When Heavy Music Found Its Female Voice

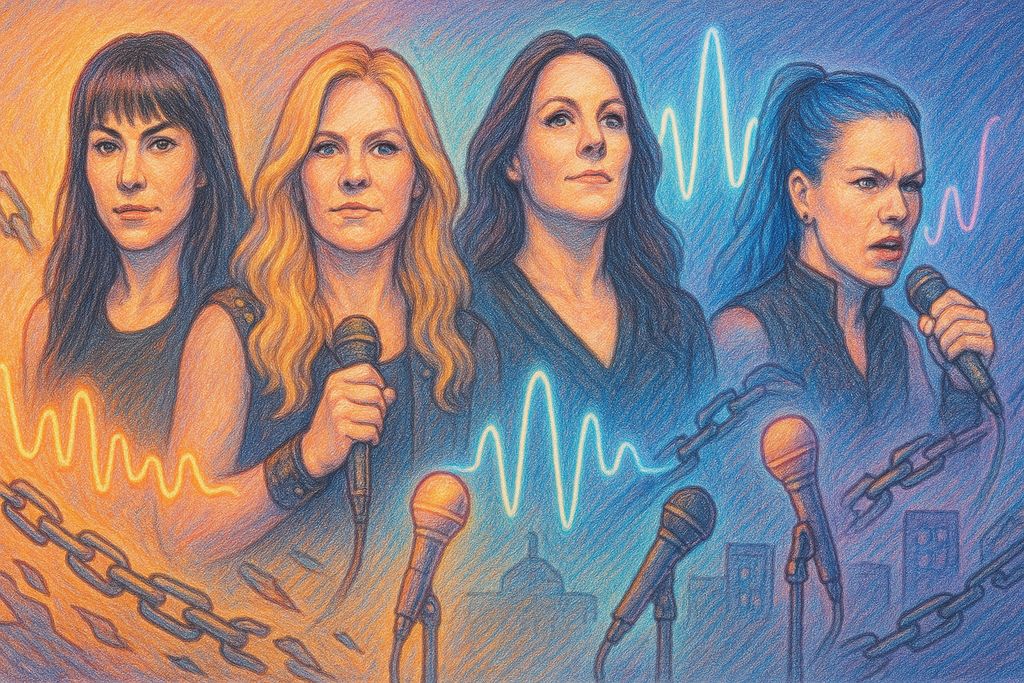

Heavy rock and metal did not grow up expecting female voices at the front. For decades, the genre was shaped by loudness, physical endurance, and a narrow idea of who was supposed to own the stage. Women were present from early on, but often treated as exceptions, novelties, or visual add-ons rather than full artistic forces. The discussion starts from that imbalance and works outward, without romance or myth-making.

Female rock and metal vocalists did not enter an empty space. They stepped into rehearsal rooms, tour buses, studios, and press cycles that were already defined by rigid expectations. Some were pushed toward polished looks, others questioned for sounding too aggressive, too emotional, or simply too visible. Yet they stayed, adapted, and reshaped the sound from the inside.

This is not a celebration built on slogans. It is a close look at work. At voices trained under pressure. At careers built through resistance, compromise, and persistence. The focus here is rock and metal as working environments, not fantasy worlds. Artists, songs, albums, conflicts, and consequences are named clearly, based on verifiable history.

The sections ahead offer a grounded account of how female voices became impossible to ignore in heavy music, not by permission, but by presence.

Barriers, Bias and the Early Years

Industry Resistance and Gender Roles

Rock and metal did not simply overlook women. They actively resisted them. From the late 1960s onward, the industry surrounding heavy music was built on assumptions about strength, authority, and control that were coded as male. Loud guitars, long tours, physical stamina, and technical dominance were framed as proof of masculinity. A woman stepping into that space was rarely judged by the same standards as her male peers.

Record labels often treated female-fronted bands as risky investments. Executives questioned whether audiences would accept aggressive or commanding female voices in heavy music. Promoters worried about touring logistics. Journalists asked different questions in interviews. Instead of songwriting or vocal range, women were asked about appearance, relationships, or whether they felt “comfortable” on stage. The message was subtle but consistent. You are a guest here.

This bias shaped early career paths. Many female vocalists were encouraged to soften their sound, to sing cleaner, sweeter, or more restrained than the music demanded. Others were pushed toward hypersexualized imagery to justify their presence visually, even when the music itself was raw or confrontational. In both cases, the focus shifted away from musical labor. Competence had to be proven repeatedly, while mistakes were amplified.

Touring exposed these inequalities even more clearly. Shared buses, cramped venues, and male-dominated crews created environments where boundaries were often ignored. Women were expected to adapt, stay silent, or tolerate behavior that would later be openly criticized. Speaking up carried risks. Bands could lose support. Contracts could quietly disappear. Silence was often framed as professionalism.

Radio and press coverage reinforced the pattern. Heavy music magazines regularly framed female artists as trends rather than contributors. Phrases like “female-fronted rock” appeared less as descriptors and more as warnings, signaling difference instead of belonging. Male singers were reviewed as musicians. Female singers were reviewed as concepts.

Despite this, women continued to enter the scene. Not because doors were open, but because the music demanded it. Many started in local circuits, smaller clubs, or independent scenes where gatekeeping was weaker. Some learned to self-manage early, handling promotion, bookings, and creative direction themselves. Others accepted compromises in order to gain visibility, then slowly reclaimed control.

The importance of this period lies not just in exclusion, but in adaptation. Female vocalists learned to navigate an industry that rarely met them halfway. They built resilience long before it was celebrated. By the time some of them reached wider recognition, they were already seasoned professionals, shaped by resistance rather than support.

That groundwork explains what followed. The breakthroughs of later decades did not appear suddenly. They were earned in rehearsal rooms where expectations were low, in interviews that underestimated them, and on stages where they had to prove, again and again, that heavy music could carry female voices without losing its force.

Early Rock Pioneers Who Broke Through

Long before female-fronted metal became a recognizable category, a small group of women forced their way into heavy rock by doing the work, night after night, without guarantees. They were not framed as movements or symbols at the time. They were musicians trying to survive in an industry that had little interest in making space for them.

One of the earliest and most visible figures was Suzi Quatro. Emerging in the early 1970s, she combined a raw rock voice with an assertive stage presence and, crucially, her own bass playing. Songs like “Can the Can” and “48 Crash” were not softened for radio comfort. They were loud, driving, and unapologetic. Quatro’s influence went far beyond chart success. She proved that a woman could front a hard rock act without surrendering authority or musical control. Many later artists would cite her as proof that visibility was possible.

Around the same time, Ann Wilson helped redefine what power could sound like in rock music. With Heart, she brought a wide vocal range that moved effortlessly between tenderness and force. Tracks such as “Barracuda” and “Crazy on You” showed that technical control and emotional intensity were not opposites. Wilson’s voice carried weight without aggression for its own sake, challenging the idea that heaviness required a specific kind of vocal roughness. Her success also exposed contradictions in media coverage, where musical excellence often competed with commentary on gender and image.

Another key figure was Joan Jett, whose approach rejected polish entirely. Coming out of the punk-influenced Los Angeles scene, Jett’s sound was direct and confrontational. With The Runaways and later as a solo artist, she embraced simplicity as strength. Songs like “Bad Reputation” and “I Love Rock ’n’ Roll” were built on attitude, rhythm, and refusal. Jett did not attempt to fit existing expectations. Instead, she narrowed the gap between punk and hard rock, opening space for women who did not want to perform refinement or vocal elegance.

Pat Benatar added another dimension to early heavy rock visibility. Trained vocally and grounded in classic rock structures, she combined technical skill with sharp, controlled delivery. Tracks like “Heartbreaker” and “Hit Me with Your Best Shot” carried aggression without chaos. Benatar’s success on radio and MTV created broader exposure, but it also highlighted a persistent tension. Female artists who achieved mainstream recognition were often treated as exceptions rather than indicators of change.

These pioneers were united less by a shared sound than by a shared condition. Each operated under heightened scrutiny. Mistakes were magnified. Success was framed as novelty. Longevity was questioned. Yet they endured, not by conforming, but by insisting on their right to occupy space in loud music.

Their impact cannot be measured only by sales or awards. They normalized the idea that women could belong on heavy stages without explanation. Later generations would enter scenes shaped, however subtly, by these early disruptions. The door was not opened fully, but it was cracked wide enough to push through.

The 1980s: Heavy Metal, Glam and Visibility

MTV, Image Control and Commercial Pressure

The 1980s changed the rules of rock and metal visibility almost overnight. With the rise of MTV, sound was no longer enough. Image became currency. For female vocalists, this shift created both opportunity and constraint, often at the same time.

Heavy music entered living rooms through television, and visual storytelling began to shape careers as strongly as songwriting. Record labels quickly understood the power of the screen. Bands were marketed not only by how they sounded, but by how they looked in motion. For male artists, this often meant exaggeration. For women, it meant negotiation. Female vocalists were expected to fit a narrow visual frame that balanced approachability with provocation, toughness with attractiveness. Falling outside that frame could limit airplay, regardless of musical quality.

This period introduced a subtle but persistent form of control. Women were rarely told outright that their music was insufficient. Instead, suggestions arrived wrapped in marketing language. Different wardrobe choices. Softer lighting. A more “relatable” persona. These adjustments were presented as practical steps toward success, not artistic compromises. Over time, the line between image and identity blurred.

Glam metal intensified these pressures. The genre itself played with gender expression, but not equally. While male performers could adopt makeup and flamboyance as spectacle, female artists were often confined to sexualized roles that reinforced traditional power dynamics. The visual freedom celebrated on stage did not extend evenly behind the scenes. Management decisions still reflected conservative assumptions about what audiences would accept from women in heavy music.

MTV exposure also reshaped public perception. Female vocalists became more recognizable, but recognition did not always translate into respect. Interviews focused on style before substance. Press narratives highlighted appearance over process. A strong voice could be overshadowed by a single outfit or camera angle. For many artists, this created a constant need to redirect attention back to the work itself.

Touring during this era added another layer of complexity. Larger stages and bigger audiences brought professional crews and improved infrastructure, but also intensified scrutiny. Every performance was potentially recorded, photographed, and replayed. Mistakes lingered longer. Experimentation became riskier. The margin for error narrowed, especially for women whose credibility was still considered fragile.

Yet the 1980s were not only restrictive. Visibility mattered. Seeing women front heavy bands on mainstream television altered expectations, even when the framing was imperfect. Younger musicians watching from bedrooms and rehearsal spaces absorbed these images differently. They saw possibility where critics saw novelty. The presence of female vocalists on global platforms challenged the idea that heaviness belonged to one voice type or one gender.

This decade was defined by tension. Exposure without autonomy. Opportunity paired with surveillance. Some artists embraced the system and used it strategically. Others resisted quietly, focusing on live performance and musicianship as anchors of control. Both approaches carried costs.

Understanding this era requires holding these contradictions together. MTV did not create female rock and metal vocalists, but it reshaped how they were seen, sold, and judged. The visibility of the 1980s opened doors, but it also built new walls, ones that many artists would spend years learning how to climb.

Defining Female Voices of 80s Hard Rock & Metal

By the mid-1980s, female voices in hard rock and metal were no longer rare sightings. They were still outnumbered, still questioned, but they had become audible in a way that could not be dismissed as coincidence. What defined this period was not a single sound, but a shared insistence on authority. These artists did not soften heavy music. They occupied it.

In continental Europe, Doro Pesch emerged as one of the most enduring figures of the decade. As the frontwoman of Warlock, she carried a rasped, forceful vocal style that aligned closely with traditional heavy metal rather than hard rock crossover. Albums like True as Steel and Triumph and Agony placed her voice at the center of martial riffs and anthemic choruses. Doro’s presence was significant not because she adapted to the genre, but because she matched it on its own terms. Touring relentlessly across Europe and the United States, she built credibility through consistency. Her career would later outlast many of her male contemporaries, reinforcing the idea that longevity, not novelty, was the real measure of success.

In the United States, Lita Ford carved out a different path. Already known as a guitarist from The Runaways, Ford transitioned into a solo career that balanced heavy riffs with commercial ambition. Songs like “Kiss Me Deadly” and “Close My Eyes Forever” brought her to mainstream attention, particularly through MTV rotation. Yet Ford’s work often sat at the intersection of control and compromise. While her guitar playing was central to her identity, marketing strategies leaned heavily on image. The tension between musicianship and presentation became part of her public narrative, reflecting broader industry patterns rather than individual choices alone.

Canada contributed its own hard rock force in Lee Aaron, whose career revealed how regional scenes shaped opportunity. Aaron’s early work leaned toward heavy metal before gradually shifting into hard rock with broader appeal. Albums such as Metal Queen and Whatcha Do to My Body showcased a strong, clear vocal delivery that avoided gimmicks. In Canadian rock culture, she achieved sustained visibility, even as international recognition remained uneven. Her career highlights how geography influenced which voices crossed borders and which remained locally celebrated.

In the United Kingdom, Kim McAuliffe and her band Girlschool represented a different model altogether. Closely associated with the New Wave of British Heavy Metal, Girlschool operated as a full band rather than a vehicle built around a single frontwoman. Songs like “Hit and Run” emphasized speed, grit, and collective energy. McAuliffe’s vocal delivery was raw and direct, fitting seamlessly into the scene rather than standing apart from it. Their collaboration with Motörhead and consistent touring schedule placed them firmly inside the metal ecosystem, not on its margins.

These artists were connected less by uniformity than by positioning. Each navigated a different balance between visibility and autonomy. Some embraced mainstream exposure. Others stayed closer to underground circuits. All faced the same underlying question. Could a woman front heavy music without explanation or justification?

The answer, in practice, was yes. But it came with conditions. Media narratives continued to frame these artists as exceptions. Reviews often emphasized gender before sound. Success was measured against novelty rather than craft. Yet within fan communities and live settings, perceptions were more direct. A powerful performance mattered more than a headline.

Live concerts played a crucial role in this shift. On stage, authority was immediate. A strong vocal cut through assumptions faster than any interview. Many female vocalists of the 1980s built their reputations through relentless touring, using performance as the most honest form of argument. Night after night, they proved that heaviness did not require permission.

By the end of the decade, female rock and metal vocalists were no longer isolated figures. They had become reference points. Younger musicians entering the 1990s would do so with these examples in mind, aware that the path remained difficult, but also knowing it had been walked before. The voices of the 1980s did not resolve inequality, but they reshaped expectations. And in heavy music, expectations matter.

The 1990s: Alternative Metal, Anger and Identity

Between Grunge, Alternative and Metal

The 1990s disrupted the visual excess and rigid hierarchies of the previous decade. Grunge, alternative rock, and emerging forms of alternative metal shifted attention away from spectacle and toward mood, tension, and emotional honesty. For female vocalists, this shift offered a different kind of entry point into heavy music, one that relied less on polish and more on presence.

The boundaries between genres blurred quickly. Bands moved freely between metal, punk, and alternative rock, often within the same album. This created space for voices that did not fit traditional heavy metal expectations. Aggression was no longer defined solely by volume or speed. It could be internal, fractured, restrained, or explosive in short bursts. Female vocalists used this flexibility to challenge older assumptions about how heaviness should sound.

At the same time, grunge’s cultural dominance complicated visibility. While the scene rejected glam aesthetics and commercial artifice, it was still shaped by familiar gender dynamics. Female artists were often pulled into simplified narratives, framed as emotional counterparts to male anger rather than as independent creative forces. The industry continued to categorize rather than listen closely.

Within this environment, alternative metal became a crucial bridge. Bands began combining downtuned guitars and heavy rhythms with melodic or unconventional vocal approaches. This hybrid space allowed women to lead without constantly defending their legitimacy. The music itself resisted clear labels, which weakened gatekeeping. If a band did not fit neatly into a genre box, expectations loosened.

The decade also saw a shift in lyrical focus. Instead of fantasy or theatrical rebellion, many songs explored alienation, identity, trauma, and social pressure. Female vocalists were often expected to embody vulnerability, but many inverted that expectation. They expressed anger without apology, sadness without fragility, and strength without posturing. The result was a more complex emotional register than earlier hard rock models had allowed.

Live performance remained central. Smaller venues, festival circuits, and alternative touring networks reduced some of the structural barriers seen in the 1980s. While sexism did not disappear, the cultural emphasis on authenticity created moments where sound outweighed stereotype. A compelling performance could still reframe assumptions, especially in scenes that valued intensity over image.

Importantly, the 1990s also marked a generational shift among listeners. Younger audiences were less invested in traditional rock hierarchies and more open to hybrid identities. Seeing women front heavy or semi-heavy bands became less surprising, even if it was not yet normalized. The question was no longer whether women belonged in loud music, but how their voices reshaped it.

This transitional space matters because it set the emotional and structural groundwork for what followed. The 1990s did not fully resolve the tensions between gender, genre, and authority in heavy music. But it loosened the framework enough to allow new forms of expression. The female vocalists who emerged during this time were not inheriting a stable tradition. They were helping to redefine what heavy music could sound like when it stopped insisting on a single voice.

Voices That Redefined Intensity

In the 1990s, intensity in heavy and alternative music stopped being a single emotion. It fractured into anger, irony, vulnerability, and confrontation, sometimes within the same song. Female vocalists who broke through during this period did not follow one model. What connected them was their refusal to perform intensity in expected ways.

One of the most visible and controversial figures of the decade was Courtney Love. As the vocalist of Hole, Love stood at an unstable intersection between grunge, punk, and alternative metal-adjacent heaviness. Albums like Live Through This paired abrasive guitar work with lyrics that confronted sexism, bodily autonomy, and media obsession head-on. Love’s voice was raw, often intentionally unpolished, and emotionally volatile. Critical reception rarely separated the music from her personal life. This conflation became part of her public burden. Yet musically, her work challenged the idea that female rage needed refinement to be taken seriously. The discomfort she generated was not a byproduct. It was the point.

In the United Kingdom, Skin offered a very different form of intensity. Fronting Skunk Anansie, Skin combined a powerful vocal range with a controlled, theatrical delivery that moved between softness and aggression without warning. Songs like “Weak” and “Selling Jesus” confronted political and social themes directly, often addressing racism, sexuality, and identity. Skin’s presence on stage was commanding, not confrontational for shock value, but rooted in clarity and confidence. As a Black, openly queer woman leading a heavy band in the 1990s, her visibility carried political weight, even when the music refused to be reduced to slogans.

Another crucial figure was Cristina Scabbia, whose early work with Lacuna Coil emerged from the European alternative metal scene at the end of the decade. Unlike many of her predecessors, Scabbia’s approach emphasized contrast. Her clean, melodic vocals often interacted with harsher male counterparts, creating tension within the songs themselves. This duality became a defining feature of the band’s sound. Rather than presenting intensity as constant aggression, Lacuna Coil explored atmosphere, restraint, and emotional layering. Scabbia’s role demonstrated that heaviness could exist without vocal abrasion, as long as emotional commitment remained intact.

These artists were often discussed in relation to male peers, rather than on their own terms. Courtney Love was framed through association and scandal. Skin was treated as an exception within alternative rock. Cristina Scabbia was frequently labeled through her gender before her musicianship. Yet their work expanded the vocabulary of heavy music in measurable ways. They altered how tension was built, how vulnerability functioned, and how authority could sound.

Media narratives during this period remained uneven. Reviews often focused on emotional expression as a gendered trait, praising intensity while questioning control. Aggression from male vocalists was framed as authenticity. From women, it was scrutinized for excess or instability. Despite this, fan reception often told a different story. Live audiences responded directly to performance, not framing. A convincing voice cut through skepticism quickly.

The 1990s stood out for their contradictions. Female vocalists were more visible than before, but also more exposed to public judgment. Their work was less likely to be dismissed outright, but more likely to be dissected personally. The pressure shifted rather than disappeared.

By the end of the decade, the groundwork was set for the next transformation. Heavy music was ready for voices that combined power with precision, aggression with technical control, and emotion with scale. The artists of the 1990s did not solve the problem of representation, but they expanded the emotional range of heavy music in ways that could not be reversed.

The 2000s: Symphonic Metal, Nu Metal and Emotional Extremes

Symphonic Metal and Classical Authority

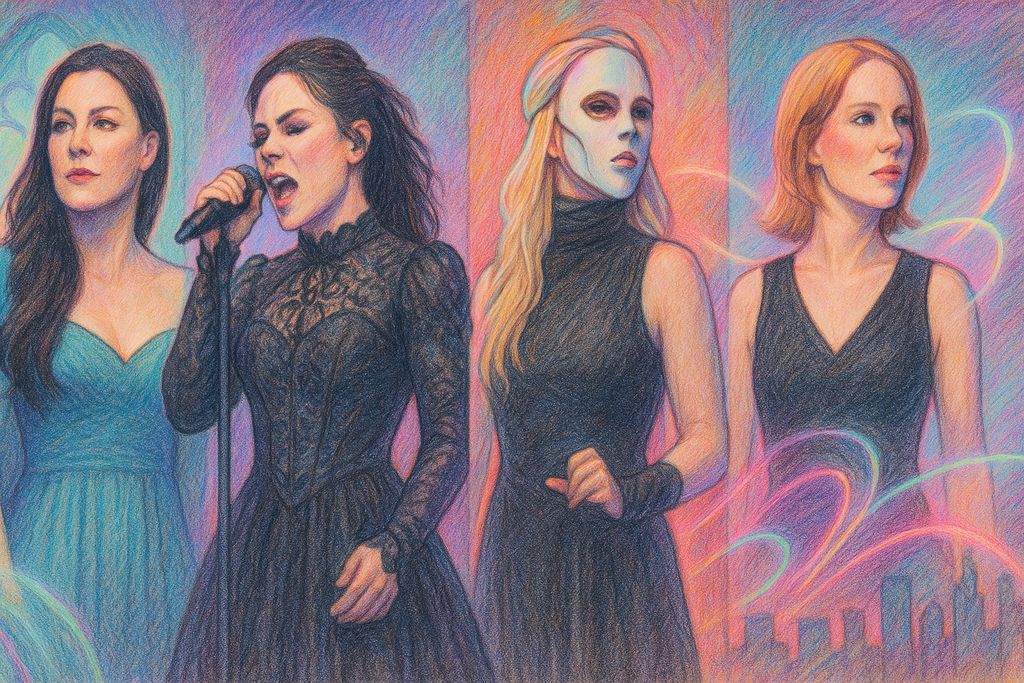

The early 2000s marked a turning point for female visibility in heavy music, particularly through the rise of symphonic metal. This subgenre combined heavy guitar work with orchestral arrangements, choirs, and classically influenced structures. For many female vocalists, it created a space where technical authority was not only accepted, but expected. Power was no longer measured solely by distortion or aggression. It was measured by control.

At the center of this shift stood Tarja Turunen, whose work with Nightwish reshaped global expectations. Trained in classical singing, Turunen brought operatic technique into a metal context without dilution. Albums such as Oceanborn and Once placed her voice above dense arrangements, not as ornament, but as a structural anchor. Her delivery was disciplined, resonant, and unwavering, even under the pressure of long tours and large festival stages. The success of Nightwish in Europe and beyond demonstrated that female vocal authority could scale up without compromise.

Yet Turunen’s prominence also exposed structural tensions. As Nightwish grew, media narratives increasingly framed the band through her image, often ignoring the collective nature of the project. Internal conflicts eventually led to her departure in 2005, a split that was publicly dissected and frequently oversimplified. The episode revealed how quickly admiration could turn into scrutiny when power dynamics shifted. Artistic control, visibility, and authorship became contested ground.

In the Netherlands, Sharon den Adel developed a contrasting model of symphonic metal leadership. Within Temptation evolved from gothic metal roots into a more cinematic sound, blending heaviness with accessibility. Den Adel’s voice carried clarity rather than operatic force, allowing emotion to surface without theatrical excess. Albums like Mother Earth and The Silent Force balanced narrative songwriting with broad appeal, helping the band reach audiences far beyond traditional metal circles. Her role emphasized collaboration over dominance, offering a different vision of authority grounded in cohesion.

A further evolution emerged with Simone Simons, whose work with Epica pushed symphonic metal toward greater complexity. Simons combined classical technique with modern phrasing, navigating rapid shifts between intimacy and scale. Epica’s compositions often addressed philosophical and political themes, demanding precision and stamina from their vocal arrangements. Simons’ performance style reflected a generation that inherited symphonic metal as a given, not an experiment. The question was no longer whether a woman could lead such music, but how far it could be taken.

They were united less by uniformity than by credibility. Classical training, rehearsal discipline, and endurance under touring conditions positioned them as professionals in environments that valued precision. Their voices were not treated as decorative contrasts to heavy guitars. They were integral to the architecture of the music.

At the same time, symphonic metal introduced new expectations. Female vocalists were sometimes boxed into narrow definitions of elegance or purity, replacing older stereotypes with subtler ones. The association between women and orchestral beauty risked becoming another constraint. Not every singer wanted or needed classical framing. Still, the genre expanded the sonic and cultural space available to women in metal.

By the mid-2000s, symphonic metal had achieved global reach. Festivals featured female-led bands as headliners, not curiosities. Audiences learned to associate heaviness with complexity rather than rawness alone. The authority established during this period would influence how female vocalists were received across other metal subgenres, including those that rejected orchestration entirely.

The rise of symphonic metal did not end debate or imbalance. But it shifted the center of gravity. Female voices were no longer arguing for inclusion. They were setting the terms.

Nu Metal, Alternative Metal and Inner Conflict

While symphonic metal emphasized structure and scale, another branch of heavy music in the 2000s turned inward. Nu metal and alternative metal focused on emotional fracture, psychological pressure, and personal narrative. The music was often less concerned with virtuosity and more with impact. For female vocalists, this space offered visibility, but also intense scrutiny.

A central figure of this era was Amy Lee, whose work with Evanescence brought a distinctly female perspective into a genre dominated by masculine aggression. Lee’s classically influenced piano background shaped the band’s sound, but it was her vocal delivery that carried emotional weight. Songs like “Bring Me to Life” and “My Immortal” combined vulnerability with controlled power, resisting the flattened anger typical of much nu metal at the time. Commercial success came quickly, but it arrived with constraints. Media narratives often reduced Evanescence to a visual brand or emotional stereotype, ignoring Lee’s role as a primary songwriter. Legal disputes with former band members later exposed the extent to which control over creative direction had been contested behind the scenes.

Nu metal’s broader culture created uneven terrain. The genre often leaned into hypermasculinity, emotional volatility, and public confession, yet female participation was frequently framed as contrast rather than contribution. Women were positioned as emotional anchors or melodic relief within aggressive soundscapes. Those who led bands outright had to navigate expectations that pulled in opposite directions. Too soft meant inauthentic. Too forceful meant unfeminine.

In Europe, Cristina Scabbia became a key figure bridging alternative metal and gothic influence. Lacuna Coil’s international breakthrough in the early 2000s relied on dynamic contrast rather than emotional overload. Scabbia’s clean vocals interacted with heavier elements without being subsumed by them. Albums like Comalies demonstrated that restraint could coexist with heaviness. Her presence also complicated gendered assumptions within metal. Scabbia was neither positioned as a victim nor as a spectacle. She functioned as a stable center within a collaborative band structure, which helped the group sustain a long-term career.

The American hard rock scene introduced another voice that would grow in prominence over the decade. Lzzy Hale emerged with a style that drew from classic rock aggression while addressing contemporary themes. Hale’s vocal approach combined grit, range, and a refusal to soften delivery for mass appeal. Early Halestorm releases leaned toward hard rock, but her performance style resonated strongly within modern metal contexts as well. Hale openly discussed vocal health, touring exhaustion, and industry pressure, offering transparency rarely afforded to female artists at the time. Her later role as a visible advocate for women in rock would build on foundations laid during this period.

This era was marked by exposure at scale. Radio play, festival slots, and mainstream press attention placed female vocalists in constant public view. Emotional expression became a selling point, but it also invited judgment. Lyrics about pain or vulnerability were often framed as confessional in ways that male equivalents were not. Strength was measured differently. Control was questioned more often.

Despite this, the 2000s solidified the idea that female-led heavy bands could sustain commercial success without being anomalies. Audiences grew accustomed to hearing women express anger, grief, and desire within distorted frameworks. The novelty faded, even if resistance remained.

Nu metal and alternative metal did not offer freedom without cost. Artists paid for visibility with overexposure, misinterpretation, and long-term pressure. Yet they expanded the emotional vocabulary of heavy music. They proved that intensity could be intimate, that heaviness could carry fragility without losing force, and that female voices could occupy the center of that contradiction.

By the end of the decade, the path forward had widened. Technical authority, emotional complexity, and genre hybridity were no longer competing ideas. They coexisted. The next wave of female vocalists would inherit a scene shaped by both the breakthroughs and the burdens of this period.

The 2010s and 2020s: Headliners, Hybrids and New Gateways

The 2010s shifted visibility again. Streaming platforms, YouTube, and social media reduced dependence on radio and labels. A song could travel worldwide before a full album existed, and live session videos became part of how fans judged credibility.

Floor Jansen’s timeline is a clear marker of this era. She joined Nightwish as a live vocalist in 2012, became a permanent member in 2013, and led the band on albums like Endless Forms Most Beautiful in 2015 and Human. :II: Nature. in 2020. That arc showed how an established singer could step into a global band, keep her own identity, and still drive a new creative phase.

A similar shift happened in extreme metal. Alissa White-Gluz joined Arch Enemy in 2014, fronting War Eternal that same year. The band followed with Will to Power in 2017 and Deceivers in 2022, proving that female harsh vocals could carry long-term momentum in a genre that often resists change.

Digital breakout moments mattered more than ever. Jinjer’s live session of “Pisces” in 2017 spread rapidly and positioned Tatiana Shmayluk as one of the most recognized extreme vocalists of the decade. The track comes from the 2016 album King of Everything, and the clip made the band visible far beyond the European circuit. Spiritbox formed in 2017, released the breakthrough single “Holy Roller” in 2020, and followed with the debut album Eternal Blue in 2021. Courtney LaPlante’s mix of clean melody and harsh technique became a blueprint for modern metal hybrids that live online as much as on stage.

Mainstream rock spaces also kept opening. In This Moment’s Blood in 2012 and Black Widow in 2014 reinforced Maria Brink’s approach to theatrical staging and visual control. Halestorm marked another milestone when “Love Bites (So Do I)” won the Grammy for Best Hard Rock and Metal Performance in 2013, a rare award recognition for a female-fronted hard rock band. Evanescence returned with The Bitter Truth in 2021, their first studio album since 2011, showing how long-running acts could reenter the cycle without being treated as nostalgia.

European scenes remained strong throughout the decade. Within Temptation released Resist in 2019 and continued touring on a scale that matched their earlier success. Lacuna Coil’s Black Anima arrived in 2019, reaffirming that a veteran band could still deliver heavy, modern material while keeping its identity intact.

These years brought more women into festival headlines and international touring circuits. Bias did not disappear, but the volume of examples made it harder to treat female voices as exceptions. The result is a wider, more durable set of paths into heavy music, built on consistent performance rather than novelty.

Extreme Metal: Technique, Power and Misconceptions

Women in Death, Black and Extreme Metal

Extreme metal has long been treated as the final gatekeeper of heaviness. Death metal, black metal, and related subgenres are built on speed, endurance, and vocal techniques that push the human body to its limits. For a long time, this space was presented as fundamentally incompatible with female voices. Not because of evidence, but because of assumption.

The misconception rested on biology rather than technique. Harsh vocals were framed as a natural extension of male physicality, ignoring the reality that growls, screams, and distorted vocals are learned skills. When women entered extreme metal scenes, their presence was often met with skepticism. Audiences questioned authenticity. Critics questioned longevity. The burden of proof was immediate and relentless.

Many early female extreme metal vocalists came up through underground networks rather than mainstream channels. Small clubs, tape trading, and independent labels formed the backbone of these scenes. Visibility was limited, but creative control was often greater. Without heavy label oversight, women could develop their styles without being reshaped for accessibility. This autonomy came at the cost of recognition, but it allowed technique to speak louder than image.

Within death metal, vocal distortion relies on breath control, diaphragm strength, and precise engagement of false vocal folds. These mechanics are not gendered. Yet female performers were often treated as curiosities, framed as shocking exceptions rather than practitioners of a craft. The focus remained on spectacle instead of skill.

Black metal introduced additional barriers. Its culture emphasized extremity not only in sound, but in ideology and presentation. Female musicians entering these spaces faced layered resistance. Questions of legitimacy merged with broader issues of exclusion and gatekeeping. In some scenes, women were discouraged from participation altogether, not through formal rules, but through social pressure and dismissal.

Despite this, female vocalists persisted. They refined techniques through trial, training, and shared knowledge. Many emphasized vocal health early, aware that damage would be used to discredit their presence. Touring conditions were harsh. Performances demanded consistency across long sets with minimal recovery time. Failure was not tolerated.

The focus here hinges on the contrast between perception and reality. Extreme metal does not reject female voices. Its culture often does. When listeners move past expectation, the sound itself offers no resistance. A well-executed growl carries authority regardless of who produces it.

Over time, the presence of women in extreme metal forced a reassessment of what power sounds like. Aggression became less tied to physical myth and more closely associated with control and intent. Vocalists who mastered these techniques challenged one of heavy music’s most persistent assumptions.

This groundwork prepared the way for artists who would later gain international recognition. Their success did not soften extreme metal. It sharpened it, proving that intensity thrives on discipline rather than exclusion.

Key Figures in Extreme Vocal Performance

As extreme metal slowly moved out of the underground and into wider visibility, a small number of female vocalists became unavoidable reference points. Not because they softened the genre, but because they mastered it. Their work forced listeners, critics, and fellow musicians to confront a simple reality. Technique outweighs assumption.

One of the most influential figures in this shift was Angela Gossow. When she joined Arch Enemy in 2000, the band was already respected within melodic death metal circles. Gossow did not alter their sound to accommodate her presence. Instead, she delivered deep, controlled growls that matched the intensity of her predecessors. Albums such as Wages of Sin and Anthems of Rebellion placed her voice front and center, not as novelty, but as weapon. Live performances removed any remaining doubt. Her stage presence was disciplined and direct, rooted in consistency rather than theatrics. Gossow’s later transition into band management further challenged industry norms, positioning her not only as a performer, but as a decision-maker within extreme metal’s business structures.

Following her tenure, Alissa White-Gluz expanded the conversation rather than replacing it. Joining Arch Enemy in 2014, White-Gluz brought a wider vocal range that included both harsh growls and controlled clean passages. Her technical versatility was paired with visible advocacy for vocal health, ethical touring practices, and personal discipline. Albums like War Eternal and Will to Power showcased precision rather than brute force. White-Gluz’s public presence, including interviews and educational content, helped demystify extreme vocal technique. She reframed it as trained skill rather than instinct, further undermining gendered myths around aggression.

A different but equally significant impact came from Tatiana Shmayluk, whose work with Jinjer blurred boundaries between groove metal, progressive structures, and extreme vocals. Shmayluk’s performances are defined by abrupt shifts. Clean, jazz-influenced phrasing can turn into deep growls within seconds, without loss of control. Tracks like “Pisces” became widely shared not because of shock value alone, but because of clarity. The contrast exposed how narrowly extreme vocals had been imagined. Shmayluk did not present aggression as constant. She treated it as one color among many, deployed with intention.

These artists did not emerge in isolation. They were supported by evolving scenes that slowly learned to evaluate performance rather than identity. Yet even at this stage, resistance persisted. Online discourse frequently framed female extreme vocalists as exceptions, emphasizing rarity over repetition. Praise often came packaged with surprise, reinforcing the very assumptions it claimed to overcome.

Touring remained a critical proving ground. Extreme metal tours are physically demanding, with minimal rest and high performance expectations. Consistency matters more than spectacle. Vocal fatigue, injury, or inconsistency quickly erodes credibility. Female vocalists operating in this space were acutely aware that failure would be interpreted as confirmation of bias rather than individual limitation. As a result, many adopted rigorous training and recovery routines early in their careers.

Another layer of pressure came from fan culture. While many listeners embraced female extreme vocalists enthusiastically, others approached with skepticism or outright hostility. Online forums and comment sections became arenas where legitimacy was debated, often detached from actual musical evaluation. The same performance that earned praise on stage could be questioned online, reinforcing the divide between lived experience and mediated perception.

Repetition ultimately shifted the balance. As more women demonstrated technical mastery over time, the narrative lost coherence. It became harder to argue that extreme metal was incompatible with female voices when albums, tours, and festival appearances consistently contradicted that claim. The sound spoke for itself.

By the late 2010s, female extreme vocalists were no longer treated solely as anomalies. They became points of reference for technique, endurance, and innovation. Vocal coaches cited their methods. Younger musicians studied their performances. The genre did not change its standards. It expanded its understanding of who could meet them.

Extreme metal remains demanding, unforgiving, and resistant to trends. That is precisely why the presence of women within it carries weight. Not because they are different, but because they prove that discipline, not exclusion, defines the limits of heavy music.

Vocal Technique, Training and Physical Reality

Behind every convincing heavy vocal performance sits a physical reality that rarely makes headlines. Power in rock and metal vocals is not a matter of instinct or toughness. It is built through technique, repetition, and an ongoing negotiation with the limits of the human body. For female vocalists, this reality has often been misunderstood or ignored, especially in genres that equate aggression with effortlessness.

Clean singing, distortion, growls, screams, and hybrid techniques rely on different muscular engagements. Diaphragmatic breath support, resonance placement, and controlled airflow are foundational across styles. The difference lies in how distortion is produced. Contrary to persistent myths, harsh vocals do not come from “destroying” the voice. They depend on precise engagement of structures such as the false vocal folds, combined with relaxed throat positioning and consistent breath pressure. When done correctly, the vocal cords themselves are protected rather than abused.

Many female vocalists entered heavy music without access to formal instruction. Early scenes did not offer structured vocal education, and much knowledge circulated informally through trial and error. This made injury common. Hoarseness, nodules, and chronic fatigue were treated as inevitable side effects of touring rather than warning signs. Women faced additional pressure. Any sign of strain was often framed as proof that their voices were unsuited for heavy music, rather than as a technical issue shared by performers of all genders.

Over time, professional training became more visible. Vocal coaches specializing in extreme styles began to systematize techniques that had previously been passed down informally. One of the most widely recognized figures in this field is Melissa Cross, whose work with touring musicians helped normalize the idea that screaming and growling require disciplined preparation. Her emphasis on warm-ups, cooldowns, hydration, and recovery reframed harsh vocals as athletic performance rather than reckless expression. Importantly, her approach applied equally to male and female singers, undermining biological arguments against women in extreme metal.

Classical training has also played a role, particularly among singers in symphonic and progressive metal. Operatic techniques emphasize breath control, posture, and resonance, all of which translate effectively to loud, amplified environments. Artists such as Tarja Turunen and Simone Simons demonstrated how disciplined technique could sustain long tours without sacrificing vocal health. Their success reinforced the idea that longevity is not tied to vocal style, but to method.

The touring environment presents its own challenges. Nightly performances, inconsistent acoustics, dry air, poor sleep, and travel fatigue place constant strain on the voice. Female vocalists often face additional stressors, including hormonal fluctuations that can affect vocal consistency. These factors are rarely discussed publicly, yet they shape performance decisions in subtle ways. Some singers adjust setlists or vocal arrangements during tours to protect their voices. Others rotate techniques, balancing harsh and clean passages to manage fatigue.

The physical demands of heavy vocals also intersect with expectations around appearance and energy. Audiences expect intensity, movement, and emotional commitment. Standing still to preserve breath support can be misread as disengagement. Pushing too hard to meet visual expectations can lead to injury. Many experienced vocalists learn to prioritize sound over spectacle, even when it contradicts traditional stage dynamics.

Female singers have often been more open about these realities, not as confessions, but as practical discussions. Lzzy Hale has spoken publicly about vocal health, rest, and the importance of pacing across tours. Alissa White-Gluz has emphasized disciplined training, physical fitness, and mental preparation as core components of extreme performance. These conversations challenge the romantic notion of suffering as proof of authenticity.

Another misconception involves vocal range and power. Lower registers are often associated with heaviness, leading to assumptions that female voices must compensate through distortion or volume. In reality, heaviness is shaped by phrasing, rhythm, and intent as much as pitch. A controlled mid-range scream can carry more weight than a forced low growl. Technique allows singers to work with their natural range rather than against it.

Injury remains a risk, even with training. Nodes, polyps, and inflammation can develop under strain, particularly during long touring cycles. Recovery requires rest, silence, and often medical intervention. For female vocalists, taking time off can carry professional consequences. Absence risks loss of momentum in an industry that still values constant visibility. This pressure has led some artists to perform through injury, worsening long-term damage. Others have chosen sustainability over speed, accepting slower career growth in exchange for vocal longevity.

These realities reveal heavy vocals as skilled labor. The voice is not an abstract symbol of emotion. It is a physical instrument shaped by anatomy, training, and environment. Female vocalists in rock and metal have had to learn this early, often under scrutiny. Their survival in the genre depends less on natural advantage and more on informed discipline.

Understanding vocal technique reframes the broader conversation. It shifts focus away from gendered assumptions and toward shared professional challenges. The question is no longer who belongs in heavy music, but who is willing to do the work required to sustain it. In that sense, the voice becomes a site of equality. It responds to care, preparation, and respect, regardless of who carries it.

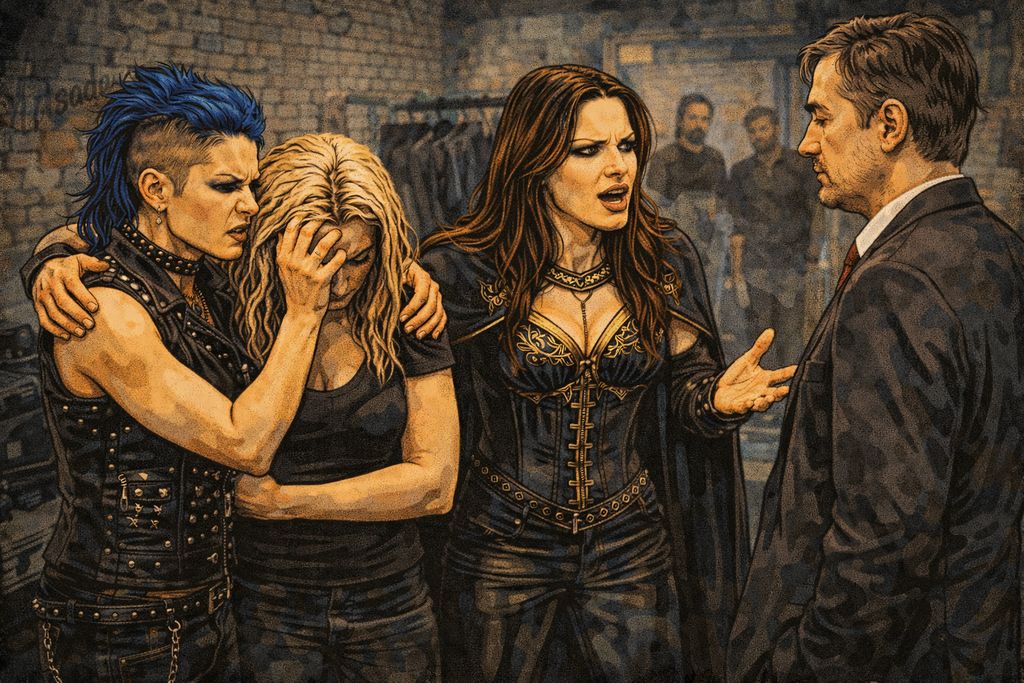

Frontwomen, Bands and Power Structures

Being the voice at the front of a band does not automatically mean holding power within it. For many female vocalists in rock and metal, visibility has often been mistaken for control. In reality, creative authority, financial decisions, and long-term direction are shaped by complex structures that do not always favor the person holding the microphone.

Historically, bands were organized around instrumental hierarchies. Guitarists and producers were often positioned as primary creators, while vocalists, especially women, were framed as interpreters rather than authors. This distinction mattered. Songwriting credits determined income. Production decisions shaped sound. Management contracts defined who spoke for the band. Female frontwomen frequently entered these structures after they were already in place, inheriting systems not designed with them in mind.

This imbalance affected perception as much as practice. When a band achieved success, male members were often credited with musical vision, while female vocalists were associated with image or emotion. Interviews reinforced this divide. Questions about songwriting processes were directed elsewhere. Questions about personal life, appearance, or stage presence landed with the singer. Over time, this framing influenced how authority was understood, even within bands that publicly presented themselves as egalitarian.

Several artists openly confronted this dynamic. Amy Lee has spoken extensively about early struggles to assert her role as Evanescence’s primary songwriter. Legal disputes in the mid-2000s revealed how easily creative contributions could be minimized when contracts lacked clarity. The public nature of these conflicts exposed a wider pattern rather than an isolated case. Visibility did not protect against marginalization.

In contrast, some female vocalists entered bands as founding members, shaping power structures from the outset. Sharon den Adel co-founded Within Temptation and maintained long-term involvement in songwriting and conceptual direction. This early positioning allowed for a more balanced internal dynamic. Authority grew alongside the band, rather than being negotiated retroactively. The difference lay not in personality, but in timing and structure.

The issue becomes more complex when bands rely on contrast-based vocal arrangements. In groups where female clean vocals are paired with male harsh vocals, assumptions about hierarchy can emerge subtly. The harsh voice is framed as aggression, the clean voice as melody. When those roles align with gender, power imbalances can follow. Cristina Scabbia has navigated this terrain by emphasizing collaboration and shared authorship, resisting narratives that reduce her role to sonic decoration.

Management and label relationships further complicate matters. Female frontwomen often become the public face of a band, responsible for promotion, interviews, and fan engagement. This labor is rarely reflected in contracts or compensation. At the same time, decision-making authority may remain elsewhere. The result is a mismatch between responsibility and control. When conflicts arise, the person most visible is often the most exposed.

Band breakups and lineup changes frequently reveal these dynamics. Departures are framed as personal issues rather than structural ones. When female vocalists leave bands, media narratives often focus on temperament or conflict, while similar exits by male members are discussed in terms of creative differences. This double standard reinforces the idea that women destabilize bands rather than respond to imbalance.

Touring intensifies these pressures. Frontwomen are expected to maintain performance quality while absorbing emotional labor, mediating conflicts, and representing the band publicly. Burnout is common. Yet stepping back can be interpreted as weakness or lack of commitment. The expectation to be both artist and anchor places disproportionate strain on female vocalists, particularly in long-running projects.

Some artists respond by reclaiming control outside traditional band structures. Solo projects, side collaborations, and independent releases offer avenues for experimentation and autonomy. Others move into production, songwriting for others, or management roles, expanding their influence beyond the stage. These paths challenge the assumption that power in heavy music must be centralized around traditional band hierarchies.

These patterns point to a spectrum of negotiation rather than a single narrative of exploitation. Power in bands is shaped by contracts, timing, personality, and industry context. Female vocalists have learned to navigate these variables with increasing awareness. Transparency around authorship, early involvement in decision-making, and clear contractual boundaries have become tools of survival rather than privileges.

Understanding frontwomen within power structures shifts the conversation away from charisma and toward labor. Being the voice of a band is work. It carries responsibility, risk, and visibility. When authority aligns with that visibility, bands tend to endure. When it does not, conflict follows.

Taken together, this explains why some careers stabilize while others fracture. Talent alone is not enough. Control over one’s work, voice, and narrative determines whether visibility becomes opportunity or liability in the long run.

Media Narratives, Sexism and Double Standards

Rock and metal journalism has long presented itself as oppositional, critical, and resistant to mainstream norms. Yet when it comes to gender, the media surrounding heavy music has often reproduced the same biases it claimed to reject. For female vocalists, coverage has rarely been neutral. It has shaped careers as much through framing as through exposure.

One of the most persistent patterns is the use of gender as a primary descriptor. Male vocalists are introduced by sound, band, or style. Female vocalists are frequently introduced by contrast. Phrases like “female-fronted metal” or “woman-led rock band” appear repeatedly, even when gender has no bearing on the music itself. These labels do more than describe. They signal difference and, implicitly, deviation from a presumed norm. Over time, they train audiences to hear women as categories rather than as musicians.

Interviews reveal the imbalance even more clearly. Female vocalists are often asked to explain their presence in heavy music, as if justification were required. Questions about confidence, intimidation, or acceptance recur with striking regularity. Male counterparts are rarely asked how it feels to sing in a male-dominated genre. The assumption of belonging runs in one direction only. This framing places women in a defensive position before a single note is discussed.

Reviews amplify these dynamics. Critical language used to describe female performances often centers on emotion and appearance. Voices are described as “haunting,” “ethereal,” or “beautiful,” even when the performance is aggressive, precise, or confrontational. Male vocalists performing similar material are described in terms of power, control, or intensity. The vocabulary itself reinforces stereotypes, shaping how performances are remembered.

Coverage around artists such as Tarja Turunen, Sharon den Adel, and Amy Lee has often leaned on those shorthand labels, even when the work is technical and forceful. The language makes the music easier to market, but it narrows how those voices are discussed.

The issue is not praise versus criticism. Many female vocalists receive positive coverage. The problem lies in the criteria applied. When success is framed as surprising, it implies that failure was expected. When longevity is treated as remarkable, it suggests that disappearance was the norm. These narratives accumulate quietly, affecting how careers are evaluated over time.

Media treatment during moments of conflict reveals deeper biases. Band breakups, lineup changes, or contractual disputes involving female vocalists are often personalized. Temperament, ego, or emotional instability become convenient explanations. Structural issues, such as ownership, creative control, or financial arrangements, receive less attention. Comparable conflicts involving male musicians are more likely to be framed as artistic disagreements or business decisions. The same event is interpreted differently depending on who is at the center of it.

The rise of online media and social platforms has both challenged and intensified these patterns. On one hand, female vocalists can now speak directly to audiences, bypassing traditional gatekeepers. Interviews, statements, and behind-the-scenes insights can be shared without editorial framing. This has allowed artists like Lzzy Hale and Alissa White-Gluz to address misconceptions openly, discuss technique, and set their own narratives.

Other artists have used the same channels to define their image and intent on their own terms, including Maria Brink and Floor Jansen. Direct access does not remove bias, but it shortens the distance between the artist and the audience.

On the other hand, online discourse has expanded the space for scrutiny. Comment sections, forums, and social media threads often reproduce the same double standards in more explicit form. Appearance, age, and perceived authenticity are debated alongside music, sometimes eclipsing it entirely. The immediacy of digital feedback amplifies judgment and shortens the distance between performance and reaction.

Another recurring issue is the framing of success as trend-driven. When multiple female-fronted bands gain attention in a short period, media narratives often describe a “wave” or “moment,” implying impermanence. This language suggests that visibility is cyclical rather than earned, and that decline is inevitable once novelty fades. Male-dominated scenes rarely receive similar treatment, even when stylistic trends clearly drive exposure.

Despite these patterns, change has been gradual but real. Long-running careers have made it harder to sustain dismissive narratives. When female vocalists headline festivals, release multiple acclaimed albums, and maintain consistent live performance standards over decades, the language of exception weakens. Repetition challenges stereotype more effectively than argument.

Some publications have begun reassessing their own practices, shifting toward more precise and less gendered criticism. Technical discussion of vocals, songwriting, and production appears more frequently, reducing reliance on visual or emotional shorthand. This progress is uneven, but noticeable.

Understanding media narratives is essential because they do not simply reflect reality. They shape it. Coverage influences booking decisions, label confidence, and audience expectations. For female vocalists, learning to navigate media framing has become an additional professional skill, alongside singing, touring, and writing.

A central tension becomes clear here. Heavy music often prides itself on authenticity and resistance, yet its media structures have been slow to confront their own biases. Progress has come not through declarations, but through sustained presence. Female vocalists have not waited for better coverage. They have outlasted it.

Scandals, Abuse and Industry Silence

Scandals in rock and metal are often discussed as isolated incidents. A bad tour. A toxic manager. A band that fell apart. For female vocalists, these moments rarely exist in isolation. They sit within an industry culture that has long normalized silence, imbalance, and endurance as professional virtues. Speaking up has carried consequences. Staying quiet has carried costs.

Here, individual names are avoided because the point is structural. The patterns matter more than the headlines.

Abuse in the heavy music ecosystem takes many forms. Some are overt. Sexual harassment by industry figures, coercive relationships, or unsafe touring environments. Others are structural. Contracts that strip artists of control. Management arrangements that blur professional boundaries. Label expectations that reward compliance over wellbeing. For women, these dynamics intersect with visibility in ways that intensify risk. Being the front-facing voice of a band makes exposure unavoidable, while protection remains inconsistent.

Touring has historically been one of the most vulnerable contexts. Long stretches on the road create enclosed environments where power imbalances are magnified. Crew members, promoters, and managers often hold logistical authority over schedules, accommodations, and access. Complaints can be reframed as inconvenience. Resistance can be labeled unprofessional. Many female vocalists have described learning to manage risk quietly, altering routines, avoiding spaces, or relying on informal networks for safety. These strategies were rarely acknowledged as labor, yet they demanded constant attention.

The music industry’s reliance on reputation has reinforced silence. Careers depend on relationships. A single complaint can jeopardize future bookings or label support, especially for artists without long track records. For emerging female vocalists, the calculation is stark. Speak and risk being excluded. Stay silent and absorb the damage. This dynamic has not been unique to heavy music, but the touring intensity and close-knit nature of metal scenes have amplified it.

Public scandals have occasionally forced attention onto these issues. When allegations surface, media coverage often focuses on shock rather than structure. Individuals are scrutinized. Patterns are sidelined. Female vocalists who come forward are asked to provide proof, context, and emotional restraint, all while navigating public exposure. The burden of credibility falls unevenly. Silence is questioned. Speaking is questioned more.

The emergence of the #MeToo movement shifted this landscape, including within rock and metal communities. Stories that had circulated privately gained public visibility. The language of consent, power, and accountability entered spaces that had previously framed misconduct as excess or misbehavior. For some female vocalists, this created an opening to articulate experiences that had long been minimized.

Yet the impact was uneven. While certain high-profile cases led to consequences, many others stalled in ambiguity. Bands disbanded quietly. Accusations were met with legal threats. Settlements were reached without transparency. In scenes that prize loyalty and subcultural identity, whistleblowers were sometimes framed as traitors rather than participants seeking accountability. The expectation to protect the scene often outweighed the imperative to protect individuals.

Industry silence has also operated through selective memory. Artists who leave bands under difficult circumstances are frequently written out of narratives. Their contributions are minimized. Their departures are explained through vague references to “differences” or “personal reasons.” Over time, the absence becomes normalized. This erasure compounds harm by stripping individuals of professional recognition alongside personal safety.

Female vocalists have responded in varied ways. Some have chosen to speak publicly, reframing their experiences as cautionary rather than confessional. Others have redirected their careers, moving toward independent releases, teaching, production, or management roles where control is greater. A number have stepped away from music entirely, citing exhaustion rather than scandal. The industry often treats these exits as personal choices, ignoring the conditions that made them necessary.

It is important to avoid sensationalism here. Not every career difficulty stems from abuse. Not every conflict reflects systemic failure. Heavy music is demanding by nature. Touring strains relationships. Creative differences are real. The problem arises when patterns repeat without accountability, and when silence becomes a prerequisite for survival.

Audience response has played a complex role. Fans often express support in principle, but discomfort in practice. Separating art from artist becomes a defensive reflex. This stance protects listening habits but can marginalize those who speak out. Female vocalists who challenge industry norms may find their work overshadowed by controversy, even when they are not responsible for the conditions that produced it.

Recent years have seen incremental change. Some festivals and promoters have adopted clearer codes of conduct. Tour managers and labels increasingly acknowledge the need for safer working environments. Conversations about mental health, boundaries, and sustainability have entered mainstream discourse. These shifts matter, but they remain fragile. Progress depends on enforcement, not intention.

It grounds the broader discussion in consequence. Voices are shaped not only by artistry, but by the conditions under which they are allowed to exist. Abuse, silence, and scandal are not peripheral to the history of female rock and metal vocalists. They are part of the terrain.

Understanding this does not diminish the music. It clarifies what it has cost. Endurance should not be confused with consent. Survival should not be mistaken for approval. The fact that so many women have sustained careers in heavy music despite these conditions speaks not to the industry’s fairness, but to their resilience.

The next chapters look outward again, toward geography, audiences, and longevity. But the weight of this section carries forward. It reminds us that progress in heavy music has never been linear. It has been negotiated under pressure, often in silence, and sometimes at great personal expense.

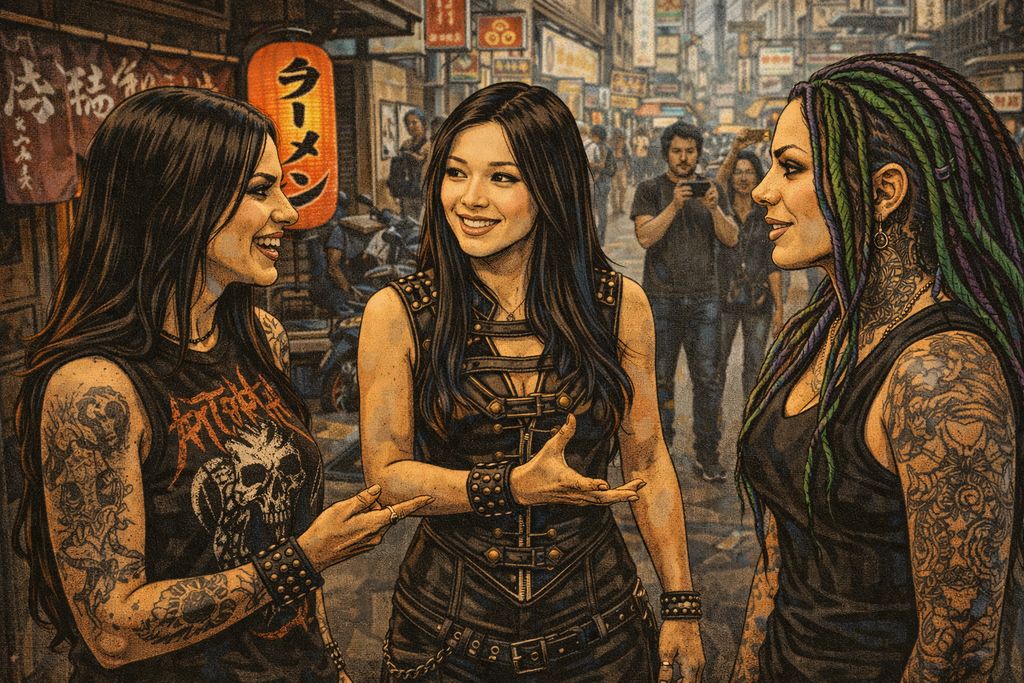

Global Perspectives: Beyond the US and UK

Discussions about rock and metal often default to the United States and the United Kingdom, treating them as cultural centers from which everything else radiates. For female vocalists, this narrow focus hides a much broader reality. Some of the most sustained, technically advanced, and culturally significant careers in heavy music have developed outside the Anglo-American spotlight.

In continental Europe, metal has long been supported by strong festival cultures, public broadcasting, and dedicated touring circuits. This infrastructure created conditions where female vocalists could build long-term careers without relying on short-lived trends. Germany, the Netherlands, Scandinavia, and parts of Eastern Europe became environments where heaviness was taken seriously as a craft rather than a novelty.

Germany offers a clear example through Doro Pesch, whose career extends far beyond her 1980s breakthrough. Doro’s continued presence on major festival stages well into later decades challenged assumptions about age, gender, and relevance. Her reception in Europe differed markedly from media treatment in the US, where female metal vocalists were more often framed as exceptions. In Germany, consistency mattered more than novelty. A strong live performance earned respect, regardless of who delivered it.

The Netherlands emerged as a key center for symphonic and gothic metal, offering multiple pathways for female-led bands. Artists such as Anneke van Giersbergen, Sharon den Adel, Simone Simons, and Floor Jansen became reference points for different shades of heaviness. Beyond well-known figures, the scene normalized women in leadership roles across songwriting, performance, and management. This normalization reduced the need for constant justification. Artists could focus on refining sound rather than defending presence. The result was a concentration of technically skilled vocalists operating within stable band structures.

Scandinavia presents a different case. Countries like Sweden and Finland developed metal scenes that valued precision, discipline, and endurance. Liv Kristine in Norway and Elize Ryd in Sweden illustrate how distinct vocal styles could thrive in these environments, from gothic traditions to modern metal hybrids. While still male-dominated, these scenes placed less emphasis on image and more on live credibility. Female vocalists entering these environments were judged harshly, but consistently. The standards were high, yet applied more evenly. This allowed some artists to build reputations through repetition rather than publicity.

Japan offers one of the most distinct global perspectives. Heavy metal there developed alongside a broader culture of musical virtuosity and genre experimentation. Female artists have played prominent roles across rock and metal since the 1980s, often with greater mainstream visibility than in Western markets. Mari Hamada stands as a central figure. Her powerful, controlled vocal style and extensive discography established her as a foundational voice in Japanese metal. Unlike many Western counterparts, Hamada’s career was not framed as transgressive. It was framed as professional. Su-metal later brought Babymetal to global attention, presenting a different model of heavy music that still carried technical discipline and stage precision.

In Japan, female-fronted metal bands often navigated fewer public debates about legitimacy. The industry’s focus on technical skill and performance consistency created space for women to lead without constant explanation. This did not eliminate gender bias, but it altered its expression. Authority was tied more closely to output than to image.

Latin America represents another vital but underrepresented region. Metal scenes in Brazil, Argentina, Chile, and Mexico developed under different social pressures, including political instability and limited industry infrastructure. Female vocalists in these contexts often faced compounded challenges. Gender bias intersected with economic constraints and limited access to international touring. Despite this, vibrant underground scenes flourished. Brazil has produced prominent extreme and thrash acts led by vocalists such as Fernanda Lira, first with Nervosa and later with Crypta. Local festivals, independent labels, and cross-border touring networks sustained careers that rarely received global coverage.

Eastern Europe and parts of Asia have followed similar patterns. Female vocalists often built influence regionally, supported by dedicated fan bases and live circuits. Ukraine’s Jinjer, led by Tatiana Shmayluk, is one of the clearer cases where a regional act broke into sustained global touring. International recognition, when it arrived, tended to be delayed rather than denied. By the time global audiences noticed, these artists were already seasoned performers.

These global perspectives align around alternative pathways rather than uniform opportunity. Outside the US and UK, success was often measured by durability rather than chart placement. Careers unfolded over decades rather than release cycles. Female vocalists benefited from scenes that valued commitment and live performance over constant reinvention.

Language also played a role. Singing in non-English languages sometimes limited international reach, but it strengthened local identity. Vocalists who chose to perform in their native languages often cultivated deeper connections with audiences. This choice challenged the assumption that English-language delivery was a prerequisite for heaviness or legitimacy.

Global metal festivals have increasingly brought these regional scenes into contact. Shared stages exposed audiences to different vocal traditions and performance styles. Over time, the presence of female vocalists from diverse backgrounds weakened the narrative that heavy music followed a single cultural template.

It also reframes the idea of progress. Change did not always move outward from a center. In many cases, it developed independently, shaped by local conditions and priorities. Female rock and metal vocalists have never belonged to one scene or one story. Their impact is global, even when recognition has lagged behind reality.

Audiences, Gatekeeping and Female Fans

Heavy music has always defined itself through community. Scenes are built in clubs, at festivals, in record stores, and online spaces where taste, knowledge, and loyalty carry social weight. For female vocalists, audiences have been both a source of strength and a site of resistance. Acceptance has rarely been automatic. It has been negotiated in real time, often under scrutiny.

Gatekeeping plays a central role in this process. In rock and metal, credibility is frequently measured through familiarity with genre history, technical detail, and subcultural codes. These standards are presented as neutral, but they are often enforced unevenly. Female artists and fans alike are more likely to be tested, questioned, or challenged to prove legitimacy. Knowing the music is not always enough. Authority must be demonstrated repeatedly.

Live shows reveal these dynamics clearly. In many scenes, female-fronted bands initially face skepticism from portions of the crowd. Arms crossed. Limited movement. Watchful distance. The test is unspoken but familiar. Can this band deliver? For experienced performers, this moment becomes routine. A convincing set often dissolves resistance quickly. Sound carries more weight than expectation. Yet the fact that the test exists at all reflects deeper assumptions about who belongs on heavy stages.

For well-known acts, familiarity shifts the room. Audiences coming to see Nightwish, Evanescence, Halestorm, or Within Temptation tend to judge by performance first, not by who is fronting the band. That change matters, because it turns visibility into normalcy rather than novelty.

Female fans occupy a similarly complicated position. Women have always been present in rock and metal audiences, but their presence has often been framed as peripheral. They are assumed to be partners rather than participants, observers rather than experts. This assumption shapes behavior at shows, in record shops, and online. Questioning, dismissal, or condescension becomes part of the experience. Many women respond by withdrawing into smaller, more supportive communities. Others confront gatekeeping directly, insisting on visibility.

The rise of social media and online platforms has altered this landscape. Digital spaces allow fans and artists to connect without traditional intermediaries. Female vocalists can build audiences directly, sharing rehearsal footage, vocal breakdowns, and tour life without editorial framing. This transparency has helped shift perception. Seeing the work behind the performance challenges stereotypes about ease or novelty.

At the same time, online spaces can intensify scrutiny. Comment sections often become arenas for debate over authenticity, appearance, or genre purity. Praise is frequently accompanied by surprise. Criticism can slide into personal attack. For female vocalists, managing audience engagement becomes another layer of labor. Decisions about when to respond, when to ignore, and when to withdraw shape mental health as much as career trajectory.

Festivals offer a broader perspective. As female-fronted bands appear more frequently on large stages, audience behavior changes. Visibility at scale normalizes presence. Seeing multiple women perform across a lineup weakens the narrative of exception. Younger fans, in particular, respond differently. For many, gender is no longer a defining feature of heaviness. Sound and performance take precedence.

Female fans have also played a crucial role in sustaining scenes. Fan clubs, grassroots promotion, and local support networks often rely heavily on women’s unpaid labor. Organizing travel, sharing information, and building online communities create infrastructure that benefits entire scenes. This contribution is rarely acknowledged publicly, yet it shapes which bands endure.

There is a feedback loop at work. When female fans see women on stage, participation feels safer and more accessible. When participation grows, scenes diversify. Gatekeeping loses some of its power. This process is uneven and incomplete, but visible. The presence of female vocalists does not automatically transform audiences, but it creates reference points that shift expectation over time.

Resistance remains. Some fans continue to frame inclusion as dilution, diversity as threat. These arguments often rely on nostalgia rather than evidence. Heavy music has always evolved. New sounds and voices have repeatedly been met with skepticism before becoming accepted. Female participation follows the same pattern, slowed by bias but sustained by persistence.

Understanding audience dynamics is essential because music does not exist in isolation. Scenes are co-created by performers and listeners. Acceptance is not granted once and for all. It is rehearsed at every show, in every discussion, and across every platform. Female rock and metal vocalists have learned to navigate these spaces with awareness and resilience.

Their presence has changed who feels welcome in heavy music. Not completely. Not evenly. But enough to matter. The final chapter looks at what happens when careers extend beyond breakthrough moments, and how aging, time, and endurance reshape expectations in a genre obsessed with intensity.

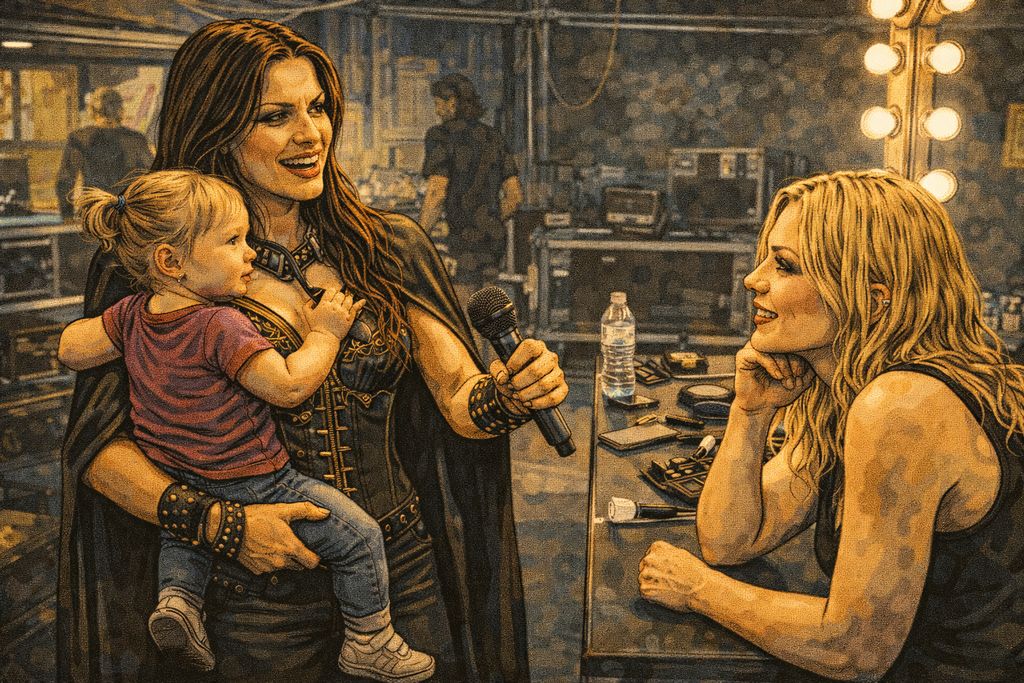

Aging, Motherhood and Career Longevity

Rock and metal have long celebrated intensity, speed, and physical endurance. Youth has often been treated as an unspoken prerequisite, while aging is framed as decline rather than adaptation. For female vocalists, this pressure is magnified. Expectations around appearance, energy, and availability intersect with biological and social realities in ways that are rarely addressed openly.

Aging in heavy music is not simply about losing range or stamina. It is about managing time, recovery, and shifting priorities in an industry that still rewards constant output. Long tours, late nights, and physical strain accumulate over decades. Male artists are often granted cultural permission to age visibly. Wrinkles, gray hair, and slowed movement are reframed as experience. Female artists face a narrower window of acceptance. Aging can be treated as incompatibility rather than evolution.