Why the 2000s Still Confuse Us

People often have a hard time describing the music of the 2000s with one sound or image. This is not a sign of weak memory. It is one of the central truths of the decade. The 2000s were a period without one clear style or shared sound. Older structures were breaking down, while no stable new system had fully replaced them.

At the start of the decade, the music industry still seemed strong. CDs were selling well, pop stars were on television and radio a lot, and they were still popular. But the situation was less stable than it looked. Digital files moved faster than contracts. Listeners learned to search, skip, copy, and collect. Artists entered a world where they were more visible, but not more protected.

The music of the 2000s reflects this tension. It tries to do too much and doesn’t quite succeed. It is polished but restless, personal but sometimes overexposed. Genres often blended, but rarely replaced one another completely. Careers could rise quickly and fall just as fast. Many of the decade’s most important records sound like artists trying to orient themselves while the ground shifts beneath them.

To understand the music of the 2000s, you don’t need to look for one particular style. Instead, focus on the transition itself: uncertainty, experimentation, and long-term change.

When the Party Ended: The 90s Hangover

The music of the 2000s did not suddenly change. It arrived at a time when the late 1990s still shaped expectations. In those final years, confidence was high, business was expanding, and many people believed culture was moving steadily forward. The end of the 20th century felt celebratory. Pop was commercially dominant, alternative rock had passed its peak, and electronic sounds were moving further into the mainstream. Even as rules were tested, they still seemed broadly understood.

But that did not last long. At the start of the 2000s, many people felt that something important was changing, even if they weren’t sure what yet. Outside of music, people were worried about politics, the economy, and global security. In the music world, these pressures led to feelings of unease rather than immediate changes in style. Artists were still releasing records the same way they always had, but people no longer trusted the assumptions behind those channels.

One of the most important things about this time was that people were not sure about authority. Record labels still controlled how music was distributed, but they were losing that control. Music television was still important, but its cultural influence was decreasing. Even though they didn’t understand how much it would change how people listened to music, audiences felt like it was becoming easier to access music. The result was a strange mix of old confidence and new doubt. The music from the early 2000s often sounds polished, expensive, and like it was produced by a professional. At the same time, it seems to show signs of restlessness and emotional tension.

This uncertainty also affected how artists presented themselves. Many performers entered the decade with high hopes, influenced by the success of the 1990s. The idea of a long-term career was still around, but it was becoming harder to keep up. New artists felt pressure to succeed right away. At the same time, well-known artists felt the need to change, but didn’t have any clear instructions on how to do that.

The early 2000s were not defined by a single movement or genre. Instead, they revealed themselves through their atmosphere. Songs became more introspective or defensive. People started to pay more attention to images and control, even though the systems that were supposed to enforce that control were starting to fail. The cultural mood shifted from being about arrival to being about adjustment. Music didn’t know what was going to happen next, but it knew it had to change.

The Old Industry's Last Stand

At the start of the 2000s, the music industry still believed in its long-term success. From the outside, it looked strong and sure of itself. Major record companies controlled most of the music markets around the world. They sold many records and generated significant revenue. Success was defined in simple, familiar terms. A system that had worked for decades was built on platinum albums, chart positions, radio rotation, and music television exposure. Few people in the industry expected a sudden collapse.

The compact disc was still the most important source of money for popular music. Albums cost a lot, production budgets were big, and promotional campaigns were carefully planned. Radio programmers decided which songs would be played on the radio for a large audience. Music videos on TV played a big role in how people saw and remembered artists. This infrastructure rewarded companies that were big and predictable. It was better for artists who could be put together, promoted, and used in different ways on different media.

But this system needed control, and it was already losing that control. The idea that music spread slowly and expensively was the basis for manufacturing, distribution, and access. Consumers were expected to buy whole albums, even if they only wanted one song. Information moved from the labels to the listeners, not the other way around. By the year 2000, these assumptions were no longer accurate, even though they were still used to manage contracts and people’s careers.

The industry’s internal culture also had an impact. The people in charge were very careful when making decisions. People were only willing to take risks if there was a good reason to do so, based on what had happened in the past. This made the system strong but not flexible. When small changes first appeared, people often didn’t take them seriously. They thought they were just small problems, not a big warning. People thought that file sharing, home recording software, and online fan communities were just small, temporary problems, not big, long-lasting threats.

Artists were caught in the middle of this contradiction. They had the resources to produce at scale and reach large audiences around the world. On the other hand, they were starting to rely more on systems that required constant visibility and commercial success. Although there was some creative freedom, it was strictly controlled. People quickly built careers, but when things slowed down, they quickly abandoned those careers.

Looking back, the industry at the start of the 2000s is like a building that’s still standing but has already been emptied out. It kept its language, rituals, and social structures the same. It couldn’t imagine a future that was different from its past.

A Decade Without a Center

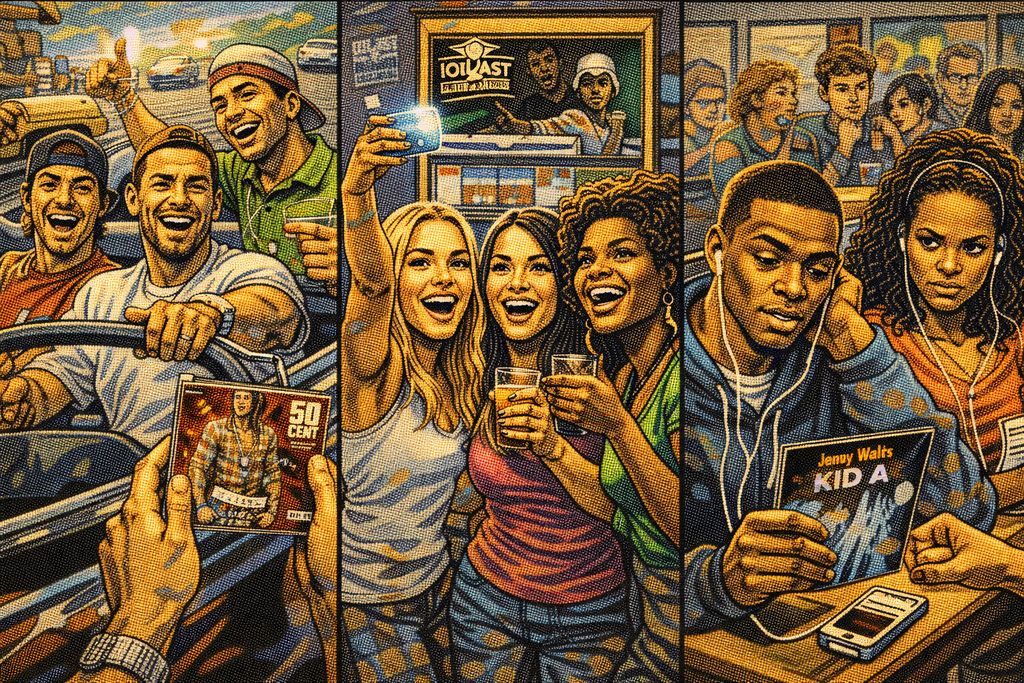

The 2000s are different from earlier musical eras, not because there is less creativity, but because there is no central focus. In the past, even when there was diversity, dominant movements and widely recognized narratives provided direction. The 2000s were different: many parallel developments happened at once, but they did not merge into one clear story.

At first, this was not immediately obvious. Even then, music still seemed to move in the same ways it always had. Pop stars were the most popular, hip-hop was becoming more popular, rock bands played in more places, and electronic music continued to grow. However, none of these currents fully defined the decade. Rock music was the most popular genre in the 1970s, while hip-hop was the most popular in the 1990s. Rock and hip-hop were both very influential in their respective decades. Influence is now based on the situation, not on general rules.

Part of the shift came from the way people were using the internet. People no longer had to use the same sources to discover music. Some people found music through radio and television. Others found music through file sharing, forums, blogs, or personal recommendations. These paths rarely crossed. Two people living in the same city can have very different musical tastes without knowing it. Even though more people had access, shared standards were becoming less clear.

Artists responded in different ways. Some people wanted to be seen by as many people as possible. They wanted to be the most popular. Some people chose to focus on specific groups of people. They were willing to have a smaller audience if it meant having more freedom. Many people felt unsure about which path to choose because they weren’t sure which one would make them happy. This made careers less stable. Success can come on suddenly and then go away just as quickly. Often, it’s hard to explain why.

This lack of a center also changed how music was discussed. Critics, fans, and industry professionals had a hard time agreeing on what was most important. There are more and more lists, genres, and hierarchies, but people are less and less in agreement. Instead of one conversation, there were many overlapping conversations. Each conversation was valid within its own context, but each one was limited in scope.

The 2000s were not chaotic because artists lacked direction. They were unsettled because the structures that once aligned taste, exposure, and meaning were no longer able to do so. Music was still important to people who looked for it. The idea that everyone was listening to the same thing at the same time for the same reasons changed.

The Digital Revolution Arrives

The story of music in the 2000s must include technology. This was the decade when people’s access to, sharing of, and valuation of music changed more quickly than the institutions designed to manage those changes. The result was a rough transition. There was conflict, confusion, and quick adaptation.

For many years, the music industry had a system that controlled access to music. Songs moved through clearly defined channels. They went from labels to radio stations and from stores to listeners. Technology changed this situation, not by making sound quality better or adding new instruments, but by making things easier. Music became simpler and easier to copy. A song can travel the world without permission, payment, or context.

The shift caused strong reactions. Artists, record companies, and lawmakers said that digital sharing was like stealing and destroying culture. Listeners, on the other hand, often saw it as a way to be free and have access to things. Both of these views were influenced by fear. One group was afraid they would lose money and power. The other feared being left out of culture because of cost and scarcity.

This led to a 10-year fight over who owned it, how valuable it was, and who had the power. Old gatekeepers tried to defend their role, while new ones quietly took their place. This change permanently altered the relationship between artists and audiences. Music became less protected, more personal, and more unstable. That change still affects how music is made and listened to today.

Napster: The Day Music Broke Free

When Napster first appeared in 1999, it didn’t seem like a game-changing innovation. It seemed useful. Users could search for songs, download them in minutes, and save them to their personal collections without leaving home. This felt obvious and unavoidable to listeners, especially younger ones. Music had become data, and data wanted to move freely.

The music industry was shocked by this. Napster went around every existing form of control. There were no record stores, prices, or contracts involved in the exchange. Users shared songs without packaging, liner notes, or extra commercial framing. A product turned into a file. The industry reacted with fear instead of curiosity.

Well-known artists got involved in the conflict. Metallica was the band that was against Napster the most. They filed lawsuits and said that file sharing was theft. Dr. Dre did the same thing. These responses were understandable from a legal standpoint, but they were harmful from a cultural perspective. Many fans saw them as attacks on listeners instead of defenses of labor. The debate quickly became very intense, with people on different sides, even though the reality was more complicated.

The music industry did not realize that Napster did not make people want free music. It showed a desire that was already there. CDs cost a lot of money, and only a few people could buy them. They were mostly sold in wealthy markets around the world. When file sharing made things easy to share, it showed that the old way of thinking about value was wrong. The law saw music as something owned, but listeners saw it as something everyone should be able to enjoy.

After Napster was shut down by lawsuits in July 2001, it had 26.4 million users worldwide. That was its peak. Immediately after, other options appeared. LimeWire, Kazaa, eDonkey, and BitTorrent networks replaced it, often with fewer safety measures and less oversight. The attempt to stop piracy was more like a game of chase than a real solution. Each shutdown showed that control could no longer be enforced in the old way.

The panic was not only about the economy. It was also about big ideas. The industry had become known for controlling who could listen to what and when. File sharing went against that authority. By the early 2000s, it was clear that even if piracy could be reduced, the idea of completely controlling access was already outdated. The decade would go on with that loss still affecting it.

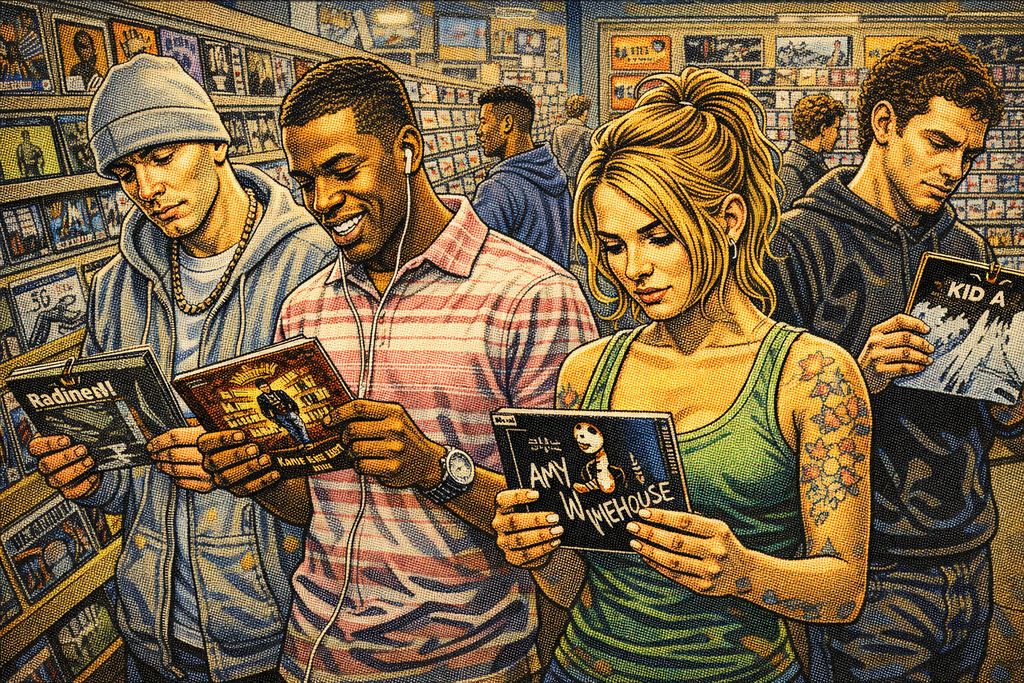

The MP3: When Songs Became Files

Napster showed that the industry was weak, but MP3 files quietly changed how people thought about music. Compressed audio files changed how people listened to music more than any other factor, including platforms and lawsuits. Music was no longer connected to a specific object or fixed sequence. It became easy to move and rearrange, and people could carry it with them.

The MP3 was not about sound quality. In many cases, it sounded worse than a CD. Songs were usually encoded at 128 kbit/s, but the quality got better over time. For example, Apple made all iTunes tracks better in 2009. They increased the bit rate to 256 kbit/s. This was when they launched iTunes Plus. MP3s offered people freedom. The files were small enough to store a lot of them, easy to transfer, and compatible with more and more devices. A person’s music collection could suddenly include thousands of songs instead of a few shelves of albums. This scale changed how people behaved. People started listening to music not in terms of albums, but in terms of individual tracks.

The shift made the album less meaningful. For many years, albums were the main way that artists told stories and that audiences engaged with their work. Even when listeners liked individual songs, the album still organized them in a certain way, using things like the order they were listed in, cover art, and overall context. The MP3 removed much of that background structure. Songs spread on their own, detached from where they were first created. A song can become popular even if people have not heard the whole album.

Listening software made this change even stronger. Programs like Winamp let you shuffle and create playlists, and organize your music into different categories. Music libraries started to reflect what each person liked instead of a mix chosen by someone else. Two people could own the same song for two different reasons. One person might have found the song by chance, while the other might have been searching for a specific genre. Meaning became personal and separate.

Artists and record labels had a hard time responding. Some people still thought that albums were the most important thing, and they hoped that listeners would go back to listening to music in the traditional way. Some people liked singles more than albums. They thought of albums as a group of songs, not as a complete body of work. You can hear this tension throughout the decade. Many records start with their best songs because they know that listeners may not pay attention past the first few tracks.

The way music is sold has also changed how people feel about it. Songs are easier to love and easier to discard when they are taken out of their original context. People’s favorite things change more quickly. People’s loyalties change from artists to specific moments, moods, or memories. Music is still important, but it’s not as clear how it fits into our lives over time.

By the mid-2000s, the MP3 had become the new normal for listening. Even people who bought CDs often converted them into digital files and stopped using CDs. The album wasn’t gone, but it was no longer the default. It survived because of people’s intentions, not because of its physical structure.

iTunes: Apple Tames the Chaos

When Apple created the iTunes Store in 2003, many people thought it would fix the disorganization of the digital music industry. For the first time, there was a legal, centralized platform that offered individual songs at a clear price. The price of 99 cents per track seemed reasonable, fair, and modern. The music industry was in disarray, but iTunes offered a way to fix things without going back to the way things were before.

The appeal of iTunes was that it was easy to find and buy music. Listeners could buy only the songs they wanted without having to pay for full albums. Instead of letting people share digital files for free, labels could make money by selling them. Artists finally had a fair way to share their work online. They didn’t have to resort to lawsuits or debates about what was right or wrong. It looked like things were back to normal for a second.

But this sense of control was mostly just an illusion. Although iTunes replaced some illegal downloading, it did not change the underlying habits that file sharing had created. Listeners were already used to immediate access, large libraries, and choosing how they engaged with music. Buying a song did not make the album more popular, and it did not stop people from listening to music in different ways. iTunes made fragmentation official in many ways.

The platform also made new hierarchies stronger. Songs were more important than albums. Charts started to show downloads instead of how many people were engaging with the content. A track’s success might not be related to its artistic context. This made it easier for artists who could produce immediate, stand-alone hits, and it made it harder for artists whose work depended on long-form storytelling or subtle development.

For the music industry, iTunes delayed a major challenge instead of avoiding it. The money made from selling digital products never fully replaced the money made from selling physical products. What was most important was that control over distribution changed. Apple, not the labels, owned the storefront, customer data, and listening environment. The gatekeeper had changed shape, not disappeared.

Artists felt this change in small ways. Digital success could be measured, but it was also becoming more and more unpredictable. A song could become popular very quickly and then disappear from the charts. It became harder to plan a career, and easier to mess it up. There was more visibility, but not more stability.

Looking back, iTunes was not a return to order. It was a bridge between eras. It turned the idea of owning things into a digital form and got people ready for a future where owning things would be optional. The industry agreed to the deal because it needed time. People accepted it because it was easier. They didn’t realize that the balance would only be temporary.

The Death of the Album

As digital listening became the norm, the album entered a strange and uncertain phase. Even though it was still the main way artists released music, it didn’t define how people experienced that music. Every day, people were skipping tracks, rearranging songs, and extracting favorites. In the past, people thought that linear listening was just something that happened automatically. Now, it requires effort and intention.

That shift directly impacted how albums were made. Artists and producers realized that a lot of listeners might not make it to the middle or final tracks. Records often started with the songs that were easiest for people to access. Hooks arrived faster. Ballads and experiments were moved to the end. The way albums were set up changed from stories to having an especially strong opening. This wasn’t a failure of creativity. It was a response to new conditions.

Some artists did not like this change. Green Day’s 2004 album American Idiot was a deliberate attempt to make the album feel like a whole package. The record had a lot of connected songs, common themes, and political ideas. It asked listeners to stay, follow, and commit. The record was a big success. It showed that long-form storytelling was still possible. But it also showed how exceptional these efforts had become. Albums had to show why they existed.

Others adapted more quietly. Eminem released songs that were suitable for radio airplay and for his most dedicated fans. Beyoncé’s early solo work had strong, stand-alone songs and was carefully arranged to evoke strong emotions, even though many listeners only engaged with some of it. In each case, the album survived, but people had different expectations.

The rise of skipping also changed the emotional connection to music. When listeners can choose the order and length of songs, they become a way to create a certain mood instead of being part of a bigger story. A track can mean a lot in one moment and then not mean anything the next. This flexibility is great, but it can also make people impatient. Albums that take a long time to play or need a lot of attention might be misunderstood or forgotten.

It’s important to note that the shift away from traditional radio listening didn’t happen because people stopped respecting artists. It came from abundance. When there is more access than there is time or attention for, selection becomes unavoidable. Skipping is not rejection. It is navigation.

By the late 2000s, the album was no longer protected by format or habit. It still had meaning, but only when artists and listeners decided to see it that way. This change did not ruin the album. It just changed the conditions it needed to survive.

Loud and Louder: Music Gets Aggressive

The 2000s changed the sound of music in ways that were hard to predict. Digital production tools made recording easier, but they also created new pressures. Music was now competing in places other than the radio or record stores. At the time, it was competing with headphones, computer speakers, and compressed files. These files were often played back at inconsistent quality and volume.

In response to these conditions, producers and engineers emphasized immediacy. The songs were mixed to sound loud, full, and clear, even when played at low volumes or on low-quality devices. Sometimes, subtlety was not as important as having a strong impact. This wasn’t just a choice based on looks. It was also a practical response to the places where people were listening to music. If a song didn’t stand out right away, people would skip it.

At the same time, digital tools allowed for more creative options. The process of sampling, editing, and vocal processing became more precise and visible. The studio started to function as its own instrument. Producers became well-known creative forces. They were able to shape the emotional and sonic identity of entire eras.

The sound of the 2000s shows the tension between how creative something can be and the pressure to be immediate. It is polished, compressed, and often direct. It shows the effects of trying to adapt its voice to a world that was listening differently than before.

The Loudness War: When Everything Got Compressed

One of the most noticeable yet poorly understood features of music from the 2000s is how loud it is. This wasn’t just a coincidence or a matter of personal preference. It was the result of a competition among recording studios to make recordings louder and more immediate than ever before. This competition is known as the “loudness war.”

As music started to be played more often on digital devices, songs were judged more often in places where the conditions were not always the same. You can hear a track through things like cheap earbuds, laptop speakers, or burned mix CDs played in cars. Producers and labels were worried that quieter recordings would sound weak or be overshadowed by more aggressive mixes. To prevent that, they reduced the range of sound levels. The softer moments were made louder, the loud parts were made quieter, and the volume was made louder overall. The goal was to be present no matter what.

For a while, this approach worked. Loud songs grabbed attention quickly. They sounded strong on the radio and consistent across devices. But it came at an emotional cost. Compression removes contrast, and contrast is what makes a scene exciting. When everything is loud, it doesn’t feel as big as it could. Many recordings from the 2000s have a constant intensity. This intensity is a reflection of the cultural pressures of that time. These recordings sound urgent, crowded, and slightly anxious, even when the material itself is calm or reflective.

The loudness war affected almost every type of music. Pop records were mixed for immediate impact. Rock albums were known for their density and aggression. Hip-hop and R&B had a lot of dense, forward-facing production, with elements that were close together. Electronic music, which is already built around repetition and energy, often became even more forceful. This wasn’t a mistake made during the process of making it. Engineers were doing exactly what the market wanted.

Some artists and producers were upset about this. Albums that preserved dynamics (the loudness and softness of sound) stood out for their warmth and depth, even if they sounded quieter. Over time, people who listened started to feel tired because the music was always loud. The songs blended together. After a while, listening for a long time was tiring.

By the end of the decade, more people outside of technical groups knew about the loudness war. Critics and fans wondered if the album was too loud and lacked subtlety. This conversation did not immediately change the situation, but it did create an important idea. The sound was not impartial. It reflected the pressures of its time.

The emotion of 2000s music is intense, and it tells a subtle story. It talks about competition, things that distract people, and the fear of being ignored. Music was the way people tried to express themselves and be heard in all places. It absorbed the stress of the environments it was a part of.

Auto-Tune: The Sound of Digital Emotion

Autotune is an example of a production tool that has had a big impact on the emotional language of 2000s music. It was originally designed as a corrective technology, but it quickly became something else. By the start of the next decade, its presence was obvious, and it had begun to represent the connection between human expression and digital technology.

The change often mentioned as the start of this shift actually happened earlier, with Cher’s 1998 hit “Believe.” By the early 2000s, that sound was no longer considered new and unusual. It had become common. The important thing was not whether a vocal performance was technically perfect, but how its imperfections were presented. Autotune could make a voice sound both close and far away, and it could make the voice sound soft or loud.

Artists used this effect in different ways. T-Pain made autotune his trademark, not a way to hide. His singing did not try to sound natural. He embraced artificiality, transforming digital processing into a tool for expression. Songs like “Buy U a Drank” and “I’m Sprung” used the effect to express vulnerability without being overly sentimental. Lil Wayne’s 2008 song “Lollipop” used Auto-Tune a lot and became one of the most famous examples of the effect that decade. The voice sounded protected, almost like it was covered by a shield, as if emotions needed a filter to be expressed safely.

By the end of the decade, the style became more introspective. Kanye West’s album 808s & Heartbreak used Auto-Tune to express sadness, loneliness, and emotional distress. The album’s simple production and digitally altered vocals weren’t meant to be popular on the radio in the traditional sense. Instead, they focused on emotional distance itself. People started using processed voices to express feelings that were too intense or unstable to express directly.

People started criticizing it right away. Many people thought that autotune showed that musicians were not as skilled or honest. But these arguments didn’t address the main issue. The fact that so many people used vocal processing showed that there was a deeper cultural reason for it. In a decade marked by constant visibility, surveillance, and pressure, it was rarely easy to express emotions. Digital voices reflected digital lives. They sounded shaped, managed, and not quite in tune with the body.

Autotune did not remove human emotion. It changed the way people heard it. This technology let artists show vulnerability without fully exposing themselves. This shows something very important about the 2000s. People’s feelings were everywhere, but they were often hidden by screens, systems, and software. The voice, which was once thought to be the clearest connection between the artist and the listener, was now sent through a filter.

Producers as Artists: The New Authors

By the 2000s, it was no longer true that producers were just background technicians. Producers had always influenced sound, but in this decade, their influence became obvious. They were doing more than just improving performances. They were creating entire worlds of sound, often combining the works of different artists and including a variety of musical genres. Often, the producer’s style was just as easy to recognize as the performer’s voice.

The shift was closely related to technology. Digital workstations let producers work faster, experiment more freely, and control every detail of a track. The studio became less about capturing a moment and more about creating one. Producers became central creative forces. They often shaped both the emotional direction and commercial success of an artist’s work.

Timbaland is a great example of this. His music for Missy Elliott, Aaliyah, and Justin Timberlake was unique. It had unusual rhythms, unexpected quiet parts, and a sense of playful tension that was clearly his own. These were not interchangeable backings. Artists had to create works in these environments. Timbaland’s music changed the sound of pop and R&B. He showed that popular music could still feel unusual and have new rhythms.

A new kind of authorship emerged from The Neptunes, the duo made up of Pharrell Williams and Chad Hugo. The duo’s simple beats, dry percussion, and sharp melodies were defining features of the early 2000s. They worked with famous musicians like Britney Spears, N.E.R.D., and Clipse. Their music production style was cool and detached. This style was different from the louder and denser music styles that were popular at the time. Their work showed that being modest can be just as powerful as being excessive.

Max Martin was another example of this. His pop songs were well-written and produced. They had clear structure, clarity, and emotional impact. He worked with famous singers like Britney Spears and later Kelly Clarkson. Together, they created a simple but polished sound that was carefully planned. The songs sounded natural because they were designed to.

Kanye West is an example of someone who most clearly played both roles of producer and artist. His early work, which was based on soul samples and expressive textures, made the producer’s perspective stand out as a personal voice. West changed what it means to be an author in popular music. He did this by focusing on how he produced his music.

In the 2000s, producers were involved in creating hits. They were setting the bar high. Their sounds became shortcuts to meaning. They could be used to signal mood, credibility, and ambition. To understand the music of the decade, you have to recognize the role of the producer. The producer had a big influence on the emotional and cultural aspects of the music.

Pop's Hidden Machinery

Pop music was everywhere in the 2000s, but it was rarely at ease with itself. It was everywhere: on charts, TV, magazines, and in conversations. However, the system was built on control, speed, and constant observation. Pop stars were more than just performers. They were well-known brands, interesting stories, and important economic factors. People expected them to stay easy to access, attractive, and flexible.

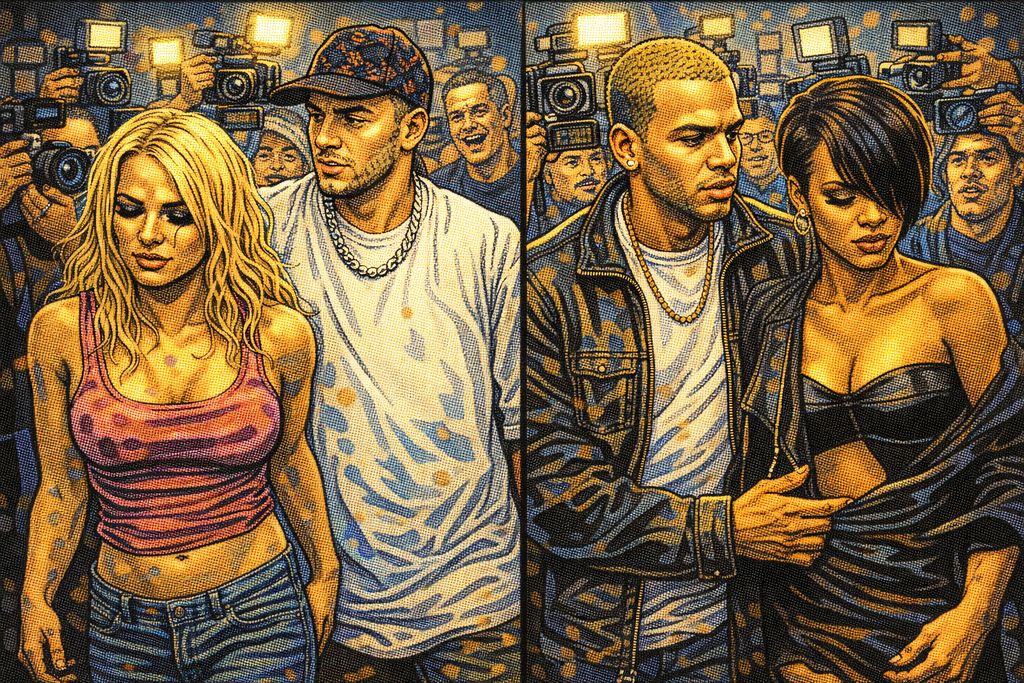

The decade got a well-organized pop machine from the late 1990s. Teen idols, carefully managed images, and tightly controlled releases were already common. The 2000s saw an increase in intensity. Media cycles got shorter. The internet spread rumors about every mistake. Success came quickly, but so did the negative reactions. Many artists, especially young women, became famous without having any control over the process.

At the same time, pop was still a place where people wanted to be creative and make changes. In systems with a lot of rules, artists looked for ways to make their own choices. Some artists defied expectations by experimenting with new styles or approaches in their music. Some people used being professional as a way to show that they were against the system. They learned the rules so they could break them.

The story of pop music in the 2000s is not just about manipulation or decline. It is a story about negotiation. It’s a story about the tension between wanting to be in control and wanting to be free, wanting to share things and wanting to keep things private, and wanting to do things your own way and wanting to follow the rules. The music reflects that tension. It may sound confident, but it’s also often nervous and worried about being watched too closely for too long.

Pop Stars as Brands: The Image Machine

By the beginning of the 2000s, the teen pop system was fully set up. It was improved during the late 1990s. It relied on repetition, visibility, and strict control over the narrative. Young performers were introduced not just as singers, but as characters in carefully crafted stories. Their appeal was based on being innocent, easy to access, and full of hope. The music itself was important, but so was the idea that these stars could gain popularity, be followed, and be a source of emotional investment for their fans.

Britney Spears was at the center of this system. Her first album, ”…Baby One More Time,” created a new standard. The songs were ready to listen to right away and were produced very well. They were made by producers like Max Martin, who are very skilled at their craft. The image was also deliberate. Young people’s sexuality was shown as something fun and not scary. It was closely connected to dance, clothes, and appearances in the media. The result was overwhelming success, but there was also less space. Every gesture was analyzed, repeated, and sold.

Christina Aguilera started the decade in a similar way, but it became more obvious that the system had its limits when she reached her peak. People had similar hopes for Spears. However, Aguilera’s strong singing voice and desire to be more than just a teen pop star defied the limits of the typical teen pop image. Her 2002 album, Stripped, was a deliberate effort to show that she was now an adult and a talented artist. It was presented as a new version, but it also showed that there was not much room to begin with. Growth had to be planned as a rupture.

The system was very fast. New stars were introduced quickly, promoted aggressively, and expected to make money right away. Albums came out one after the other. There were tours, endorsements, and media appearances everywhere. The design did not include rest. When momentum slowed down, support often disappeared. Artists were seen as replaceable, and their personal lives were public information.

The changing media environment made this structure especially fragile in the 2000s. Tabloids had always been around, but online platforms made it more intense. Private moments became content. Mistakes made headlines. The same visibility that helped people build careers also made things less stable.

Pop music was made with talent and purpose. Many of its artists worked with a lot of discipline and commitment under a lot of pressure. The problem wasn’t the artifice itself, but rather the imbalance. Control usually went one way, but responsibility rarely followed. The teen star system made famous people, but it also showed how easily success could lead to being trapped.

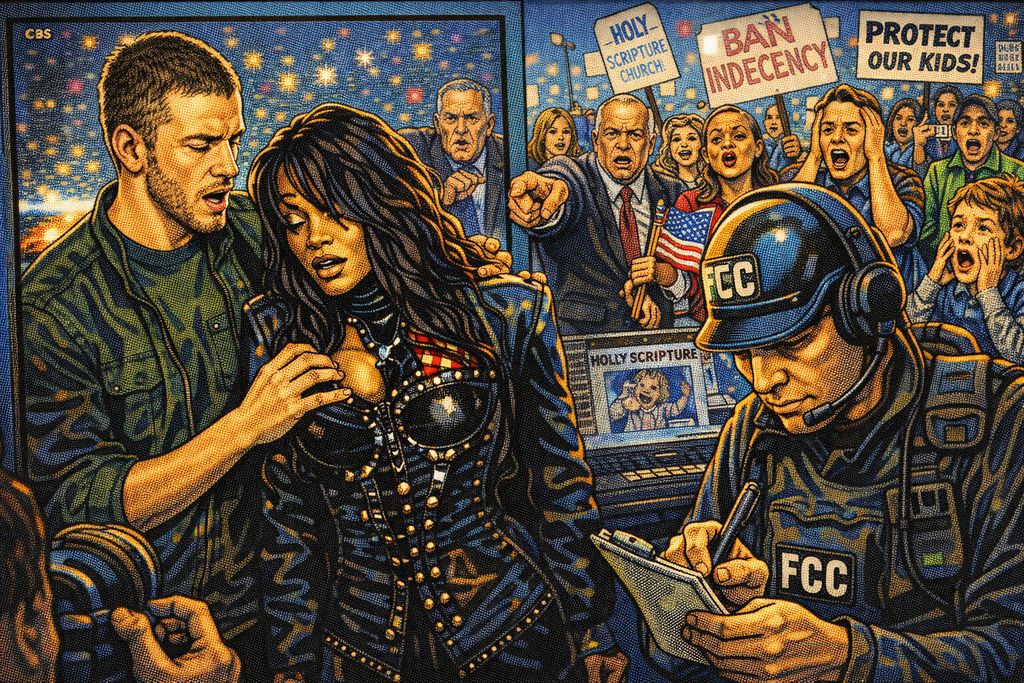

Women Under the Microscope

As pop stardom grew in the 2000s, it was constantly and unfairly criticized. Female artists were watched more than other artists. This made it hard to tell the difference between entertainment and discipline. The way people talked about their bodies, relationships, and feelings was all about who owned what and who was right or wrong. You could see it on TV, in magazines, and online, where people were getting more and more aggressive with each other.

Janet Jackson’s career is a great example of how punishment worked in this situation. The reaction to the 2004 Super Bowl halftime show was immediate and too strong. The incident only lasted for a few seconds, but it had a big impact on how people viewed Jackson for many years. The radio support decreased, the media’s stories became more extreme, and she was blamed for almost everything. This episode showed how quickly someone’s authority could be taken away and how little protection there was once people started saying something was wrong.

Other artists experienced similar dynamics, but in different ways. Jessica Simpson, for example, was often ridiculed. People looked closely at her intelligence and body, as well as her music. Tabloid news made things too simple and turned personal moments into ongoing stories. The tone was rarely neutral. Curiosity easily turned into mockery, and mockery into moral judgment.

What made this surveillance particularly harmful was how it built up over time. In the 2000s, fame did not allow for pauses or time to reevaluate. Every appearance led to the next reaction. Weight changes, fashion choices, and signs of emotional strain were shown as evidence of failure or excess. Growth was allowed only when it matched the approved stories.

Male artists were also criticized, but in a different way. When someone does something wrong, it can make people believe them more. For women, being seen often meant they were in danger. Success made them more visible, and that made them more vulnerable. The expectation was that people would manage themselves and be watched.

That punitive pattern did not appear out of thin air. It was supported by financial rewards. Outrage sold magazines. People clicked on the article because they wanted to know more. The online world is growing, and it rewards people who are quick and intense over those who think carefully. In that environment, showing empathy was not required.

Music made under these conditions often has traces of that pressure. People’s confidence grows stronger, and they become more careful about sharing their feelings. For many artists, survival depended not only on talent but also on the ability to handle constant surveillance without getting overwhelmed.

Reinvent or Fade Away: Survival Strategies

Some pop artists in the 2000s had to change to survive. When it became hard to see, and familiarity turned into boredom, change offered a way to move forward. This was not just a short-term plan; it was a long-term strategy. It required experience, authority, and a willingness to see identity as something that can change instead of something that is set in stone.

Madonna entered the decade already known for her ability to change. What made her stand out in the 2000s was how she deliberately matched her new styles with changes in music and culture. Her music mixed electronic sounds with clear pop music. Later, Confessions on a Dance Floor returned to club culture with precision and confidence, drawing on disco history while sounding modern. These changes were not reactions to a crisis. They were preemptive moves. Madonna did not wait for people to question her relevance. She moved into a new position before the question could be fully asked.

Kylie Minogue had a different approach. She was focused on recovery, not on causing trouble. After years of visibility changing in her strongest markets, Fever made a clear and focused return. Songs like “Can’t Get You Out of My Head” were more about keeping it simple than going overboard. The production was small, the image was in control, and the emotion was calm and confident. This was not a reinvention built on shock, but on clarity. It showed that pop doesn’t need to keep getting bigger to feel fresh.

Both artists understood timing. When you want to reinvent yourself, it’s best to do it in a way that feels natural and not defensive. In the 2000s, many young pop stars were pressured to change their appearance quickly. People saw these changes as a form of rebellion or maturation. These changes were often seen as a spectacle, which made people look at them more closely instead of respecting them. Madonna and Minogue, however, were the ones who were in charge. People saw their changes as choices, not confessions.

Reinvention was a way to connect with new audiences without losing the ones you already had. Both artists combined dance music, electronic production, and global club culture in their work. This allowed them to fit in with scenes that valued movement and repetition over having a fixed identity. This allowed their music to be shared in places where tabloid stories weren’t as common.

In a decade that demanded constant visibility, reinvention was a way to protect yourself. It created distance between the artist and the public image. Instead of talking about their past, these performers talked about their future. By doing this, they showed that being popular for a long time isn’t about staying the same. It’s about being in control of the changes that happen.

R&B: The Emotional Heart of the 2000s

While pop music defined the 2000s, rhythm and blues (R&B) carried much of its emotional weight. It was the genre in which intimacy, vulnerability, desire, and conflict were explored in a very careful and precise way. While other styles often responded to the decade’s instability with big sound or flash, R&B focused more on itself. It was all about feelings, the voice, and the slow process of finding the right balance between being strong and being open.

R&B in the 2000s was not one style. It blended with pop music and hip-hop, drawing from soul music’s roots. This flexibility let the genre take in cultural pressure without losing its sense of order. The genre was a place where artists could talk about their personal lives in public. They often talked about topics that mainstream pop music didn’t touch on.

R&B was important because it gave women a kind of power that was rare in other parts of the industry. They did not see emotional expression as a sign of weakness, but as a skill. The ability to control the tone, phrasing, and narrative was as important as being technically precise. Male artists started to show more vulnerability, but only in a careful way.

During that time, R&B was more like a foundation than a trend. It changed how emotions were expressed in different types of music and had an impact on pop, hip-hop, and electronic music. To understand the emotional landscape of the 2000s, you need to know about R&B. It is essential.

Neo-Soul: Where the Past Lives in the Present

At the start of the 2000s, neo-soul offered something rare: a sense of continuity in a decade full of change. While most of the industry focused on speed and visibility, this movement deliberately looked back. It drew inspiration from earlier soul, jazz, and funk traditions. Neo-soul was not a genre that made people feel nostalgic. It was grounded. It saw history as something alive and usable, instead of thinking of it as something that is kept in a museum.

D’Angelo’s Voodoo, released in 2000, became a popular and influential album of the decade. Its strong beats, warm sounds, and slow pace were different from much of today’s music. The album asked listeners to stop and pay attention. This went against the common thinking of the time. Voodoo didn’t chase after singles or trends. Instead, it presented the album as a complete emotional experience that was deeply rooted in Black musical tradition.

Erykah Badu had a similar way of thinking. She mixed deep thoughts about spirituality with the reality of everyday life. In the early 2000s, her work focused on defining who she was and finding inner clarity. Often, she addressed the tension between what the public expected and what was true for her personally. Badu’s voice sounded authoritative, but not harsh. It got people’s attention without being over the top—a balance that felt pretty extreme in a culture that is always bombarding people with information.

Jill Scott expanded this idea by focusing on real-life experiences. Her songs focused on everyday life, relationships, and the emotional work involved, especially from the point of view of a Black woman. Scott didn’t make vulnerability into a spectacle. She treated it as common ground. Her success showed that intimacy could be successful in the commercial world without being made simpler or more sensational.

Maxwell brought a different kind of continuity. His work focused on sensuality and emotional restraint. It drew from classic soul aesthetics while maintaining a contemporary tone. In a decade full of extremes, this focus on subtlety was important.

These artists were connected not by a unified sound, but by a shared outlook. They saw music as a craft that is shaped by history and responsibility. Neo-soul said that making progress doesn’t mean erasing other things. It offered a different story than the idea that modernity meant moving away from the past.

In the 2000s, neo-soul was a popular music genre. It kept space for patience, depth, and lineage at a time when it was becoming harder to maintain those qualities.

Beyoncé, Alicia Keys, Mary J. Blige: Women Who Carried the Decade

In the 2000s, R&B was one of the only types of popular music where women could express strong emotions over long periods of time. This authority didn’t come from a desire to shock or provoke. It came from the ability to control voice, narrative, and tone. Female R&B singers were expected to be expressive, but they changed that expectation by taking control of their own artistic style. Feeling was not a weakness. It was a sign of expertise.

Beyoncé’s decision to start a solo career was a big change. Dangerously in Love showed that she could sing with power and emotion. The album showed a mix of feelings, including vulnerability, confidence, desire, and independence, without combining these feelings into one image. Beyoncé’s control was subtle. Instead of rejecting mainstream structures, she became an expert at them, using her professionalism to her advantage. In the last ten years, her work has shown that being open with your feelings and keeping a cool head can go together.

Alicia Keys offered a different idea of authority. Her first album, Songs in A Minor, made it clear that her identity was defined by her personal life and her musical talent. At a time when pop culture rewarded immediacy, her piano-driven arrangements and reflective songwriting emphasized introspection. Her success showed that people still liked it when performers were patient and sincere, even when they were performing for a crowd.

Mary J. Blige had already created a unique style of emotional R&B music before the 2000s, but her work during the decade made it even more popular. Blige’s music addressed tough topics like pain, healing, and self-esteem without making it sound too smooth or easy. Albums like No More Drama showed that survival is a process that never ends, rather than an outcome that is finally achieved. People trusted her because she was always honest.

These artists were connected not by the fact that their music sounded the same, but by their ability to express strong emotions in their music. They met expectations by being open, relatable, and strong — often all at the same time. Their performances were very important because they represented women, whose emotions were often ignored or misunderstood in public discussions.

In a time of great change and openness, female R&B singers found a way to talk about complicated issues. They showed that feeling strong emotions doesn’t mean you will completely lose control, and that staying calm doesn’t mean you are not emotional. They used their voices and stories to claim a space that was both personal and public. They did this by shaping how emotion could be expressed in mainstream music.

Usher, Ne-Yo, and the New Masculinity

Female R&B singers of the 2000s used their voices and control over their songs to convey emotion. Male artists had a different challenge. They were expected to show vulnerability without looking weak and intimacy without losing control. The genre was a place where new types of masculinity could be tried out. These types of masculinity were okay with doubt, regret, and emotional dependency. At the same time, they still fit within mainstream expectations.

Usher’s Confessions is an important document that helped define this negotiation. The album made emotional exposure seem like a confession instead of a breakdown. Songs addressed infidelity, guilt, and responsibility in a direct way that felt unusually personal for a mainstream release. Confessions was popular because it was honest and its structure was appealing. People presented their weaknesses in a way that made them look like they were growing. They admitted pain, but they never gave up agency.

Ne-Yo had a unique approach to masculinity. He wrote songs and performed them. He focused on thinking deeply about his feelings and understanding himself. His work often shows the male narrator as someone who is learning, regretting something, or trying to fix a problem. Instead of talking about being in charge or taking over, Ne-Yo’s songs focused on how things can make you feel. This idea of what it means to be a man did not reject strength. Instead, it redefined strength as responsibility.

At the same time, the decade showed how easily emotional language could be taken advantage of. Even though there were serious allegations against him, R. Kelly remained a big commercial success throughout the 2000s. His ongoing success revealed a major issue in the industry. People celebrated emotional expression in their music, but they did not practice accountability. This disconnect made people ask uncomfortable questions, like whose problems were taken seriously and whose weren’t.

The masculinity crisis in 2000s R&B was not theoretical. It was shaped by real pressures. People were paying more attention to the situation. Traditional gender roles felt more unstable. People were encouraged to be emotionally open, but they only did so within specific, carefully controlled limits. People praised artists for their sensitivity, as long as their art did not challenge the power structures that were in place.

R&B did not solve these problems, but it made them obvious. The genre allowed men to talk about feeling sad, wanting something, and being unsure of themselves. It also showed that there were some things that couldn’t be expressed in this way. This was a reflection of a larger cultural struggle. In the 2000s, people were publicly changing what it meant to be a man, one song at a time, without knowing exactly where this was going.

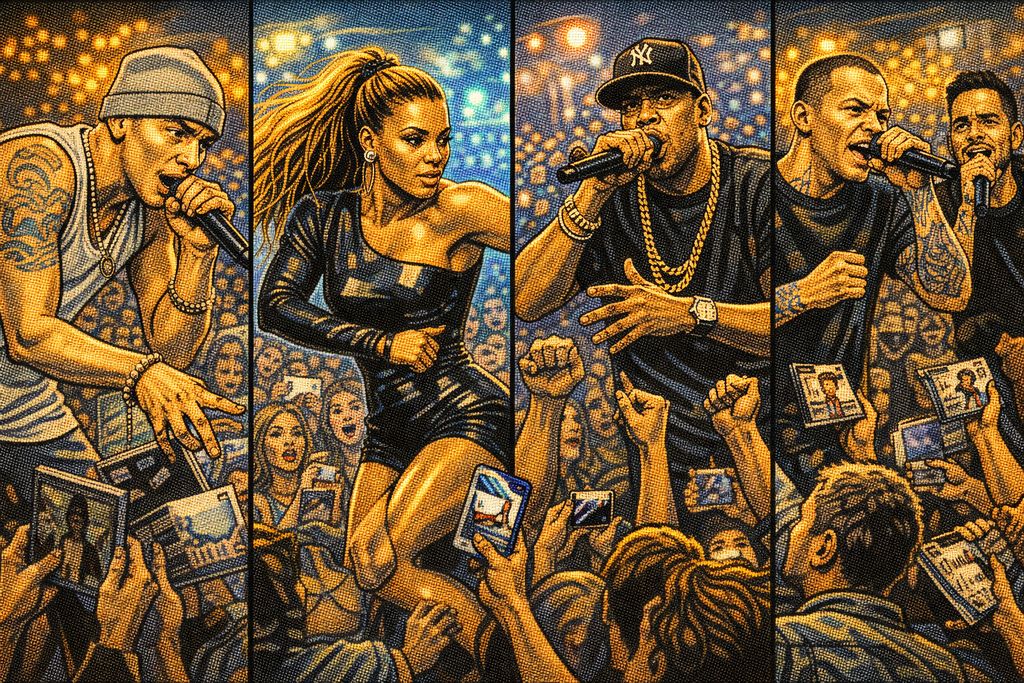

Hip-Hop's Rise to Power

By the beginning of the 2000s, hip-hop was already a well-known music genre. It had already become one of the most popular types of music. The only thing that changed during the decade was the size. Hip-hop went from being a culture that had a lot of influence to being a culture that had a lot of power in institutions. It influenced charts, fashion, language, and business models. That power caused new problems. Success made more possibilities available, but it also showed problems that had been easier to ignore before.

The music of this period reflects both ambition and instability. The commercial reach grew quickly, but there were more and more questions about whether it was real, who owned it, and who was responsible. Artists had more money and were more popular than any generation before them. Hip-hop remained closely connected to regional identity, personal stories, and social criticism. However, as these elements were increasingly influenced by corporate structures, they also became more widely shared and consumed.

The 2000s did not make hip-hop less clear; they made it more complicated. People were celebrating and also criticizing each other at the same time. Excess became both performance and pressure. Weakness appeared along with boldness, and it was often in surprising places. As the genre’s influence grew, its inner contradictions became more obvious.

To understand hip-hop in the 2000s, you have to understand this dual movement. It is a story of growth and tension, of new leadership and old problems. The decade did not solve hip-hop’s problems. Instead, it made them more popular, putting them in the spotlight of world culture.

From Counterculture to Center Stage

At the start of the 2000s, hip-hop went through a big change that it had been getting closer to for years. A voice that once belonged to counterculture had moved to the center of the music industry. This change did not remove hip-hop’s political or social roots, but it did change the way they were expressed. Power means having access, and having access means having to compromise.

Jay-Z is the best example of this change. His rise in the late 1990s was a sign of a new relationship between artistry and business. In the 2000s, albums like The Blueprint and The Black Album were successful because of smart marketing strategies. Jay-Z did not suggest that his wealth was an accident. It was the result of careful planning, strict rules, and strong leadership. His work changed what it meant to be successful in the hip-hop world. His work reframed success in hip-hop as strategy, ownership, and self-possession.

At the same time, Eminem made the genre more popular than ever before. His technical skill, emotional intensity, and willingness to reveal personal weakness challenged traditional ideas of masculinity and control. Albums like The Marshall Mathers LP and The Eminem Show were popular but also made some people feel uncomfortable. Eminem’s success made the industry face issues related to race, authenticity, and popularity. He was both an outsider and a central figure. People embraced and scrutinized him equally.

50 Cent was another important part of hip-hop’s mainstream. His first album, Get Rich or Die Tryin’, showed that being successful and being in control are connected. The album’s story was based on street credibility, but it also had a polished, commercial structure. The idea of violence and vulnerability was presented as part of a larger set of beliefs that could be easily used in branding, movies, and business partnerships.

These artists were connected not by a shared sound, but by a shared position. They were at the heart of the industry, setting expectations instead of responding to them. Hip-hop was no longer just responding to outside pressure. It was setting the terms.

That shift caused tension in the culture. Hip-hop was becoming more profitable, which led to more intense discussions about authenticity. Some people asked if being successful in the mainstream took away from the genre’s social purpose. Supporters said that more resources led to more creative and political opportunities. Both views were important.

However, the move from counterculture to the corporate mainstream did not solve the problems in hip-hop. It showed who they really were. The genre became more popular, influential, and wealthy. However, it also had to deal with the responsibilities and limitations that come with being dominant. The music of the 2000s shows this reality. It sounds sure of itself and eager to achieve, but it also sounds a bit uncertain. It knows that having authority can be good, but it can also be hard.

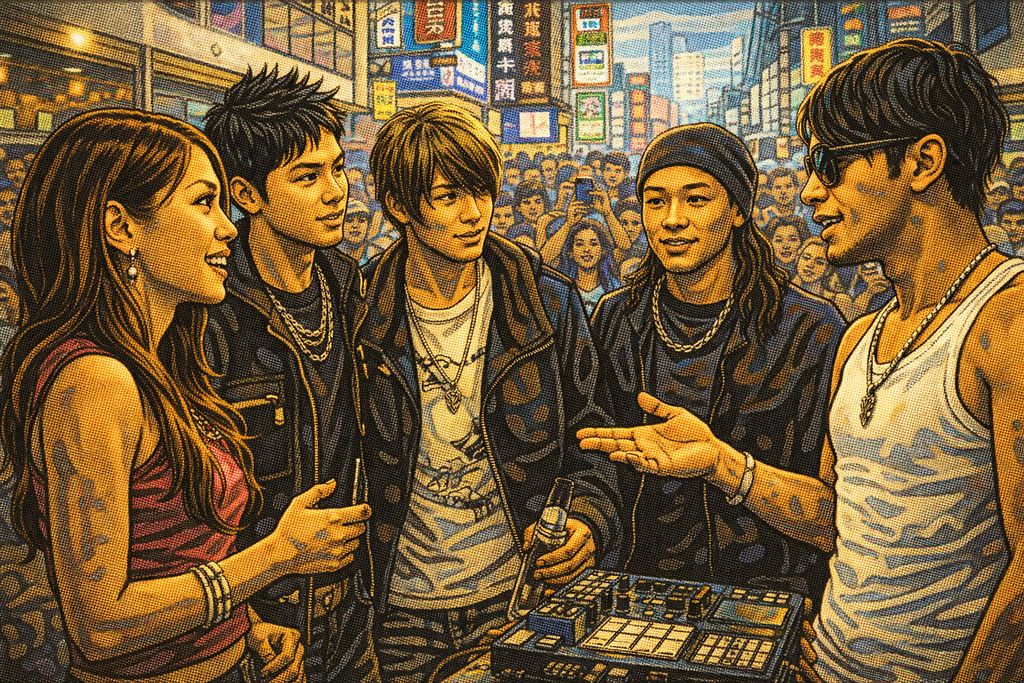

The South Takes Over: Atlanta, Houston, New Orleans

One of the most significant changes in hip-hop music in the 2000s was the relocation of its creative center. For many years, the way people thought about authority was based on the views of people living on the East Coast. They thought that the most innovative and legitimate ideas came from New York and Los Angeles. The 2000s changed that system. Southern hip-hop didn’t try to include other types of music. Instead, it made itself known through its size, its confidence, and its cultural distinctiveness.

OutKast played a big part in this change. The band’s 2000 album, Stankonia, broke the mold of traditional regional music styles. It mixed funk, psychedelia, political commentary, and playful experimentation. OutKast did not suggest that Atlanta should be considered as an alternative to existing centers. They presented it as a world of its own. Their success showed that innovation doesn’t come from just one place.

Atlanta’s growth got faster and faster. T.I. helped create the sound of trap music and the stories behind it. Albums like Trap Muzik highlighted local issues without making them more appealing to a wider audience. The term “trap” was used to talk about a certain kind of environment and constraint. T.I.’s work showed that a regional language can be important to a whole country.

Lil Wayne came from a different part of the South, New Orleans. During the decade, he changed significantly. He went from being a performer in a group to a solo force. He was known for being loud, flexible, and relentlessly productive. Lil Wayne’s popularity straddled both the underground scene and the mainstream. His approach was all about staying active. This is typical of a culture where something must be relevant all the time, not just at one moment in time.

The rise of Southern hip-hop was not just about individual stars. It changed how the industry thought about infrastructure. Independent record labels, local radio networks, and word-of-mouth promotion were more important than in the past. Success didn’t need approval from traditional cultural centers. It could be grown in one area and then sent to other places.

The shift also affected the sound of mainstream hip-hop. The music was played more slowly, the bass was stronger, and the atmosphere was more noticeable. The music allowed for repetition and mood, which fit with club culture and how people listened in different regions. These elements would later become very important for the next ten years.

The growth of Southern hip-hop did more than just add new types of music to the genre. It also gave more power to other people. By the end of the 2000s, regional identity was no longer something that limited people. It was a source of power. The genre’s map had been redrawn, and it would no longer be limited to its previous borders.

Missy Elliott and the Women Who Broke Through

Hip-hop became more popular in the 2000s, but there weren’t many opportunities for women in the genre. Women were visible, but only under certain conditions. Female artists were expected to fit into clearly defined roles. These roles were based on the balance of two things: the artist’s lyrics and her image, desirability, and marketability. Despite these limits, some artists found ways to make their mark on the hip-hop scene, changing how women could sound and be heard.

Missy Elliott is one of the most important figures in this part of music history. During that time, her work could not be put into a normal category. Songs like those on Miss E… Addictive and Under Construction combined technical innovation with humor, physicality, and control. Elliott’s presence made people think differently about gender, body politics, and authorship. She didn’t act like she was better than everyone else. Instead, she came up with new terms, often working closely with Timbaland, whose production made her unusual instincts stand out more.

Eve offered a different way of thinking about authority. Her music was tough but also emotional. It showed strength as something that can change, not as something that is always in control. Eve’s success in both hip-hop and crossover music showed the challenges female artists face. To reach more people, they often used popular frameworks that made things too simple. Eve did a pretty good job with this change, but it was still clear that there were some limits to that balance.

Lauryn Hill’s absence from the center of the decade’s output was significant. After the huge success of The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, her departure from the mainstream left a noticeable gap. Her legacy kept on shaping what people expected in terms of lyrics and emotional honesty. But the industry had a hard time supporting artists who wanted the same level of freedom without making any compromises. Hill’s reduced visibility showed how easily complex female voices could be ignored.

Even as more women gained visibility, structural barriers remained. Radio stations often favored male artists. Marketing budgets were based on assumptions about audience preferences. There were some good opportunities for collaboration, but not all of them were equal. Women were invited to contribute, but they rarely had the chance to decide the overall direction of the genre.

However, it’s important to remember that the impact of female artists on 2000s hip-hop cannot be measured solely by numbers. They had a big impact on the genre’s aesthetics, performance styles, and narrative approaches, making the genre’s emotional range wider. They changed what confidence and authority could sound like and what they could look like.

The decade did not solve the problem of gender imbalance in hip-hop. However, it made the issue more noticeable. During this time, women’s work prepared the way for future progress, but it also showed that there was still a lot of resistance.

Rock's Identity Crisis: What Does Authentic Mean Now?

By the 2000s, rock music had a complicated legacy. It was still seen as a symbol of strength and was linked to feelings of defiance, trust, and emotional authenticity. At the same time, however, its cultural authority was no longer secure. Hip-hop was the most popular music, pop received the most attention, and digital listening divided audiences. Rock wasn’t disappearing, but it was losing its usual importance.

This tension shaped much of the rock music produced during the decade. Artists were starting to realize that what it means to be authentic is a topic that people have different opinions about. The sound could be raw, but it might also be planned. If they did well, people might start to wonder. The traditional myths of Rock no longer automatically worked. They had to be negotiated, defended, or reimagined.

In response, different groups emerged with different strategies. Some bands tried to make their music sound old-fashioned to seem more authentic. Others embraced emotional openness, making vulnerability the main part of their appeal. Some people felt overwhelmed and disconnected. They expressed frustration using words that suggested a sense of impending collapse rather than control.

In the 2000s, rock music was not united by a particular style. Instead, it was united by a sense of anxiety. It asked itself questions about how important it was, if it was true, and if it would last. Rock music was more like a mirror for the decade than a set of rules for it. The genre showed how the whole culture was unsure about what was real and what was not. It made people ask if being true to yourself came from your family or if you had to create it yourself in new situations.

The Strokes, White Stripes, and the Garage Rock Revival

In the early 2000s, garage rock made a comeback. It came back as a reaction to and a way of reassuring people about the times. At a time when popular music felt overly polished, compressed, and influenced by technology, these bands offered a simpler sound. They played short songs with loud guitars and a confident attitude. This made it seem like music could still feel real and unfiltered. The revival was seen more as a return to the basics than as a new innovation. It was a recovery.

The Strokes became the most well-known symbol of this movement. Their first album, Is This It, sounded like they were trying to keep it simple. The guitars were clean but had a rough sound, the vocals were distant, and the production was dry and personal. The album wasn’t trying to be too overwhelming. It invited listeners into a small, controlled space. The timing was exactly right. In a time marked by overindulgence, the record seemed to reject that.

The White Stripes were different. The band’s strict visual style, limited use of instruments, and rich backstory, full of myths, made it hard to tell the difference between sincerity and performance. Albums like White Blood Cells and Elephant were raw and repetitive. They drew on blues traditions but didn’t have a polished sound. The simplicity was planned. It was almost like a ritual. It suggested that there was still value in constraint.

The band Yeah Yeah Yeahs made the revival even better. The band, led by Karen O, mixed loud, fast music with dance-punk energy and wild movements. Their music went against the idea that garage rock had to be emotional and masculine. Karen O’s performances were full of surprises. They were also emotional and exciting. They added new feelings to the show.

Media narratives played a big role in creating this movement. The garage rock revival was often seen as a way to fix or save rock music. This made people expect too much. Bands were quickly brought up and dismissed when they were unable to bring new life to an entire genre of music.

Despite all the excitement, the revival was important. It brought back the idea that rock music doesn’t need to be overly dramatic or make big statements. It valued texture, mood, and restraint. It also showed how far nostalgia can go. Simply stripping things back didn’t automatically bring them back to their former cultural importance. It didn’t solve anything.

The garage rock revival did not save rock music. However, it reminded listeners why rock music was important, even as the situation around it continued to change.

Emo: When Feelings Became the Point

The garage rock revival tried to seem old-fashioned to be more popular, but emo and pop-punk focused on their own style. These scenes made people feel things. They were popular because they spoke to a generation of people who were growing up and becoming adults. This generation felt pressure from the culture around them. In the 2000s, vulnerability became a popular term that many people could relate to. Those who felt ignored by more aloof forms of cool found it particularly resonant.

My Chemical Romance and other bands like it made emotional intensity into a show, but they still made it meaningful. Albums like Three Cheers for Sweet Revenge and The Black Parade used stories to talk about pain, feeling disconnected, and how to survive. Many people misunderstood this dramatization. They thought it was exaggerated, but for many fans, it provided structure. Emotions were not chaotic. It was staged, named, and shared.

Fall Out Boy used irony and wordplay to talk about their feelings. Their lyrics were deep, thoughtful, and sometimes self-critical, showing a generation that was good at being sincere and also good at being indirect. Pop-punk’s polished hooks made it easy to understand difficult emotions without making them seem less intense. We could sing sadness out loud, together, and without feeling embarrassed.

Avril Lavigne made the gender dynamics of the scene more complicated. Her early success went against the expectations for how young women in rock-adjacent spaces were supposed to sound and act. Her work was often described as rebellious simplicity, but it showed that there weren’t many different roles available. People were allowed to be assertive, but only in a controlled way.

Emo and pop-punk music were different from other genres because of their lyrics and the way they connected with their fans. These genres were based on people identifying with them rather than feeling distant from them. Fans didn’t just admire the artists. They recognized themselves in them. Concerts became places where people felt comfortable being vulnerable instead of hiding it.

People started criticizing it right away. People thought the music was overly dramatic, immature, or overly emotional. These critiques often ignored the social conditions that made such expression necessary. In the 2000s, there weren’t many places for young people to talk about their fears, confusion, or sadness without being laughed at. Emo and pop-punk music filled that gap.

These scenes were like cultural performances that gave form to emotional chaos. They turned personal challenges into music that everyone could enjoy. Even as trends faded and fashions changed, their impact remained. The music let listeners feel free to show their feelings, even though people were expected to be in control and perform well in other areas.

Nu Metal: Linkin Park, Korn, and Anger as Art

Nu metal came on the scene at the start of the 2000s, and it was full of anger that felt unprocessed and unrefined. Heavy music used to be about being really talented or rebelling against the system. But nu metal was all about overwhelming listeners with their emotions. Frustration, shame, numbness, and confusion weren’t just background themes; they were the point. In the 2000s, this made the genre very popular, but it was also heavily stigmatized.

Linkin Park’s Hybrid Theory was one of the most successful debut albums of the decade because it clearly expressed a sense of internal turmoil. The songs were a mix of aggression and vulnerability. They combined heavy guitars with electronic textures and lyrics that were personal and revealing. Chester Bennington’s voice was sometimes controlled and sometimes wild, showing emotions that were hard to handle. The album was a big hit, which showed how common these feelings were, even though people didn’t talk about them a lot.

Korn’s approach was more intense and less friendly. Their work focused more on discomfort than on emotional release. Their lyrics talked about things like trauma, insecurity, and feeling alone, but they didn’t give any solutions. Korn’s music was meant to feel heavy and intense, using guitars that were out of tune and a steady, pounding rhythm to create a sense of psychological weight and pressure. Many listeners felt that this lack of relief felt honest instead of nihilistic.

Deftones made the genre more popular by adding atmosphere and sensuality. Their music mixed aggression and intimacy, leaving room for interpretation. Albums like White Pony showed that you could be heavy and sensitive at the same time, without it turning into a big show. However, this subtlety often went unnoticed in broader cultural discussions. These discussions reduced nu metal to a caricature.

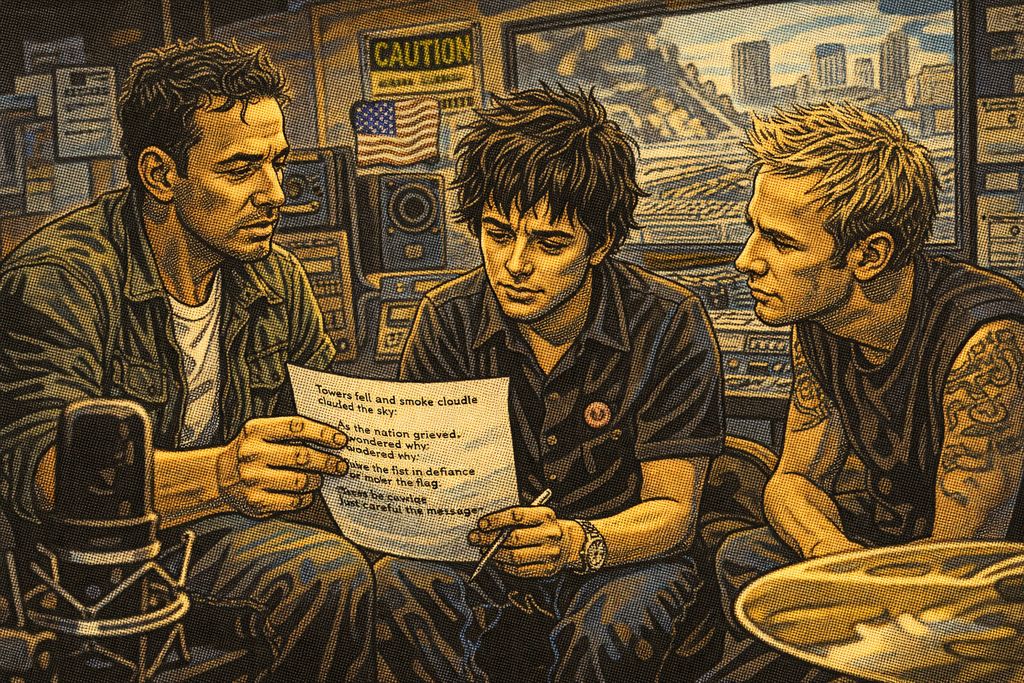

System of a Down brought a political element to the table that made them stand out. Their music addressed serious topics like war, nationalism, and state violence in a strange and urgent way. Their songs were always changing. They would suddenly shift between different tones and tempos. This instability showed that the world felt confusing and dangerous, especially in the years after the September 11 attacks.

Despite its popularity, nu metal was rarely considered a legitimate music genre by critics. People thought it was immature or excessive, and its emotional directness was seen as a lack of discipline. These judgments often ignored the differences between social classes. Nu metal was popular with audiences who felt left out of cultural spaces that valued irony, restraint, or a sense of superiority.

The genre’s popularity decreased in the late 2000s, but that didn’t change how important it was. Nu metal was a way of expressing the intense emotions that people were experiencing at the time. Its legacy is not about making things better, but about explaining them. It was a way to express feelings that were hard to express in other ways, even if it made some people feel uncomfortable.

Electronic Music: The Quiet Conquest

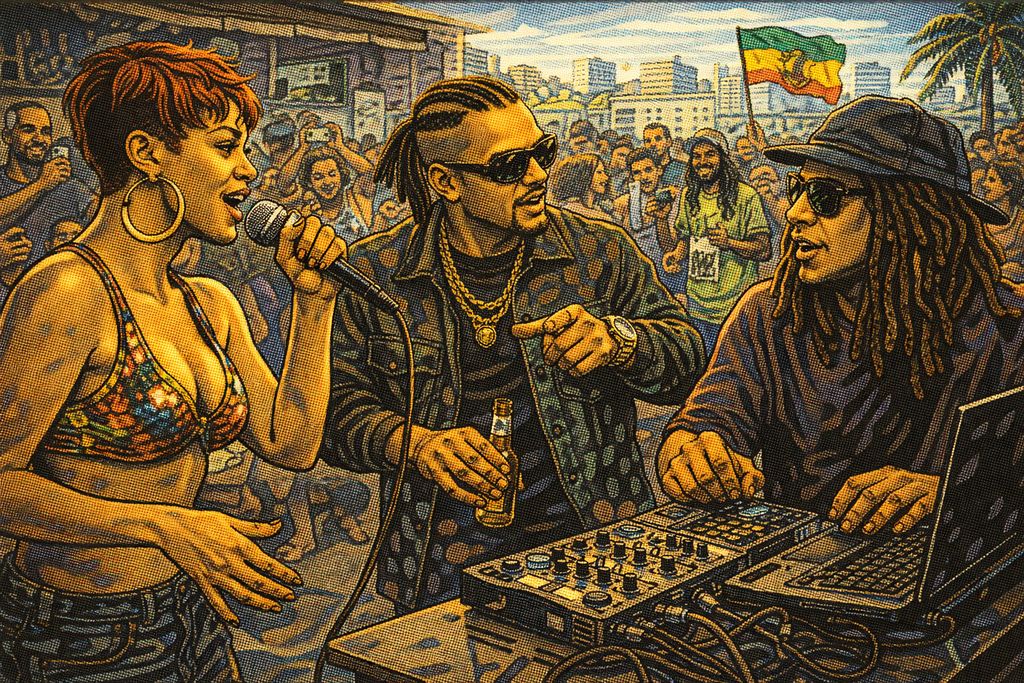

Electronic music was special in the 2000s. It was all over the place, but it wasn’t really there. Electronic music was not the most commercially dominant genre during that decade, but it still had a big influence on how people moved, gathered, and listened. Electronic music is different from other genres that focus on one star performer. Electronic music is all about systems, spaces, and repetition. Its power was often shared, not held by one person.

In the 2000s, electronic music became more popular, but it still kept some of its underground character. Club culture spread to other cities and countries. It was supported by festivals, independent record labels, and global networks of DJs and producers. The tracks were shared without fixed identities, remixed, and recontextualized night after night. Who wrote it wasn’t as important as the mood of the piece. What mattered was whether the room moved together.

In contrast, this culture offered something that was becoming increasingly rare in the decade’s media. It created spaces where people could be themselves, where the human body was more important than images, and where time was measured by the beat of music instead of the news. Electronic music didn’t promise to help people escape from social pressure. Instead, it offered a temporary escape. On the dance floor, each person’s unique story melted away as everyone moved together.

Technology made it easier to produce and distribute music. This led to new ways of creating and spreading electronic music. Producers became easy to recognize but not too obvious. The genre wasn’t the most popular in the 2000s, but it lasted. It provided continuity, circulation, and collective experience in a period marked by fragmentation elsewhere.

EDM Goes Mainstream: Daft Punk and the Dance Revolution

At the start of the 2000s, electronic music reached a point that had long seemed impossible to achieve. It didn’t give up on clubs or underground networks, but it started showing up in mainstream charts, advertisements, and festival lineups. This change happened gradually. It was the result of years of work in dance culture during the 1990s. Now, more people were open to repetition, texture, and non-traditional song structures.

Daft Punk played a central role in this change. Their 2001 album, Discovery, changed electronic music by making it more pop-oriented without losing its identity. The album was built around looping grooves, filtered vocals, and clear melodic lines. It embraced pleasure openly. Songs like “One More Time” and “Digital Love” feel warm and nostalgic. They present dance music as something emotional rather than just something you dance to. Daft Punk’s success showed that electronic music could be popular for a long time and not just as a short-term trend.

The Chemical Brothers, however, took a more abrasive approach when they went mainstream. Their work had a strong physical energy that came from big beat and rave culture. Albums like Come with Us were both aggressive and easy to listen to. This showed that electronic music could be confrontational but still be popular with many people. Their live performances were all about making things bigger and getting the audience involved. They took the energy of a club show and turned it into a festival experience.

Fatboy Slim was another way to become more visible. He used three things to make electronic music easier to understand within the pop music genre: sampling, humor, and high-energy rhythms. The songs “Praise You” and “Weapon of Choice” used cultural references to attract listeners who felt left out of club culture.

These artists were united not by the type of music they played, but by the time when they were active. The 2000s mainstream was already divided and less focused on guitar-driven styles or traditional song stories. Electronic music fit naturally into this landscape. It focuses on the way music feels and the beat, which fits with how people now listen to music because of technology and the playlists they make.

But this didn’t mean electronic music’s underground scene disappeared. Clubs, DJs, and independent labels were still very important. Mainstream success was more like an extension than a replacement. Electronic music became popular without losing its internal logic. It offered a way to expand without having to completely assimilate to other genres.

By the mid-2000s, electronic sounds were no longer considered new. They were present across pop, hip-hop, and experimental music. The genre had not fully taken over; it had quietly become part of the foundation.

Club Culture Survives: Berlin, London, Ibiza

Electronic music became popular thanks to famous artists and successful songs. But its true strength in the 2000s was the strong network of clubs and venues that developed in Europe. These scenes didn’t need to be global hits. They needed to keep going. Even though electronic music wasn’t very popular, clubs, record labels, promoters, and local audiences helped it survive.

In Germany, for example, the techno culture of the 1990s continued and was taken to a new level, with a renewed focus and discipline. Cities like Berlin became important not because they produced popular music, but because they offered space. Clubs like Tresor and later Berghain were places where people went for a long time, not just because of a popular trend. DJs were valued for being able to keep going and for being consistent, not for being a show. The music was all about repetition, patience, and getting into the groove. This approach was different from other areas of popular culture, which were always changing.