial, but they used marketing systems that were becoming more and more similar. Alternative rock, hip-hop, and even underground dance music were made for the general public without losing their oppositional language. This balancing act was financially successful, but it put pressure on artists, who were suddenly asked to be authentic on a large scale.

The media played a key role in keeping this system going. MTV was still the most influential media source of the decade, even though its power was gradually decreasing. Music videos became an important way for musicians to tell their stories. Images, personalities, and visual coherence were as important as sound. Artists who did not fit this pattern were often seen as difficult or uncooperative. On the other hand, artists who adapted were rewarded with more attention and opportunities.

But problems were already starting to show up. Independent labels survived by focusing on a specific scene and not trying to be popular. Artists were more careful when negotiating contracts. Sometimes, artists demanded to have creative control in exchange for ensuring that their work would be successful. The idea of the album as a self-contained artistic statement lasted, but now there was also pressure for singles, videos, and tour-friendly branding.

The most striking aspect of the 1990s industry landscape is not its dominance, but its confidence. It was hard to imagine that the system could fail. Digital disruption was still far off, and the imbalance of power between artists and corporations was mostly seen as a part of being successful. Looking back, this period seems to be a high point. At that time, the music industry seemed stable, even though society was becoming more divided and difficult to control.

The Authenticity Generation

By the mid-1990s, it was clear that young people were no longer looking for traditional heroes. The confident and polished style of the previous decade seemed false to a generation growing up in an uncertain and harsh world. In response, the music played quietly. Big, bold statements became more down-to-earth, showing a side of the artist that was more relatable.

This change is often described as a move toward authenticity, but the meaning of that word changed in the 1990s. Authenticity wasn’t about being a master or having clear morals. It was about exposure. It was about showing uncertainty without resolving it. Artists were respected not for their answers, but for their honesty.

In rock music, this change was clear when many artists said they didn’t like being famous. Kurt Cobain was an example of this contradiction. He didn’t make a big deal out of not wanting to be a rock star; he just acted like it. The media was all over him, and they really put him under the microscope. This message was very relatable to listeners who felt overwhelmed by unchosen expectations.

Hip-hop offered a different but related response. Artists like Tupac Shakur wrote about contradiction, anger, tenderness, and fear in the same song. The result was not a unified political message but rather a portrait of lived complexity. Many listeners liked that this was honest, and felt that it was more real than the positive messages they see in popular culture.

Female artists also changed ideas of sincerity during that time. Musicians like PJ Harvey and Tori Amos worked with intense emotion, without feeling the need to apologize or soften their sound. Their work showed that vulnerability doesn’t have to be passive or reassuring. Instead, being real could be rough, unpleasant, and even confrontational.

What tied these different expressions together was a shared skepticism toward spectacle. In the 1990s, the audience was familiar with media language. They understood performance, branding, and manipulation, even while they were still doing them. This made people a little cynical, but not completely against pop culture. They were careful and cautious about it.

Music became a place where different ideas could exist together. Pain can be shared publicly without becoming inspirational. Success could feel empty. Your identity might not be fully formed. In the 1990s, young people did not demand purity or certainty. They wanted people to recognize it. This had a big impact on the sound of music, how it was written, performed, and received during the decade.

Grunge: The Day the Rock Star Died

When alternative rock became popular in the early 1990s, it wasn’t a smooth change. It entered in an awkward way, bringing the styles of small clubs, independent record labels, and regional music scenes into a media system designed for big shows. What came next was more than just a change in sound. It was also a new way of thinking about what it meant to be a rock star.

People often remember grunge as a sudden change, but it was shaped by years of underground activity and quiet frustration with the excesses of the previous decade. Bands from the Pacific Northwest were more interested in weight, texture, and emotional directness than in technical displays or a glamorous escape. Their music felt heavy, both in volume and atmosphere. Fame came quickly, and many artists felt uneasy about it. That discomfort became a central part of the story instead of just a side detail.

At the same time, alternative rock spread far beyond Seattle. In the United States and the UK, artists changed the meaning of rock music. They made rock music about having doubts, thinking deeply about things, and being confused. Looking more closely at this shift shows how alternative music changed the relationship between artists, audiences, and the industry. It also explains why its short time as a popular culture mainstay left a lasting mark on how rock is understood today.

Seattle Before the World Was Watching

People often say that grunge was an overnight success. However, the scene that emerged from Seattle in the late 1980s and early 1990s developed over time and was not an immediate result of invention. The Pacific Northwest was far from the industry centers where most music business decisions were made. Because of this, it developed its own music scene, with its own clubs, record labels, and other networks. This distance meant bands could experiment without feeling pressure to follow national trends.

Sub Pop was at the center of this ecosystem. The label was started by Bruce Pavitt and Jonathan Poneman, who didn’t set out to create a genre. Instead, they put together a mix of heavy, rough, and emotionally direct bands and presented it to a wider audience. Sub Pop’s visual branding, limited releases, and carefully cultivated sense of place turned Seattle into a narrative as much as a location.

Bands like Soundgarden, Mudhoney, and Alice in Chains all had a similar sound. They all had thick guitar tones, slow tempos, and they all sounded a bit rough. But their differences were also important. Some liked metal, while others liked punk or psychedelic rock. They were united by a shared dislike of excessive theatrics and commercialism.

When Nirvana joined the scene, everything changed. The band’s success did not just make Seattle bands popular. It put them into one category: “grunge.” “Grunge” became a handy short form for describing the style, even though many of the artists associated with it rejected the term.

This process created a myth that still exists today. People usually think of grunge as one big movement with a clear style and way of thinking. The truth is, it was just a temporary combination of local scenes, independent infrastructure, and major-label interest. The roughness that felt real to audiences was partly because they didn’t have a lot of resources, not because they deliberately wanted to be unprofessional.

As major record labels hurried to sign similar bands, the original conditions that had allowed the Seattle music scene to flourish began to disappear. More attention brought money and visibility, but also higher expectations. What had been a local conversation was now being asked to speak for an entire generation. The idea of grunge being powerful came from making things simple. It’s important to understand this tension to know why the movement was so strong but also ended so quickly.

Nirvana: The Voice Kurt Cobain Never Wanted

Nirvana became famous very quickly, which was surprising even to the band. When Nevermind was released in 1991, it wasn’t meant to represent a whole generation. It was meant to be a strong first album for a major record label, building on the underground credibility of Bleach. What happened next surprised almost everyone involved. The album was a big hit, which put the band in a position they weren’t ready for.

For many people, Nirvana became a symbol of refusal. Their songs sounded raw, emotionally direct, and deliberately unpolished. That resistance was quickly turned into meaning. Kurt Cobain was often seen as a spokesperson for disaffected youth, but he was actually very resistant to that role. He seemed uncomfortable during interviews, performances, and public statements. Instead of feeling more at ease with their success, the band seemed more and more uncomfortable.

This tension worsened when the band released In Utero in 1993. The album’s harsh production and confrontational tone were seen as a rejection of mainstream expectations. But even this refusal was accepted by the system it was supposed to criticize. In Utero sold millions of copies, showing that even resistance itself could be sold as a marketable product. For Cobain, this contradiction was not just a thought experiment. It was personal and exhausting.

The media made things more intense. Every time he moved or said something, people tried to figure out what it meant. His political views, struggles with addiction, and relationship with fame were discussed as if they formed a clear story, even when they clearly did not. The complexity of the story was simplified into symbols. The band was no longer allowed to simply exist as musicians. They were expected to represent something larger and to do so consistently.

This expectation had an impact that reached beyond Nirvana. Their success changed what people expected from alternative artists in general. Labels looked for the next band that could have a similar cultural impact, while artists found themselves in an industry that wanted to turn discomfort into a brand. The idea that being real meant looking sad became a dangerous message during that time.

People often tell Nirvana’s story as a tragedy, but this can hide the important details. The band did not just fall apart on its own. They were caught in a moment when the industry wanted to present disaffection as a product and the media was hungry for figures who could represent the general feeling of unease. Nirvana mattered not only because of their music, but also because their rise revealed the limits of representation. Their legacy is closely tied to the question of how much a culture can ask of its artists before the burden becomes too heavy.

Alternative Rock Spreads Far Beyond Seattle

Seattle became known for alternative rock in the early 1990s, but the genre changed in a much broader and more varied way. Even before grunge became popular, alternative rock had already developed different styles in different regions and scenes. The Pacific Northwest’s sudden popularity didn’t cause these movements, but it did change how they were seen. This forced a variety of artists into a single commercial category.

In the United States, bands like R.E.M. were known for longevity and consistency. They were very successful in the late 1980s and early 1990s. This showed that alternative music could be successful without losing complexity or emotional depth. Albums like Out of Time and Automatic for the People focused on melody, reflection, and political unease rather than confrontation. R.E.M.’s influence was subtle but impactful. They helped make it okay for people to think deeply while also being popular.

Across alternative rock, there was a wider range of emotional and musical expression. The Smashing Pumpkins combined loud, rough sounds with soft, fragile sounds. Their albums Siamese Dream and Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness treat personal pain as something big and dramatic rather than strictly private. This approach was very different from the simple style often associated with grunge, but it expressed a lot of the same feelings.

In the UK, alternative rock was different. Bands like Blur and Radiohead addressed questions of national identity, social class, and feeling disconnected from society more directly. Britpop was a reaction to American influence. It combined British pop music with regional accents. Radiohead’s early work, especially The Bends, dealt with feelings of unease and disconnection in a way that fit with alternative rock, even as their sound began to move in a different direction.

These different scenes were connected not by a shared sound but by a shared skepticism of the well-known stories about rock music. The idea of the rock star as a figure of effortless authority felt outdated. New artists came to the forefront, and they focused on doubt, vulnerability, and self-awareness. Success did not make artists feel more secure. In many cases, it made it worse.

As time went on, the term “alternative” itself started to lose clarity. It was used to describe music that was no longer on the edge, but still expressed opposition. This contradiction reflected the broader cultural condition of the 1990s. Alternative rock did not replace mainstream rock. Instead, it took in, questioned, and slowly became a part of it. Alternative rock changed what people thought was possible in rock music and who could be a rock musician.

Women Took Over the 1990s

As alternative rock reshaped mainstream expectations, the 1990s also brought a big change in how women were shown in popular music. This wasn’t because barriers disappeared, but because they were challenged more openly, loudly, and with greater stylistic range than before. Women were no longer limited to just one type of role. They became known for being vocal punks, thoughtful songwriters, experimental pop musicians, and popular chart artists — often all at once and in conflict with the systems that profited from them.

These different paths were united by a growing insistence on authorship. Writing their own songs, creating their own image, and openly discussing desire, anger, trauma, and control became central to their artistic expression. This change was not easy. Female artists were judged more harshly. People looked closely at their emotions and questioned whether they were trustworthy. But the decade made it clear that these expectations weren’t always right.

From the beginnings of punk music to the height of pop stardom, women used the 1990s to redefine power in music. Sometimes that power was loud and everyone could hear it. Other times, it was lonely and open. Across the following chapters, women reshape sound, visibility, and authority, showing why their impact still influences music today.

Riot Grrrl: When Punk Met Feminism

The Riot Grrrl movement didn’t start as a music genre. Instead, it was a reaction to feeling left out, frustrated, and like existing punk scenes were still following the same power structures they said they were against. In the early 1990s, young women across the United States started creating their own networks through small shows, handmade zines, meetings, and local scenes. Music was a key part of this process, but it was also connected to activism, conversation, and community.

Bands like Bikini Kill, Bratmobile, and later Sleater-Kinney, used punk’s rawness as a tool rather than a musical style. Their songs were often short, loud, and to the point. What made them stand out was not how complex their music was. It was the content. The song’s lyrics addressed tough topics like sexual violence, body autonomy, anger, friendship, and survival. The language was direct and didn’t soften itself to be more comfortable or approved by anyone.

People like Kathleen Hanna became famous not because they wanted to be famous, but because they spoke about things that weren’t usually talked about in rock music. On stage, Hanna often invited women and girls to the front of the crowd. This was different from most shows, where male audiences typically dominated the space. This was a practical and symbolic action. Riot grrrl was about changing how people experienced music, not just how it sounded.

Zines were very important. These low-budget publications shared personal stories, political essays, artwork, and show listings, creating an alternative media ecosystem outside of mainstream coverage. Zines let Riot Grrrl participants share their own stories directly instead of having journalists or industry figures interpret them. This demand for people to represent themselves became one of the movement’s most important contributions.

When the media started paying attention, they often treated participants badly or didn’t take them seriously. People often thought of Riot Grrrl as angry, exclusionary, or naïve. This made the group seem like a simple caricature, ignoring the fact that there were many different opinions. In response, many participants stopped doing interviews with the press, which made the movement’s focus seem more inward. This limited how much the public knew, but it also protected the scene from being fully accepted or changed.

Riot grrrl was not based on any specific political ideas or musical styles. It was messy, uneven, and, at times, internally conflicted. Its importance lies not in how well it is made or how long it will last, but in permission. It made room for women to be loud, unfinished, and uncompromising. This changed what people thought about who could use music to speak and how directly they could do so. The effects of that shift extended far beyond the clubs and photocopied pages where the movement first took shape.

Tori, Alanis, PJ Harvey: Anger Without Apology

Along with the combined energy of feminist punk, there was a quieter but just as important change in the 1990s. Women started to express their authority through songwriting. A new generation of singer-songwriters came to the forefront of popular culture. These singer-songwriters were known for their emotional intensity, but they did not use language designed to soften conflict. They saw personal experience as a form of knowledge, not as a confession.

Artists like Tori Amos, Alanis Morissette, and PJ Harvey rejected the idea that being vulnerable should be gentle or reassuring. Amos openly wrote about sexual violence, religion, and power, often using the piano to express these ideas. Her first album, Little Earthquakes, presented pain without offering easy solutions. Instead, she trusted her listeners to deal with the discomfort.

Morissette’s Jagged Little Pill was heard by a huge audience, which is unusual for an artist who is so emotionally direct. The album was a hit, which made people think differently about angry women in pop music. Songs like “You Oughta Know” were often discussed in terms of emotional release or retribution, but their real impact lay in how unapologetically they claimed public space. Morissette did not make her voice sound more reasonable. She let anger, confusion, and vulnerability exist together, and her audience did the same.

PJ Harvey approached authority from a different angle. Her work did not have a clear autobiographical style. She used different characters and strong images to explore desire, violence, and power. Albums like Rid of Me and To Bring You My Love were more difficult to understand. They required listeners to be more involved and less passive. Harvey’s presence made people think that being emotionally honest has to be literal. It could also be dramatic, unpredictable, and intentionally left open-ended.

What these artists had in common wasn’t their style, but their ability to control their work. They wrote their own songs, created their own sound, and came to define their public identities in a way that felt authentic to them. This was important in an industry that often used female emotions to sell products instead of considering them as a creative force. These musicians insisted on being the ones to write the songs, which made emotional expression seem like a way to show authority instead of openness.

This change had a big impact on culture. It changed how audiences listened and how critics evaluated sincerity. People stopped seeing emotional openness as a weakness that needed to be hidden. It became a form of strength. The 1990s singer-songwriter movement did not promise healing or closure. Instead, it offered recognition. For many listeners, this made them see music in a new way.

Madonna, Janet, Björk: Masters of Reinvention

While alternative scenes and singer-songwriter traditions changed ideas of intimacy and authorship, the 1990s also saw a big change in mainstream pop music. This change was mostly driven by women who understood how to make themselves seen better than anyone else. In this decade, being a popular female singer wasn’t just about being present. It was about control, negotiation, and strategic reinvention within an industry that still assumed women were interchangeable or disposable.

No artist showed this better than Madonna. By the 1990s, she was already a well-known figure around the world. But instead of making her image more stable, she made it deliberately unstable. Projects like Erotica and Sex confronted public discomfort head-on, blurring the lines between provocation, critique, and self-authorship. The reaction was immediate and intense, but it showed that there are still very limited ways for women to express themselves. Madonna’s determination to be in charge of her own story turned a source of disagreement into a way to make her voice heard, even if it meant losing some personal and business opportunities.

At the same time, Janet Jackson showed a different way of using power. Her work in the early and mid-1990s combined technical precision with emotional openness. Albums like Rhythm Nation 1814 and janet. talked about sexuality, vulnerability, and social responsibility without making them seem like they were opposites. Jackson worked with producers Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis. Together, they created music that was both personal and grand. This made her not just a passive performer, but a central creative force.

In other places, artists like Björk pushed the boundaries of pop music. Björk, who grew up listening to alternative and electronic music, saw pop as a flexible genre, not a set style. Albums like Debut and Post combined new ideas with accessibility, combining emotional expression with musical risk. Her visibility made space for other artists who did not fit the conventional pop narrative of femininity or restraint.

What these figures had in common wasn’t their genre, but their strategy. Each one had to deal with a system that required constant exposure but offered little protection. They used reinvention, collaboration, and deliberate ambiguity to maintain creative agency. In this case, being a star was not a reward. It was a challenging terrain to navigate.

The power dynamic around female pop stars in the 1990s reflected this new approach. These artists showed that becoming popular did not mean being neutral or following the rules of art. They could take control of the situation in public, even when being watched closely. This helped expand the range of what women could express in popular music and how seriously their expression could be taken.

Hip-Hop Takes the Throne

At the same time, hip-hop went from being on the edge of popular culture to being at the center of it. What started out as a regional or subcultural form became one of the most influential musical languages of the decade. This change brought money, popularity, and new ideas, but it also created new pressures and problems that changed the culture from within.

When hip-hop became popular, people expected it to play many different roles at once. It was expected to stay true to itself while reaching a wide audience, speak for real experiences while following commercial formats, and represent communities without being reduced to stereotypes. Artists dealt with these expectations in very different ways. Some people used their music to share political or social messages. Others focused on personal stories, regional identity, or new ways of writing music. None of these paths were without tension.

The most important people of the decade, including Public Enemy, Nas, and Tupac Shakur, worked in a world that was changing quickly. Major record labels, more media coverage, and more public scrutiny all played a role in this change. From there, hip-hop had to balance growth with responsibility, and its discussions about power, representation, and consequences came to define not only the genre but also the broader cultural conversation of the 1990s.

The Golden Age Goes Mainstream

By the early 1990s, hip-hop already had its own history. The genre’s Golden Age set high standards for artistic excellence, focusing on the poet’s ability to write beautifully, to speak up about social issues, and to come up with new ideas. Groups and artists who became popular in the late 1980s showed that rap can be intellectually demanding, focused on politics, and musically innovative. The challenge of the new decade was not invention, but growth.

Artists like A Tribe Called Quest approached this moment with a sense of balance. Albums like The Low End Theory mixed jazz-influenced production with lyrics that were easy to talk about. They showed a type of hip-hop that felt relaxed but also thought-out. Their work suggested that growth didn’t need to be impressive. Even as the audience grew, subtlety could travel just as far.

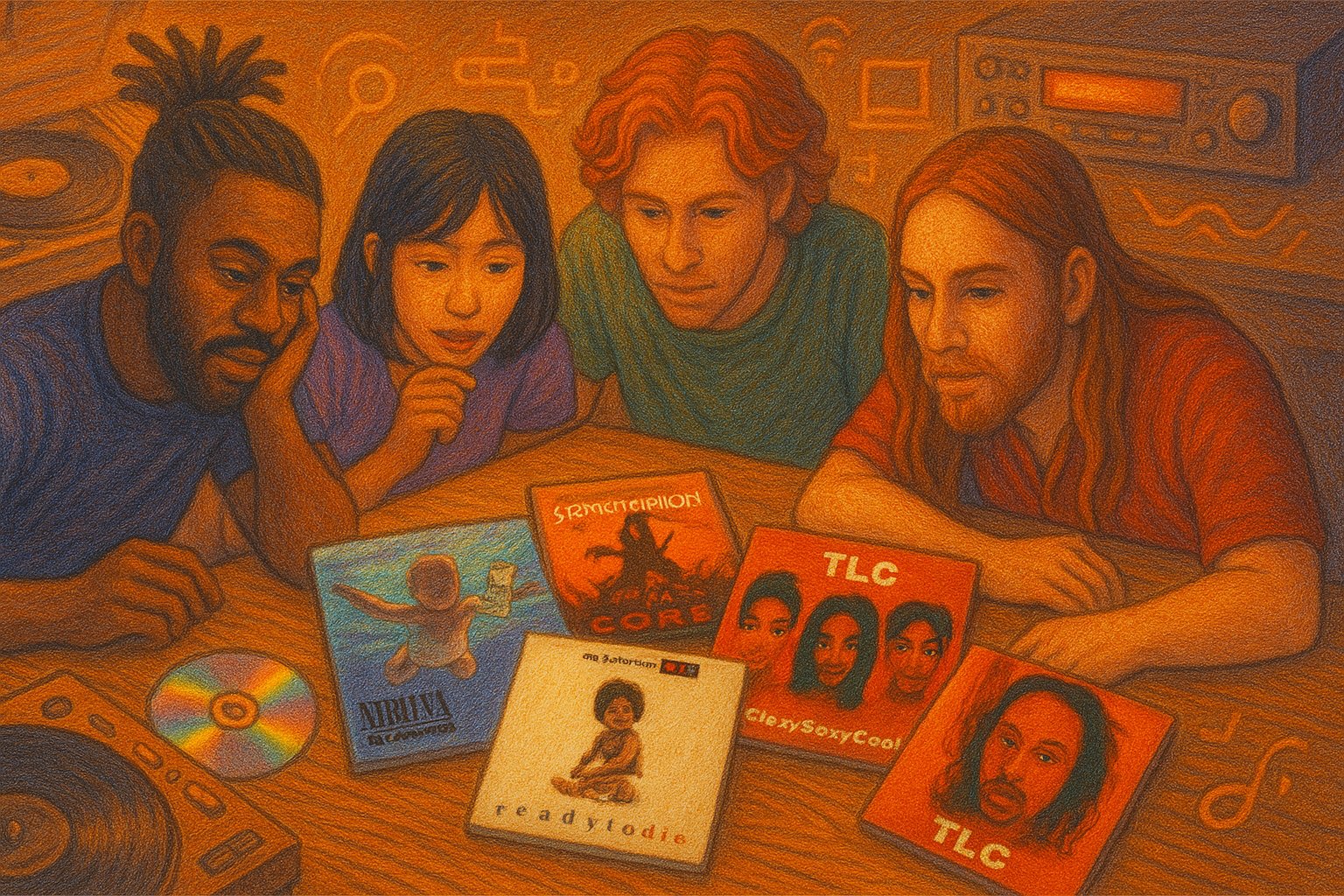

For Nas, expansion took a more focused form. Illmatic, released in 1994, wasn’t made to be a hit on the radio; yet, it became an important text. The stories about life in Queensbridge were very specific, and this made them strong. Instead of making general statements, Nas used specific examples, voices, and moments. He trusted that being precise would make his work convincing. The album’s impact wasn’t just about how many copies it sold. It also changed what people thought about what a song lyric should be like.

At the same time, the business side of hip-hop was changing quickly. Major record companies started investing more money in rap music because they saw its cultural and financial potential. This investment increased production and distribution, but it also created new challenges. Singles were prioritized. Visual branding became more important. Success was measured by how well songs did on the charts and how much people trusted them.

Public Enemy showed the tension of this change. Their earlier work made them seem like political activists who were very vocal in their opposition to established power structures. But as hip-hop’s audience grew, it became harder to keep that confrontational style in the mainstream. People wanted to see radical images without thinking about the message. Many asked whether hip-hop could stay political, and if so, how much of that politics would be allowed.

The transition from the Golden Age to the Billboard charts was not a simple story of compromise. Many artists used their new platforms to make their message clearer. But the shift changed the rules of participation. Hip-hop was no longer just for itself. It was for a wider audience that often listened without considering the personal experiences behind the music.

This change set the tone for the rest of the decade. Hip-hop’s rise was obvious, but it came with problems. As the genre gained popularity, new questions about responsibility, representation, and visibility arose.

East vs. West: When Rivalry Turned Tragic

As hip-hop’s audience grew in the mid-1990s, regional differences became one of its most visible divisions. There were always differences between scenes, but now they were made bigger by the national media, major record labels, and an industry that wanted simple stories. Local debates were presented as disagreements between two sides, with the East Coast and West Coast positioned as rivals rather than two similar traditions.

On the West Coast, artists like Tupac Shakur brought strong feelings and disagreements about politics to the forefront. Tupac’s music showed a range of feelings, from being vulnerable to being aggressive, and from being empathetic to being angry. Albums like Me Against the World and All Eyez on Me showed a worldview shaped by unfair treatment, personal problems, and constant public attention. He drew intense attention because of this. Many saw him as a symbol, but they didn’t pay attention to how complicated his work was or the contradictions he was open about.

On the East Coast, The Notorious B.I.G. had a different point of view. His storytelling was full of details, rhythm, and a sense of humor about ambition and consequences. Ready to Die showed that success is often linked to risk, loss, and doing things that are morally wrong. Biggie’s appeal wasn’t in being a “good guy”; it was in his clear storytelling. He made the mechanics of survival visible, even when they were uncomfortable.

The competition between these musicians was driven more by the environment around the music than by the music itself. Magazines, radio stations, and television outlets made regional differences seem like personal conflicts, rewarding provocateurs with attention. Labels benefited from increased visibility, and artists felt pressure to show their loyalty in public. Nuance had a hard time surviving in an environment that favored spectacle.

People often forget that there were many artists who didn’t fit into this simple category. West Coast hip-hop was never just one type of music, just as East Coast rap included many different styles and political ideas. But the media just made it seem like there was only opposition. The result was a cycle where reality was shaped by perception and symbolic conflict had real consequences.

The deaths of Tupac Shakur and The Notorious B.I.G. were some of the most painful moments in hip-hop history. They are often used as cautionary tales, but this framing risks obscuring the structural forces at work. These were not just random tragedies caused by people’s personal decisions. They were made bigger by an industry that made it hard to tell the difference between representation and exploitation, and by a media culture that treated conflict as content.

This time made hip-hop think about how visible it was. The genre had become a part of popular culture, but this change came with some problems. People’s pride in their region turned into a competition. Personal expression became a symbolic burden. The East Coast–West Coast story showed how quickly things could be made simple when culture is seen through systems that like drama more than understanding.

Lauryn Hill, Missy Elliott, Queen Latifah: Breaking the Boys' Club

Hip-hop became more popular and successful during the 1990s. As this music genre grew in cultural and commercial power, women artists encountered a familiar contradiction. Their visibility increased, but their authority did not always follow. Female MCs were often invited into the spotlight as exceptions rather than central contributors. They were celebrated for breaking barriers while navigating an industry structured around male dominance. Their work was important for two reasons. First, they shared a message that people needed to hear. Second, they created a space where people could gather and share ideas.

Queen Latifah was one of the first people to directly challenge these limits. Her music combined social criticism with confidence, rejecting the idea that strength required aggression or detachment. Songs like “U.N.I.T.Y.” addressed misogyny without using shock tactics. Instead, they showed respect as a basic human right, not as a way to make a moral point. Latifah’s success showed that hip-hop could include feminist ideas without losing its credibility or popularity.

For Lauryn Hill, authority took a more inward path. Her work with the Fugees and her solo album, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, combined rapping and singing in new ways that added more emotional depth to the genre. Hill’s writing often focused on important questions like who we are, what we believe, and our self-worth. The album was a huge success, but it also made people focus a lot on her. Expectations grew quickly, and there was less room for experimentation just as her influence reached its peak.

Missy Elliott used a different approach. She started doing hip-hop at the end of the 1990s. She did it in a funny way, with strange images, and she was willing to change how music and pictures looked and sounded. Her work with Timbaland used rhythms and textures that felt strange, and her videos did not follow traditional ideas of what it means to be a woman. Missy’s presence showed that power could come from being playful and not giving in, not just from fighting.

Even with these breakthroughs, there were still some structural limitations. Female artists were often seen as representing all women in hip-hop, a responsibility that was rarely given to their male counterparts. The support they provide might not always be reliable, and they might not always recognize important things in a consistent way. Success stories were seen as rare exceptions, not signs of big-system change.

Women had a big impact on 1990s hip-hop. They were successful and helped the genre grow. They introduced new ways of talking about respect, intimacy, joy, and doubt. Their work showed that hip-hop artists don’t have to sound or look a certain way to be respected.

But by the end of the 1990s, women were still not equally represented in the hip-hop industry. But they changed the subject. They made it impossible to imagine the future of rap without them. This laid the foundation for the style of music that would continue to influence the genre well after the 1990s, even though they did not receive much recognition until much later.

Pop and R&B: Emotion Meets Industry

While hip-hop was expanding rapidly, pop and R&B became the most popular types of music in the world. These genres were defined not only by sound or style, but also by infrastructure. Groups of songwriters, producers working together, international studios, and release schedules all influenced how music was shared and how success was measured. The songs’ catchy hooks and emotional depth were the result of increasingly complex systems behind the scenes.

This didn’t mean that the music lacked feeling or meaning. In fact, the decade produced some of the most emotionally powerful and commercially successful pop and R&B records in history. Artists like Mariah Carey, TLC, and Boyz II Men addressed intimacy, vulnerability, and desire directly, even as their work was shared through industry channels that were highly managed.

At the same time, the 1990s marked a shift toward international pop production. Scandinavian studios, European dance influences, and collaborations between countries quietly changed mainstream music. In this context, pop and R&B found a balance between emotional connection and large-scale production. This shift also raised questions of authorship, control, and identity in genres that are often seen as purely commercial.

Producers Become Stars: The Architects of Pop

One of the biggest changes in 1990s pop and R&B happened mostly behind the scenes. The people who make music changed over time. First, the power was in the hands of individual performers. Then, it moved to producers, songwriting teams, and studios that could make hits. This did not eliminate artistry, but it did change how creative authority was used and how success was achieved.

In the United States, Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis’s partnership is an example of this. For example, their work with Janet Jackson showed how a consistent production team could help shape an artist’s long-term identity instead of just chasing singles. Albums like Janet. and The Velvet Rope were both commercially focused and emotionally rich. They showed that being organized didn’t have to make music feel empty.

Across the Atlantic, a different but equally influential system was taking shape. In Stockholm, producers like Denniz Pop and his apprentice Max Martin developed a songwriting approach that treated pop music as a universal language. They focused on melody, structure, and emotional immediacy, which allowed their songs to be popular all over the world. The most important thing was not where an artist came from, but whether the song could communicate instantly.

This approach quietly changed the economics of pop music. Songs became more flexible, able to be changed and moved around. An artist could use an existing framework instead of building one from the beginning. This gave some performers a faster path to visibility. But for others, it raised questions about authorship and replaceability. The systems that made pop global also made it easier for record labels to treat artists as interchangeable parts.

R&B music was particularly affected by these changes. While the genre had always had producers and writers, this became even more common in the 1990s. Artists like Mariah Carey had more and more control over the production of their music, even as the number of people involved in making a song grew. Her transition from singing slow love songs to faster, more danceable music showed her ability to make her own choices and the changing logic of the music business.

It’s important to understand that the producer era did not strip music of personality. Instead, it gave the responsibility to the people who were already doing the work. Emotion was still a part of it, but it was carefully put together, tested, and improved. Hooks were designed to stay in place. Choruses were meant to feel inevitable. This precision was no accident. It was the result of knowing a lot about how audiences listened, remembered, and responded.

By the end of the decade, these systems had become the foundation of popular music. They made music travel faster and farther than ever before. However, they also reduced the amount of uncertainty. The producer era is known for its influence on the sound of the 1990s, using organization to enhance feelings instead of suppressing them. That organization’s impact on popular music is still felt today. It affects how music is made, marketed, and understood.

R&B's Perfect Balance: Soul Meets Modern

R&B was in a unique position in the 1990s. It was both personal and commercial. It had deep roots in the long tradition of Black musical expression and played a central role in the global music industry. Many R&B singers learned to combine intimacy and scale in their music. The result was a body of work that felt emotionally immediate even as it moved through highly professionalized systems.

Mariah Carey is a good example of this. She first became famous for her beautiful singing voice and love songs. However, as the decade went on, her music started to include hip-hop rhythms, modern production techniques, and more obvious expressions of desire. Albums like Music Box and Daydream showed how she was starting to feel more confident about being multifaceted. Carey was more than just a singer. She started writing and arranging more and more songs, showing her creative control in an industry that often underestimated her.

Groups like Boyz II Men brought new life to the genre. Their music was a mix of gospel and classic soul, and they performed like a professional pop band from the 1990s. Songs like “End of the Road” and “I’ll Make Love to You” were very sentimental. They showed emotional vulnerability at a time when cynicism was common in other genres. Their success showed that if you perform with confidence, you can still get a lot of people’s attention.

TLC made things more complicated. Their music combined playful confidence with direct engagement on topics such as safe sex, financial independence, and self-worth. Albums like CrazySexyCool and FanMail combined accessibility with social commentary, often mixing the two. TLC’s public image suggested freedom and ease, but their struggles with contracts and financial control revealed the limits of that image.

Toward the end of the decade, R&B started to become more reflective and introspective. Lauryn Hill’s album The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill was a big moment in this change. The album mixed R&B, hip-hop, and soul music, and it was successful because it was honest and emotional. Its impact was twofold: it increased sales and awards, and it changed the way people thought about vulnerability.

The 1990s were a time when rhythm and blues (R&B) music was defined by its mix of emotion and professionalism. The genre did not suggest that emotions were separate from business. Instead, it asked whether emotional truth could survive within it. For most of the 1990s, it looked like the answer was yes. But that delicate balance became more difficult to maintain in the years that followed. Even so, it still has a big impact on how intimacy and ambition are shown in popular music.

Teen Pop Takes Over the World

By the late 1990s, pop music had become one of the most popular types of music in the music industry. People often say that this music is superficial or manufactured, but it was actually designed to respond to a specific cultural moment. Teen pop was not about being spontaneous. Instead, it offered a version of relatability that was controlled. This version balanced innocence, ambition, and emotional accessibility. These qualities appealed to parents, record labels, and advertisers.

Artists like Britney Spears became famous through a system that closely controlled how they were seen, their music, and their stories. Her first album, …Baby One More Time, showed that being a teenager was all about intense emotions, not about being complicated. Her feelings of desire, confusion, and longing were expressed through polished hooks and familiar structures, allowing young listeners to recognize themselves without feeling overwhelmed. What looked easy was actually the result of a lot of planning.

Groups like the Backstreet Boys and the Spice Girls made this model popular around the world. The Backstreet Boys focused on harmony, emotion, and working well together. They built on earlier boy-band traditions and adapted them to the production values of the late 1990s. The Spice Girls, on the other hand, made individuality a big part of their brand. They used different personas and the language of “girl power” to brand themselves as empowered. This resonated globally, even though it oversimplified feminist ideas.

What made teen pop particularly interesting was its relationship to authenticity. People often criticized these artists for not having enough depth or control over their work. But many of them dealt with a lot of criticism and high expectations when they were young. In this case, authenticity had more to do with performance than with authorship. The music asked listeners to believe in emotional sincerity while accepting industrial construction as a given.

Behind the scenes, the systems described earlier in the decade were fully operational. Teams worked together to create a consistent experience across music videos, tours, and media appearances. These teams included songwriting teams, choreographers, image consultants, and marketing divisions. This integration allowed Teen Pop to dominate the global charts but also made it hard for other songs to stand out. Mistakes, aging, or visible discomfort were seen as problems rather than natural parts of life.

Teen pop was successful, but it also showed both what had been achieved and what problems might come in the future. It showed how emotions could be shared and spread quickly. But it also made people wonder if it was sustainable, if it was fair, and if it cost too much too soon. Many artists who came up through this system later spoke openly about feeling burned out and losing control.

Instead of dismissing teen pop as trivial, it is more useful to see it as a mirror of its time. It reflected a time when people were more comfortable with the idea that being real could be created, controlled, and sold. This comfort would soon be tested, but in the late 1990s, teen pop was one of the clearest expressions of how far the industry had learned to shape feelings.

Heavy Music's Crisis of Identity

Away from chart-focused pop, heavy music in the 1990s did not disappear; it had to face some hard truths. Metal and hard rock didn’t just disappear after the ’80s. They had to deal with changing cultural expectations, changing ideas of what it means to be a man, and a public that was more and more doubtful of things that were just for show. This led to a period of tension, change, and sometimes retreat.

Many critics did not like traditional metal, calling it outdated or emotionally empty. But the genre still had a large fan base. At the same time, younger listeners were turning to music that expressed frustration, vulnerability, and feeling disconnected more openly. In response, heavy music started to incorporate new influences, dropped showy elements, and focused more on emotional depth than technical complexity.

Metallica, Nine Inch Nails, and Tool used heaviness not as a way to show off their power but as a way to explore control, pain, and identity. People still showed signs of aggression, but they usually directed it towards themselves instead of others.

The argument here is that heavy music became a space where masculinity was questioned rather than affirmed. In this space, anger coexisted with fragility, and emotional exposure replaced heroic distance. This lets us see how the 1990s changed heavy music’s sound, feelings, and cultural impact.

Metal Adapts or Fades Away

In the early 1990s, metal was already popular. The genre had been very popular in arenas and on television in the previous decade. However, it had become too rigid in its style, and now it seemed outdated. People started to doubt the ideas of being talented, showing more than was necessary, and acting in a masculine way. This was true for critics and younger listeners, who did not identify with these ideas anymore. Metal didn’t just disappear. It recalibrated.

For bands like Metallica, it was important and necessary to change their style of music. Their 1991 album, which is also called The Black Album, had simpler song structures, tighter production, and a focus on weight over speed. The change led to accusations of betrayal from some people in the metal community. However, it also showed a larger truth. Metallica was responding to a cultural climate that favored being direct and showing emotion more than being technical. The album was a hit, showing that metal could change without losing its intensity.

Other bands took different paths. Megadeth kept focusing on being precise and complex, but their sound got smoother over time. This made it hard to tell if they were aggressive or easy to listen to. Meanwhile, groups like Pantera made music that was very intense and physical. Vulgar Display of Power did not use fancy language. It showed anger as something real and immediate, not something made up. This approach was popular with people who felt disconnected from both traditional optimism and alternative irony.

In countries outside the United States, the metal music scene grew stronger and more popular, even though it didn’t get as much media attention. The band Sepultura used three things in their work: groove, tribal rhythms, and political awareness. They did this especially on albums like Chaos A.D. Their music showed the realities of global inequality and cultural mixes. It went against the idea that metal was a strictly Western or apolitical form.

Not all responses involved a complete change. Some bands chose to leave. Faced with fewer fans tuning in to the radio and changing tastes, some parts of the metal world moved away from mainstream culture. Instead, they focused on their own subcultures, where they kept their own style and didn’t worry about being popular. This withdrawal made it harder for most people to see what was happening, but it also protected the different types of metal. Scenes became more divided, more focused on local issues, and often more intense.

These paths were connected by their shared experience of change. Metal could no longer rely on being impressive. It had to show why it was important emotionally and culturally in a world that was questioning traditional authority. In the 1990s, metal music went through some big changes. Bands started to think about their own style more, either by making it simpler or by trying new things. Sometimes, they even stopped making music altogether. Because of this, the genre survived a time that many thought would be its end. Instead of falling apart, metal found new uses that had to do with power, authenticity, and durability.

Alternative Metal: Heavy Music Looks Inward

As traditional metal music tried to come to terms with its past, a new type of heavy music emerged. This new style was all about being emotionally open and honest. Alternative metal wasn’t against heavy music, but it asked what heavy music could express. These artists didn’t show strength as control. They used distortion, repetition, and volume to explore feelings like anxiety, obsession, and vulnerability. The result was music that seemed to be focused on itself. Sometimes, it even made the listener feel a bit uncomfortable. It was not easy to understand.

Nine Inch Nails played a key role in this change. Trent Reznor was the creative force behind the project, which blended industrial textures with confessional songwriting. In other words, it combined personal pain with public performance. Albums like The Downward Spiral show self-destruction as a process, not as a spectacle. The music did not provide a traditional kind of emotional release. Instead, it lingered, causing discomfort. This forced listeners to deal with the fact that the pain was still there, instead of the pain going away.

Tool’s approach to emotional exposure was characterized by control and restraint. Their music was complex, intentional, and often hard to understand, drawing listeners into long, changing structures that mirrored emotional tension. The lyrics talked about power, spirituality, and self-awareness without offering any moral advice. Albums like Ænima showed that heavy music can be a form of confrontation, not just release. The intensity came from focus rather than excess.

For bands like Faith No More, changing genres became a way to push back against the industry. They were willing to switch from metal to funk to pop to experimental noise, which was unexpected and made people question what was “serious” and what was “coherent.” Mike Patton’s singing style changed quickly, going from being aggressive to being ironic and then vulnerable. This showed that a masculine voice could take many different forms and still feel credible.

Deftones introduced a different emotional range. Their work combined weight with a sense of place, desire, and uncertainty. Albums like Around the Fur suggested that aggression and intimacy are not opposites. They are actually connected. This blend of styles attracted listeners who felt disconnected from both traditional metal’s aggressive behavior and alternative rock’s distant attitude.

Alternative metal was different because it wasn’t just about being new for its own sake. These artists used heaviness as a way to express inner struggles rather than outer victories. Masculinity was no longer seen as a matter of certainty or dominance. It looked more uncertain, wounded, and searching.

This approach did not replace traditional metal, nor did it aim to. It made a space that was similar to the real world where people could be emotional in ways that didn’t have to be explained. Alternative metal made it possible to express more ideas through heavy music. It showed that intensity can be quiet, controlled, or unresolved. That growth would influence the emotional language of heavy music for many years, even after the term “alternative” had become unclear.

Nu Metal: The Genre Critics Loved to Hate

By the late 1990s, heavy music had reached a point where its internal tension was visible to a mass audience. Nu metal came about when different styles, frustrations, and social realities came together. Many critics had a hard time taking this new style seriously. It was very successful in the business world, but many people thought it was rude, old-fashioned, or just in it for itself. That reaction shows that people are uncomfortable with the culture as well as the music.

The band Korn made heavy music more emotional. They made it more vulnerable, raw, and unresolved. Their early albums were influenced by personal struggles, using low-pitched guitars and constant, repeating rhythms to create a sense of being trapped. Jonathan Davis’s lyrics were not meant to be metaphorical or distant. They were honest, sometimes painfully direct, and that lack of mediation connected with listeners who felt left out of more ironic or intellectual scenes.

Limp Bizkit was a different kind of rap metal band. Their combination of metal, hip-hop, and confrontational performance tapped into feelings of resentment and defiance. People often dismissed these feelings as tasteless or juvenile. Even so, the band’s popularity showed that something was true. Nu metal was popular with working-class audiences and suburban youth. These young people felt that cultural gatekeepers were mocking them and that their voices were not being heard in stories about progress.

Toward the end of the decade, Linkin Park began to change how people thought about nu metal. Their first album, Hybrid Theory, combined aggression with introspection. They used emotional struggle to show that it is something shared, not just something that opposes you. The band’s focus on themes like inner struggles, self-questioning, and relationships made their music more emotionally resonant, even as it maintained a commercial appeal.

Nu metal became a point of contention because of its sound and its refusal to fit neatly into existing cultural hierarchies. It mixed different types of art, didn’t care what critics thought, and was honest about pain without using fancy language. Many listeners liked how honest it felt. Many critics felt threatened by it.

People did not like nu metal. They did not take it seriously. The genre was seen as a waste of time, and its audience was thought of as uneducated or old-fashioned. But people didn’t consider the reasons why this criticism was happening. Nu metal came about because of economic uncertainty, social division, and the feeling that earlier promises of authenticity had become new forms of exclusion.

Nu metal didn’t offer any solutions. It offered recognition. It didn’t have many emotional words, but it still had a strong effect. The genre showed how questions about social class, masculinity, and whether something is acceptable still strongly influenced musical judgments at the end of the 1990s. By doing this, it ended the decade by reminding listeners that heaviness was about more than just sound. It was about who felt listened to, and who didn’t.

Electronic Music's Quiet Revolution

In the 1990s, rock, pop, and hip-hop dominated the public conversation. But another kind of music was growing, one that didn’t fit the usual rules of the music business. Electronic music spread through clubs, warehouses, temporary spaces, and informal networks. This affected how people experienced music instead of how they talked about it. For many listeners, the connection to this music wasn’t based on the artists’ identities or personal stories. Instead, it was about the feeling of nights, the energy of movements, and the shared physical experiences.

Dance culture in the 1990s offered something that other types of music and art increasingly struggled to provide: a way for people to be completely immersed in a shared experience. DJs, producers, and club organizers cared more about the music and the vibe than about having famous guests. Records were tools, not statements. The experience was more important than the author’s name, and being anonymous was usually seen as a benefit.

At the same time, this underground growth made people suspicious. News stories often talked about electronic music in a negative way, using words like “drugs,” “panic,” and “losing control.” Legislators responded by imposing restrictions that did not fully understand the music and the communities associated with it. But the culture continued, changing in secret and spreading around the world.

From here, the story turns to how electronic music changed listening habits, social spaces, and ideas of authorship during the 1990s. It treats clubs, DJs, and scenes as more than just side stories. It sees them as central forces that transformed how music was a part of everyday life. They often didn’t ask for recognition.

Club Culture: The Nights That Changed Everything

The beginnings of electronic dance music (EDM) in the 1990s happened earlier, but it was during this decade that it became a part of everyday life for millions of people. House and techno music are more than just genres. They were systems of gathering people, moving people, and spending time together. These systems were built around clubs rather than charts and around DJs rather than stars.

In Chicago, house music started in Black and queer club spaces in the 1980s. People like Frankie Knuckles helped create a sound designed for long nights and emotional release. By the 1990s, house music had become popular all over the world, but it still had the same basic ideas: repetition, groove, and a shared experience. The music was simply practical. It was created to bring people together on the dance floor, not to be studied on its own.

Detroit techno followed a different but similar path. Artists like Juan Atkins, Derrick May, and Kevin Saunderson described their work as futurist, but it was based on the economic and social realities of post-industrial Detroit. The music’s exact precision and controlled emotion reflected a city shaped by technology, loss, and strength. Technology did not create a reality that was separate from the real world. It made it abstract.

In Europe, especially in cities like Berlin, London, and Manchester, these sounds were used in new ways. Clubs became places where different cultures came together. They were influenced by punk, post-industrial art, and local youth cultures. After the Berlin Wall fell, the city had many abandoned buildings and offered some temporary freedoms. This allowed techno music and social experiments to thrive. DJs like Jeff Mills brought Detroit’s intensity to these spaces, showing that techno is more about mindset than about location.

What made club culture in the 1990s stand out was its connection to time. Club music is different from music that is played on the radio. Club music grows and changes over time. The tracks blended into one another, creating long, continuous lines instead of separate points. This structure encouraged a different kind of listening. It made people focus more on being present and paying attention than on analyzing or thinking too much. The DJ’s job wasn’t to perform, but to guide the event. The authority came from sensitivity, not visibility.

These scenes weren’t perfect. Access was inconsistent, and commercialization followed quickly once it became popular. However, the most important aspects of house and techno music offered a different approach from the decade’s growing focus on image and storytelling. In the club, it’s hard to tell who’s who. Rhythm was more important than language. For many people, this was not an escape from reality; it was a way of changing reality.

By the end of the 1990s, electronic club culture had changed how people experienced music forever. It showed that meaning didn’t need a face, a story, or a fixed song. Sometimes it became clear through repetition, bodies in motion, and the shared understanding that what mattered was happening right now, together.

The DJ as Curator: When Anonymity Meant Power

One of the most radical aspects of 1990s electronic music culture was how it changed the idea of authorship. In recent decades, dance music has been more focused on personality, branding, and visibility. DJs were a key part of the experience, but they often kept their names secret or didn’t want to be the focus. They gained their authority not because people recognized them, but because they gained people’s trust over time on the dance floor.

In club culture, DJs weren’t expected to perform the way they do today. There was no set list of songs that had to be followed, and no spotlight that demanded constant attention. Instead, DJs sense the mood of the room and change the speed of the music, the feel of the music, and how intense the music is based on the energy of the room. The goal was to keep going, not to reach a high point. This approach went against the idea that music needed a main character for it to feel meaningful. Who played a track wasn’t as important as how well it was received.

This anonymity was not an accident. Many DJs didn’t like the trappings of celebrity, thinking that being visible was a distraction from the communal nature of the experience. Vinyl records were tools that were mixed and layered in ways that made it hard to know who made them. The origin of a track was often less important than its role in a larger context. In this situation, ego wasn’t completely eliminated, but it was intentionally made less important.

People like Jeff Mills were an example of this way of thinking. Mills is known for his technical precision and intensity. He focused more on sound and movement than on his personal image. He put on a show that was more about the energy and movement than about showing off. Many house and techno DJs also created a presence that felt like it was leading the audience, rather than bossing them around.

The focus on shared experiences was in contrast to the broader culture of the 1990s, where music videos, magazine covers, and award shows focused on individual stardom. Music had different rules in clubs and warehouses. The dance floor was a temporary community where people came together based on the same rhythm and movements. It wasn’t a place for sharing stories or defining who we were. Even though they were different in terms of background, language, and status, they were still able to connect and engage with each other.

At the same time, this culture was facing its own problems. As electronic music became more popular, some DJs became very famous, and big events showed who was the best. It became harder to maintain a balance between being anonymous and being recognized. Even though the scene became more commercial, its core values remained the same. Smaller clubs, local nights, and underground parties continued to prioritize a cool vibe over a big show.

The impact of 1990s DJ culture can be seen in this alternative way of understanding music. It suggested that music could be powerful without being personal, and communal without being didactic. In a time full of division and self-awareness, the dance floor was a special place where your presence was more important than how you danced. It wasn’t about being seen or understood. The most important thing was to be there with each other for as long as the music lasted.

Rave Culture vs. the Authorities

As electronic music and rave culture spread throughout the 1990s, people paid attention to them in a similar way. What started as local events focused on music and movement was seen more and more as a social problem. News stories often focused more on fear than on sound or community. They painted raves as places of excess, danger, and moral collapse. This framing didn’t just appear out of thin air. It repeated older worries about young people, drugs, and how people act in groups. But now, it’s presented to a new generation in a new way.

In the UK and Europe, newspapers and TV reports often showed dance events as wild parties where people lose control. The music was described in vague, dehumanizing terms. It was repetitive, mechanical, and threatening. This language was important. By taking away the background and purpose of electronic music, coverage made it simpler to see entire genres as issues to be solved instead of cultures to be understood.

People’s reactions to the situation were political and came soon after. A turning point in the UK was the 1994 Criminal Justice and Public Order Act. The language used in the gatherings focused on “repetitive beats,” a phrase so broad that it showed how little the legislators understood about the culture they sought to regulate. The law gave the police more power to shut down events and move crowds around. This meant that some types of musical experiences were now considered crimes. The act was presented as a response to public safety concerns, but it also showed that some people were uncomfortable with youth autonomy and non-commercial organizations.

The same kind of situation happened in other places too. In some places in Europe and North America, authorities paid more attention to clubs and other places where people meet. They often connect electronic music with drug use, but they don’t consider the bigger social issues. This selective focus was striking. Other types of music have long histories of substance use, but electronic music was singled out as uniquely threatening. This was partly because it didn’t fit into the traditional categories of music authorship and performance hierarchies.

For many people involved in the scene, this negative reaction made them more aware of the importance of having their own organization. Events became less obvious, locations less permanent, and networks more able to withstand challenges. Instead of giving in to pressure, dance culture found a way to adapt. The fact that people were able to remain anonymous and that the group as a whole was responsible made it difficult to dismantle it from the outside. People shared information with each other, and information was shared through trusted channels. This helped people feel connected to each other, even though fewer people were around.

The panic about electronic music showed that people are afraid of losing control. Dance culture made people think differently about how people should gather, how music should be enjoyed, and who should be allowed to lead large groups without the approval of an organization. The fear was not just about noise or drugs. It was about independence, about bodies moving together without a clear leader or message.

By the late 1990s, electronic music had overcome these challenges and become more deeply part of global culture. Clubs reopened in new forms, festivals adapted, and electronic sounds started to be used in mainstream pop and advertising. But people still remembered the negative reactions. It reminded us that when a culture changes, people often resist because they’re used to things being a certain way. The moral panic of the 1990s was more about our society’s limits on tolerance than about electronic music. In the 1990s, we were still learning to live with fragmentation and freedom.

Global Sounds: Music Beyond the Anglo-American Center

As scenes became more connected, the story of 1990s music was still often told from American and British perspectives, but that framing doesn’t capture how the decade transformed popular music around the world. In the 1990s, regions outside of the Anglo-American center started to make their own connections with international markets. These connections were based on their own histories, audiences, and priorities. They weren’t just imitations of what was already happening in the international markets.

This change happened for a number of reasons. The spread of satellite television and the growing presence of international music labels made it easier for music to travel across borders. At the same time, local communities were starting to feel more confident about who they were. Artists no longer felt they had to remove elements like language, accents, or cultural references from their work just to be heard. Instead, they embraced them.

From Latin America to Europe and some parts of Asia, the 1990s saw the creation of pop, rock, and dance music that spoke directly to local realities while also engaging with global sounds. These scenes weren’t just on the edges of the decade. They influenced its rhythms, look, and business strategies in ways that would only become fully clear in the years that came after.

What follows looks at 1990s music that was not centered on one style. It traces regional infrastructures, language choices, and the mix of sounds that emerged when global influences met local forms of expression. In doing so, it changes how we see the decade: not as a Western story, but as a shared, uneven, and deeply connected musical moment.

Latin Pop Before the Crossover Moment

Before Latin pop became a big commercial force in the late 1990s and early 2000s, it was already doing well on its own. Latin pop music’s global reach didn’t originate in the 1990s, but the decade laid the groundwork for it. The 1990s saw the strengthening of regional music industries, an expansion of touring circuits, and a reaffirmation of the value of Spanish-language music. This was a time when English-language music dominated international charts.

In Latin America, artists were building careers that didn’t depend on being recognized in the United States. Bands like Soda Stereo played in stadiums all over the continent. They mixed rock music with pop music and used local cultural references. Their success showed that you can be popular and successful without having to compromise your language. The music spoke directly to its audience. It reflected urban life, political uncertainty, and generational change. It also felt immediate and grounded.

Singer-songwriters like Caetano Veloso kept changing during the decade. They did this by adapting old traditions to new situations. In the 1990s, Veloso’s work combined thoughtful reflection with exploration, incorporating international styles while staying connected to the rich tradition of Brazilian music. His presence reminded listeners that it’s possible to keep things the same while also making improvements. He showed that a region’s unique qualities can be a positive thing that can help you grow.

Shakira was a young singer when she released her album Pies Descalzos in Colombia. The album combined rock instruments with Latin rhythms and personal songs. Her early work was very popular among Spanish-speaking audiences, even before she started performing in English. The most important things were emotional clarity and cultural specificity, not polish or universality. Shakira’s success showed how Latin pop music could grow in a natural way. It could first become popular in its home country and then gain more international attention.

The infrastructure supporting these artists was crucial. Regional labels, radio networks, and television programs like music countdown shows helped make artists well-known. When people toured across national borders within Latin America, they created shared cultural circuits. These circuits did not rely on validation from Anglo-American markets. These systems let artists build strong relationships with fans over time. This is better than trying to become famous quickly in other countries.

The most important thing about this period is that it takes time. In the 1990s, Latin pop music became stronger, more polished, and more successful. When crossover moments finally happened, they weren’t sudden discoveries. Instead, they were delayed recognitions of work that had already shown how popular it was.

Knowing Latin pop before the crossover boom makes us question the idea that global success starts in the center and spreads out. In the 1990s, a lot of the most exciting music happened in other places. It was supported by local audiences who didn’t need translation to see themselves in the music they loved.

Europe's Pop Renaissance: From Britpop to Eurodance

In the 1990s, people in Europe started to feel more confident about their local pop cultures. They were also more interested in highlighting their national identities instead of making them less obvious. This change was influenced by political developments, especially after the Cold War, and by growing media networks that allowed regional events to spread beyond their borders while maintaining their unique character.

In the UK, pop music became a way for people to express their culture. Britpop was created as a response to American dominance. However, it also had a deeper significance. It openly addressed issues of class, place, and everyday life. Bands like Blur embraced regional accents and social observations. They saw Britishness not as something to be nostalgic about, but as something experienced in real life. Their work was very different from the more common language of stadium rock. They showed that being specific could be a good thing.