The 2010s: When Music Stopped Being Shared

The 2010s didn’t start with a clear musical statement. There was no one sound that announced the decade, and there was no shared rhythm that everyone seemed to move to at once. Instead, music entered the decade in a state of uncertainty. You could still see the old structures, but they were already starting to fall apart. Albums were important, but playlists were becoming more important. Charts were still around, but fewer listeners felt they represented them.

For many artists and listeners, the decade felt unstable. New platforms promised to give people access and freedom. But they also secretly changed who could be heard and who would be ignored. Careers began to change. Success, failure, and longevity all played a role. Some musicians adapted quickly. Others resisted. Many struggled somewhere in between.

The 2010s were a difficult decade to summarize, but they were also an important one. The music stopped moving in one direction and started spreading out. There are more scenes, and audiences are divided. People’s personal tastes are more private. This opening sets us ready for a decade that was defined less by a particular sound and more by the change itself. This change was felt in studios, on stages, and in the everyday act of listening.

When Albums Died and Playlists Took Over

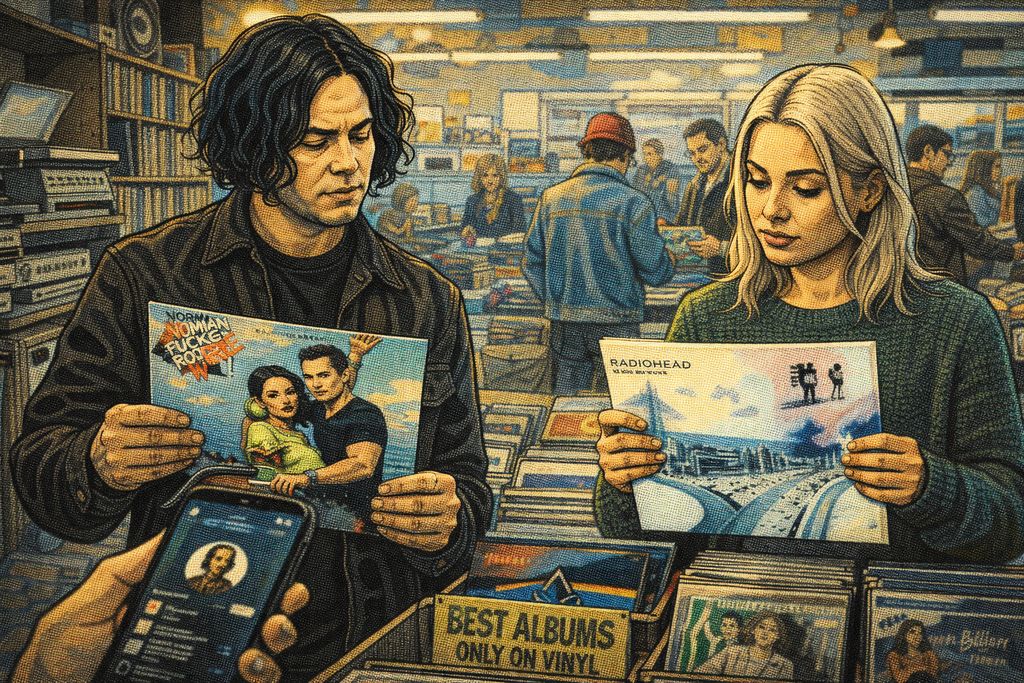

At the start of the 2010s, the album was still very important. Releasing a full-length record was a way for artists to express who they were and how they wanted to be heard. But the ground beneath that tradition was already showing signs of weakness. Digital downloads had made the old release cycle weaker, and streaming was quietly getting ready to change how people listened to music. Most people didn’t have music of their own. It was becoming something they used.

Artists who had built their careers around albums felt this tension early on. Before the decade began, Radiohead had already tried new ways to sell music. They experimented with releasing music that people could pay for however much they wanted to. Their approach suggested a future where the way a song is presented is as important as the music itself. Others moved differently. Kanye West treated albums like cultural events. He used projects like My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy and later The Life of Pablo to mix up the idea of a finished work and an ongoing process. Updates, revisions, and online conversations were all part of the album’s journey.

Pop music felt the shift just as strongly. Lady Gaga started the decade with the same public image she had at the end of the 2000s. Back then, she was famous for her singles and her songs that were played a lot on the radio. As streaming grew in popularity, her work started to appear alongside fan clips, remixes, and social media fragments that were not controlled by traditional promotional channels. Albums were still being released, but their meaning was increasingly influenced by how individual songs were shared online.

Some artists used their albums to make a statement. They did this by not following the new rules. Arcade Fire focused on creating albums that feel like complete experiences. They wanted their albums to feel like immersive worlds, not just a collection of songs. Their success showed that albums were still popular, but their role had changed. People didn’t use them as the main way to listen anymore. They were a choice.

People noticed this change in their daily lives. Playlists replaced CD shelves. Songs became popular again months or years after they were first released. They were popular without being considered part of their original context. Discovery became less about waiting for something to happen and more about enjoying the experience. The album era did not end immediately, but its popularity started to decrease. The new format wasn’t just one thing. It was a whole new way of thinking about music. It made music move faster, stay around longer, and be heard in more places at once.

The Last Shared Moments: How the Mainstream Broke Apart

For most of the history of popular music, it felt like there was a clear mainstream. Even listeners who disagreed on what they liked often had a basic understanding of what was important. Radio stations played the same songs at the same times, charts showed the same songs at the same times, and a few media outlets reported on the same songs at the same times. This made it so that people had the same ideas about which songs were popular. By the early 2010s, that shared center was already becoming less strong. Streaming did not cause the change on its own, but it did speed up a change that had been happening for years.

Even though artists at the top still reached a lot of people, they weren’t the only ones in the industry. Adele was one of the last musicians who could make people stop time with a new song. She pulled listeners back into a shared experience. Her album 21 (released January 24, 2011) sold 352,000 copies in the US and 208,000 copies in the UK in its first week. It debuted at number one on both countries’ album charts. By 2012, 21 had sold 18 million copies worldwide. This made it the best-selling album of both 2011 and 2012. It became the best-selling album of the 21st century, with over 31 million copies sold around the world. It was certified Diamond by the RIAA (10+ million copies in the US). The album was number one on the Billboard 200 for 24 weeks. This was the longest run at number one by a female solo artist in history. It was also number one on the UK Albums Chart for 23 weeks. This was also a record for a female solo artist. The three singles—“Rolling in the Deep,” “Someone Like You,” and “Set Fire to the Rain”—were all number one in the US and UK. Adele’s success felt like an exception rather than the norm.

Other stars did well in the new reality instead of fighting against it. Drake didn’t release a new album every few years, like some musicians do. His music was always being shared in public spaces, like on features, singles, and surprise drops. Songs were played over and over again on playlists and social feeds. Sometimes, they were even played more than the albums they were on. Popularity became less about controlling people and more about always being present.

Pop artists like Taylor Swift and Rihanna were at a crossroads. Both were clearly mainstream figures, but their audiences were increasingly engaging with their work in personal, fragmented ways. Fans followed the stories, styles, and online personalities of the musicians along with the music itself. A hit song didn’t mean that everyone heard it in the same place or for the same reason.

As the decade went on, charts started to look more abstract. They still measured success, but they no longer explained how culture affected their own work. A song can be popular on streaming platforms without being mentioned or shared on social media. At the same time, groups of people started to form around artists who rarely appeared in places that are usually used for traditional media. Music became more personal, but also more separate.

The mainstream did not disappear in the 2010s. It became less thick. What replaced it was a group of parallel worlds that were all different. Each world had its own stars, languages, and rituals. Listeners could now create their own music, but they lost some of the shared experiences that were important in the past. This tension is at the center of the 2010s. It helps explain why the decade often feels both familiar and elusive.

2010–2012: Dancing Through the Transition

The early years of the 2010s were a strange mix of confidence and hesitation. Many of the sounds that were popular on the radio and in music charts felt like they came from the late 2000s. They didn’t seem to be clear signs of something new. Dance-pop was a loud and bright style of music that was made to be played in big rooms. Electronic drops crossed into pop music with little resistance. For listeners, the future seemed full of potential, but not fully planned out.

Artists like Katy Perry did very well during this time. Songs like “Teenage Dream” and “Firework” followed a familiar logic of big hooks and maximal emotion, shaped for radio and stadiums. Their success showed that traditional pop formulas still worked, even as the systems around them were beginning to change. The music felt polished and like it could be loved everywhere, but it was already being used in new ways that didn’t fit with those ideas.

Party-oriented acts like LMFAO captured the playful excess of the period. The song “Party Rock Anthem” became popular very quickly. It spread through clubs, YouTube clips, and early social media shares. The song’s popularity didn’t depend on its story or how long it was around. It was more important that people recognized it right away. It showed a short time when things spreading quickly felt natural instead of planned.

Electronic music was also changing how established pop groups sounded. The Black Eyed Peas combined elements of electronic dance music (EDM) with hip-hop, creating a sound that was perfect for festivals and other large events. Their success at the end showed how the lines between different types of music were becoming more blurred. However, the results often felt like a mix of different styles rather than a clear definition of any one particular genre.

At the same time, smaller changes were happening below the surface. People started streaming music more often, which made them want to try different types of music more easily. Singles moved more quickly than albums. Discovery started to feel like it was just for me, not for the group. While the radio was still important, it wasn’t the only thing that mattered anymore.

These years now feel like they are stuck in a holding pattern. The industry was testing ideas, audiences were changing their habits, and artists were watching closely. Nothing had fully broken, but nothing felt stable either. The early 2010s were a time of uncertainty. They revealed a decade of preparation, experimentation in public, and a gradual abandonment of long-standing assumptions that had shaped popular music for generations.

Streaming Changes Everything

When streaming became a regular thing, it offered more than just another way to listen. It changed the balance of power in the music world. What started as a way to deal with piracy and downloads eventually became the main way that music reached listeners. By the mid-2010s, Spotify and Apple Music weren’t just extra features anymore. They were the infrastructure.

For listeners, streaming felt generous. Almost everything seemed available at once, ready to be explored without any cost or commitment. For artists, the situation was more complicated. The range of information increased, but the ability to understand it decreased. Songs from different times, types, and purposes were played together. A release no longer arrived at a specific time. It blended into a steady flow.

Labels adapted quickly, learning to work with data, playlists, and platform relationships. Musicians had to make changes quickly, often without clear instructions. Some people liked the new rules, while others did not. Many people felt torn between the opportunity and the exhaustion.

Streaming appears here as a system, not just a listening format. The focus is on how platforms changed discovery, artist income, and creative decisions, and why these changes still shape how music is made, shared, and valued.

Playlists as Power: The New Gatekeepers

Streaming platforms did not simply replace older formats. They took on a role that was previously held by radio programmers, retail buyers, and music editors. Access to listeners is now managed through playlists, recommendation systems, and internal editorial decisions. These decisions are rarely visible to the public. For many artists, success is less about who discovers their music and more about where it’s shared.

Playlists became the most important thing in the music world of the last ten years. If a song is added to a popular list, it can quickly become famous all over the world. Without that placement, many artists never get heard, even if they are highly skilled or ambitious. These lists were different from radio lists because they changed often and followed different rules. Some were edited by humans, while others were shaped by data patterns based on listener behavior. The result felt both democratic (in that it was open to everyone) and opaque (in that it was unclear how it was decided). In theory, anyone could break through. In reality, very few people did.

Labels adapted faster than most artists. Working with the platform teams became a key part of the release strategies. Sometimes, songs were written or edited with playlists in mind. The mood and tempo of a song were given more importance than its gradual development. Intros got shorter. Hooks arrived sooner. Music had to get the listener’s attention quickly because skipping the song was always just one click away. For artists who are just starting out, this pressure affects the creative decisions they make even before they have an audience.

Listeners experienced this change in different ways. Discovery felt smooth and personalized. New tracks appeared easily and matched the listener’s mood, not the listener’s musical taste. However, that comfort had its limits. Algorithms usually made listeners come back to sounds they already liked. Exploration happened within narrow corridors. There was still a lot of music, but it was often influenced by people’s personal preferences, which were hard to see.

Artists who understood the system learned to work within it. Frequent releases helped them stay visible. Collaborations helped them reach listeners who already liked similar styles. Others struggled because they lacked access to strategy and support. Songs traveled far and wide, but their stories did not always travel with them. A track could become popular without anyone knowing who made it, where it came from, or how it connected to the rest of an artist’s work.

The rise of streaming platforms led to new gatekeepers, who rarely identified as such. They influenced people’s tastes without telling them what to do. They did this by strategically placing items and suggesting ideas. This power was not total, but it was ongoing. By the end of the 2010s, it was as important to a musician’s career to use online platforms as it had been to write songs, go on tour, or promote one’s music.

Living by the Numbers: When Metrics Became the Boss

Streaming became a regular part of people’s lives, and numbers started to play a key role in how music was chosen. Artists started using new ways to talk about their work, like “play counts,” “monthly listeners,” “saves,” and “skips.” These figures were easy to find and impossible to ignore. They offered feedback that was specific, but often didn’t provide enough context. Now, the value of a song can be measured by how long listeners stay listening before moving on to another song.

For artists with a lot of fans, data became important and people wanted it. Drake became well-known in this environment. He consistently released new music, which kept his music available to listeners. Success seemed to be ongoing, not just for a certain season. Albums still came out, but they were part of a bigger group of releases, features, and singles. This helped keep people’s attention.

Pop artists felt the pressure just as much. Ariana Grande found that her fans’ engagement, her chart placement, and their reactions online were all connected. People measured songs right away, sometimes just a few hours after they came out. Reactions were both positive and negative, and they happened quickly and in public. For many musicians, this changed how they felt about taking creative risks. Experimentation became more difficult when results were tracked in real time.

The data-driven environment also helped new stars rise. Post Malone’s success came from a system that rewarded artists who were popular with different types of music and who encouraged listeners to listen to their music more than once. His songs were played on many playlists, and they mixed pop, hip-hop, and rock music. Metrics showed that flexibility, encouraging music that fits many situations rather than just one type of scene.

But the numbers didn’t tell the whole story. A song can do well without becoming popular over time. Another could spread slowly, finding listeners over months instead of days. These patterns were harder to explain in a culture that values immediate results. Many artists started releasing music more often. This wasn’t always because they wanted to, but because it was important for people to see their work.

For listeners, these changes were mostly invisible, but they were still felt. Music arrived quickly, stayed for a short moment, and then disappeared into a massive catalog. Artists felt constant pressure to perform. In the 2010s, musicians learned to read dashboards as carefully as they read lyrics and melodies. They had to balance creative intuition with measurement. The transition was uneven, and it reshaped how success was defined before the decade even ended.

The Streaming Economy: Who Wins, Who Loses

The promise of streaming was fulfilled. Music can travel anywhere. It can cross borders easily. It can be available without limits. A small group of artists made that promise come true. For many others, it remained just out of reach. The streaming economy made it easier for people to access content, but it also made inequality worse.

Artists who were already popular had an advantage when they entered the new system. Big record companies could secure playlist placements, marketing support, and steady public visibility. The streaming reward model amplified this effect: once a song gained momentum, platform systems pushed it further, creating a feedback loop of repeated exposure. The rich often got richer because the system favored consistency and volume, not because of a conspiracy.

Some artists used streaming to get around traditional structures. Chance the Rapper is an example of this possibility. He showed that artists do not need a record label to be successful by releasing music independently and connecting directly with fans. His success showed that there was a new way to do things, even if it was hard to do the same thing. Many artists tried to break through, but most of them didn’t succeed.

Independent platforms offered a different way of thinking. Bandcamp helps artists by letting them sell their music and art directly to fans. The platform also makes it easier for artists to understand how much they will be paid. It was better for listeners who wanted to actively support musicians instead of passively listening to music on streaming platforms. However, it was not as popular as the major streaming services. Choosing independence often meant having fewer people watch.

The way payments were set up made things even more unfair. Payments for each stream of music favored listeners who listened to a lot of music. This was good for pop, hip-hop, and mood-based music. Some types of entertainment that have smaller but loyal fans had a hard time making money. Many artists found that they could earn a modest income from millions of streams, especially after paying their expenses.

Geography and class also had some impact, but not as much as the other factors. Musicians who are financially stable can release music often, spend money on promotion, and wait for their careers to grow. Those without that financial support had more difficult decisions to make. People often didn’t have enough time to create because they were too busy working to survive. Streaming did not eliminate these pressures. It made them more visible.

By the end of the decade, most people did not think streaming was fair. Most people thought it was something that could not be prevented. It offered exposure, but rarely security. Some artists learned to see it as just one of many tools. They built their careers by touring, selling merchandise, or getting fans to support them directly. Others got tired of trying to make a profit when the numbers didn’t add up. Streaming changed how music was heard, but it also made people ask a hard question: being seen online does not automatically mean that musicians will keep making music.

Pop Music After the Monoculture

Pop music in the 2010s didn’t disappear. It loosened its grip. The decade got a form that used to be strong and had a lot of agreement, but then that started to change. Even though big releases continued to be released, they were received in a landscape that was already shaped by personal feeds and private listening habits. It was becoming harder to say what counted as “popular.” This was true even as some artists reached more people than ever before.

This change affected how pop stars presented themselves and how their music was shared. Songs were no longer limited to one channel or one story. One track can be used in many ways: as a regular part of a playlist, as a popular video, as a live performance, and as a remix made by a fan. Images and sounds became more connected, influenced by social media platforms that valued both active engagement and skillful creation.

Pop also opened outward. Languages were mixed more freely, regional scenes crossed borders, and women had more control over writing, production, and narrative. The genre was still able to speak to millions of people, but it did so in many different ways, not just one way.

Pop in this period adapted to a more divided world: stars rebuilt influence, audiences followed in fragmented ways, and the genre stayed central even after the idea of one mainstream faded.

Reinventing the Pop Star: Change or Fade Away

By the 2010s, being a pop star meant more than releasing successful songs. People could see it all the time, and an artist’s identity could no longer be hidden only during specific times, like when they were recording an album. Artists were expected to speak, react, and evolve in public. It was becoming more common for people to completely change careers. It became a regular thing.

Taylor Swift is an artist who is known for her ability to make deliberate changes in her work. At the start of the decade, her music was still influenced by country-pop and personal, narrative songwriting. As her audience grew, she carefully changed her sound and image. She moved into full pop music while also managing public ideas about authorship, ownership, and fan relationships. Her changes were not sudden, but slow, noticeable shifts that recognized changing expectations without giving up control.

Others embraced flexibility as a core part of their identity. Rihanna didn’t see pop as a fixed style; she saw it as a space for movement. Her music moved easily between different styles, like dance, R&B, and global influences. But when she was in public, she acted with confidence and didn’t need to explain herself all the time. She showed that being consistent doesn’t require repeating yourself. It required trust in one’s voice, even as styles changed.

For famous musicians like Justin Bieber, the idea of “reinvention” meant something different. When artists live in public, it is hard to make corrections in private. Musical shifts were closely related to personal stories, maturity, and healing. Fans of pop music followed these changes not only through songs, but also through interviews, social media posts, and moments of silence. It became more difficult to distinguish between personal growth and public performance.

In many types of music, having control over the image became as important as having control over the sound. Social platforms let artists speak directly with their fans, but they also had to be always available. Fans wanted to feel like they were getting the real deal, but they were only getting a limited version of it. A pop star’s success depended on navigating this tension without appearing distant or exposed.

What changed most in the 2010s was not ambition, but durability. Pop careers were no longer defined by just one high point. They depended on being able to adapt, understanding emotions, and being okay with being in public without explaining every choice. The idea of “reinvention” stopped being a big, dramatic change. Instead, it became a simple skill that performers learned as they went along, watching the audience and responding to what they saw.

Beyoncé, Lorde, Billie Eilish: Women Redefining Pop Power

Women in pop music entered the 2010s with a long history of being judged for their appearance, being questioned about their authorship, and wanting more control over their work. The pressure didn’t change over the decade. What changed was the response to the pressure. More artists started to speak up about their authority. They weren’t trying to fit in with what people expected, but instead, they were setting their own rules and standing up for them in public.

Beyoncé is at the heart of this change. In the 2010s, she used pop music to show that precision and intention are important. Albums were more than just collections of songs. They became short, focused statements that were released at the right time, with the right images and story. By presenting her own music on her own schedule and working with carefully chosen collaborators, she showed that scale and authorship can exist together. Power came from being prepared and clear, not from being constantly visible.

Lorde brought a new kind of authority to the music scene. She arrived early in the decade. She was not a traditional pop performer, but she was still a pop artist. Her writing was careful, thoughtful, and a bit distant. That position resonated with listeners who felt stressed by excess and performance. The authority here came from refusal. She showed that sometimes it is possible to step back while still moving forward.

Later in the decade, Billie Eilish took that idea and made it popular again. Her music and visual style focused on intimacy and simplicity instead of grand displays. The singer’s oversized clothing, quiet voice, and simple music style made people think differently about what it means to be feminine and have a strong presence in pop music. She didn’t see this as a rebellious act. It felt more comfortable when she respected her own boundaries, which the audience understood as honesty.

Others gained authority by working together and by being skilled at their jobs. Sia was more focused on writing songs and producing music than on being in the spotlight. By focusing on her work instead of her personal life, she was able to create a career that lasted and allowed her to be creative.

Across these approaches, a shared pattern emerged. The timing, the story, and the creative roles were as important as the charts. Women in pop refused to conform to the idea that authority had to be loud or aggressive. It could be calm, intentional, and steady. The decade didn’t get rid of unfair structures, but it showed new ways to deal with them. Pop remained demanding, but more women began to shape the terms of their lives instead of just surviving them.

Global Pop: When Borders Stopped Mattering

By the middle of the 2010s, pop music was moving in different directions. For many years, if an artist wanted international success, they had to first enter the markets of the US or the UK and then expand from there. Streaming and social media have made that hierarchy weaker. Songs began to spread on their own. They were shared through playlists, fan communities, and online videos. This is different from the traditional way of promoting music. Language stopped being a barrier in the way it once had been.

Artists working outside the English-speaking pop core became more popular. Shakira had been successful in many different markets, but the 2010s were a special time for her work. Collaborations and bilingual releases are now common. They matched how audiences were already listening. Her music naturally crossed over between Latin pop, global dance, and mainstream charts, without needing translation to be accepted.

Later on, artists like Bad Bunny became popular worldwide while keeping their language and cultural identity. His rise did not come from fitting Anglo-pop expectations. It came from listeners adapting to his world. Streaming made it possible for Spanish-language songs to appear next to English songs in the same listening spaces. This helped make it seem like they can exist together rather than competing.

European pop music also changed its position. Rosalía mixed traditional flamenco music with modern pop and experimental styles. Her work caused people to have different opinions. It made people think about who owns things, what traditions are important, and if new ideas are better than old ones. That conversation happened across different countries, with people taking part directly instead of waiting for approval from gatekeepers.

In the 2010s, the world’s population grew, but this did not eliminate power imbalances. English-language music had certain benefits, but its popularity around the world was still uneven. However, there was a clear change in how people thought about it during that time. Pop was no longer required to have the same voice or appearance to be included in the same conversation. Success came from having different voices, not from everyone being the same.

This change made it so that people could listen to the radio more easily. A playlist can go from American pop to Latin trap to European art-pop in just a few minutes. For artists, it was an opportunity, but there was no guarantee it would work out. It was possible to imagine a global reach, but it was not possible to predict it. What mattered most was resonance, not translation. The 2010s didn’t bring about just one worldwide pop style. They created a shared space where many different styles could meet without having to ask for permission.

Seeing Music: When Images Became the Song

In the 2010s, it was rare to hear music on its own. It arrived with images, feelings, and visual hints that influenced how it was understood even before the song played. Social media made listening a visual experience. Now, artwork, short clips, and carefully chosen moments carry as much meaning as melodies or lyrics. For many artists, presence was something that was built bit by bit.

Platforms like Instagram, Tumblr, and YouTube made this change happen. They appreciated the lively atmosphere and the sense of urgency. One image can define an era of an artist’s work. A short video can help people understand what to expect from a whole release. The visual identity became a part of the music, not just an extra element.

This change made it hard to tell the difference between expression and presentation. Artists learned to express emotion through color, posture, and pacing. They often didn’t explain how they did it. The audience paid attention, understood what they were seeing, and copied the actions of the actors. What emerged was a culture where people felt more authentic when they curated their lives rather than when they were completely honest.

Images shaped musical style throughout the 2010s. Artists built entire worlds around releases, and seeing music became part of everyday listening.

Instagram, Tumblr, and the Visual Language of the 2010s

Many listeners already knew how they wanted the music to feel even before they pressed play. Instagram and Tumblr are examples of platforms that have taught their users to quickly and easily understand images. The colors, clothes, fonts, and posture all had meaning. Music was a part of the overall mood, not just a standalone object.

Lana Del Rey is one of the artists who has had the most influence on this style of music. In the early 2010s, her style was all about nostalgia, past glamour, and a quiet, cinematic quality. People shared her images almost as much as they shared her songs. This helped create a world that felt complete, even when listeners couldn’t name specific songs. The visuals didn’t match the music. They got the listener ready for it. That preparation was important. It created intimacy before sound was around.

A version of this visual storytelling that was darker and more urban appeared in The Weeknd’s work. At first, he used shadows, distance, and mystery in his art. People’s faces were hidden. The rooms felt empty. Emotions were suggested instead of expressed directly. Tumblr users helped spread that style. They reposted parts of it over and over until they became symbols. The music became more meaningful when it was played repeatedly and people were encouraged to use their imagination, rather than having the music explained to them.

For artists like Grimes, visual culture became a place to try new things rather than a place that makes sense. Her online presence combined fantasy, technology, and fragility without clear limits. The images weren’t always perfect, but they were intentional. They suggested working on the process instead of focusing on the final product. That approach matched a time when unfinished ideas often felt more honest than ideas that were perfect.

These platforms also changed how fans participated. Listeners weren’t just looking at images. They remade them. Pictures of screens, changes made to images, and short, animated videos (called GIFs) are shared with the public along with official content. These often reach more people than images intended to promote something. Things became meaningful over time. A song can take on different visual interpretations, even if the artist didn’t create them.

The new style of music was all about feeling, not clarity. It relied on suggestions, repetition, and the overall mood. Albums no longer needed a single iconic cover to define them. A series of images could be used instead. In the 2010s, how things looked became more flexible. It changed as artists and audiences talked about it. People not only listened to music, they also danced to it. It was shown on a screen, paused, saved, and remembered through images that people could see long after the sound had faded.

Music Videos After MTV: YouTube Takes Over

By the time the 2010s began, music television was no longer the main source of new music information. MTV was still around, but it wasn’t as influential as it used to be. Music videos are still around. They moved to a new place. YouTube became the main platform for videos. It changed how videos were shared and how they were made.

Videos gained freedom when there were no limits on airtime or format. Some artists made their art bigger and more ambitious. Beyoncé used video as a way to express herself as an artist, not as a way to promote her music. Projects like Lemonade linked individual songs together using things like recurring images, locations, and themes. The images had a strong story behind them. They created context about race, gender, and intimacy without needing to use words. Viewers didn’t just watch a clip. They entered a sequence.

Other artists used video to explain one idea. Childish Gambino released “This Is America,” a song with striking images that invite close interpretation. The video spread quickly and was analyzed closely on social media. Its reach came from its density, not its polish. Meaning is revealed through comparison, surprise, and repetition, which is made stronger by online conversations than by traditional media commentary.

FKA twigs used a different visual language in her work. Her videos focused on the body as a way to express herself. They mixed dance, showing her true feelings, and control. Movement replaced storytelling. The camera focused on the effort, tension, and stillness. These videos didn’t become popular by being overly dramatic or sensational. They invited close attention and rewarded it with detail.

YouTube also changed how audiences engaged. View counts were public, and comments and shares happened instantly. Videos were shown with reaction clips, fan edits, and breakdowns. After a release was published, its ownership changed from the creator to the public. People started talking about it. Artists had to understand that other people would stop, rewind, and change the way they saw their images.

After MTV, music videos didn’t have a unified style. Some were like movies, while others were more natural. Some people try to be clear, while others like to be vague. They were connected by their function. Videos became places where people could watch music and see images together. They weren’t just random breaks in the programming. They were places that people wanted to visit. These places influenced how people remembered songs long after they first heard them.

Authenticity as Performance: The Paradox of Being Real

By the middle of the 2010s, being authentic was one of the most important qualities in popular music. Listeners wanted artists who felt real, close, and emotionally understandable. But this demand was strange. People no longer discovered authenticity over time. People expected it and said so in public.

Artists found different ways to deal with this tension. Lorde created a persona that was distant and exclusive. She didn’t talk too much. She wasn’t always sure about what to say. She also let silence be part of how she talked to people. People thought that the restraint was a sign of sincerity. People trusted her because she didn’t give them access whenever they wanted it. She was authentic because she had personal limits, not because she was open about everything.

Others focused on being close. Billie Eilish came onto the scene in a space where fans expected her to be emotionally open, but she was careful to control how she presented that openness. The interviews, visuals, and lyrics showed vulnerability without saying why or offering an excuse. Her tone suggested that she was comfortable with being uncomfortable. What felt honest was not confession, but consistency. The emotional tone remained consistent across different platforms.

For Frank Ocean, being real meant being quiet. His long breaks between releasing new music, rare public appearances, and limited communication with the public made people focus again on the music. When new work arrived, it felt deliberate and personal, not shaped by demand. The audience filled the silence with their own interpretations, turning the absence of words into something meaningful.

Social media made these choices more complicated. They rewarded people who interacted with them often and punished those who disappeared by making them less visible. Artists who shared more often seemed closer, but they risked being exhausted and misunderstood. A casual post can convey a message. If they don’t respond, it might seem like they’re avoiding the audience on purpose. Authenticity became a performance that was always being watched, influenced by what people expected as well as the performer’s own intentions.

Fans were involved in this process. They looked at things like tone, language, and timing. They also compared how an artist acts now with how they acted in the past. It was important to be consistent. People were suspicious of the sudden changes. Growth had to be visible but smooth. There was less space for private changes.

The 2010s did not invent performance in pop music, but they changed how big it was and how personal it felt. Being real no longer meant revealing everything. It meant managing visibility in a way that made sense on an emotional level. Authenticity is something that the artist and the audience create together. It is both fragile and powerful.

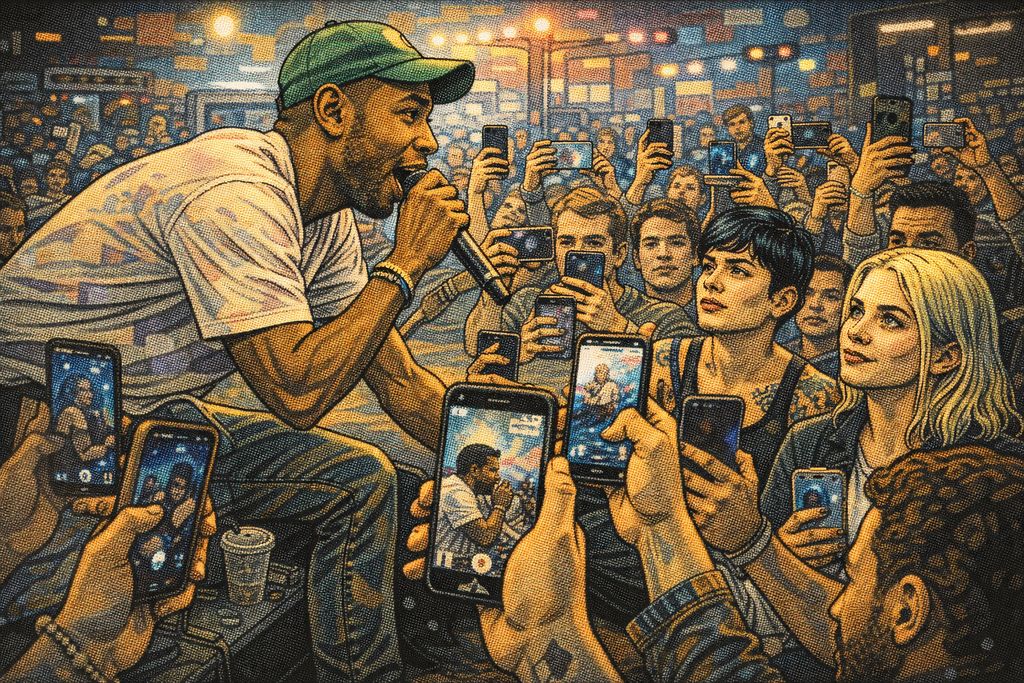

Hip-Hop's Rise: From Margins to Center Stage

Hip-hop didn’t take over popular music in the 2010s with just one big moment. It started slowly, but it became obvious that something was happening. What had long shaped culture from the margins moved into the center and stayed there. By the middle of the decade, hip-hop was the most influential genre, surpassing its status as just one of many. It was the first of its kind and influenced how much music is made today.

This change was not only about charts or visibility. Hip-hop reflected the conditions of the decade. It quickly adapted to streaming, liked releasing one song at a time, and did well working with other musicians. Its relationship with the internet developed naturally, not as part of a planned strategy. Online, scenes formed, and styles evolved in public. Listeners followed artists across projects instead of waiting for new albums to be released.

Hip-hop also reflected the social mood of the time. Questions about race, power, success, and vulnerability were directly expressed in the music, often without being softened or made less intense. Artists talked about the pressure they felt, their ambitions, and how they survive. The audience understood what they were talking about and didn’t treat them coldly.

Hip-hop moved from cultural force to cultural foundation in the 2010s, reshaping not only its own future but also the sound and structure of popular music overall.

Drake, Kendrick, J. Cole: Hip-Hop's New Center

Hip-hop’s rise to the center of the music industry was not just because of one stylistic shift. It came from a buildup. Years of cultural influence, entrepreneurial thinking, and audience loyalty finally came together with platforms that rewarded constant output and direct connection. By the 2010s, hip-hop no longer needed to appeal to other genres. The industry started using it.

Artists like Drake are a good example of this change. His work mixed rap, R&B, and pop music, but he still had credibility in the hip-hop community. Songs would easily go from being personal confessions to becoming popular songs on the radio. This would often happen in the same release. That flexibility matched a listening environment that was built around playlists rather than genres. Drake’s presence felt like it was always there, not like it was only there during certain times. He was always there, and that mattered.

A new kind of centrality emerged with Kendrick Lamar. His albums used hip-hop as a way to express literature and politics, focusing on stories and locations. Good Kid, M.A.A.D City and To Pimp a Butterfly showed that albums could still be important, even when other formats were losing popularity. Kendrick’s success showed that even in a fast-moving system, there was still room for depth and ambition.

J. Cole built his career around being consistent and producing his own music. His work didn’t follow trends. It focused on deep thinking, talking about class, doubt, and responsibility without using shock tactics. That approach was popular with listeners who wanted to think deeply instead of being distracted. Hip-hop’s popularity didn’t depend on just one voice. It was dependent on the range.

The industry followed these artists instead of helping them grow. Marketing strategies were changed. The release schedules were more flexible. Features became more important than promotions. Pop stars tried to gain credibility by working with hip-hop artists, while rap artists didn’t need pop approval to reach a wide audience.

Hip-hop also changed how people thought about authorship and credit. Producers, writers, and collaborators became more visible as part of creative ecosystems, rather than remaining behind the scenes. The genre has always focused on identity and perspective, which is similar to a decade that values personal expression.

By the end of the 2010s, it felt like calling hip-hop a genre was no longer enough. It was like an operating system for popular music. It changed the way songs were released, how musicians built their careers, and how fans listened to music. What was once outside the industry has now become its foundation.

Trap, SoundCloud Rap, and the DIY Pipeline

Hip-hop moved into the center of the industry, but new artists still found ways to push the boundaries. Trap music and the SoundCloud ecosystem developed differently than music usually does. Usually, music develops through labels, radio, or press. They grew together, moving quickly and spending time in the same online spaces. The result was a pipeline that felt messy, uneven, and full of life.

Trap music started in certain areas, especially the American South. However, it only became popular thanks to the internet. Producers and rappers shared ideas for music quickly. They would release music before it felt finished. This looseness became part of the sound. Heavy bass, short melodies, and repetitive structures were good for people who don’t pay much attention and people who are listening on their phones. Tracks worked instantly, even when they didn’t have much of a story.

Artists like Future helped create this style. He used melody, repetition, and emotional ambiguity to change how people thought about rap vocals. One could feel pain, act brave, and be detached all at the same time and in the same verse. That emotional blur resonated widely and influenced artists in many different genres.

Groups like Migos took trap music and changed it into a style that can be used in many different ways. They focused on rhythm, cadence, and vocal patterns that everyone could share. This made it easy for people to remember and reuse their songs. The music spread through short clips and social media, building momentum through repetition rather than explanation. Success felt like it was a group effort as well as an individual achievement.

SoundCloud made these changes happen faster. The platform let artists upload tracks right away, see how people reacted to them, and get more followers without the need for intermediaries. For listeners, it felt like they were discovering something new and unexpected. Before they had the right infrastructure, artists like Lil Uzi Vert and XXXTENTACION gained visibility on SoundCloud. Their rise showed how quickly people could pay attention to a voice that felt important, even when there weren’t many resources available.

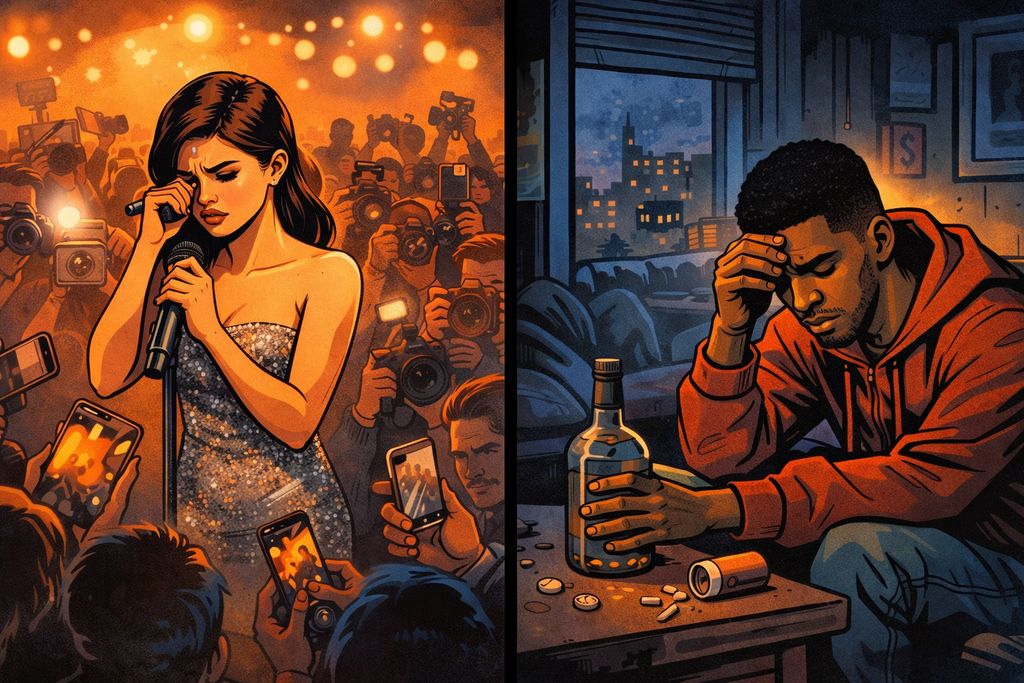

This pipeline came with real costs. Careers developed in public before artists had time to stabilize. Audience expectations grew faster than support systems. Artists were expected to release constantly, often at the expense of health and long-term craft. The same speed that enabled discovery also increased pressure and scrutiny.

But the impact was lasting. The Trap and SoundCloud cultures changed how labels found new talent, how producers worked together, and how audiences accepted mistakes. Anyone could start making music without having to refine their skills or get approval. It required presence. In the 2010s, that change allowed many people to share their ideas, even as it showed how easily success could be lost.

Nicki Minaj, Cardi B, Megan Thee Stallion: Women in Hip-Hop

Women in hip-hop entered the 2010s into a space that was highly visible, but still unequal. The genre became more popular, which brought in more viewers and started more conversations. But this did not automatically fix the problems of who gets credit, who has control, and how respect is given. The way those tensions were addressed changed. Now, artists and listeners talk about them more openly.

Nicki Minaj was a very important figure in the early 2010s. Her technical skill, vocal range, and ability to control her persona made it impossible to dismiss her as a novelty. She effortlessly shifted between aggressive rap performances and pop structures, never choosing one style over the other. People paid close attention to her, and often judged her based on her gender, which is something that male peers rarely experienced. Even so, her success came at the cost of her freedom.

Later in the decade, Cardi B used a different approach to become successful. Her rise was closely tied to her social media presence and her tendency to speak freely. She didn’t separate her personal story from how others saw her. Instead, she treated both as parts of the same voice. That openness connected with listeners who felt left out of the polished industry stories. Success came quickly, and it led to discussions about authenticity, social class, and taste that reflected larger cultural disagreements.

Megan Thee Stallion brought something new to the table. Her work was confident, funny, and clear. It also talked about education, independence, and self-definition. She made it clear who owned what and what the rules were, talking directly about contracts, credit, and control. Her presence meant that business conversations were more open and visible, rather than staying private and hidden.

These artists had different approaches, but they faced similar pressures. People judged sexual expression more harshly. People were more likely to question the authority of the government. When they were successful, people were suspicious of them instead of being happy for them. Hip-hop’s influence was so big that it gave these artists a voice that earlier generations rarely had.

Fans played an active role in shaping this environment. Support for the idea could have been strong and widespread, but the negative reactions to it also spread quickly. Online spaces can make praise and criticism seem louder. They can also make artists feel they have to respond or leave right away.

The 2010s did not solve the gender imbalance in hip-hop. They did change how visible things were. Women were no longer seen as exceptions to the genre’s rule. They were essential to its core, affecting the sound, language, and business practices. Power was still up for debate, but it was no longer hidden.

Electronic Music: EDM, Festivals, and the Dance Floor

Electronic music became more popular in the 2010s. Songs that were once played on nightclubs and late-night radio shows started being played on big stages at daytime festivals. What had started as something small that only a few people knew about now had hundreds of thousands of people listening to it. For a moment, electronic music seemed to be the language of young people. It was full of energy, release, and scope.

This visibility came with tension. EDM became popular, and electronic music became a central part of pop culture. However, it also made the differences between different types of electronic music less important. The different types of music were mixed together. Producers became the main focus. Drops replaced the gradual builds. For some listeners, this felt like a freedom. For some people, it felt like a loss.

At the same time, electronic music never fully left its roots. Even though there was a festival, local scenes kept changing, often in a quiet and planned way. Clubs, labels, and communities kept the old ways of trying new things and fighting against the status quo alive, even as most people’s attention moved to other things.

The electronic-music story of the 2010s sits between scale and intimacy: EDM changed public expectations, underground scenes answered back, and the genre kept moving between mass visibility and private spaces.

The EDM Boom: When Electronic Went Massive

The early and mid-2010s saw electronic dance music become a mainstream force. Festival lineups put DJs at the top, crowds grew larger each year, and electronic tracks became the most popular music on pop radio, which was surprising because electronic music wasn’t as popular ten years earlier. EDM offered a sense of scale that matched the moment. Big drops, simple builds, and clear emotional payoffs worked well in open-air spaces designed for spectacular shows.

Artists like Avicii were key in this change. His melodies were inspired by folk and pop music, which made electronic music more accessible to new listeners. Songs like “Levels” and “Wake Me Up” were popular in many different settings. They were played in clubs, on the radio, and at festivals. His success showed that electronic music can feel personal, even when it’s performed in front of a large audience.

Producers like Calvin Harris used collaborations to create EDM music. He worked closely with popular singers to create songs that could be played on the radio and still have the energy needed to get people to dance. The producer became a well-known figure, not just a background presence. Names mattered. Faces mattered. Electronic music started using the same style and image as pop music.

Festival culture made these changes even stronger. Events like Tomorrowland and Ultra made EDM a global experience. EDM is all about repetition and release. People from different countries came together to enjoy the same music and special moments. That sameness was part of what made it appealing. It was reliable, even though it was a time of great change.

But the limits of the boom became clear soon after. As the lineups became more similar, critics and longtime fans started to wonder what had been lost. The subtlety of the original design was replaced by a more predictable, formulaic approach. The sets were timed and designed to be as impactful as possible, which meant there was little room for error. Some producers felt like they had less creative freedom because they felt pressure to make hits.

People also started talking about the human cost. The tour schedule got more intense. People’s expectations grew. People’s personal boundaries were tested. The public saw endless celebration, but also saw exhaustion and isolation. Later in the decade, Avicii’s death led to difficult conversations about mental health, labor, and care within electronic music culture.

By the late 2010s, EDM wasn’t seen as unavoidable anymore. Its sounds were still around, but it was less influential in culture. What lasted was not the formula, but the lesson. Electronic music can fill huge spaces, but it can also get lost in those spaces. The boom showed that it was possible to make things bigger. Its decline made listeners remember why intimacy and experimentation were important.

Underground Resistance: Keeping Electronic Music Alive

While electronic dance music (EDM) was the main focus of festivals, underground electronic music continued to develop in its own way. These spaces did not completely reject visibility, but they did resist simplification. Clubs, small record labels, and local communities continued to focus on sound systems, long sets, and the gradual development of style. They had a quieter influence, but they were consistent.

Cities with strong electronic music scenes have either adapted or disappeared. Berlin kept a culture going that was all about long parties and not much else. DJs like Ben Klock are known for this approach. His sets focused more on the smooth transition from one beat to the next, drawing listeners into a steady change rather than a sudden, intense peak. The experience rewarded patience and close attention. This was very different from the festival structures.

Artists like Nina Kraviz gained credibility in underground scenes and also gained popularity more widely. Her work was hard to categorize. It mixed the physical intensity of techno with moments of vulnerability and weirdness. She spoke up for herself in different situations, showing that being visible doesn’t mean losing your individuality.

A more intense and edgy style emerged through artists like Helena Hauff. Her sound was a mix of electro, industrial, and early techno, with a preference for raw textures and analog imperfections. In a time when most music is produced in a smooth and polished way, this roughness felt like it was on purpose. It reminded listeners that electronic music has always been based on risk and uncertainty.

Underground spaces also kept social practices that festival culture often changed. Long sets let DJs respond to the crowd instead of following a set schedule. Clubs helped create communities where people regularly attended and behaved in a certain way. These environments preferred to keep things private instead of making a big deal out of them. The music was more important than the performer.

Online tools were also used, but in a different way. Platforms helped spread mixes and recordings, making local scenes more popular without replacing in-person events. Fans discovered artists online and then looked for places where they could hear their music.

The 2010s did not create as many different types of electronic music as there were in the past. Instead, they made the different types of electronic music more varied. EDM made electronic dance music more popular, while underground scenes kept the music focused on a small group of dedicated fans. They showed that electronic music could remain popular without losing its original style. The balance was delicate, but it lasted. It was kept going by communities that chose to be patient instead of trying to do too much.

Skrillex, Diplo, Deadmau5: Producers as Pop Stars

The 2010s changed how producers were seen and how they understood their own role. In the past, many producers worked behind the scenes. They were not well-known to the public. They worked on creating records. That balance changed. Producers became famous, worked with other people, and sometimes were the most interesting part of the show. Their names were well-known, and their sound was like a symbol of their style.

Artists like Skrillex are a good example of this. His rise made electronic production a topic of conversation among the public, both in terms of the sound and the persona. The music had clear features, like harsh textures and dramatic drops, that listeners could name and recognize. His work was a turning point where how a product was made became a way to sell it.

Others were more flexible when it came to authorship. Diplo easily switched between different types of music and worked with various artists. Instead of limiting his work to one type of sound, he connected different types of sounds together. The projects included pop, dancehall, hip-hop, and global club music. This shows that in that decade, the lines between different types of music were becoming more blurred. His presence showed a new kind of power that comes from having access to things and being able to adapt.

Producers like Deadmau5 used control and authorship in a different way. His work showed that he was an expert in his field and that his ideas were clear and consistent, often with a strong visual style. The producer was not just creating tracks, but building a whole world around them. Fans followed that world as much as the music itself.

This change had a big impact on the creative process. Producers spoke with labels, artists, and audiences directly. They toured as the main act, released albums under their own names, and maintained online presences that influenced how the public saw them. Some people found that having this freedom was good for them and made them feel safe and live long lives. Some people felt that it put pressure on them to be themselves and to be good at their craft at the same time.

At the same time, producer branding risked making collaboration less exciting. Electronic music has always been based on collaboration and innovation. When names became the most important thing, people sometimes stopped paying attention to the networks that made innovation possible. The creation of sounds is now seen as a form of intellectual property. This intellectual property is kept secret and not shared with others.

The decade did not resolve this tension. It exposed it. In the 2010s, producers worked as creators of sound and as important figures in a world where many people are competing for attention. Their work had a big impact on the sound of electronic music and how authorship was understood. In a culture where people have constant access to things, producers learned to balance being unique with sharing things, and being present with being careful.

Rock's Reinvention: Guitar Music Finds New Life

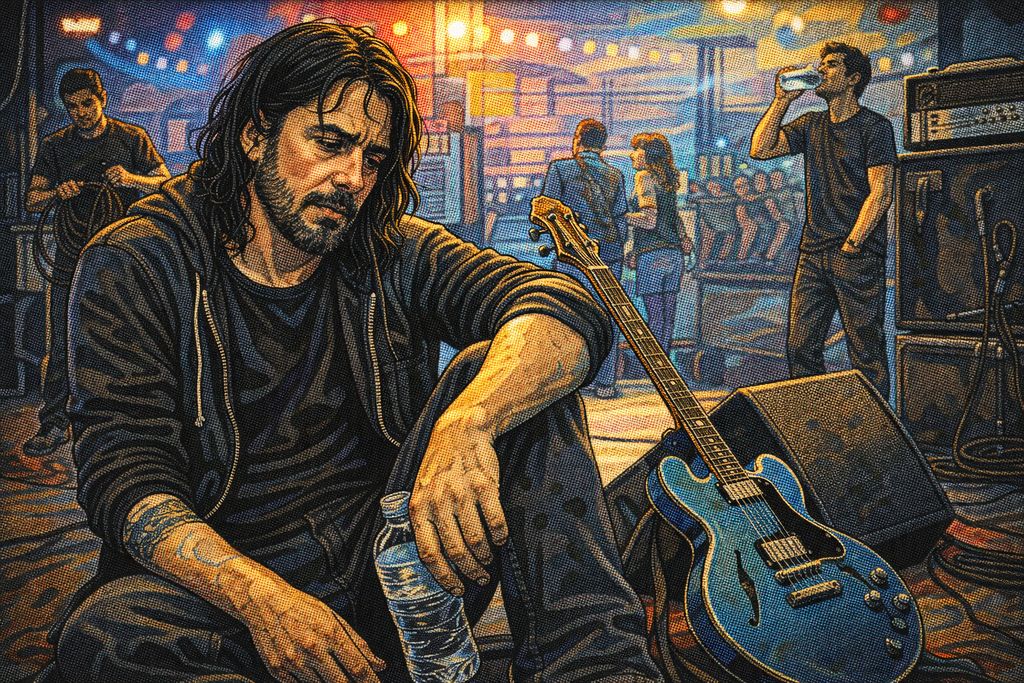

Rock music was still around in the 2010s. It moved out of the center and had to think again about what it meant to be relevant when it wasn’t always easy to see. For many years, music played on guitars had a big influence on the idea of what it means to be young, to be rebellious, and to be real. By the start of the 2010s, that position was no longer safe. Charts moved to a different place, and younger listeners often discovered rock music by listening to old recordings instead of new releases.

This change forced others to change too. Some bands decided to focus on touring and working with long-standing audiences, embracing their legacy status. Some musicians changed the style of rock music to fit the mood of a quieter, more reflective time. Instead of arguing, they chose to be intimate. The lyrics focused more on everyday uncertainties than on big, bold statements. Guitar music stopped trying to compete with pop and hip-hop music. Instead, it explored smaller, more personal spaces.

Digital platforms had a complicated role. They made rock music available to people who might not have heard it otherwise, and they also played other types of music that people could enjoy right away. Rock survived by becoming flexible, reflective, and selective about its goals.

Rock and alternative in the 2010s are best understood as adaptation: artists adjusted their sound, scale, and goals to stay meaningful in a new musical landscape.

Rock's Decline: When Charts Stopped Caring

By the early 2010s, rock’s relationship with the charts had already changed. Guitar-driven music still had fans, but it wasn’t as influential in popular culture as it once was. This change happened gradually. It wasn’t sudden, and it wasn’t just because one trend replaced another. It showed bigger changes in how music was shared and how listeners got used to it.

Rock bands like Foo Fighters kept releasing popular albums and performing at big festivals. Their presence showed that rock had not lost its audience. It no longer automatically appeared on the screen. Success depended more on touring, reputation, and long-term connections than on streaming numbers or viral moments. Many popular musicians use albums as a reason to go on tour again, instead of using them to make a big change in their style.

Younger rock bands had different challenges. In the early 2010s, groups like Kings of Leon had some success on the radio, but this was hard to keep up as people’s listening habits changed. Guitar music had a hard time being included on playlists that prioritized mood and immediacy over the full range of sounds. Long introductions, changing structures, and stories based on entire albums didn’t always fit the new logic.

Even bands with a large international fan base felt the change. Muse focused on being dramatic and big, with a strong live presence, and their songs were less important in showing how important they were. Rock’s power was more evident on stage than in the numbers. The live show was the main way to connect with others, and it offered an experience that streaming could not replace.

The media paid attention to the numbers. Hip-hop and pop music dominated the charts, and the media followed suit. Rock was often seen as something that was passed down from the past or a small group interest, instead of a continuous movement. This way of thinking influenced how people, especially younger listeners, saw rock music. These younger listeners learned about rock music through older albums instead of hearing new music from new artists.

Even though there was less of their work on the charts, it didn’t mean that they were all out of creative ideas. It made people think differently about what they expected. Rock no longer has to speak for everyone. It spoke for the people who used its language, whether through energy, reflection, or shared expression. The genre’s low visibility made it important to be clear. Rock in the 2010s survived not by trying to be the best, but by accepting its new role and finding strength in continuing what it had done in the past rather than trying to win new fans.

Indie's Turn: The National, Arctic Monkeys, and Emotional Honesty

As rock music lost popularity, indie and alternative music focused more on intimacy and connection than on being big and famous. In the 2010s, music that felt personal, conversational, and grounded in everyday feelings was popular. Instead of competing for attention by being loud or fast, many artists chose to be moderate. The songs played slowly. The lyrics talked about feeling unsure, remembering the past, and the small steps of getting through everyday life.

Bands like The National built their reputation on that same idea. Their music was characterized by slow tempos and thoughtful lyrics, often exploring themes related to adulthood, anxiety, and emotional distance. Albums didn’t chase down moments. They gained meaning over time. They found listeners who came back to them over and over again, instead of all at once. In a fast-changing world, that steadiness felt reassuring.

In other places, artists focused on small details to create intimacy. The band Arctic Monkeys changed their style a lot during the 2010s. They went from being cocky and confident to being more thoughtful and creative in their music. Records like AM and later Tranquility Base Hotel & Casino showed that the band was willing to question its own role and what its audience expected from it. The music was interesting but not predictable.

A new voice emerged through artists like Phoebe Bridgers. Bridgers’ work focused on emotional honesty without relying on shock tactics. Her songs spoke clearly about feeling sad, not knowing what will happen, and caring about others, often in a quiet voice. The writing felt closer, not smaller, because it wasn’t overly dramatized. The listeners could relate to the pauses and unfinished thoughts because they had experienced similar things.

Digital spaces made this shift towards honesty possible. Bedroom recordings, simple arrangements, and rough vocals spread quickly through streaming and social sharing. The intimacy felt right for late-night listening. Indie music didn’t have to compete for people’s attention. People liked it because they could recognize it without having to talk about it.

This change also changed how success was measured. The tours focused on theaters instead of arenas. People bond over shared feelings, not over where they come from. In the 2010s, indie and alternative music did not try to take the place of rock music. It offered something else. It was a way to listen that made room for vulnerability, patience, and the feeling that music could still meet listeners where they were, without asking them to be louder than they felt.

Legacy Acts: David Bowie, Radiohead, and the Streaming World

For artists who had built their careers long before the 2010s, the 2010s brought a different kind of challenge. The question was no longer how to stand out, but how to remain important in a musical environment that is always changing and focused on speed, playlists, and new trends. Old acts were known for their history. This history could make their work better or make it worse.

Some artists used the decade to think about their work instead of competing with other artists. David Bowie is a great example of this, especially with his album Blackstar. The album came out not long before his death, and it wasn’t full of nostalgia. The album’s sound was a mix of jazz, electronic music, and abstract songwriting. It showed aging as a kind of creative change, not a decline. The record reached people of all ages because it didn’t try to follow trends. Instead, it trusted its listeners to understand it on their own.

Others focused on maintaining their connection with their fans by touring and releasing new music on a limited basis. U2 started releasing music online, and they were still well-known all over the world. But they also saw that there were limits to how well they could reach people. Many people still liked their music, but people often talked about how it was distributed and what it meant to the band’s legacy instead of talking about new artistic directions. The band’s experience showed how even a huge reach could feel fragile when people’s attention shifted to something else.

Some musicians embraced the flexibility of digital release without giving up the traditional album format. Radiohead kept experimenting with the format, presentation, and sound. Albums like A Moon Shaped Pool were balanced. They showed restraint and structure. This was important because the decade often rewarded immediacy. Their work suggested that patience could still be an artistic strategy, even if it no longer defined the market.

Legacy artists also had to deal with changes in who was listening to their music. Younger audiences often heard them through playlists or recommendations, and they weren’t connected to the original cultural contexts. Listeners could find a song without knowing its history. In this case, the song’s texture (its sound) might be more important than the story behind it. Some musicians didn’t like this change. For some people, it meant being free from expectations.

The 2010s were a challenging time for established artists. Some people moved back, some people changed, and some people were shocked. The most compelling responses were the clearest. The key was to remember the past while making decisions in the present, not to relive it. In a decade of constant change, these artists showed that lasting in the entertainment industry doesn’t mean being relevant on every social media platform. It required being honest about who one was and having the courage to keep creating without trying to stay young.

The Sound of the 2010s: Intimacy and Minimalism

If the 2010s had a hard time picking a style, they did a better job of having a common attitude. The songs grew closer together, quieter, and more exposed. The focus of production shifted from big, flashy shows to creating a more realistic and emotionally precise experience. In the ’70s, musicians and singers had a big impact on their listeners. They recorded their music in rooms that were small, so the sound would be more personal. Silence, breathing, and restraint became ways to express yourself.

Technology made this possible without requiring everyone to have the same level of skill. Software that didn’t cost a lot and home studios allowed artists to shape sound the way they wanted. Decisions that used to feel like limitations became choices about how things look. A voice without a lot of energy, a drum sound that is not very loud, or a simple arrangement of instruments could have more impact than a full band playing music. People started listening to music with headphones and in private, and the music changed too.

Producers and songwriters responded by designing songs that revealed themselves slowly. Hooks did not always announce themselves. Choruses would often weaken instead of growing stronger. The emotion of the music was as important as the words.

The focus now turns to songwriting and production choices, and to why intimacy became one of the most powerful sounds of the 2010s.

Minimalism: When Silence Became the Loudest Sound

One of the most striking changes in the 2010s was that people started to like things that were simpler. Songs didn’t need to be loud to be good. Many artists chose to leave space open. They did this to allow silence and restraint to carry meaning. This approach did not suggest emptiness. It showed that the listener was trusted and that small details were important.

Artists like James Blake played a central role in shaping this attitude. His music often consisted of a few notes on the piano, short vocal phrases, and sudden quiet periods. The gaps between the notes were as important as the notes themselves. The song felt very personal, almost as if it could fall apart at any moment. That tension made it appealing.

A similar sensitivity appeared in the work of Frank Ocean. His albums focused more on creating a certain mood or atmosphere than on following a traditional structure. The music blended different types of sections, like spoken parts, melodies, and ambient passages, without being easy to define as either a verse or a chorus. This looseness encouraged listeners to focus on their feelings instead of following the structure. Silence was not empty space. It was a frame.

Later in the decade, Billie Eilish brought minimalism to the forefront of pop music. Songs with soft percussion, muted bass, and vocals almost too quiet to hear stood in contrast to the maximal energy that had dominated earlier years. Her recordings made listeners feel like she was talking directly to them, not just entertaining them. In the past, things that sounded unfinished might have been intentional. But here, it felt like it was done on purpose.

The production choices supported this closeness. Reverb was used in moderation. Vocals were usually close to the front, and they had a breathy, textured quality that wasn’t overpowered. The arrangement allowed people to interpret the emotions for themselves, instead of telling them how to feel. Headphones were the perfect way to listen to this music, making it a personal experience.

This shift towards minimalism was influenced by the overall trends of the decade. There was always noise, speed, and visibility. Because of this, quiet was rare and valuable. The music started to play more slowly and focused more intently. This led to a change in what people expected. In the 2010s, power did not always come from impact. It could arrive through pauses, through space, and through the decision to let a song speak softly without disappearing.

Autotune: From Correction to Emotional Expression

Autotune has been used in popular music for a long time, but it wasn’t until the 2010s that it became a common tool or a popular effect. During this decade, its role changed. Many artists didn’t hide their imperfections; they used them to create their art. The technology was used to create emotions, not to eliminate them.

One of the most important changes happened earlier, but its effects lasted well into the 2010s. Kanye West had already used autotune to show his true feelings instead of hiding them. That approach stuck around and changed over time. In the 2010s, autotune was no longer seen as something bad. It became a part of the voice. It added distance, fragility, or tension.

Artists like Future took advantage of this. The way he sang made it hard to hear the words and the music. It was like he was making a fog to show his feelings. Autotune made the edges less sharp and the expression less intense, but it still conveyed feelings of exhaustion, detachment, and pain. The listeners did not understand what was being said in Polish. They heard weariness through technology. That ambiguity had a big impact, influencing the sound of trap and other music.

Bon Iver used it in a different way. Autotune and digital manipulation changed the shape of vocals, often making language disappear into the background. The human voice was still there, but it sounded different. This change did not remove feeling. It gave it a different perspective, making it seem more emotional and reflective than direct.

Autotune is a tool that can be used in both pop and hip-hop music. It helps artists express ideas or feelings that are hard to put into words. It made a barrier between emotion and exposure. That buffer was important in a period of time when they were always in the public eye. Technology offered protection, but it did not remove emotion.

The listeners adapted quickly. People started to see autotune in a better light as they realized how well it could be used to express ideas. What sounded fake started to feel natural in the context of the decade. Software-shaped voices reflect lives influenced by platforms, screens, and technology.

The 2010s did not make autotune more common by hiding it. They made it okay by being honest about it. When used thoughtfully, it became a way to express uncertainty, exhaustion, and desire. It let artists speak in a way that was both close enough to be heard and far enough to feel safe.

Bedroom Production: Clairo, Rex Orange County, and Home Recording

The 2010s were defined not only by aesthetic choices but also by the physical spaces where they were created. Music started to be made not just in expensive studios but also in people’s bedrooms, shared apartments, and other places where they could make it on their own. This change did more than lower costs. It changed how songs felt. The recordings had the same feel as the rooms where they were made. As a result, listeners could hear that closeness as part of the message.

Artists like Clairo are known for this style. Early recordings were simple. They had soft vocals and basic music. Their appeal was that they were immediate. Songs felt like private thoughts shared quietly, not performances designed to be heard from far away. That tone fit naturally into streaming culture, where people often listened to music by themselves.

A similar level of intimacy was seen in Rex Orange County’s work. His music mixed pop, jazz, and indie styles without making everything sound too smooth. The singer’s voice was sometimes close in the mix and sometimes uneven, and sometimes the singer sounded a bit unsure. The production did not correct these problems. It made them look good. People’s feelings became more obvious, rather than staying hidden.

For musicians like Troye Sivan, making music in their bedrooms allowed them to connect directly with their fans while also thinking about who they were as people. Songs talked about wanting things, how people see themselves, and being open and honest. They did this in a careful way. The production choices matched that tone, choosing clarity and warmth over strong effects. The feeling of intimacy was deliberate, not random.

Technology made this approach possible, but it didn’t guarantee success. The important thing was how artists used it. Many people did not want to make too much, and they let mistakes and pauses stay in the work. These details made the music feel more real. The listener could picture where the song was made, and often it was a place that reminded them of their own life.

This close relationship led to certain expectations. Loudness and perfection lost their importance. People started to believe what they were feeling. The listeners weren’t expecting big promises. They expected honesty, even when it wasn’t finished. Bedroom production was an easy way to meet that expectation without any of the usual fuss.