What Makes a Soul Legend?

Soul music was never about perfection. It was about truth. About voices that carried lived experience rather than polish, and about singers who sounded like they meant every word they sang. When we speak of female soul legends, we are not talking about chart success alone, or vocal technique in isolation. We are talking about women who carried emotional authority into every room they entered.

Soul emerged from gospel, blues, and rhythm and blues, shaped by church discipline, community memory, and social pressure. For women, this music became both a platform and a burden. Their voices were celebrated, yet their autonomy was often restricted. Their pain was admired, but rarely protected.

What defines a soul legend is not just a famous song or a timeless album. It is the ability to translate private emotion into collective experience. Artists like Aretha Franklin, Nina Simone, or Etta James did not simply perform songs. They embodied them.

This article explores how female soul artists shaped the genre, navigated power structures, endured exploitation, and left legacies that still define what emotional honesty in music can sound like.

Gospel Roots and the Birth of Female Soul (1940s–1950s)

The Black Church as Vocal Training Ground

Long before soul music reached recording studios, it was shaped in church pews, choir rehearsals, and Sunday services. For many female soul singers, the Black church was not only a spiritual space but also their first school of music. It taught discipline, projection, timing, and most importantly, emotional commitment. Singing was not a performance meant to impress. It was an act of testimony.

Church music demanded presence. A singer had to fill the room without amplification, respond to the congregation, and sustain long passages without rest. This environment produced voices that were strong, flexible, and deeply expressive. Call and response was not a technique learned later in studios. It was lived experience, repeated week after week.

For women, the church offered something the outside world often denied them: authority. A strong female voice could lead a congregation, set the emotional tone of a service, and command attention without apology. Yet this authority came with limits. Leadership was accepted in song, but rarely extended beyond it.

Artists such as Mahalia Jackson embodied this tradition. Her voice carried weight because it was rooted in conviction, not ornamentation. She did not sing to entertain. She sang to affirm belief, grief, and hope. That emotional clarity later became a blueprint for soul expression.

Others, like Sister Rosetta Tharpe, pushed these boundaries further. By blending gospel phrasing with blues structures and electric guitar, she challenged the idea that sacred music had to remain sonically contained. Her performances unsettled audiences, but they also expanded what vocal authority could sound like.

This church-based training created singers who understood emotion as something communal. That understanding would later define soul music itself.

The church did not only shape voices. It shaped behavior, endurance, and a clear sense of hierarchy. Choirs were structured environments. Singers learned when to step forward and when to step back, how to listen as closely as they projected, and how to serve a collective sound without losing individual presence. This balance would later become crucial for women navigating the professional soul industry.

For young female singers, discipline was not optional. Rehearsals were strict, often unpaid, and emotionally demanding. Mistakes were corrected publicly. Endurance was tested through long services, extended songs, and repeated performances. This environment produced singers who could sustain emotional intensity without collapse. It also normalized the idea that emotional labor was expected and rarely questioned.

Within choirs, authority was earned through consistency rather than charisma. Solo parts were given to those who could be trusted to carry the room without losing control. This early form of musical leadership trained women to command attention without excess. It was a quiet authority, rooted in reliability and emotional clarity.

This background helps explain why many female soul singers later appeared unshaken in front of microphones and orchestras. Their confidence did not come from the studio. It came from years of standing in front of congregations that demanded honesty above all else.

Artists like Aretha Franklin grew up in this environment. As the daughter of a prominent preacher, she witnessed firsthand how voice, faith, and leadership intertwined. Her early recordings already reflected a sense of control that went beyond technical skill. She knew how to lead listeners without forcing them.

The church also taught restraint. Not every emotion needed to be displayed at full volume. Knowing when to hold back became just as important as knowing when to release. This understanding would later define the emotional pacing of classic soul recordings.

What truly distinguished church-trained singers was not volume or range, but their relationship with the people in front of them. Emotion was never delivered into silence. It was shaped by reaction. A held breath, a shouted affirmation, a sudden hush. These responses guided the singer in real time. Expression was adjusted, extended, or restrained depending on the room.

This constant exchange taught female singers to read emotional space with precision. They learned that a voice could comfort, challenge, or steady a crowd. Singing became less about self expression and more about shared experience. The goal was not to impress, but to connect. That instinct would later separate soul singers from technically flawless but emotionally distant performers.

Communal response also encouraged vulnerability. In church, emotion was not hidden. Tears, joy, exhaustion, and spiritual release were visible and accepted. Female singers grew comfortable allowing their voices to crack, stretch, or darken when emotion demanded it. This acceptance of imperfection would become one of soul music’s defining qualities.

Artists like Gladys Knight carried this sensitivity into their later careers. Her phrasing often felt conversational, shaped by pauses and subtle shifts rather than force. That approach reflected a deep understanding of how listeners receive emotion, not just how singers project it.

This training also created a sense of responsibility. When a singer stepped forward, she carried the emotional weight of others. That awareness fostered control. Even at moments of intensity, the voice remained anchored. The singer stayed present, aware that the song belonged to everyone in the room.

Soul music would later amplify this dynamic through microphones, records, and radio. But its foundation remained communal. Female soul legends did not simply sing emotions. They shared them, shaped them, and gave them space to exist collectively.

From Sacred to Secular – Crossing Moral and Cultural Lines

For many female singers, the move from church to secular music was not a smooth transition. It was a rupture. Gospel singing carried moral weight, community trust, and spiritual responsibility. Stepping outside that space often meant facing disappointment, judgment, or outright rejection. The decision to sing outside the church was rarely framed as artistic growth. It was framed as betrayal.

Yet economic reality played a decisive role. Gospel rarely provided financial stability, especially for women. Recording contracts, radio exposure, and touring opportunities existed almost exclusively in the secular world. For singers with families to support or limited options, the choice was not between faith and fame. It was between survival and silence.

This crossing required adjustment. Secular audiences listened differently. Where church congregations responded openly, clubs and theaters expected entertainment. Emotion had to be shaped for listeners who did not share the same spiritual language. Female singers learned to translate conviction into phrasing, intensity into tone, and belief into storytelling.

Ruth Brown represents this transition clearly. Her early recordings carried gospel-inflected power, but they were framed within rhythm and blues structures designed for radio and dance halls. While her voice drove Atlantic Records’ commercial success, her personal control over contracts and royalties remained limited. The shift brought visibility, but also vulnerability.

For others, the boundary between sacred and secular never fully disappeared. Mahalia Jackson famously resisted secular recording, yet collaborated with soul and rhythm and blues musicians in live contexts. Her presence influenced the genre without abandoning her roots. This tension illustrates how fluid the boundary truly was.

The first crossings were rarely clean breaks. They were negotiated spaces, marked by compromise, internal conflict, and gradual adaptation. These early decisions shaped not only careers, but the emotional language of soul itself.

Leaving the church did not mean leaving its values behind. For many female singers, the moral framework of their upbringing remained present long after their music entered secular spaces. This created internal conflict. Singing about love, desire, or heartbreak for a paying audience could feel exposed, even improper, when measured against church expectations. These tensions were rarely resolved quickly. They followed artists throughout their careers.

Community pressure intensified this struggle. In tightly knit church environments, reputation mattered. A woman’s voice could be celebrated on Sunday and questioned by Monday. Gossip traveled fast, and success outside the church was not always welcomed. Female singers were judged not only for their music, but for their appearance, their independence, and their willingness to step beyond prescribed roles.

Public judgment added another layer. Once a singer entered the secular market, her image became subject to scrutiny from audiences who knew nothing of her background. Critics and listeners often interpreted emotional intensity as excess, or vulnerability as weakness. The depth that made soul music powerful was sometimes framed as instability.

This double bind placed women in a difficult position. To soften their expression risked losing authenticity. To remain emotionally open invited misinterpretation. Many learned to navigate this by developing controlled personas, carefully balancing warmth and distance. This skill would later be mistaken for natural charisma, when it was in fact a form of self protection.

The moral tension between sacred roots and secular exposure also influenced lyrical choices. Songs often carried traces of confession, restraint, or longing for reassurance. Even in love songs, echoes of spiritual language remained. This blend gave soul music its unique gravity.

These early experiences shaped how female soul artists understood visibility. Being seen was necessary, but it was never entirely safe. The awareness of being judged became part of the emotional weight they carried into every performance.

Adapting to secular audiences required more than a change in repertoire. It demanded a recalibration of how emotion was delivered. In church, intensity was welcomed and even encouraged. In clubs, theaters, and studios, it had to be shaped differently. Too much fervor could feel overwhelming. Too much restraint could feel distant. Female singers learned to adjust their voices without losing their core identity.

This adaptation often began with phrasing. Gospel-trained singers were used to extended lines, spontaneous improvisation, and emotional peaks guided by communal response. Secular formats were tighter. Songs had fixed lengths, clear structures, and commercial expectations. Emotion had to be condensed. Every phrase needed intention. Silence became as important as sound.

Studio environments intensified this shift. Microphones captured details that large rooms never could. Breaths, cracks, and subtle shifts in tone became audible. For many women, this was both a challenge and an opportunity. The voice no longer had to overpower a space. It could invite listeners in. This intimacy became a defining feature of soul recordings.

Artists like Dionne Warwick exemplified this controlled adaptation. Her delivery was precise, measured, and emotionally contained, yet deeply expressive. While her style differed from gospel-driven powerhouses, it reflected the same understanding of emotional communication, refined for a different audience.

Adapting did not mean abandoning roots. The strongest female soul singers carried their church training beneath the surface. Even in restrained performances, the sense of conviction remained. Listeners could feel that the emotion was grounded, not performed for effect.

This balance between intimacy and intensity allowed soul music to reach wider audiences without losing its emotional core. Female singers became translators, carrying the language of communal expression into spaces that demanded subtlety and control.

Early Female Trailblazers Before the Soul Boom

Before soul became a clearly defined genre in the 1960s, a number of female singers were already shaping its emotional and musical foundations. They worked in spaces where gospel, blues, and rhythm and blues overlapped, often without the benefit of later recognition. Their careers unfolded in a period when categories were fluid, but opportunities for women were sharply limited.

These early trailblazers were rarely marketed as innovators. They were framed as performers rather than architects of sound. Yet their recordings reveal techniques and emotional approaches that would later be considered essential to soul music. Strong phrasing, controlled vibrato, and a willingness to let emotion lead rather than decorate were already present.

Ruth Brown stands as a key example. In the early 1950s, her recordings for Atlantic Records helped define the label’s identity. Songs like “Mama, He Treats Your Daughter Mean” carried emotional urgency without theatrical excess. Brown’s voice balanced strength and vulnerability, setting a model that many later soul singers would follow. Despite her commercial impact, she struggled for years to gain fair recognition and compensation, a pattern that would repeat across the genre.

Another important figure is LaVern Baker. Her performances combined humor, grit, and emotional clarity, challenging narrow expectations of how women could sound in popular music. Baker’s work demonstrated that authority did not require solemnity. It could coexist with playfulness and resilience.

These women operated in an industry that had not yet learned how to market female emotional depth without exploitation. Their careers were shaped by constant touring, limited creative control, and racial barriers that restricted long term stability. Yet their influence was lasting. They provided the emotional vocabulary that later soul legends would expand and refine.

By the time the soul boom arrived, much of its expressive language was already in place. It had been carried forward quietly by women whose contributions deserve recognition not as precursors, but as foundational voices.

The Golden Age of Female Soul (1960s)

Soul and the Civil Rights Movement

The rise of soul music in the 1960s cannot be separated from the civil rights movement. This was a period in which personal expression and political reality were deeply intertwined. For female soul singers, the microphone became more than a musical tool. It became a way to speak within a public conversation that often excluded them.

Many of these women did not present themselves as activists in the traditional sense. Their power lay elsewhere. It was carried through tone, phrasing, and emotional insistence. Singing about dignity, heartbreak, or self respect took on political meaning in a society built on inequality. The personal became public the moment it was heard.

Aretha Franklin embodied this shift. Songs like “Respect” were not written as protest anthems, yet they resonated far beyond their original context. Her delivery transformed familiar themes into statements of autonomy and demand. The authority in her voice reflected a broader insistence on being seen and heard, especially for Black women whose labor and voices had long been undervalued.

Others were more direct. Nina Simone used her platform to confront injustice openly. Her performances carried urgency and anger alongside vulnerability. She did not soften her message for comfort. In doing so, she challenged audiences to sit with discomfort rather than escape it. This approach came at a cost, affecting her commercial opportunities and public reception.

What united these artists was not a shared political strategy, but a shared emotional honesty. Soul music allowed them to articulate fear, hope, exhaustion, and resolve without reducing these feelings to slogans. Listeners recognized their own experiences in these voices, even when the lyrics remained personal rather than overtly political.

Female soul singers became emotional witnesses to their time. Their music did not document events directly, but it captured the atmosphere of urgency and change. In doing so, they gave the civil rights era a human sound, one shaped by resilience rather than rhetoric.

Female soul singers in the 1960s were expected to project strength without appearing defiant and vulnerability without appearing weak. This narrow space demanded constant negotiation. Dignity was not only a personal value, but a public performance shaped by audience expectation and industry pressure. Every gesture, every vocal inflection carried meaning beyond the song itself.

Many artists learned to communicate resilience through restraint. Rather than dramatic outbursts, they used controlled phrasing and deliberate pacing. This approach allowed listeners to feel depth without being overwhelmed. Strength was conveyed through steadiness, through the refusal to collapse emotionally even when the lyrics suggested pain.

Gladys Knight exemplified this balance. Her voice rarely forced emotion. Instead, it guided the listener gently, creating space for reflection. Songs like “Neither One of Us” conveyed heartbreak with composure, suggesting endurance rather than despair. This emotional discipline resonated strongly with audiences who recognized the effort required to maintain such control.

At the same time, vulnerability remained central to soul’s appeal. Singers allowed cracks in their voices, moments of hesitation, or softened endings to signal honesty. These details made performances feel lived in rather than polished. They invited listeners into emotional proximity.

Public reception was not always kind. Displays of vulnerability could be misread as instability, especially when expressed by women. Displays of strength could be framed as arrogance. Female soul singers navigated this tension with awareness, learning how to assert presence without inviting backlash.

Through this careful balance, they expanded the emotional language available to popular music. They demonstrated that dignity did not require emotional distance, and that vulnerability did not erase authority. This nuanced expression became one of soul music’s lasting contributions, influencing generations of singers across genres.

Live performances played a crucial role in how female soul singers were perceived during the civil rights era. Concerts were not just musical events. They were public gatherings where emotion, politics, and visibility intersected. Benefit shows, church concerts, and community events created spaces where music carried shared meaning beyond entertainment.

These appearances demanded a particular form of presence. Singers were expected to inspire without inciting, to uplift without provoking fear. For women, this balance was especially delicate. Their voices carried hope and defiance, but their bodies and expressions were closely watched. Every movement could be interpreted as a statement, intended or not.

Artists such as Aretha Franklin became central figures at benefit concerts and civic gatherings. Her performances were often received as affirmations of collective strength. She did not deliver speeches from the stage. Instead, her authority emerged through phrasing, timing, and emotional clarity. The audience understood the message without it being spoken.

Other singers chose quieter forms of engagement. Appearing at local events, churches, or community halls allowed them to remain connected to their roots. These performances reinforced trust. They reminded listeners that the voices they heard on records were grounded in shared experience, not distant celebrity.

Public appearances also carried risk. Association with political causes could limit radio play or touring opportunities. Some artists faced pressure from labels to remain neutral or ambiguous. Choosing when and where to appear became a strategic decision, shaped by personal conviction and professional survival.

Despite these constraints, female soul singers helped define the soundscape of the era’s public life. Their concerts provided moments of emotional release and collective reassurance. In spaces marked by tension and uncertainty, their voices offered steadiness. They did not claim leadership through slogans. They earned it through presence.

Vocal Authority, Emotional Truth and Studio Power

The recording studio changed the rules of soul music. Unlike live performances, where emotion could expand and adjust in response to a room, the studio demanded precision. Takes were limited, arrangements were fixed, and time was money. For female soul singers, this environment required a different kind of authority, one that combined emotional depth with discipline.

Studio sessions often placed women in vulnerable positions. Producers, engineers, and label representatives were usually male, and decisions about sound, tempo, and interpretation were rarely collaborative in the modern sense. Yet many female soul singers learned to assert control through their voices rather than through conversation. They shaped songs from the inside, adjusting phrasing, timing, and emphasis until the emotional center felt right.

Aretha Franklin is again a defining example. Her most influential recordings reveal a singer fully aware of how to use the microphone. She did not overpower it. She leaned into it. Small shifts in volume, subtle pauses, and carefully placed emphasis gave her performances authority without excess. The studio became an extension of her emotional language, not a limitation.

Emotional control did not mean emotional distance. In fact, the studio amplified intimacy. Listeners could hear breath, hesitation, and restraint. These details created closeness. They made songs feel confessional without becoming exposed. For female singers, mastering this balance was essential. Too much intensity could sound uncontrolled. Too little could sound detached.

Other artists approached the studio differently. Dionne Warwick worked within tightly structured arrangements that left little room for improvisation. Her authority came from clarity and precision. Each note felt intentional, each phrase measured. Though stylistically distinct, this approach reflected the same understanding of emotional responsibility.

The studio rewarded singers who knew exactly what they wanted to communicate. Female soul legends used this space to refine their voices, transforming raw feeling into recordings that felt both personal and composed. In doing so, they defined what emotional authority on record could sound like.

Behind every classic soul recording stood a network of producers, arrangers, and session musicians who shaped the final sound. For female singers, working within this structure required careful negotiation. Creative decisions were often framed as technical matters, even when they directly affected emotional delivery. Gaining influence meant understanding the language of the studio as well as the language of feeling.

Many producers viewed singers as interpreters rather than collaborators. Arrangements arrived largely finished. Tempos were set, keys chosen, backing vocals planned. Within these constraints, female soul singers learned to assert themselves subtly. A delayed entrance, a held note, or a rephrased line could shift the emotional center of a song without challenging authority openly.

Some artists built long term working relationships that allowed for greater trust. Aretha Franklin famously found creative freedom when surrounded by musicians who responded to her instincts rather than imposing rigid structures. In those sessions, her voice guided the band, not the other way around. The resulting recordings carried a sense of immediacy that felt alive rather than assembled.

Others operated within more controlled frameworks. Dionne Warwick worked with detailed arrangements that left little room for deviation. Her collaboration relied on precision and mutual understanding. Emotional nuance emerged through timing and articulation rather than spontaneous shifts. This approach required discipline and restraint, but it also produced clarity and consistency.

Session musicians played a critical role in these dynamics. Many were highly skilled and responsive, capable of adjusting in real time to a singer’s phrasing. When trust existed, the studio became a shared space of creation. When it did not, singers were expected to fit neatly into predefined roles.

Navigating these relationships demanded emotional intelligence. Female soul singers learned when to push and when to adapt, when to insist and when to wait. Their success was not only vocal. It was strategic. Through these collaborations, they shaped recordings that carried their identity even within restrictive systems.

Defining a recognizable personal sound was one of the greatest challenges for female soul singers working within rigid industry structures. Labels valued consistency. Radio demanded familiarity. Producers favored formulas that had already proven successful. Within these limits, individuality had to be carefully carved out rather than openly claimed.

For many artists, this process unfolded gradually. Early recordings often followed label expectations closely. Over time, subtle shifts appeared. A singer might insist on a different tempo, alter melodic phrasing, or introduce emotional pauses that set her apart. These changes were rarely dramatic, but they accumulated. Listeners began to recognize a voice not just by tone, but by emotional approach.

Etta James developed her sound through contrast. Her recordings moved between tenderness and raw intensity, often within the same song. Industry expectations could not fully contain this range. Rather than smoothing her edges, she leaned into them, allowing emotional volatility to become part of her identity. This carried risk, but it also made her unmistakable.

Others shaped their sound through consistency. Gladys Knight built recognition through clarity and emotional balance. Her phrasing remained steady, her tone grounded. Listeners trusted her voice because it felt reliable without becoming predictable. This trust translated into longevity.

Industry limits also affected repertoire. Singers were often assigned material rather than choosing it. Personal sound emerged through interpretation. A familiar lyric could feel new when filtered through lived experience. A standard arrangement could carry unexpected weight when delivered with conviction.

Defining a personal sound was therefore less about freedom than about persistence. Female soul singers learned to inhabit the spaces they were given fully. Within narrow boundaries, they expanded emotional range. Within fixed structures, they found room to breathe. The result was a body of work that felt deeply personal, even when created under constraint.

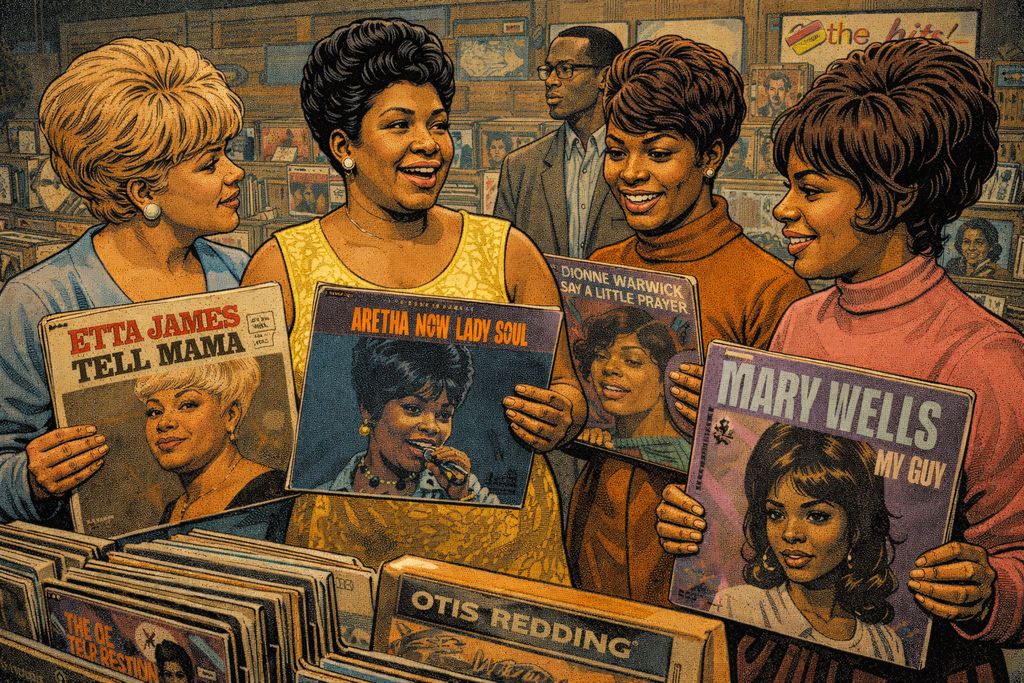

Albums and Songs That Defined the Era

The 1960s produced a body of work that continues to define what soul music means. For female artists, albums and songs were not just collections of performances. They were statements of presence. In an industry that often reduced women to voices for hire, these recordings asserted identity, emotion, and authority.

One of the most influential examples is I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You by Aretha Franklin. Recorded in 1967, the album captured a rare balance between raw feeling and structural clarity. Songs like “Respect” and “Do Right Woman, Do Right Man” resonated because they sounded lived in. Franklin’s voice did not decorate the material. It inhabited it. The album’s impact lay not only in its success, but in how it redefined expectations of female vocal authority in popular music.

Equally important, though very different in tone, were the recordings of Nina Simone. Albums such as Pastel Blues and Nina Simone in Concert blurred the line between performance and testimony. Songs like “I Put a Spell on You” and “Mississippi Goddam” confronted listeners directly. Simone’s work demonstrated that soul could carry anger, irony, and political clarity without sacrificing musical depth.

Other defining recordings came from artists who balanced emotional intensity with accessibility. Singles by Etta James, including “At Last,” offered vulnerability without fragility. Her phrasing carried longing and strength in equal measure, making the song a reference point for emotional sincerity.

What united these recordings was not style, but intention. Each album and song established a voice that felt unmistakably personal. These works did not aim to capture trends. They created standards. Decades later, they remain touchstones, not because they sound timeless, but because they sound truthful. That truth is what continues to define the era.

Commercial success in the 1960s did not arrive evenly for female soul artists, nor did it mean the same thing for each of them. Radio play, chart positions, and crossover appeal opened doors, but they also introduced new forms of limitation. Success increased visibility, yet it often narrowed expectations. Once a sound worked, labels pushed to repeat it.

Radio was the primary gatekeeper. Program directors favored voices that felt familiar and emotionally accessible. Songs had to fit time constraints and tonal norms. For female soul singers, this meant negotiating how much intensity could be broadcast without being labeled excessive. Those who succeeded learned to compress emotion without flattening it.

Dionne Warwick achieved wide radio success through songs that balanced emotional depth with structural clarity. Her recordings fit neatly into radio formats while retaining a sense of intimacy. This made her one of the most recognizable voices of the decade, especially across racially mixed audiences. Yet this same accessibility sometimes led critics to underestimate the emotional intelligence of her performances.

For others, radio success came later or remained uneven. Gladys Knight built her audience gradually, relying on touring and word of mouth as much as airplay. Her voice carried warmth and steadiness that resonated deeply, even when chart success lagged behind that of more aggressively promoted artists.

Cultural reach extended beyond charts. Soul records were played in homes, cars, and community spaces. They accompanied everyday life. Female voices became familiar companions, offering reassurance, reflection, and release. This presence mattered as much as numerical success.

Commercial recognition also brought scrutiny. Image, behavior, and personal life became part of public narrative. Success demanded consistency, not only musically but emotionally. Many women carried this pressure quietly, maintaining composure while navigating demanding schedules and expectations.

In this way, commercial success was both achievement and constraint. Female soul legends learned to inhabit it carefully, using visibility to sustain their voices while protecting the emotional truth that made their music resonate in the first place.

As the 1960s drew to a close, the landscape of soul music began to shift. Social movements evolved, musical tastes changed, and the industry itself became more segmented. For female soul singers, this period marked a moment of uncertainty. The voices that had defined the decade were now expected to adapt without losing relevance or authority.

Longevity required flexibility. Some artists leaned into maturity, allowing their voices to deepen and their themes to broaden. Love songs became more reflective. Performances slowed, making room for nuance. This transition was not always welcomed by labels that prioritized youth and immediacy. Yet it allowed certain singers to maintain emotional credibility as their audiences aged alongside them.

Aretha Franklin navigated this shift by expanding her musical range without abandoning her core identity. Her late 1960s and early 1970s recordings reflected confidence and self awareness. She no longer needed to assert authority. It was assumed. This quiet confidence marked a turning point in how female soul artists could age within the industry.

Others faced greater resistance. Etta James encountered fluctuating support from labels as musical trends moved toward funk and psychedelic influences. Her emotional intensity remained undeniable, but industry structures were less forgiving. Reinvention became a matter of survival rather than choice.

For some, the end of the decade brought retreat rather than transformation. Exhaustion, personal struggle, or disillusionment led artists to step back from the spotlight. The demands of constant visibility had taken their toll. Soul music moved forward, but not always with space for the women who had shaped it.

This moment did not mark an ending so much as a threshold. The foundations laid in the 1960s would continue to influence future generations, even as the spotlight shifted. Female soul legends entered the next era carrying both achievement and unanswered questions about how their voices would be valued in a changing musical world.

Labels, Power, and the Soul Industry

Albums and Songs That Defined the Era

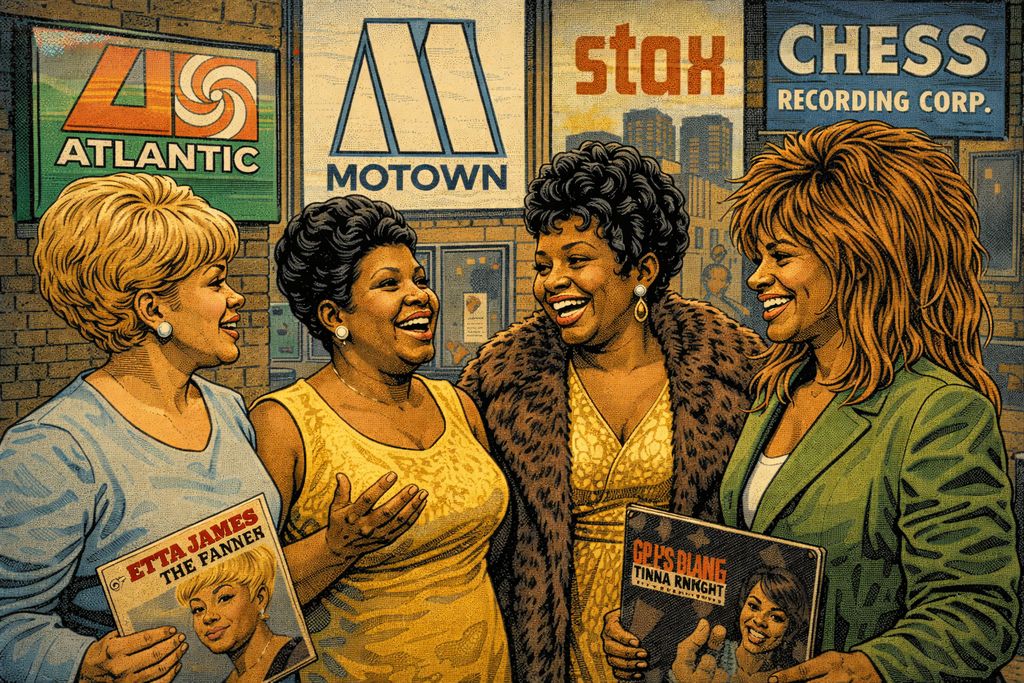

Female soul careers were shaped as much by labels as by voices. In the 1960s, record companies were not neutral platforms. They were power centers that determined sound, image, and longevity. Understanding female soul legends requires understanding the environments in which they recorded.

Atlantic Records positioned itself as a home for emotionally direct, gospel informed soul. The label valued intensity and spontaneity, often allowing singers more expressive freedom in the studio. This approach suited artists whose authority came from emotional presence rather than polish. Atlantic’s success, however, did not always translate into fair treatment. Many female artists later discovered that their commercial impact far exceeded their financial compensation.

Motown Records followed a different philosophy. Motown emphasized refinement, crossover appeal, and consistency. Female singers were carefully styled and tightly produced. The result was mass visibility and global success, but also limited autonomy. Emotional expression was shaped to fit a unified brand. For some artists, this provided stability. For others, it created frustration and constraint.

At Stax Records, the atmosphere was more collaborative. The label’s Southern roots fostered a raw, communal sound. Studio musicians and singers interacted closely, often recording live. Female artists benefited from this immediacy, which allowed emotion to remain central. Yet Stax struggled with distribution and long term financial security, limiting the reach of some careers.

Chess Records bridged blues and soul, offering space for emotional grit and directness. Female singers working with Chess often navigated a male dominated blues tradition, where toughness was valued but vulnerability was less protected.

Each label offered opportunity and risk. None were built to prioritize female autonomy. Yet within these structures, women shaped recordings that outlived the systems that constrained them. Labels controlled access, but voices carried meaning beyond contracts. Understanding these environments helps explain why female soul legends sound the way they do, and why their careers unfolded so unevenly.

Contracts, Royalties and Creative Control

Behind the success of many female soul records lay contracts that offered visibility without security. In the 1950s and 1960s, recording agreements were often short, opaque, and heavily weighted in favor of labels. For women, especially Black women, access to legal counsel was limited. Many signed contracts without full understanding of royalty structures, publishing rights, or long term implications.

Royalties were frequently minimal or delayed. Advances were small and quickly recouped through studio costs, promotion, and touring expenses charged back to the artist. A record could sell well and still leave the singer in debt. This reality was rarely visible to the public, who assumed commercial success equaled financial stability.

Ruth Brown later became one of the most vocal figures addressing these injustices. Despite being a central force behind Atlantic Records’ early success, she received little compensation during her peak years. Her later activism helped bring attention to unfair royalty practices and contributed to industry reforms decades after the fact. Her case illustrates how foundational female contributions were often economically erased.

Creative control was another contested space. Repertoire decisions, song keys, tempos, and arrangements were typically dictated by producers and executives. Female singers were expected to deliver emotionally, not decide structurally. Those who pushed back risked being labeled difficult or uncooperative, labels that could stall careers quickly.

Some artists found ways to negotiate greater influence over time. Success provided leverage, but it rarely translated into full autonomy. Even established singers often had to fight for song choices or insist on trusted collaborators. Control was incremental and fragile.

These contractual realities shaped artistic outcomes. Emotional honesty thrived despite structural limitation, not because of support. Understanding this context is essential to appreciating the resilience behind classic recordings. Female soul legends were not only interpreters of feeling. They were survivors of an industry that profited from their voices while denying them equal ownership of their work.

Why Female Artists Were Marketed Differently

Marketing shaped how female soul artists were seen long before listeners heard their voices. Labels understood that women carried emotional credibility, but they often framed that credibility in restrictive ways. Female artists were marketed as voices of feeling rather than as creative forces. Their authority was emotional, not intellectual or structural.

Visual presentation played a central role. Album covers emphasized elegance, approachability, or glamour, depending on the label’s target audience. Strength was softened. Complexity was simplified. Female soul singers were rarely presented as auteurs. Instead, they were positioned as interpreters of emotion, even when their artistic input shaped the recordings deeply.

This approach affected repertoire choices. Songs assigned to women often focused on love, longing, and heartbreak. These themes were not trivial, but they were framed as personal rather than political. When women expressed anger, confidence, or defiance, those emotions were often reframed as attitude rather than intention. The same qualities celebrated in male artists were treated with caution when voiced by women.

Dionne Warwick was marketed as refined and controlled, a voice suited for sophistication and restraint. This image helped her achieve broad crossover success, but it also narrowed how her emotional range was perceived. Listeners often underestimated the interpretive intelligence behind her performances.

In contrast, artists like Aretha Franklin were framed around power and authenticity, yet even this framing came with limits. Her strength was celebrated as natural rather than cultivated, as if it emerged without intention or craft. This narrative obscured her deep musical knowledge and strategic decision making.

Marketing also shaped public expectation. Once an image was established, deviation was risky. Reinvention could confuse audiences and unsettle labels. Female soul singers learned to navigate these expectations carefully, balancing authenticity with survival.

These marketing strategies did not define the music itself, but they influenced how it was received and remembered. Understanding this context allows us to hear beyond the surface. It reveals how much agency female soul legends exercised within systems designed to contain them.

Producers, Songwriters, and Invisible Architects

Producer-Driven Sound vs. Artist Identity

As soul music became commercially valuable, the balance of power in the studio shifted further toward producers. They controlled budgets, schedules, and access to musicians. Sound was increasingly shaped from the top down. For female soul singers, this environment created a constant tension between personal identity and externally imposed direction.

Producers often approached recordings with a clear template in mind. Successful arrangements were repeated. Vocal styles that sold records were reinforced. Within this system, singers were expected to deliver emotion reliably, not to redefine the framework. Individuality was welcome only when it fit established patterns.

Yet artist identity could not be fully contained. Female soul singers asserted themselves through interpretation rather than overt control. A producer might choose the song, but the singer decided how it felt. Timing, emphasis, and emotional shading became tools of quiet resistance. Identity lived in the spaces between notes.

Aretha Franklin famously navigated this dynamic by reshaping material from the inside. Even when arrangements were set, her phrasing redirected attention. She altered emotional priorities without challenging authority directly. Over time, this approach gave her leverage, allowing greater influence in the studio.

Other artists experienced more rigid producer dominance. Tammi Terrell worked within tightly controlled Motown systems where sound and image were standardized. Her voice carried warmth and clarity, but opportunities to assert individual identity were limited. Her work reveals both the strength of her presence and the constraints she faced.

Producer driven sound was not inherently negative. Skilled producers could elevate recordings, providing structure and clarity. Problems arose when this structure left no room for growth. For women, pushing against these limits often came at a cost.

This tension shaped the sound of classic soul. The most enduring recordings reflect moments where artist identity pierced through producer control. Listening closely, one can hear not only the song, but the negotiation behind it. That negotiation is part of what gives female soul performances their lasting emotional depth.

Songwriting Credit, Ownership and Dependency

Songwriting credit was one of the most unevenly distributed forms of power in the soul industry. Many female soul singers built their careers on songs they did not write, and often were not encouraged to write. This was not always due to lack of ability. It was the result of industry assumptions about authorship and authority.

Publishing rights generated long term income and control. By keeping songwriting in the hands of in house teams or male collaborators, labels secured ownership while positioning singers as vessels for expression rather than creators. Dependency was built into the system. A singer relied on producers and writers not only for material, but for access to the studio itself.

This structure shaped artistic confidence. Even singers with strong musical instincts were taught to defer. Suggestions could be framed as interference. Curiosity could be read as challenge. Over time, many women internalized the idea that their role was to interpret, not to originate. This limitation was rarely acknowledged publicly, but it affected career trajectories deeply.

Nina Simone was a notable exception. Trained as a classical pianist, she wrote and arranged much of her material. Her insistence on ownership and authorship placed her at odds with labels and promoters. While this limited her commercial reach, it preserved her autonomy. Her case highlights what was possible, and what it cost.

Others navigated dependency more quietly. Etta James contributed significantly to the emotional shape of her recordings, even when her name did not appear in writing credits. Her influence lived in phrasing, tone, and delivery, elements that could not be easily quantified or owned, but were central to the song’s impact.

Lack of ownership affected longevity. When trends shifted, singers without publishing control were more vulnerable. Their voices had built catalogs they did not fully possess. This imbalance continues to shape how female soul legacies are valued today. Understanding authorship reveals not only who created the music, but who benefited from it.

When Collaboration Became Control

Collaboration was often presented as a gift. Producers, arrangers, and songwriters framed their involvement as support, guidance, or expertise. For many female soul singers, collaboration did begin this way. It offered access to studios, musicians, and distribution networks that were otherwise closed to them. Over time, however, collaboration frequently shifted into control.

This shift was subtle. Decisions were made in the name of efficiency or market logic. A suggestion about tempo became a rule. A preferred arrangement became non negotiable. Emotional instincts were questioned if they conflicted with commercial expectations. Because these changes happened gradually, resistance was difficult to articulate. What was lost rarely disappeared all at once.

Female singers were often encouraged to trust the process. Deference was framed as professionalism. Assertiveness could be interpreted as instability or ego. In this environment, collaboration became a test of compliance. Those who adapted were rewarded with continued work. Those who pushed back risked being sidelined.

The cost of this imbalance was not always visible in the recordings themselves. Many classic soul songs remain powerful precisely because singers poured everything they had into them. Yet behind the scenes, the emotional labor was uneven. Women were expected to give fully without equivalent say in direction or ownership.

Tammi Terrell illustrates this dynamic painfully. Her collaborative work produced enduring recordings, but her role within the system left little space for agency. The music endures, yet the conditions under which it was made reveal how fragile collaboration could become when power was not shared.

Some artists learned to navigate this terrain by choosing their collaborators carefully. Aretha Franklin gradually surrounded herself with musicians who responded to her leadership rather than directing it. In those moments, collaboration returned to its original promise. It became mutual rather than managerial.

Understanding when collaboration crossed into control helps explain both the brilliance and the strain within female soul catalogs. These voices carry not only emotion, but negotiation. Listening closely, one can hear moments of freedom and moments of constraint existing side by side. That tension is part of the history we hear, even when it is not named.

Fame, Exploitation, and Personal Struggle

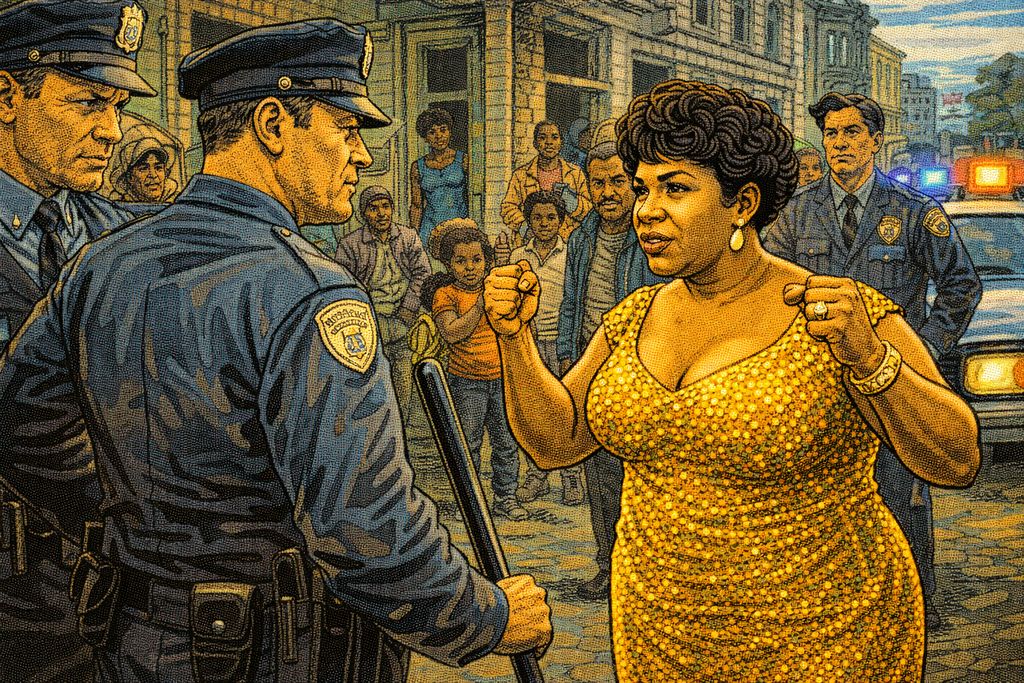

Gender, Racism and Industry Politics

For female soul singers, success unfolded within an industry shaped by both gender bias and systemic racism. These forces did not operate separately. They reinforced each other, limiting access to resources, shaping public narratives, and narrowing the space in which women could act freely. Talent opened doors, but it did not dismantle structures.

Race determined market segmentation. Black female artists were often confined to so called race records or soul categories, even when their music reached broad audiences. Crossover success was welcomed financially, but not always culturally. Artists were praised for appeal while still being excluded from decision making spaces. Visibility did not equal influence.

Gender compounded these barriers. Women were expected to be reliable, emotionally available, and adaptable. Assertiveness was frequently reframed as temperament. Disagreement could be labeled ungratefulness. These perceptions affected touring schedules, studio access, and promotional support. A woman who challenged authority risked being seen as a liability rather than a professional.

Industry politics further complicated matters. Labels competed for market share, radio stations guarded playlists, and promoters prioritized predictability. In this environment, female soul singers were often positioned as representatives rather than individuals. Their behavior was expected to reflect not only on themselves, but on entire genres or communities. This burden was rarely placed on male counterparts.

Artists like Nina Simone experienced direct consequences when refusing to soften political expression. Her willingness to confront injustice openly affected bookings and airplay. Others navigated politics more quietly, choosing strategic restraint to preserve access and longevity.

Gender and race shaped not only opportunity, but narrative. Media coverage often emphasized personal life over artistic process. Success was framed as exceptional rather than earned. Failure was personalized rather than contextualized.

Understanding these dynamics is essential to hearing female soul music clearly. The emotion in these recordings carries more than personal feeling. It carries the weight of navigating an industry that demanded brilliance while withholding equity. That tension is embedded in the sound itself.

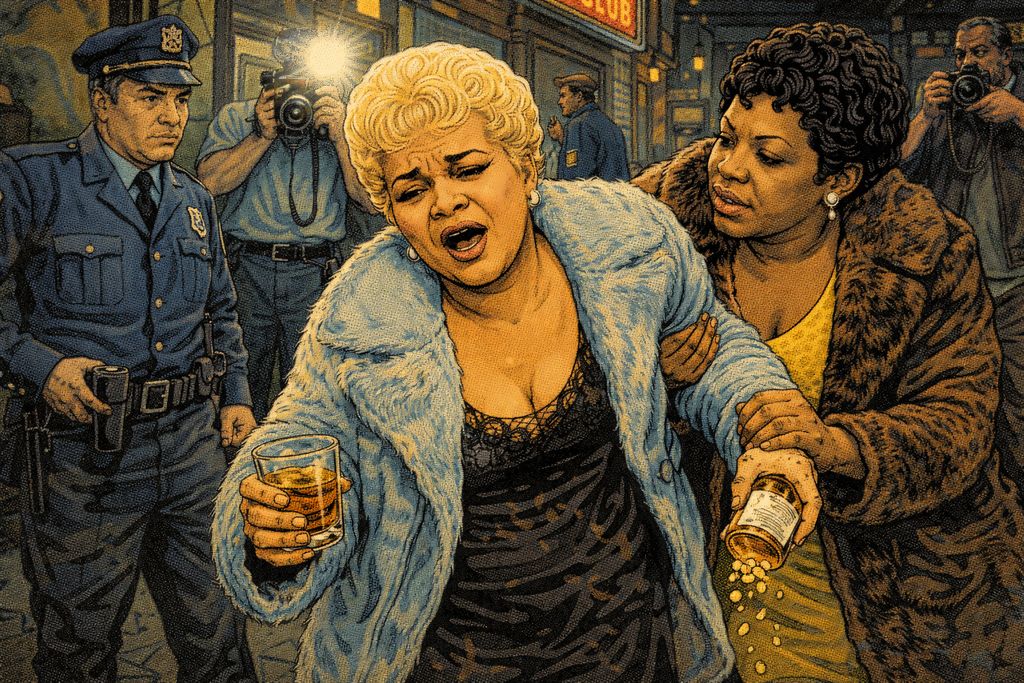

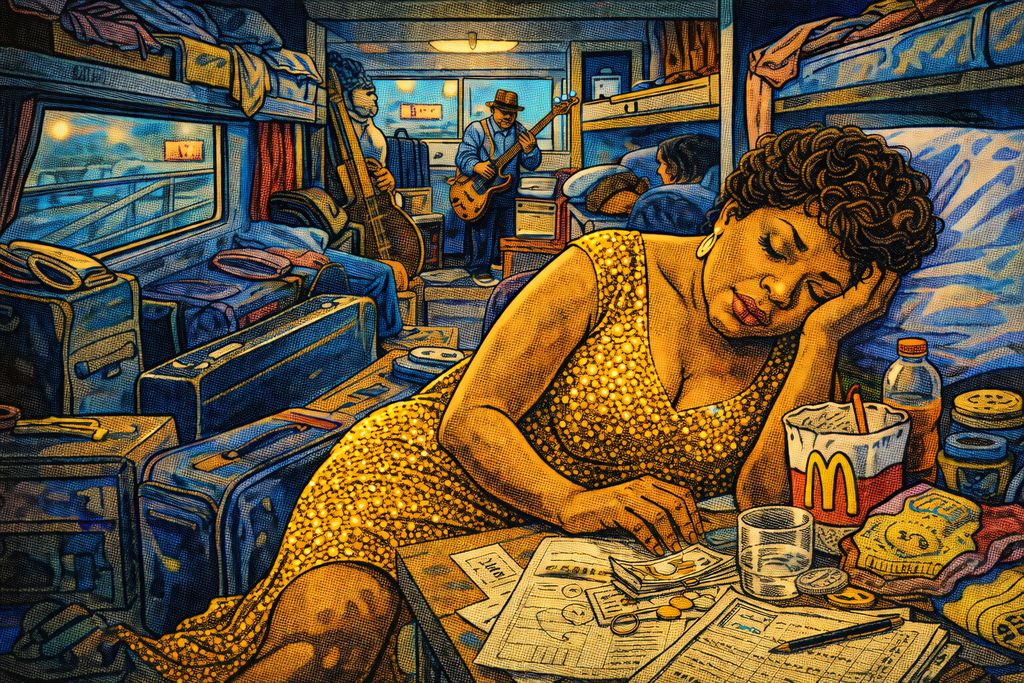

Mental Health, Addiction and Public Breakdown

The emotional intensity that gave soul music its power also carried personal cost. Female soul singers were expected to access deep feeling repeatedly, often without adequate support or protection. The industry celebrated emotional openness on record, but rarely provided space for recovery offstage. Mental health was not discussed openly. Struggle was hidden until it became visible.

Touring schedules were demanding, privacy was limited, and expectations were relentless. Women were asked to remain composed regardless of exhaustion, grief, or illness. When cracks appeared, they were often framed as personal weakness rather than as the result of sustained pressure. Emotional labor was treated as an endless resource.

Addiction became one way some artists coped. Substances offered temporary relief from anxiety, physical pain, and emotional overload. They also intensified instability. The public narrative often reduced these struggles to scandal, overlooking the structural conditions that contributed to them.

Etta James faced periods of severe addiction that disrupted her career and damaged her health. Her voice remained extraordinary, but support systems were inconsistent. Rather than addressing underlying causes, the industry often withdrew when reliability became uncertain. Her story reflects a broader pattern in which vulnerability was punished rather than understood.

Mental health challenges also emerged in less visible ways. Anxiety, depression, and emotional burnout were common but rarely named. Artists continued to perform, even as the weight of expectation grew heavier. Silence became a form of survival.

When breakdowns occurred publicly, media coverage was unforgiving. Struggle was sensationalized. Context was ignored. Recovery, when it happened, was rarely celebrated with the same intensity as decline. This imbalance shaped public memory, often overshadowing artistic achievement.

Understanding mental health within female soul history requires listening beyond headlines. These women did not lack resilience. They were often asked to carry more than any individual should. Their music remains powerful not because it emerged from suffering, but because it transformed experience into sound with honesty and courage.

Media Narratives and the Cost of Visibility

Visibility was a double edged reality for female soul singers. Public recognition brought opportunity, but it also invited constant interpretation. Media narratives rarely focused on process or craft. Instead, they emphasized personality, appearance, and perceived temperament. Artistic work became secondary to image.

Coverage often reduced complex careers to simplified stories. A singer was framed as gifted but difficult, powerful but unstable, emotional but unreliable. These labels stuck easily and were hard to shake. Once a narrative took hold, it shaped how performances were received. Strength could be read as arrogance. Vulnerability could be framed as weakness.

Women were also expected to represent more than themselves. Their behavior was often treated as symbolic, reflecting on communities, genres, or movements. This burden intensified scrutiny. A misstep carried broader consequences. Mistakes were not isolated. They were generalized.

Aretha Franklin experienced this tension throughout her career. Her authority and success made her a public figure beyond music. Interviews, appearances, and personal decisions were dissected for meaning. While she maintained control over her artistic output, public narratives frequently ignored her strategic intelligence, favoring simplified ideas of natural genius or temperament.

Media attention also affected longevity. As artists aged, coverage shifted. Younger voices were celebrated as fresh, while established singers were framed as past their peak. This transition was often abrupt. The same media that once amplified their voices now questioned their relevance.

The cost of this visibility was cumulative. Constant observation limited space for growth, error, or reinvention. Privacy became scarce. Silence was interpreted as decline. Presence was required even when it was unsustainable.

Understanding these narratives helps explain why some careers appear fragmented or uneven on the surface. The music tells one story. The media often tells another. Listening closely means resisting simplified versions of these lives. Female soul legends carried their voices into public view knowing the risk. Their willingness to remain present, despite distortion, is part of their legacy.

Female Soul Beyond the United States

The Global Spread of Soul

Soul music did not remain confined to the United States. As recordings traveled, radio signals crossed borders, and touring circuits expanded, the emotional language of soul began to resonate internationally. Female voices played a crucial role in this spread. Their ability to communicate feeling across linguistic and cultural boundaries made soul accessible far beyond its original social context.

In Europe, soul arrived through records, television appearances, and live tours. Audiences responded not because they shared the same historical experience, but because the emotional clarity felt immediate. The themes of dignity, longing, and resilience translated easily. Female singers became ambassadors of feeling rather than representatives of a specific place.

Artists such as Shirley Bassey illustrate this dynamic. Though rooted in a British context, her vocal delivery carried the weight and intensity associated with American soul. Her phrasing drew on gospel and blues traditions while adapting them to orchestral arrangements favored by European audiences. This hybrid approach expanded the definition of soul without diluting its emotional core.

Beyond Europe, soul connected with regions shaped by colonial histories and social struggle. In Africa and the Caribbean, listeners recognized familiar emotional patterns. Songs about injustice, hope, and survival resonated deeply. Soul became a shared emotional vocabulary, even when musical traditions differed.

Miriam Makeba represents this global exchange powerfully. While often associated with African folk traditions, her phrasing and emotional delivery aligned closely with soul sensibilities. Exile shaped her career, positioning her voice within an international network of listeners who understood music as both expression and testimony.

The global spread of soul did not erase its origins. Instead, it revealed how specific experiences could generate universal resonance. Female soul singers carried emotion with clarity and restraint, allowing listeners to locate themselves within the sound. This ability to travel emotionally without losing grounding is one of the reasons soul became a truly international language.

Local Traditions and Cultural Translation

As soul music moved across borders, it did not remain unchanged. Local traditions shaped how it was received, interpreted, and re expressed. Female singers outside the United States did not simply imitate American models. They adapted soul’s emotional framework to their own cultural realities, creating new hybrids that felt authentic rather than derivative.

In the United Kingdom, soul merged with orchestral pop, jazz phrasing, and theatrical delivery. This approach emphasized clarity and dramatic control. Emotional intensity was present, but it was framed through restraint and precision. Singers learned to balance power with articulation, ensuring that feeling remained intelligible to audiences unfamiliar with gospel traditions.

Shirley Bassey again serves as a clear example. Her performances drew on the emotional authority of soul while incorporating European notions of stagecraft. The result was a voice that commanded space without relying on improvisation. Emotion was structured, shaped, and sustained, demonstrating that soul could thrive within different aesthetic systems.

In Africa, soul intersected with local rhythms, languages, and political realities. Vocal delivery often emphasized collective experience rather than individual confession. Call and response patterns resonated strongly, reflecting communal traditions already in place. Soul’s emotional honesty aligned naturally with music used for storytelling and resistance.

Miriam Makeba translated soul’s expressive depth into a global language of exile and identity. Her performances carried dignity and restraint, allowing emotion to emerge without spectacle. Though her repertoire differed from American soul catalogs, her vocal presence shared the same core values of truth and connection.

Cultural translation also involved limitation. In some regions, racial dynamics differed, altering how Black female voices were perceived. Access to industry infrastructure varied widely. Recognition abroad did not always translate into sustained support at home.

These adaptations reveal soul not as a fixed style, but as a method of emotional communication. Female singers across cultures understood its essence and reshaped it to fit their realities. In doing so, they expanded the genre’s reach while preserving its integrity.

International Success vs. Home-Country Marginalization

International recognition did not always lead to security or acceptance at home. For many female soul singers, success abroad contrasted sharply with marginalization in their country of origin. Touring internationally offered larger audiences, better working conditions, and in some cases greater respect. Yet this distance could also deepen feelings of disconnection.

In Europe and other regions, soul artists were often received as cultural figures rather than genre performers. Audiences engaged with the emotional depth of the music without imposing rigid expectations. This openness allowed singers to experiment, mature, and sustain longer careers. Financial stability abroad sometimes exceeded what was possible at home.

At home, however, industry dynamics remained unchanged. Labels continued to prioritize younger artists and emerging trends. Media attention shifted quickly. Success abroad could even be framed as evidence of decline, suggesting that an artist was no longer relevant domestically. This narrative ignored structural limitations and reduced complex careers to simplistic arcs.

Miriam Makeba experienced this tension acutely. Exile brought international acclaim but limited her ability to maintain a stable home base. Political circumstances shaped where she could perform and record. While celebrated globally, she faced restrictions that affected her long term career planning.

Other artists found themselves sustaining their work primarily through international touring. While this offered continuity, it also created exhaustion. Distance from home meant limited support networks. Cultural translation required constant adaptation. The emotional labor of performing identity abroad added to existing pressures.

This imbalance reveals a broader pattern. Female soul singers often carried their strongest recognition outside the systems that first shaped them. Their voices traveled more freely than their professional security. International success provided validation, but it did not dismantle the structural inequities waiting at home.

Understanding this dynamic challenges simplistic narratives of success. It reminds us that visibility is not the same as stability. Female soul legends navigated global admiration while managing ongoing marginalization. Their endurance under these conditions adds depth to their achievements and complicates how their legacies are understood.

Soul, Womanhood, and Public Image

Respectability, Body Image and Gender Expectations

Respectability shaped the public lives of female soul singers as much as their music did. From the beginning of their careers, women were expected to embody dignity, control, and restraint. This expectation was not only personal, it was cultural. Black female artists in particular were burdened with representing morality, stability, and emotional balance in a society eager to police their visibility.

Body image became part of this scrutiny. Appearance was framed as evidence of character. Weight, clothing, posture, and facial expression were interpreted as signals of discipline or excess. Female soul singers learned quickly that their bodies would be read alongside their voices. A powerful performance could be undermined by commentary on looks. Emotional intensity could be reframed as lack of control.

These expectations were unevenly applied. Male artists were allowed eccentricity, volatility, and visible aging. Women were expected to remain composed, attractive, and emotionally available at all times. Deviation invited criticism. Compliance demanded constant self monitoring.

Artists navigated this terrain carefully. Aretha Franklin maintained an image that combined authority and elegance. Her presence communicated strength without confrontation. This balance was not accidental. It reflected an acute awareness of how quickly admiration could turn into judgment. Her visual self presentation supported her vocal authority rather than distracting from it.

Respectability politics also shaped lyrical interpretation. Songs about desire or pain were delivered with restraint, allowing emotion to surface without violating public expectation. This control did not weaken expression. It sharpened it. Listeners sensed the effort behind the composure.

The cost of these expectations was cumulative. Constant regulation of appearance and behavior left little room for rest or experimentation. Yet many female soul singers transformed constraint into clarity. By mastering the codes imposed on them, they preserved space for emotional truth within narrow margins.

Understanding respectability and body politics helps explain why female soul performances often feel measured rather than explosive. The restraint is not absence of feeling. It is evidence of awareness, survival, and deliberate presence within a world that demanded far more from women than from their male peers.

Sexuality, Strength and Public Morality

Sexuality was a charged subject for female soul singers, shaped by contradiction. Desire sold records, but open expression invited judgment. Strength attracted admiration, but confidence risked being labeled improper. Within this narrow corridor, women learned to signal sexuality without surrendering control over how it was read.

Public morality imposed uneven rules. Expressions of longing or independence that were celebrated in male artists were scrutinized when voiced by women. A suggestive lyric could be framed as transgression. A confident stance could be interpreted as provocation. Female soul singers responded by developing coded forms of expression. Tone, timing, and phrasing carried meaning where words could not.

Etta James navigated this tension with raw honesty. Her performances acknowledged desire and vulnerability openly, refusing to soften emotion for comfort. This honesty made her voice compelling, but it also exposed her to moral judgment that followed her throughout her career. Strength and sexuality were inseparable in her work, a combination that challenged conventional expectations.

Others chose a more restrained path. Aretha Franklin expressed sexuality through confidence rather than display. Her delivery suggested autonomy and self knowledge. Desire was framed as mutual respect rather than pursuit. This approach allowed her to maintain authority while engaging deeply with themes of intimacy.

Public morality also affected career longevity. Women who were perceived as too sexual risked reduced radio play or limited promotional support. Those who appeared too reserved risked being dismissed as distant. Balancing these perceptions required constant adjustment.

The result was a layered emotional language. Sexuality was present, but rarely explicit. Strength was communicated through steadiness rather than confrontation. Female soul singers did not deny desire. They shaped it carefully, embedding it within broader expressions of dignity and control.

Understanding this dynamic reveals how much intention lay behind classic performances. These voices carried not only feeling, but awareness. They navigated moral scrutiny while preserving emotional truth, turning constraint into nuance. That nuance remains one of soul music’s most enduring qualities.

Fashion, Hair and Visual Self-Definition

Visual self presentation was never separate from music for female soul singers. Clothing, hair, and posture became extensions of vocal identity, especially in an era when images circulated through album covers, television appearances, and press photography. These visual choices were not simply aesthetic. They were negotiations with expectation.

Fashion offered both limitation and possibility. Labels often favored looks that felt safe and marketable. Elegance, restraint, and polish were encouraged. Individual expression was allowed only within narrow boundaries. Female soul singers learned to work inside these limits, using detail rather than spectacle to assert identity.

Hair carried particular significance. Natural styles, straightened looks, and wigs were all read politically and socially. A hairstyle could signal respectability, rebellion, or adaptability. These readings were imposed as much as they were chosen. Women were aware that their hair would be interpreted alongside their voices, shaping how audiences perceived authenticity and control.

Aretha Franklin understood this dynamic deeply. Her visual presence balanced authority and accessibility. Whether dressed formally or more relaxed, she projected intention. Nothing felt accidental. Her image supported the idea that power could coexist with grace, and that strength did not require confrontation.

Other artists used fashion to challenge expectations more directly. Nina Simone often rejected conventional glamour, choosing simplicity or severity. Her appearance reinforced the seriousness of her message. It communicated focus rather than seduction, intellect rather than decoration. This choice limited her mainstream appeal, but it preserved alignment between her music and her values.

Visual self definition also evolved over time. As artists aged, expectations shifted. Maintaining relevance meant adapting appearance without erasing identity. This balancing act required constant awareness.

Fashion and hair were never distractions from the music. They were part of the same conversation. Female soul singers used visual language to frame how their voices were received, protecting emotional truth while navigating a world eager to reduce complexity. In doing so, they turned appearance into another form of authorship.

Overlooked, Regional and Forgotten Voices

One-Album Careers and Lost Catalogues

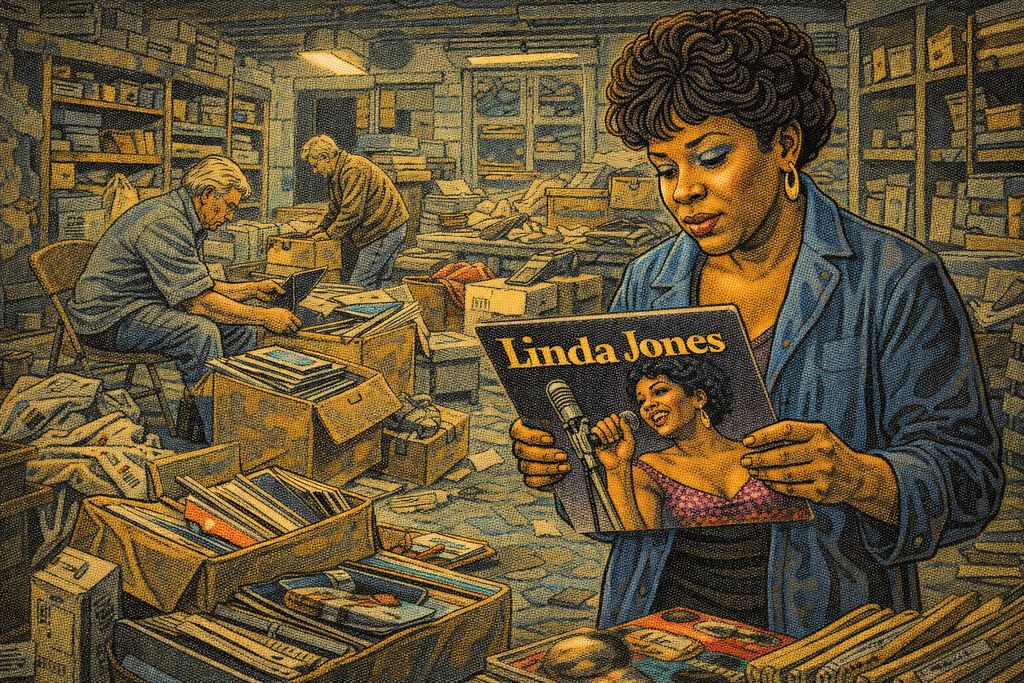

Not every influential voice left behind a large catalogue. Some female soul singers recorded a single album, a handful of singles, or material that never received proper distribution. Their limited output was not always the result of artistic choice. More often, it reflected fragile industry support, financial strain, or sudden shifts in label priorities.

One album careers were common in an era when labels moved quickly and invested cautiously. If early sales disappointed or trends shifted, support vanished. Promotion stopped. Touring opportunities dried up. For women, especially those without strong managerial backing, a stalled debut could quietly end a recording career. Talent alone was not enough to secure longevity.

Lost catalogues present another challenge. Masters were sometimes shelved, misplaced, or absorbed into label mergers. Artists who recorded regionally or for smaller imprints were particularly vulnerable. Their work circulated locally, built loyal audiences, and then disappeared from view. Decades later, these recordings resurface through reissues or archival projects, revealing voices that once shaped scenes but were never canonized.

The emotional cost of these interruptions was significant. Recording an album required vulnerability, time, and trust. When support vanished, many singers returned to other forms of work, carrying unresolved artistic identities. Their voices lived on in memory rather than in sustained careers.

These limited discographies complicate how we measure impact. Influence is often equated with volume. In soul music, this equation fails. A single recording can carry profound weight, shaping listeners and fellow musicians alike. The absence of a long catalogue does not imply absence of contribution.

Recognizing one album careers requires a shift in perspective. It means valuing presence over accumulation. It means listening closely to what exists rather than lamenting what does not. Female soul history includes many such voices, brief in documentation but rich in feeling. Their stories remind us that endurance in music is not only about survival. It is also about moments that mattered deeply, even if they did not last.

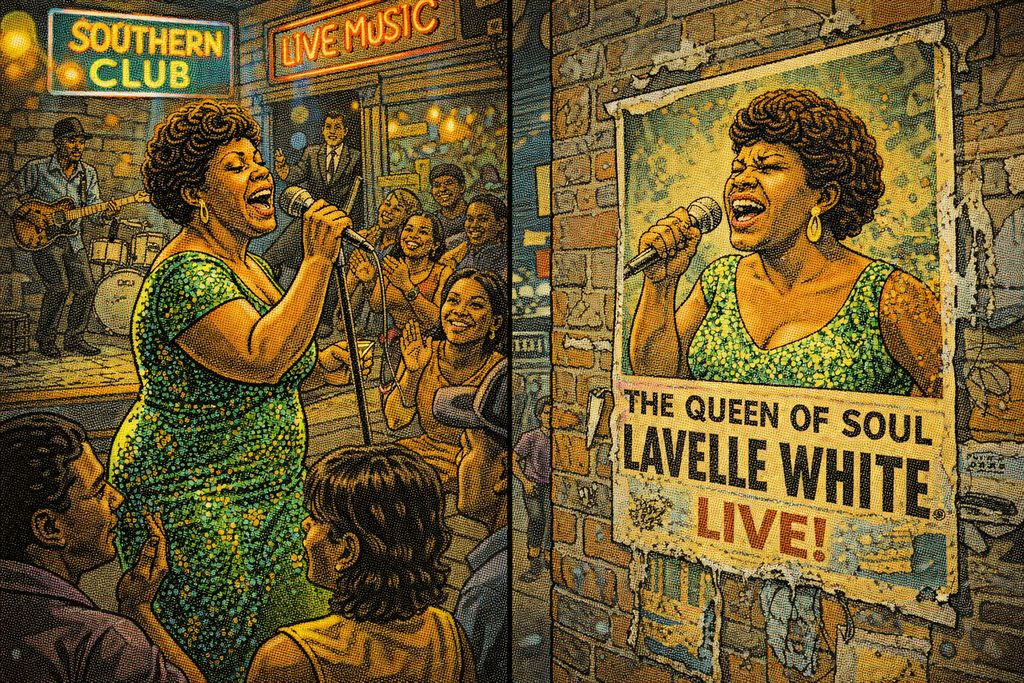

Regional Queens Without Global Recognition

Not all female soul influence traveled nationally or internationally. In many cities and regions, singers became central figures without ever crossing into mainstream visibility. These women filled clubs, theaters, churches, and local radio playlists. Their names carried weight within specific communities, even if they never appeared on national charts.

Regional scenes offered both opportunity and limitation. On one hand, they allowed singers to develop strong connections with audiences who recognized their voices as part of shared local identity. On the other, they lacked the infrastructure needed to scale careers. Distribution was limited. Touring networks were fragmented. Media coverage rarely extended beyond city boundaries.

These artists often balanced music with other work, performing on weekends or rotating through local venues. Their professionalism was undeniable. They rehearsed, refined their sound, and built reputations based on consistency rather than hype. In many cases, their influence shaped younger musicians who later reached wider audiences.

The absence of global recognition does not indicate lesser artistry. It reflects how uneven access to resources shaped musical history. Regional queens were often excluded from national narratives because they lacked label backing, not because they lacked vision or skill. Their contributions were absorbed into the fabric of local culture rather than documented in archives.

Some recordings exist only as rare singles, radio sessions, or privately pressed albums. Others survive through oral history and memory. Listeners remember where they first heard these voices, how the room felt, how the music resonated. This form of legacy is intimate and fragile. It resists easy documentation.

Recognizing regional soul queens requires widening the lens. It means valuing influence that does not translate into sales figures. It means acknowledging that soul music thrived in countless local ecosystems, sustained by women whose dedication kept scenes alive.

Their stories challenge simplified histories built around stars and charts. They remind us that soul was not only shaped in major studios or broadcast nationally. It was nurtured night after night in smaller rooms, carried by voices that mattered deeply where they were heard. These women may not be globally famous, but their impact remains embedded in the communities they served.

Session Singers and Uncredited Contributors

Behind many well known soul recordings stand voices that were never credited on album covers. Session singers, background vocalists, and informal contributors shaped harmonies, textures, and emotional depth without receiving public recognition. Their work was essential, yet their names rarely entered the historical record.

Session singing required versatility and restraint. These women had to adapt quickly, blend seamlessly, and support lead performances without drawing attention away from them. Their voices carried emotional weight while remaining deliberately anonymous. This invisibility was often framed as professionalism, but it also reflected structural inequality. Credit and authorship remained concentrated at the top.

Many session singers were highly trained, often coming from the same church and choir backgrounds as lead artists. They understood phrasing, harmony, and emotional pacing instinctively. In the studio, they worked under tight schedules, expected to deliver flawless performances in few takes. Their contribution could elevate a recording dramatically, yet it was absorbed into the overall sound rather than acknowledged individually.

Lack of credit affected long term opportunity. Without visible discographies, session singers struggled to leverage their work into solo careers. Even when their voices were recognizable, the absence of formal recognition limited bargaining power. They remained essential but replaceable in the eyes of the industry.

Some singers preferred this role, valuing stability over visibility. Others accepted it as the only available path into professional music. In both cases, their labor sustained the genre. The richness of classic soul owes much to these layered voices, often female, often Black, often uncredited.

Recognizing session singers requires listening differently. It means hearing not just the lead line, but the emotional architecture beneath it. Harmonies that rise and fall, responses that echo, textures that deepen feeling. These elements did not appear by accident. They were created by skilled singers whose work deserves acknowledgment.

Including these contributors expands our understanding of female soul history. It reveals how collective the genre truly was, and how many women shaped its sound without receiving public acclaim. Their absence from headlines does not diminish their presence in the music itself.

Life on the Road - Touring as a Female Soul Artist

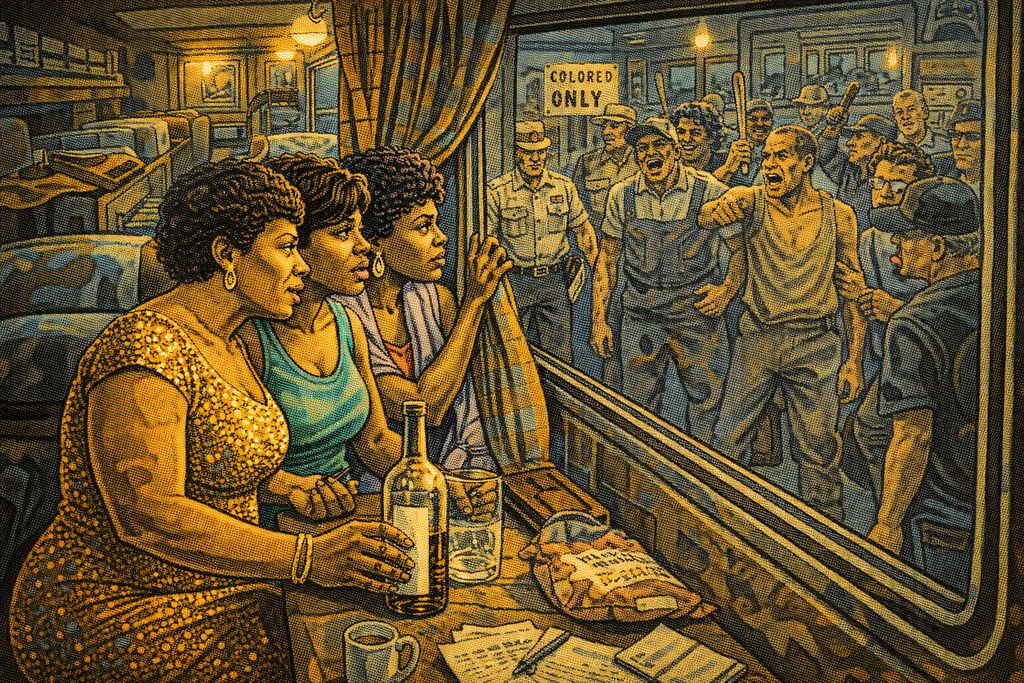

Segregation, Safety and Survival

Touring was central to sustaining a soul career, but for female singers it came with significant risk. In the 1950s and 1960s, travel routes were shaped by segregation laws, informal discrimination, and uneven protection. Venues welcomed Black performers onstage while denying them safety offstage. For women, these conditions were intensified by gendered vulnerability.

Segregation affected every aspect of life on the road. Hotels, restaurants, and rest stops were often inaccessible. Female soul singers traveled long distances without knowing where they would be allowed to sleep or eat. Nights were spent on buses or in private homes arranged through informal networks. These conditions demanded resilience and constant vigilance.

Safety was a daily concern. Touring schedules were exhausting, and isolation increased risk. Women faced harassment from audiences, promoters, and even colleagues. Protection was inconsistent. Speaking up could jeopardize bookings. Silence became a strategy for survival rather than consent.

Despite these challenges, performances continued. Audiences rarely saw the strain behind the music. Onstage, singers were expected to radiate warmth and control, masking exhaustion and fear. Emotional availability was part of the job, even when personal safety felt uncertain.

Artists like Gladys Knight navigated this reality early in their careers, touring extensively while still very young. Support systems were often improvised, relying on family members or trusted musicians. This community offered protection, but it also limited independence.

Touring under segregation required adaptability. Routes were planned carefully. Performances were spaced to allow recovery. Trust became currency. Those who survived developed acute awareness of environment and risk.